"Blues in the Night" Written by Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Dear Friends, in Keeping with the Nostalgic Themes with Which We

Dear friends, In keeping with the nostalgic themes with which we normally open these Activity Pages, I thought I’d tell you a story about young love – its excitement, its promise, and its almost inevitable woes. It’s a true story, one from my own past. And it begins at Roller City, a roller skating rink located, in those distant days, on Alameda Avenue just west of Federal Boulevard in Denver, Colorado. It was a balmy Friday night when I first spied my Cinderella – a lovely, lithe thing with a cute smile, pink ribbons in her blonde hair, and very “girly” bons bons of matching color hanging on the front of her white roller skates. It might have been love at first sight but certainly by the time we skated hand in hand under the multi-colored lights in a romantic “couples skate,” I was a goner. Indeed, I fell more madly in love than I had at any other time in my whole life. I was 10 years old. I drop in that fact because it proved to be the relevant point in the impending tragedy of unrequited love. For you see, it turned out there was an unbridgeable gap in our ages. I was just getting ready to go into the 4th grade whereas I learned she was going into the 5th grade! Yipes! I had fallen for an older woman! How could I break it to her? And how would I deal with the rejection I knew must follow? I was in a terrible jam and so…and I’m not proud of it…I made up a lie. -

Mixed Folios

mixed folios 447 The Anthology Series – 581 Folk 489 Piano Chord Gold Editions 473 40 Sheet Music Songbooks 757 Ashley Publications Bestsellers 514 Piano Play-Along Series 510 Audition Song Series 444 Freddie the Frog 660 Pop/Rock 540 Beginning Piano Series 544 Gold Series 501 Pro Vocal® Series 448 The Best Ever Series 474 Grammy Awards 490 Reader’s Digest Piano 756 Big Band/Swing Songbooks 446 Recorder Fun! 453 The Big Books of Music 475 Great Songs Series 698 Rhythm & Blues/Soul 526 Blues 445 Halloween 491 Rock Band Camp 528 Blues Play-Along 446 Harmonica Fun! 701 Sacred, Christian & 385 Broadway Mixed Folios 547 I Can Play That! Inspirational 380 Broadway Vocal 586 International/ 534 Schirmer Performance Selections Multicultural Editions 383 Broadway Vocal Scores 477 It’s Easy to Play 569 Score & Sound Masterworks 457 Budget Books 598 Jazz 744 Seasons of Praise 569 CD Sheet Music 609 Jazz Piano Solos Series ® 745 Singalong & Novelty 460 Cheat Sheets 613 Jazz Play-Along Series 513 Sing in the Barbershop 432 Children’s Publications 623 Jewish Quartet 478 The Joy of Series 703 Christian Musician ® 512 Sing with the Choir 530 Classical Collections 521 Keyboard Play-Along Series 352 Songwriter Collections 548 Classical Play-Along 432 Kidsongs Sing-Alongs 746 Standards 541 Classics to Moderns 639 Latin 492 10 For $10 Sheet Music 542 Concert Performer 482 Legendary Series 493 The Ultimate Series 570 Country 483 The Library of… 495 The Ultimate Song 577 Country Music Pages Hall of Fame 643 Love & Wedding 496 Value Songbooks 579 Cowboy Songs -

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop for Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop For Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media Author: Steve Roby Showdate : Feb. 18, 2015 Performance Venue : Yoshi’s Oakland Bay Area legend Dan Hicks performed to a sold-out crowd at Yoshi’s on Wednesday. The audience was made up of his loyal fans (Hicksters) who probably first heard his music on KSAN, Jive 95, back in 1969. At age 11, Hicks started out as a drummer, and was heavily influenced by jazz and Dixieland music, often playing dances at the VFW. During the folk revival of the ‘60s, he picked up a guitar, and would go to hootenannies while attending San Francisco State. Hicks began writing songs, an eclectic mix of Western swing, folk, jazz, and blues, and eventually formed Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. His offbeat humor filtered its way into his stage act. Today, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, Hicks sums up his special genre as “Caucasian hip-hop.” Over four decades later, Hicks still delivers a unique performance, and Wednesday’s show was jammed with many great moments. One of the evenings highlights was the classic “I Scare Myself,” which Hicks is still unclear if it’s a love song when he wrote it back in 1969. “I was either in love, or I’d just eaten a big hashish brownie,” recalled Hicks. Adding to the song’s paranoia theme, back-up singers Daria and Roberta Donnay dawned dark shades while Benito Cortez played a chilling violin solo complete with creepy horror movie sound effects. -

RADIO ROCKWAY Odalys Cordero

RADIO ROCKWAY Odalys Cordero Preface It is with great pleasure that I share a Johnny Mercer inspired unit entitled: “Radio Rockway.” This unit utilizes interdisciplinary instruction within a musical setting. The target student audience throughout the curriculum is the 5th grade student population but can easily be adapted to middle and high school level students. The unit is typically completed in approximately nine weeks if music class is taught one hour a week. This unit is designed to educate students on the history and elements of Latin Jazz while simultaneously establishing a creative environment for student to create their own lyrics. On a personal note, I enjoyed witnessing the musical growth in each 5th grade class as they used the framework of pre-existing Latin Jazz songs and lyrically “made it their own,” so to speak. This was a great opportunity for Spanish speakers at an ESOL Level of 1 & 2 level to express themselves more freely throughout the progression of the unit. Overall Organization of Unit UNIT COVER PAGE Unit Title: “Radio Rockway” Grade Level: 5th Grade Subject/Topic Area(s): Studying a selected musical genre typically played on the radio: Latin Jazz. Designed By: Odalys Cordero , Florida International University Unit Duration: 9 Weeks Brief Summary of Unit (Including curricular context and unit goals): Three classes of 5th grade students will learn about the genre of Latin Jazz. This unit will be based on experiencing and creating lyrics to this particular genre. Each class will take on the role of a radio station with the assigned genre. Through these radio stations, students will perform their composition lyrics. -

Rhythm & Blues Rhythm & Blues S E U L B & M H T Y

64 RHYTHM & BLUES RHYTHM & BLUES ARTHUR ALEXANDER JESSE BELVIN THE MONU MENT YEARS CD CHD 805 € 17.75 GUESS WHO? THE RCA VICTOR (Baby) For You- The Other Woman (In My Life)- Stay By Me- Me And RECORD INGS (2-CD) CD CH2 1020 € 23.25 Mine- Show Me The Road- Turn Around (And Try Me)- Baby This CD-1:- Secret Love- Love Is Here To Stay- Ol’Man River- Now You Baby That- Baby I Love You- In My Sorrow- I Want To Marry You- In Know- Zing! Went The My Baby’s Eyes- Love’s Where Life Begins- Miles And Miles From Strings Of My Heart- Home- You Don’t Love Me (You Don’t Care)- I Need You Baby- Guess Who- Witch craft- We’re Gonna Hate Ourselves In The Morn ing- Spanish Harlem- My Funny Valen tine- Concerte Jungle- Talk ing Care Of A Woman- Set Me Free- Bye Bye Funny- Take Me Back To Love- Another Time, Another Place- Cry Like A Baby- Glory Road- The Island- (I’m Afraid) The Call Me Honey- The Migrant- Lover Please- In The Middle Of It All Masquer ade Is Over- · (1965-72 ‘Monument’) (77:39/28) In den Jahren 1965-72 Alright, Okay, You Win- entstandene Aufnahmen in seinem eigenwilligen Stil, einer Ever Since We Met- Pledg- Mischung aus Soul und Country Music / his songs were covered ing My Love- My Girl Is Just by the Stones and Beatles. Unique country-soul music. Enough Woman For Me- SIL AUSTIN Volare (Nel Blu Dipinto Di SWINGSATION CD 547 876 € 16.75 Blu)- Old MacDonald (The Dogwood Junc tion- Wildwood- Slow Walk- Pink Shade Of Blue- Charg ers)- Dandilyon Walkin’ And Talkin’- Fine (The Charg ers)- CD-2:- Brown Frame- Train Whis- Give Me Love- I’ll Never -

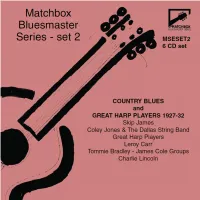

Dallas String Band with Coley Jones: Three Unknowns, Vcl; Acc

MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 1: MSESET1 (6 albums) MSE 201 COUNTRY BLUES – THE 1st GENERATION (1927) Series Editor: Johnny Parth MSE 202 BUDDY BOY HAWKINS (1927-29) Notes: Paul Oliver MSE 203 BO WEAVIL JACKSON (1926) Produced by: Gef Lucena MSE 204 RAGTlME BLUES GUITAR (1928-30) Remastering from 78s: Hans Klement, Austrophon Studios, Vienna MSE 205 PEG LEG HOWELL (1928-29) MSE 206 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 1 (1927-28) Digitising from vinyl: Norman White MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 3: MSESET3 (6 albums) MSE 213 MEMPHIS HARMONICA KINGS (1929-30) Original recordings from the collections of MSE 214 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 2 (1928-29) Werner Benecke, Joe Bussard, Johnny Parth, Guido van Rijn, MSE 215 RAMBLIN' THOMAS (1928-32) MSE 216 COUNTRY GIRLS (1926-29) Bernd Kuefferle, Hans Maitner MSE 217 RUFUS & BEN QUILLIAN (1929-31) MSE 218 DE FORD BAILEY & BERT BILBRO (1927-31) With thanks to Mark Jones of Bristol Folk Publications for the loan of MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 4: MSESET4 (6 albums) MSE 219 JULIUS DANIELS – LIL McCLlNTOCK (1927-30) vinyl LP copies of the original re-issue series MSE 220 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 3 (1929-30) MSE 221 PEG LEG HOWELL (1926-27) Sleeve Design: Bob Doling/Genny Lucena MSE 222 SANCTIFIED JUG BANDS (1928-30) MSE 223 ST. LOUIS BESSlE (1927-30) MSE 224 TEXAS ALEXANDER VOL. 4 (1934-50) Discographical details from Blues and Gospel Records 1902-1942 MATCHBOX BLUESMASTER SERIES: SET 5: MSESET5 (6 albums) by John Godrich and Robert Dixon MSE 1001 BLIND LEMON JEFFERSON (1926-29) MSE 1002 FRANK STOKES (1927-29) Considering the extreme rarity of the original 78s, condition is generally MSE 1003 BLIND BLAKE (1926-29) MSE 1004 BIG BILL BROONZY (1927-32) better than might be expected, but it must be borne in mind that only MSE 1005 MISSISSIPPI SHEIKS VOL. -

Bio Dave Alvin and Jimmie Dale Gilmore

Dave Alvin & Jimmie Dale Gilmore Downey to Lubbock Biography written by: Joe Nick Patoski Downey, California to Lubbock, Texas is a thousand-mile straight shot across the heart of the American West, with not much in between. The cities at each end of the line are one-time cowtowns that grew into symmetrically-platted working-class communities with very little to interrupt the horizon plane, making for big empty canvasses that require a vivid imagination to fill in all that blank space. Dave Alvin from Downey and Jimmie Dale Gilmore from Lubbock have been filling canvasses with music of the American West for decades, coming from two very different directions. The title track explains Alvin is a Strat-packing, wild blues Blaster, a nod to the roots rock band he formed with his brother Phil in 1978 before Dave peeled off to go his own way in 1986. He’s been part of the bands X, the Knitters, and the Flesh Eaters, tours relentlessly with his own band, the Guilty Ones, and continues apace on musical quests informed by his love of California and its history, and by Texas and the South, where most of the great music that was made in Los Angeles before and after the Second World War came from. Gilmore is the old Flatlander from the Great High Plains, acknowledging his first group, the folk-country trio formed in Lubbock 1972 with Joe Ely and Butch Hancock who continue performing and recording today. In addition to the Flatlanders and an extended solo career, he has been part of several ensembles including the Hub City Movers and The Wronglers with Warren Hellman, who started the Hardly, Strictly Bluegrass Festival in San Francisco. -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

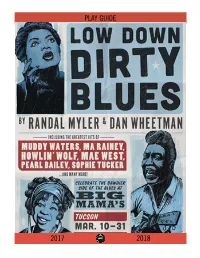

Low Down Dirty Blues R3

PLAY GUIDE 2017 2018 About ATC …………………………………………………………………………………..… 1 Introduction to the Play ………………………………………………………………………... 2 Song List …………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Meet the Creators ………………………………..…………………………………………….. 3 Meet the Characters ……………………………………………….……………………..…… 4 History of the Blues ……………..……..……………………………………………………… 4 Blues Around the World …..……..……………………………………………………………… 6 Who’s Got the Blues: References in the Play …..……..…………………………………………… 7 Glossary ……………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Discussion Questions & Activities ………………………………………………………………. 10 Low Down Dirty Blues Play Guide by Katherine Monberg, with contributions from ATC Learning & Education staff. SUPPORT FOR ATC’S LEARNING & EDUCATION PROGRAMMING HAS BEEN PROVIDED BY: APS Rosemont Copper Arizona Commission on the Arts Stonewall Foundation Bank of America Foundation Target Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona The Boeing Company City of Glendale The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Community Foundation for Southern Arizona The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc. Cox Charities The Lovell Foundation Downtown Tucson Partnership The Marshall Foundation Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Foundation Ford Motor Company Fund The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Stocker Foundation JPMorgan Chase The WIlliam L. and Ruth T. Pendleton Memorial Fund John and Helen Murphy Foundation Tucson Medical Center National Endowment for the Arts Tucson Pima Arts Council Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture Wells Fargo PICOR -

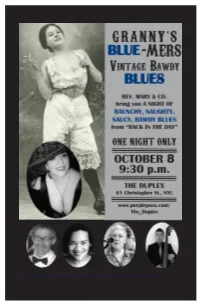

Blumer-Program.Pdf

Liz Courteney Rabson Lynn Schnore Wilds Reverend Mary Elizabeth Micari Dan Furman Nori Naraoka Directed & Produced by “Telephone Man” Reverend Mary Elizabeth Micari Written and Originally Sung by Meri Wilson in conjunction with Courteney Lynn Wilds and Dan Furman & Co. Genesis Repertory Ensemble, Inc. “My Handy Man” by Andy Razaf Arrangements by Dan Furman Originally Sung by Ethel Waters Costumes provided by Rev. Mary & Co. Reverend Mary & Co. Lighting and Sound by The Duplex “You Stole My Cherry” The Band Originally Sung by Lil Johnson & Black Bob Vocals and Percussion: Reverend Mary Liz Rabson-Schnore & Co. Vocals: Courteney Lynn Wilds Vocals, Ukulele, Harmonica: “Keep Your Hands Off It” Liz Rabson-Schnore Originally Sung by Lil Johnson & Black Bob Vocals, Piano: Dan Furman Courteney Lynn Wilds & Co. Bass : Nori Naraoka “Kitchen Man” by Bessie Smith, Andy Razaf, “Mighty Tight Woman” by Sippie Wallace Hezekiah Jenkins, Clarence Williams, Alex Reverend Mary & Co. Belldna (Edna B. Pinkard used the name Alex Belledna for her musical works) “King-Sized Papa” Originally Sung by Bessie Smith by Johnny Gomez & Paul Vance Reverend Mary Originally sung by Julia Lee Courteney Lynn Wilds & Co. “Sam The Hot Dog Man” Originally Sung by Lil Johnson & Black Bob “Stavin Chain” originally sung by Lil Johnson Reverend Mary Liz Rabson-Schnore “It Ain’t the Meat it’s the Motion” “A Guy What Takes His Time” by Henry Glover by Ralph Rainger Originally Sung by Maria Muldaur Originally Sung by Mae West Reverend Mary Reverend Mary “Sugar in My Bowl” by Clarence Williams, “My Daddy Rocks Me” James Tim Brymn, Dally Small Originally Sung by Trixie Smith & Mae West Originally Sung by Bessie Smith Reverend Mary & Co.