Frm 210 Forestry and Wildlife Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments on the Ornithology of Nigeria, Including Amendments to the National List

Robert J. Dowsett 154 Bull. B.O.C. 2015 135(2) Comments on the ornithology of Nigeria, including amendments to the national list by Robert J. Dowsett Received 16 December 2014 Summary.—This paper reviews the distribution of birds in Nigeria that were not treated in detail in the most recent national avifauna (Elgood et al. 1994). It clarifies certain range limits, and recommends the addition to the Nigerian list of four species (African Piculet Verreauxia africana, White-tailed Lark Mirafra albicauda, Western Black-headed Batis Batis erlangeri and Velvet-mantled Drongo Dicrurus modestus) and the deletion (in the absence of satisfactory documentation) of six others (Olive Ibis Bostrychia olivacea, Lesser Short-toed Lark Calandrella rufescens, Richard’s Pipit Anthus richardi, Little Grey Flycatcher Muscicapa epulata, Ussher’s Flycatcher M. ussheri and Rufous-winged Illadopsis Illadopsis rufescens). Recent research in West Africa has demonstrated the need to clarify the distributions of several bird species in Nigeria. I have re-examined much of the literature relating to the country, analysed the (largely unpublished) collection made by Boyd Alexander there in 1904–05 (in the Natural History Museum, Tring; NHMUK), and have reviewed the data available in the light of our own field work in Ghana (Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2014), Togo (Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2011a) and neighbouring Benin (Dowsett & Dowsett- Lemaire 2011, Dowsett-Lemaire & Dowsett 2009, 2010, 2011b). The northern or southern localities of species with limited ranges in Nigeria were not always detailed by Elgood et al. (1994), although such information is essential for understanding distribution patterns and future changes. For many Guineo-Congolian forest species their northern limit in West Africa lies on the escarpment of the Jos Plateau, especially Nindam Forest Reserve, Kagoro. -

Tree Species Diversity and Density Pattern in Afi River Forest Reserve, Nigeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 10, OCTOBER 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Tree Species Diversity And Density Pattern In Afi River Forest Reserve, Nigeria Aigbe H.I , Akindele S.O, Onyekwelu J, C Abstract: Afi River Forest Reserves in Cross River State, Nigeria, was assessed for tree species diversity and density pattern. Multistage (3 stage) sampling technique was adopted for data collection. 10 tertiary plots were randomly established within the secondary plots and trees randomly selected for measurement within the tertiary plots (0.20 ha). Growth data including: diameter at breast height (dbh, at 1.3m); diameters over bark at the base, middle and top; merchantable height and total height were collected on trees with dbh ≥ 10 cm in all the 10 tertiary sample plots. The results indicate that an average number of trees per hectare of 323 (68 species) were encountered in the study area. Population densities of the tree species ranged from 1 to 29 ha-1. This means, some tree species encountered translates to one stand per hectare. Pycnanthus angolensis was the most abundant with a total of 29 tree/ha. The basal area/ha in the study area was 102.77m2 and the species richness index obtained was 10.444, which indicate high species richness. The value of Shannon-Wiener Index (HI) is 3.827 which is quite high. The results show that the forest reserve is a well-stocked tropical rainforest in Nigeria. The high species diversity and the relative richness in timber species of the forest reserve does not correlate well with the abundance because the abundance of each of the species was quite low and density poor. -

The English Language and Tourism in Nigeria *

Joumal of the School Of General and BaSic Studies THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND TOURISM IN NIGERIA * Ngozi Anyachonkeya ABSTRACT Thispaper examines the role of English as a dynamic language in tapping and documenting the potentials and bounties of tourism in Nigeria. It argues that the English language is a potent instrument in harnessing tourism bounties of a people especially among the fifty-four member nations of the Commonwealth. In Nigeria the English language remains the most strategic language for the exploitation and marketing of tourism bounties available in the country. This is so because English is Nigeria's official language and language of unity in a multiethnic country like ours. In doing this, the paper makes a disclaimer. It is thefact that the author of thispaper is not an authority on Tourism. The burden of this paper therefore is to lay bare the indispensable role of English - a global dynamic language and language of globalization - in the i •• exploitation of tourism wealth of Nigeria, and in selling these bounties to world civilization for document. In the final analysis the paper makes the following declarations. We could practically do nothing without language. It is rather impossible that we could successfully discuss Tourism as an academic discipline in Nigeria in isolation of language, vis-a-vis, English, the arrowhead and 'DNA' of culture. In the same vein, it is rather a tragic mission to explore the bounties of Tourism in Nigeria and make same available to the global village outside the English language medium, in view of Nigeria's status as among the fifty-four member nations of the Commonwealth. -

Analysis of Poaching Activities in Kainji Lake National Park of Nigeria

Environment and Natural Resources Research; Vol. 3, No. 1; 2013 ISSN 1927-0488 E-ISSN 1927-0496 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Analysis of Poaching Activities in Kainji Lake National Park of Nigeria Henry M. Ijeomah1, Augustine U. Ogogo2 & Daminola Ogbara1 1 Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2 Department of Forestry and Wildlife Resources Management, University of Calabar, Nigeria Correspondence: Henry M. Ijeomah, Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Tel: 234-806-034-4776. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 2, 2012 Accepted: December 5, 2012 Online Published: December 15, 2012 doi:10.5539/enrr.v3n1p51 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/enrr.v3n1p51 Abstract Analysis of poaching activities in Kanji Lake National Park (KLNP) of Nigeria was conducted with the aim of investigating the forms and trend of encroachment experienced in the premier protected area, and to determine the locations where poaching occur. Data for the study were collected using two sets of structured questionnaires and secondary data obtained from administrative records. A set of structured questionnaires was administered randomly to 30% of households in ten selected communities close to the park. The second set of questionnaires was administered to 30% of the staff in park protection section of KLNP. In all 403 households and 53 staff members were sampled. Data on poaching arrest were obtained from administrative records. Data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics in form of frequencies of count, percentages, graphs, bar chart and pie chart. Grazing of livestock and hunting were the form of encroachment most arrested in the park between 2001 and 2009. -

Nigeria Biodiversity and Tropical Forestry Assessment

NIGERIA BIODIVERSITY AND TROPICAL FORESTRY ASSESSMENT MAXIMIZING AGRICULTURAL REVENUE IN KEY ENTERPRISES FOR TARGETED SITES (MARKETS) June 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. Cover photo: Harvested hardwood logs near Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary, Cross River State (Photo by Pat Foster-Turley) NIGERIA BIODIVERSITY AND TROPICAL FORESTRY ASSESSMENT MAXIMIZING AGRICULTURAL REVENUE IN KEY ENTERPRISES FOR TARGETED SITES (MARKETS) Contract No. 620-C-00-05-00077-00 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Section I: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 3 Section II: Major Ecosystems ............................................................................................. 5 Savanna, Grassland and the Arid North .................................................................. 5 Forests .................................................................................................................... -

Mineral / Salt Licks

Chapter 2 Species-Diversity Utilization of Salt Lick Sites at Borgu Sector of Kainji Lake National Park, Nigeria A. G. Lameed and Jenyo-Oni Adetola Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/51089 1. Introduction Mineral elements occur in the living tissues or soil in either large or small quantities. Those that occur in large quantities are called macro/major elements while those that occur in small quantities are called micro/minor/trace elements. These macro elements are required in large amount and the micro are required in small amount (Underwood, 1977, Alloway, 1990,) They occur in the tissues of plants and animals in varied concentrations. The magnitude of this concentration varies greatly among different living organisms and part of the organisms (W.B.E, 1995). Although most of the naturally occurring mineral elements are found in the animal tissues, many are present merely because they are constituents of the animal’s food and may not have essential function in the metabolism of the animals. Hence essential mineral elements refer to as mineral elements are those which had been proven to have a metabolic role in the body (McDonald, 1987). The essential minerals elements are necessary to life for work such as enzyme and hormone metabolisms (W.B.E, 1995). Enzymes are activated by trace elements known as metallo enzymes (Mertz, 1996). Ingestion or uptake of minerals that are deficient, inbalanced, or excessively high in a particular mineral element induces changes in the functions, activities, or concentration of that element in the body tissue or fluids. -

Trends of Game Reserves, National Park and Conservation in Nigeria

International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation Vol. 5(4), pp. 185-191, April 2013 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC DOI: 10.5897/IJBC11.127 ISSN 2141-243X ©2013 Academic Journals Review Trends in wildlife conservation practices in Nigeria Ejidike B. N.1* and Ajayi S. R.2 1Department of Ecotourism and Wildlife Management, Federal University of Technology, Akure Ondo State, Nigeria. 2Federal College of Wildlife Management, New Bussa, Niger State, Nigeria. Accepted 16 May, 2012 Civilization and development came with force of manipulations on the habitats of most wildlife so as to meet the needs of man. Urge for propagation and sustainability of wild flora and fauna brought about conservation practices that led to designating particular locations for their keeping. These areas are set aside to maintain functioning natural ecosystems to act as refuge for species and to maintain ecological processes. Forest and game reserves are the first protected areas created and maintained in Nigeria. They existed long before the creation of national parks in the country. Most of the game and forest reserves were upgraded and enacted to the status of national parks. In some situations like in Kainji Lake National park, Borgu Game Reserve and Zuguruma forest reserve were merged and enacted with decree No 46 of 1979 to be a national park. Conversion of some of the game reserves to national parks led to increase in the number of national parks. Key words: Borgu Game Reserve, Zuguruma Game Reserve, flora and fauna. INTRODUCTION At the onset of creation all creatures are living freely in landscapes areas are protected, managed and regulated the wild. -

Cross River Gorilla Gorilla Gorilla Diehli

Cross River Gorilla Gorilla gorilla diehli Gorilla Agreement Action Plan This Action Plan is based on the following document: Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli). Oates et. al. 2007. IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group and Conservation International, Arlington, VA, USA. Revised version of UNEP/CMS/GOR-MOP1/Doc.7b, November 2009 Incorporating changes agreed at the First Meting of the Parties to the Agreement on the Conservation of Gorilla and their Habitats (Rome, Italy, 29 November 2008) English Action Plans include additional editing not included in French versions. Action Plan Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) Species Range Nigeria, Cameroon Summary This plan outlines a programme of action that, if put into effect, could ensure the Cross River Gorilla‟s survival. The actions recommended are estimated to cost $4.6 million over a five-year period; around one-third of these funds have already been committed through government and donor support for general conservation efforts in the region. About $3 million therefore remains to be raised. The recommendations in this plan fall into two categories: recommendations for actions that need to be taken throughout the Cross River Gorilla‟s range, and site-specific recommendations. Among those that apply across the range of G. g. diehli are the following: • Given the nature of their distribution, a landscape-based approach should be taken for the conservation of Cross River Gorillas that must include effective cooperation by conservation managers across the Cameroon-Nigeria border. • There is a need to expand efforts to raise awareness among all segments of human society about the value of conservation in general and about the uniqueness of the Cross River Gorilla in particular. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Context for REDD in Nigeria

Federal Republic of Nigeria and Cross River State A Preliminary Assessment of the Context for REDD in Nigeria comissioned by the Federal Ministry of Environment, the Cross River State's Forestry Comission and UNDP researched & drafted by Macarthy Oyebo, Francis Bisong and Tunde Morakinyo with support from Environmental Resources Management (ERM) This report aims at providing basic information and a comprehensive assessment to ground a REDD+ readiness process in Nigeria, which is meant to advance with the support of the UN‐REDD Programme. The report is not a policy document, but rather an informative and analytical tool for all stakeholders willing to sustain REDD+ readiness in the country. The assessment places a special focus on Cross River State since this state is ready and willing to explore REDD+ readiness in a more intense fashion, in order to both inform the national REDD+ readiness with field‐level actions and to provide best practice and lessons for the rest of the states in the country. In addition, Cross River State holds a unique share of the forest and biodiversity resources of Nigeria; has two decades of active community forest management and community forest conservation experience to draw upon; and seeks to secure this legacy through innovative environmental finance schemes, such as REDD+. CONTENTS GLOSSARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1 1.1 OBJECTIVE OF THE REPORT 2 2 INVENTORY OF FOREST RESOURCES AND STATUS 5 2.1 THE STATUS OF THE FOREST RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT IN NIGERIA 5 2.2 THE STATUS OF VARIOUS -

1. Introduction 86

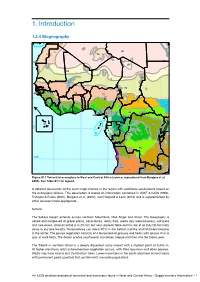

34 85 1. Introduction 86 69 30N 60 1.2.4 Biogeography87 88 93 65 95 98 96 92 97 94 111 99 62 61 35 100 101 115 36 25 70 2 39 83 102 37 38 59 71 1 4 3 4 6 7 5 10 40 44 116 9 103 104 31 12 11 13 16 0 73 41 8 18 14 45 15 17 66 20 47 72 27 43 48 46 42 19 118 112 10S 81 74 50 21 52 82 49 32 26 56 Figure S1.1 Terrestrial ecoregions in West and Central Africa (source: reproduced from Burgess et al. 75 2004). See Table S1.1 for legend. 106 51 119 33 55 64 53 67 63 84 A2 0detailedS description of the eight major biomes in the region with additional subdivisions based on76 29 the ecoregions follows. This description is based on information contained 5in8 WWF6 8& IUCN (1994), 30 Fishpool & Evans (2001), Burgess et al. (2004), and Happold & Lock (2013) and is supplemented57 by 114 other sources where appropriate. 107 54 Terrestrial ecoregions 105 109 113 Sahara Country boundary 22 77 78 The Sahara Desert extends across northern Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Chad. The topography11 7is 28 30S 79 varied and composed of gravel plains, sand dunes, rocky flats, wadis110 (dry watercourses), salt pans 108 23 and rare oases. Annual rainfall is 0–25 mm but very unpredictable and no rain at all may fall for many 0 250 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 80 years in any one locality. -

S INDEX to SITES

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – Index to sites ■ INDEX TO SITES A Anjozorobe Forest 523 Banc d’Arguin National Park 573 Blyde river canyon 811 Ankaizina wetlands 509 Bandingilo 888 Boa Entrada, Kapok tree 165 Aangole–Farbiito 791 Ankarafantsika Strict Nature Bangui 174 Boatswainbird Island 719 Aba-Samuel 313 Reserve 512 Bangweulu swamps 1022 Bogol Manyo 333 Aberdare mountains 422 Ankarana Special Reserve 504 Banti Forest Reserve 1032 Bogol Manyo–Dolo 333 Abijatta–Shalla Lakes National Ankasa Resource Reserve 375 Banyang Mbo Wildlife Sanctuary Boin River Forest Reserve 377 Park 321 Ankeniheny Classified Forest 522 150 Boin Tano Forest Reserve 376 Abraq area, The 258 Ankober–Debre Sina escarpment Bao Bolon Wetland Reserve 363 Boja swamps 790 Abuko Nature Reserve 360 307 Barberspan 818 Bokaa Dam 108 Afi River Forest Reserve 682 Ankobohobo wetlands 510 Barka river, Western Plain 282 Boma 887 African Banks 763 Annobón 269 Baro river 318 Bombetoka Bay 511 Aftout es Sâheli 574 Antsiranana, East coast of 503 Barotse flood-plain 1014 Bombo–Lumene Game Reserve Ag Arbech 562 Anysberg Nature Reserve 859 Barrage al Mansour Ad-Dhabi 620 209 Ag Oua–Ag Arbech 562 Arabuko-Sokoke forest 426 Barrage al Massira 617 Bonga forest 323 Aglou 622 Arâguîb el Jahfa 574 Barrage de Boughzoul 63 Boorama plains 787 Aguelhok 561 Arboroba escarpment 287 Barrage de la Cheffia 60 Bordj Kastil 969 Aguelmane de Sidi Ali Ta’nzoult Arbowerow 790 Barrage Idriss Premier 612 Bosomtwe Range Forest Reserve 616 Archipel d’Essaouira 618 Barrage Mohamed V 612 -

Cross River Gorillas Tami Santelli, IELP Law Clerk (July 20, 2005)

A World Heritage Species Case Study: Cross River Gorillas Tami Santelli, IELP Law Clerk (July 20, 2005) I. Introduction II. Taxonomy III. Status of Cross River Gorillas A. Nigeria B. Cameroon IV. Threats to Cross River Gorillas V. Proposals for Implementing the World Heritage Species Concept for Cross River Gorillas A. Protecting Habitat of the Cross River Gorilla B. Hunting and other Threats: Facilitating Cooperation Between Nigeria and Cameroon VI. Conclusions I. Introduction The Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) is the most endangered subspecies of gorilla, with a total population of 250-300 individuals living near the Nigeria-Cameroon border. These gorillas live in isolated subpopulations, generally in forested mountain areas. Although some subpopulations of Cross River gorillas live within protected areas, the immediate vicinity supports villages of people who use the forests for their everyday needs. This human use of the forest has fragmented gorilla habitat as the expansion of roads and agriculture isolate subpopulations. It has also led to opportunistic hunting of Cross River gorillas. Researchers are already involved in many efforts in Nigeria and Cameroon, and the governments of these two range states have made initial steps towards collaborating on conservation goals. However, enforcement of existing national laws is weak, and the countries lack the funds necessary to fully implement recommendations that arose out of bilateral meetings. To increase conservation efforts for the Cross River gorillas, these governments need the political will and in some cases additional funding for enforcement and continued collaboration, and the local people need incentives to stop exploiting the resources in gorilla habitat.