Downloaded by Anyone for Personal Usage (Gottlieb 2005: 162)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skate Catalogue2008

Concrete® Sportanlagen GmbH Skate Catalogue 2008 For the last 50 years Hermann Rudolph Baustoffwerk has been dealing with concrete. Therefore we are claiming to know all about the subtleties of this material. We have Skate Catalogue 2008 more than 150 employees as well as an in-house engi- neering and design department with 18 engineers and technicians. Furthermore we can now take advantage of the extensive experience we gained through design- ing and producing high-class elements for the building industry. This is of great benefit for our leisure facilities. Our leisure facilities are distributed by Concrete ® Spor- tanlagen GmbH. Concrete ® Sportanlagen GmbH www.concrete-skateparks.com www.concrete-sportanlagen.com [email protected] Ellhofen/Steinbißstr. 15 D-88171 Weiler-Simmerberg, Germany Phone +49/8384/8210-90 JAN 2008 DESIGN BY WWW.NZWG.DE Telefax +49/8384/8210-91 Contents General Information 4 Modular Elements 12 Grind Elements 36 Single Ramps 60 Funboxes 72 Run-up and Boundary Elements 96 Miniramps and Halfpipes 112 Pools/Mellows/Volcanoes 118 Accessories 160 General Information Skate Park Planning The most essential thing: the right contact By now Concrete® Skateparks are able to look back on many years of experience in the field of skate and BMX parks. Experience in cooperation with the target groups, the awarded engineering offices, the city councils and the mu- nicipalities shows that the creation of a fantastic and, and as a result also highly frequented, skate park is hardly possible without communication with everyone involved. Not every town planner or architect has the knowledge of what the local roller sportsmen would like to have for their recreational activities. -

So You Think You're As Good As the Dudes That Go on King of the Road? Well, Now's Your Time to Step Up: Thrasher Magazine'

So you think you’re aS good as the dudes that go on King of the Road? Well, now’s your time to step up: Thrasher magazine’s King of the Rad At-Home Challenge is your chance to bust and film the same tricks that the pros are trying to do on the King of the Road right now. The four skaters who land the most tricks and send us the footage win shoes for a year from Etnies, Nike SB, C1RCA, and Converse. You’ve got until the end of the King of the Road to post your clips—Monday, Oct 11th, at 11:59 pm. THE RULES King of the Rad Rules Contestants must film and edit their own videos The individual skater who earns the most points by landing and filming the most KOTR tricks, wins Hard tricks are worth 20 points Harder tricks are worth 30 points Hardest tricks are worth 50 points Fucked-Up tricks are worth 150 points (not available for some terrain) You can perform tricks from any category. The most points overall wins The top four skaters will be awarded the prize of free shoes for a year (that’s 12 pairs) from Nike SB, Converse, Etnies, and C1RCA All non-professional skaters are eligible to compete Deadline for posting footage is Oct. 11th, 11:59 pm Judging will be done by Jake Phelps, & acceptance of sketchy landings, etc will be at his discretion Meet the challenges to the best of your abilities and understanding. Any ambiguities in the wording of the challenges are unintentional. -

Development of a Skateboarding Trick Classifier Using Accelerometry And

Original Article Volume 33, Number 4, p. 362-369, 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2446-4740.04717 Development of a skateboarding trick classifier using accelerometry and machine learning Nicholas Kluge Corrêa1*, Júlio César Marques de Lima1, Thais Russomano2, Marlise Araujo dos Santos3 1 Aerospace Engineering Laboratory, Microgravity Center, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. 2 Center of Human and Aerospace Physiological Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine, King’s College, London, England. 3 Joan Vernikos Aerospace Pharmacy Laboratory, Microgravity Center, Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. Abstract Introduction: Skateboarding is one of the most popular cultures in Brazil, with more than 8.5 million skateboarders. Nowadays, the discipline of street skating has gained recognition among other more classical sports and awaits its debut at the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympic Games. This study aimed to explore the state-of-the-art for inertial measurement unit (IMU) use in skateboarding trick detection, and to develop new classification methods using supervised machine learning and artificial neural networks (ANN).Methods: State-of-the-art knowledge regarding motion detection in skateboarding was used to generate 543 artificial acceleration signals through signal modeling, corresponding to 181 flat ground tricks divided into five classes (NOLLIE, NSHOV, FLIP, SHOV, OLLIE). The classifier consisted of a multilayer feed-forward neural network created with three layers and a supervised learning algorithm (backpropagation). Results: The use of ANNs trained specifically for each measured axis of acceleration resulted in error percentages inferior to 0.05%, with a computational efficiency that makes real-time application possible. -

Italianpod101.Com Learn Italian with FREE Podcasts

ItalianPod101.com Learn Italian with FREE Podcasts Newbie Lesson First Impressions Can Last a Lifetime! Formal Italian 2 Formal English 2 1 Informal Italian 2 Informal English 2 Vocabulary 2 Grammar Points 3 Cultural Insight 4 ItalianPod101.com Learn Italian with FREE Podcasts Formal Italian Laura Buon giorno. John Buon giorno. Piacere di conoscerLa. Mi chiamo John Smith. Laura Piacere di conoscerLa. Mi chiamo Laura Rossi. Formal English Laura Good afternoon. John Good afternoon. Pleased to meet you. My name is John Smith. Laura Pleased to meet you. My name is Laura Rossi. Informal Italian Laura Ciao. John Ciao. Piacere di conoscerti. Mi chiamo John. Laura Piacere di conoscerti. Mi chiamo Laura. 2 Informal English Laura Hi. John Hi. Pleased to meet you. My name is John. Laura Pleased to meet you. My name is Laura. Vocabulary Italian English Class Ciao hello, hi, bye greeting expression Buon giorno Good morning, Good day, Good greeting expression afternoon Piacere di conoscerti. Pleased to meet you. greeting expression Mi chiamo... My name is... (lit. I call myself) phrase LC: 001_NB_L1_020408 © www.ItalianPod101.com - All Rights Reserved 2008-02-04 ItalianPod101.com Learn Italian with FREE Podcasts Vocabulary Sample Sentences Ciao, Laura. "Hello, Laura." Buon giorno, Luca. Good day, Luca. Piacere di conoscerti. Mi chiamo John. "Pleased to meet you. My name is John." Mi chiamo Peter. My name is Peter. Mi chiamo Luigi. My name is Luigi. Grammar Points The Focus of This Lesson is Italian Greetings Buon giorno. Ciao. "Good Afternoon. Hello." Ciao is the easiest and most common Italian greeting people use to say "hello" or "goodbye." You should only use this greeting with people whom you are well acquainted with, such as friends or relatives. -

9783608503289.Pdf

A B S O L U T E Holger von Krosigk Helge Tscharn S T R E E T Skateboard Streetstyle Book Tropen Vorwort 10 Einleitung 13 Sport oder Lifestyle? 19 Urbaner Dschungel 25 Rebellion 33 Was, Wie und Wo im Skateboarding 41 Absolute Beginners 48 Streetskating 50 (R)evolution Ollie 52 Frontside 180 Ollie 58 Backside 180 Ollie 60 Wheelies (Manuals) 62 Tail Wheelie 64 Nose Wheelie 66 Grinds und Slides 68 50-50 Grind 72 Noseslide 74 Frontside Noseslide 76 Crooked Grind 78 Boardslide 80 Frontside Tailslide 82 Backside Tailslide 84 Frontside Nosegrind 86 Bluntslide to Fakie 88 Feeble Grind 90 Nollies 92 Nollie 94 Nollie Backside 180 96 Nollie Heelflip 98 Nollie Lipslide 100 Kickflip (und Co.) 103 Kickflip 106 360 Flip 108 Frontside Pop-Shove it 110 Frontside Nollie Kickflip 112 Backside Nollie Heelflip 114 Fakie und Switch 117 Fakie Kickflip 120 Switch Heelflip 122 Switch Frontside 180 Kickflip 124 Fakie 50 / 50 126 Advanced Streetskating 128 Switch Backside Tailslide 128 Nosegrind Pop-out 130 Wallride 132 Noseslide am Handrail 134 360 Kickflip roof-to-roof 136 Casper 138 Elements of Street 140 Ledges und Curbs 142 Frontside Tailslide an einer Bank 148 Backside 50 / 50 an einer Leitplanke 150 Switch Noseslide to Fakie 152 Frontside 5-0 Grind 154 Frontside Boardslide an einem Curb 156 Nollie Tailslide 158 Ollie auf eine Tischtennisplatte 160 Noseslide an einer Tischtennisplatte 162 Frontside Nosebluntslide 164 Stufen und Gaps 167 Ollie 7 Stufen 170 Frontside 180 über ein Flatgap 172 Nollie Frontside 180 174 Backside 180 Kickflip 176 Frontside 180 Kickflip -

American Poets in Translation

Journal Journal ofJournal Italian Translation of Italian Translation V ol. XI No. 1 Spring 2016 Editor Luigi Bonaffini ISSN 1559-8470 Volume XI Number 1 Spring 2016 JIT 11-2 Cover.indd 1 8/11/2016 1:12:31 PM Journal of Italian Translation frontmatter.indd 1 8/12/2016 1:01:09 PM Journal of Italian Translation is an international Editor journal devoted to the translation of literary works Luigi Bonaffini from and into Italian-English-Italian dialects. All translations are published with the original text. It also publishes essays and reviews dealing with Ital- Associate Editors Gaetano Cipolla ian translation. It is published twice a year. Michael Palma Submissions should be in electronic form. Joseph Perricone Translations must be accompanied by the original texts, a brief profile of the translator, and a brief profile of the author. Original texts and transla- Assistant Editor tions should be on separate files. All submissions Paul D’Agostino and inquiries should be addressed to Journal of Italian Translation, Dept. of Modern Languages and Literatures, 2900 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210 Editorial Board Adria Bernardi or [email protected] Geoffrey Brock Book reviews should be sent to Joseph Per- Franco Buffoni ricone, Dept. of Modern Language and Literature, Barbara Carle Peter Carravetta Fordham University, Columbus Ave & 60th Street, John Du Val New York, NY 10023 or [email protected]. Anna Maria Website: www.jitonline.org Farabbi Rina Ferrarelli Subscription rates: Irene U.S. and Canada. Individuals $30.00 a year, $50 Marchegiani for 2 years. Francesco Marroni Institutions $35.00 a year. -

Jahresbericht 2003/04

Jahresbericht 2003/04 GRG23VBS Draschestraße IMPRESSUM HERAUSGEBER schulgemeinschaft des grg23vbs draschestraße FÜR DEN INHALT VERANTWORTLICH dir. mag. dr. fritz anzböck LEKTORAT UND INSERATE sabine heinrich LAYOUT karl herndler UMSCHLAG arbeiten aus textilem werken („vögel“) der 2. klassen von ursula tscherne DRUCK börsedruck wien wir danken folgenden FIRMEN für die schaltung eines inserates BUCHHANDLUNG REICHMANN (seite 44), GASTHAUS KOCI (seite 55), BLUMENHANDLUNG MARIA WEGSCHEIDER (seite 83), BLAGUSS REI- SEN GMBH (seite 101) INHALT " VORWORT 5 " UNSERE KLASSEN 6 " LEHRERI NNEN & VERWALTUNG 45 " COMENIUS 52 " OBERSTUFE NEU 56 " JUNGE LITERATUR 60 " DRAPETA 79 " EX LIBRIS 82 " SO EIN THEATER 84 " SPRACHEN 86 " SCHREIBWERKSTATT 91 " KUNSTWERKSTATT 102 " SPORT 109 " DENKSPORT 115 " INFORMATIK 117 " MATURA 118 " CHRONIK 126 " NACHWUCHS 130 VORWORT iebe Schülerinnen und Schüler! Sehr geehrte Eltern! met, der beabsichtigt Sie mit einigen ersten Infor- LLiebe Mitglieder des Kollegiums! mationen über unser großes Vorhaben zu versorgen. ben noch wünschte ich Ihnen am Ende des Schul- Nach einem arbeitsreichen Schuljahr bleibt mir nun nur Ejahres 2002/03 schöne noch die angenehme Aufgabe, Ihnen und Ihren Kindern Sommerferien, und schon ist ein schöne und erholsame Ferien und im Herbst dann einen weiteres Schuljahr vorüber und die guten Start ins neue Schuljahr zu wünschen. nächsten großen Ferien stehen vor der Tür! Wenn ich auf dieses Jahr zurück- blicke, so stand im heurigen Schul- jahr aus meiner Sicht eindeutig ein großes neues Projekt im Mittel- punkt, mit dem sich das Kollegium seit dem Herbst 2003 intensiv beschäftigt, und zwar der Schulversuch „Modulare Oberstufe“. Die Arbeit daran hat seither so große Fortschritte gemacht, dass ich zuver- sichtlich bin und mich schon jetzt darauf freue, Ihnen und natürlich den Schüler/innen dieses neue Angebot machen zu können! Autonome Freiheiten, die - wenn auch in bescheidenem Umfang - für die Unterstufe schon seit ca. -

Resource Guide 4

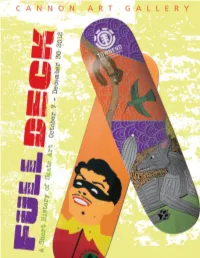

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

Burton Snowboards' Franck Waterlot Business of Wave

#89 DECEMBER/JANUARY 2018 €5 BURTON SNOWBOARDS’ FRANCK WATERLOT BUSINESS OF WAVE POOLS BRAND PROFILES, BUYER SCIENCE & MUCH MORE TREND REPORTS: FW18/19 SNOWBOARD BOOTS & BINDINGS, HELMETS & PROTECTION, SURF APPAREL, STREETWEAR, BACKPACKS, CRUISERS, SKATESHOES & SOCKS US Editor Harry Mitchell Thompson [email protected] HELLO #89 In this, the age of the influencer, *shudders*, that working together to elevate customer Skate Editor Dirk Vogel a brand’s message is now entrusted upon experience is easier than ever before. We [email protected] the distribution network/channels of these look forward to hearing of the next brands self-made pariahs. But is there anyone more to embrace bricks and mortar and work influential than the independent retailer? on building innovative relationships with Senior Snowboard Contributor They are the key opinion leaders and have retailers fit for 2018. authentic, real tribes of consumers who rely Tom Wilson-North on their expertise and wisdom. When they Returning for his annual outing, our [email protected] talk, their customers listen - they don’t just snowboard expert Tom Wilson-North slices simply click ‘like’. Yes, internet shopping is ‘n’ dices the FW18/19 snowboard boots & here to stay and those who haven’t adapted binding offer. Our Skateboard Editor, Dirk Senior Surf Contributor David Bianic have (sadly) fallen by the wayside, but a Vogel looks into the trends that’ll be popping [email protected] physical presence is more valuable than ever. at Bright/SEEK & Jacket Required for the In this issue’s Big Wig interview (p36) we men, while our German Editor, Anna Langer speak with Burton’s VP of Sales & Marketing, susses out streetwear hype for the ladies as Senior Wakeboard Contributor Tim Woodhead Franck Waterlot where he underlines the well as snow helmets and protection. -

Download the PDF Here

R: SOLLORS P: BLOTTO L: NORWAY ETTALA FOX SMITH KOOLEY KELLER MAAS EERO ETTALA BRYAN FOX AUSTIN SMITH JON KOOLEY MARKUS KELLER CHERYL MASS 11Nitro_Team_Dbl.indd 1 3/23/10 8:08 PM POP_AU_AUG10_holden.ai 1 8/16/10 4:28 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K MIKEY LeBLANC DARREL MATHES holdenouterwear.com in The Sailboat Tee in The Erwin Jacket ISSUE SIXTEEN The Finished Issue 20 32 44 52 68 76 Cover: ‘Classic’ Chad Muska PRODUCTS..............................16 ELECTRONICS..........................40 Photographer: Self portrait, Chad Muska. Thanks to: Rachael Wilson, Rene L’Estrange-Nickson, Luke Lucas, Jamie Driver, Katie Olsen, Annie Fox, Jana FILM.....................................28 GOOD TOGETHER.....................44 Bartolo, Steve Gourlay, Jan Snarski, Julius Kellar, Sophie Rowe Andrew Wood, Drew Baker, Marc Baker, Mathew Mickel, Cahill Bell-Warren, Bob Plumb, Shad Lambert, Lance Hakker, Mike Hakker, Chris Carey, Mark MUSIC...................................32 CHAD MUSKA..........................52 Catsburg. Address: EVIEWS EEgaN ALAIKA P.O. Box 6172, St Kilda Road Central R ...............................34 K V ....................60 Melbourne, Victoria, 8008 For advertising enquiries, please contact Dave on BUSINESS............................... JYE KEARNEY......................... 0407.147.124 or email [email protected] Australian Distribution: [email protected] 36 68 Feedback: [email protected] AUTO....................................38 SHYAMA BUTTONSHAW..............76 Pop Magazine is Dave Keating and Rick Baker. Brian in the Airbear. Mark Welsh photo / coalheadwear.com 15 Trucks ndent e p e d n I 10 PRODUCTS age Pro St Koston Tripping / IT’S THAT TIME OF YEAR agaIN. SNOWBOARD- ERS ARE LOOKING TO NORTH AMERICA FOR THEIR POW FIX, SURFERS ARE PLANNING THE SUMMER ROADTRIP UP (OR DOWN) THE COAST AND SKATERS FINALLY DON’T HAVE TO WORRY abOUT THE RAIN. -

Tony Hawkʼs Pro Skater 3 Game Design Suggestions Created

Tony Hawkʼs Pro Skater 3 Game Design Suggestions Created: October 2, 2000 Updated: October 3, 2000 Updated: November 7, 2000 Non-Confi dential: Written by Noe Valladolid Friends: Here is an unadulterated look at the Tony Hawkʼs Pro Skater suggestions submitted to Neversoft. Below in three sections are the pages as submitted in chronological order. The fi rst section is the feedback form all of the THPS2 World Finalists were asked to submit after playing through the game. The second section is the follow-up for suggestions I submitted to Neversoft after asking permission to do so. The third section contains the ideas that I missed or wanted to elaborate on. Enjoy, Noe Valladolid SECTION 1 Questionnaire: September, 2000 Thank you for taking the time to fi ll out this questionnaire regarding Tony Hawkʼs Pro Skater 2 and the Big Score Competition. Please fi ll out this questionnaire after you have thoroughly played all the levels in the game and email it back to me or send a hard copy. [email protected] Thanks! Name: Noe Valladolid Age: 25 What other console systems do you own besides PlayStation (highlight appropriate systems): Sega Dreamcast √ Nintendo 64 √ Nintendo Game Boy √ Which console systems do you intend to buy in the upcoming year (highlight desired systems): Sony PlayStation 2 √ Nintendo Game Cube (FKA “Dolphin”) Nintendo Game Boy Advance √ Microsoft X-Box What video games do you like to play (besides THPS 1 & 2)? Grind Session Sonic Adventure Tenchu 1&2 (not just because your Activision) Chrono Cross Crazy Taxi Gran Turismo Grandia Driver Soul Calibur Final Fantasy Tactics Pokémon Gold and Silver Pokémon Stadium Lunar 2 Lunar: Silver Star Parasite Eve Tactics Ogre Twisted Metal 2 Metal Gear Solid THE BIG SCORE COMPETITION This section discusses the THPS 2 Big Score Competition. -

The Outlook for Argentina's Renewable Energy Programs Nicolas R

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound International Immersion Program Papers Student Papers 2016 No Small Triumph : the Outlook for Argentina's Renewable Energy Programs Nicolas R. Oliver Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ international_immersion_program_papers Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Nicolas R. Oliver, "No small triumph : the outlook for Argentina's renewable energy programs," Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 17 (2016). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Immersion Program Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NO SMALL TRIUMPH: THE OUTLOOK FOR ARGENTINA’S RENEWABLE ENERGY PROGRAMS Nicolas R. Oliver | International Immersion Program – Argentina I. INTRODUCTION Argentina is not a leading voice in the global conversation on climate change, but it is a significant one. Geographically, Argentina has tremendous renewable energy potential, primarily in the areas of wind, hydroelectric, and biomass generation.1 And despite its developing country status, Argentina has passed ambitious laws to incentivize renewable energy utilization in the electricity and transportations sectors.2 Public concern over anthropogenic climate change in Argentina is also higher than in most other countries,3 likely due to the intense desertification, water scarcity, and glacial melt effects that 3.5–4ºC of warming would wreak on parts the country.4 Argentina should be a paradigmatic example of the type of country that the success of the Paris Climate Agreement depends upon—but so far, it isn’t.