Images Included in This Publication Are Sourced from Public Domain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Branches with Vacant Lockers

Union Bank of India List of Branches having Vacant Lockers State District Branch Name Branch Address Branch Adrress 2 Phone Andaman-Nicobar Andaman PORT BLAIR 10.Gandhi Bhavan, Aberdeen Bazar, Port Blair, Dist. Andaman, 233344 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur HINDUPUR Ground Floor, Dhanalakshmi Road, SD-Hindupur, Dist.Anantapur, 227888 Andhra Pradesh Ananthpur KIRIKERA At & Post Kirikera, Tal. Hindupur, Dist. Anantpur, Andhra Pradesh, 247656 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor SRIKALAHASTI 6-166, Babu Agraharam, Srikalahasti Town, PO Srikalahasti, S.Dist. Srikalahasti, 222285 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor PUNGANUR Survey No. 129, First Floor, Opp. MPDO Office, Madanapalle Road, PO Punganur, 250794 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari RAMACHANDRAPURAM D No:11-01 6/7,Jayalakshmi Complex, Nr Matangi hotel, Opp Town Bank, Main Road, PO & SD 9494952586 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari EETHAKOTA FI Mani Road Eethakota, Near Vedureswaram, Ravulapalem Mandal, Dist: East Godavari, 09000199511 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SAMALKOT D.No.11-2-24, Peddapuram Road, East Godavari District, Samalkot 2327977 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari MANDAPETA Door No. 34-16-7, Kamath Arcade, Main Road, Post Mandepeta, Dist. East Godavari, 234678 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari SARPAVARAM,KAKINADA DoorNo10-134,OPP Bhavani Castings,First Floor Sri Phani Bhushana Steel Pithapuram Road 2366630 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari TUNI Door No. 8-10-58, Opp. Kanyaka Parameswari Temple, Bellapu Veedhi, Tuni, Dist. 251350 Andhra Pradesh East Godavari VEDURESWARAM At&Post. Vedureswaram, Via Ravulapalem Mandal, Taluka Kothapet, Dist. East Godavari, 255384 KAMBALACHERUVU,RAJAHMUND Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Ground Floor,Yamuna Nilayam,DoorNo26-2-6, Koppisettyvari Street,PO Sriramnagar, 2555575 RY Andhra Pradesh Guntur RAVIPADU Door No.3-76 A, Main Road, PO Pavipadu (Guntur),S.Dist Narasaraopet 222267 Andhra Pradesh Guntur NARASARAOPET 909044 to 46, Bank Street, Arundelpet, P.O. -

List of State-Wise National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India

List of State-wise National Parks & Wildlife Sanctuaries in India Andaman and Nicobar Islands Sr. No Name Category 1 Barren Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 2 Battimalve Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 3 Bluff Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 4 Bondoville Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 5 Buchaan Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 6 Campbell Bay National Park National Park 7 Cinque Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 8 Defense Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 9 East Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 10 East Tingling Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 11 Flat Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 12 Galathea National Park National Park 13 Interview Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 14 James Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 15 Kyd Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 16 Landfall Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 17 Lohabarrack Salt Water Crocodile Sanctuary Crocodile Sanctuary 18 Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park National Park 19 Middle Button Island National Park National Park 20 Mount Harriet National Park National Park 21 Narcondum Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 22 North Button Island National Park National Park 23 North Reef Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 24 Paget Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 25 Pitman Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 26 Point Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary 27 Ranger Island Wildlife Sanctuary Wildlife Sanctuary -

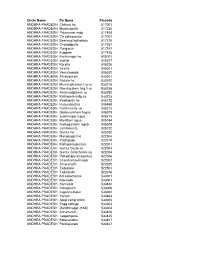

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

YES BANK LTD.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN Ground floor & First Arpan AND floor, Survey No Basak - NICOBAR 104/1/2, Junglighat, 098301299 ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Port Blair - 744103. PORT BLAIR YESB0000448 04 Ground Floor, 13-3- Ravindra 92/A1 Tilak Road Maley- ANDHRA Tirupati, Andhra 918374297 PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI, AP Pradesh 517501 TIRUPATI YESB0000485 779 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T. S. No. 2/5, Door no. 5-87-32, Lakshmipuram Main Road, Guntur, Andhra ANDHRA Pradesh. PIN – 996691199 PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur 522007 GUNTUR YESB0000587 9 Ravindra 1ST FLOOR, 5 4 736, Kumar NAMPALLY STATION Makey- ANDHRA ROAD,ABIDS, HYDERABA 837429777 PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD, D YESB0000424 9 MR. PLOT NO.18 SRI SHANKER KRUPA MARKET CHANDRA AGRASEN COOP MALAKPET REDDY - ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 64596229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD MALAKPET 500036 D YESB0ACUB02 4550347 21-1-761,PATEL MRS. AGRASEN COOP MARKET RENU ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA KEDIA - PRADESH HYDERABAD RIKABGUNJ 500002 D YESB0ACUB03 24563981 2-4-78/1/A GROUND FLOOR ARORA MR. AGRASEN COOP TOWERS M G ROAD GOPAL ANDHRA URBAN BANK SECUNDERABAD - HYDERABA BIRLA - PRADESH HYDERABAD SECUNDRABAD 500003 D YESB0ACUB04 64547070 MR. 15-2-391/392/1 ANAND AGRASEN COOP SIDDIAMBER AGARWAL - ANDHRA URBAN BANK BAZAR,HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 24736229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD SIDDIAMBER 500012 D YESB0ACUB01 4650290 AP RAJA MAHESHWARI 7 1 70 DHARAM ANDHRA BANK KARAN ROAD HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 D YESB0APRAJ1 23742944 500144259 LADIES WELFARE AP RAJA CENTRE,BHEL ANDHRA MAHESHWARI TOWNSHIP,RC HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD BANK BHEL PURAM 502032 D YESB0APRAJ2 23026980 SHOP NO:G-1, DEV DHANUKA PRESTIGE, ROAD NO 12, BANJARA HILLS HYDERABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABA PRADESH HYDERABAD BANJARA HILLS 500034 D YESB0000250 H NO. -

Survey and Documentation of Wild Varieties of Crop Plants in National

SURVEY AND DOCUMENTATION OF WILD VARIETIES OF CROP PLANTS IN NATIONAL PARK AND SANCTUARIES OF UPPER WESTERN GHATS (A Project Funded by the Protected Areas Programme of Forests and Wildlife Division of WWF-India) FINAL PROJECT REPORT January, 2001 Gene Campaign, New Delhi. 1 SURVEY AND DOCUMENTATION OF WILD VARIETIES OF CROP PLANTS IN NATIONAL PARK AND SANCTUARIES OF UPPER WESTERN GHATS Dr. Suman Sahai, Project Leader, Gene Campaign, J – 235 / A, Sainik Farms, Khanpur, New Delhi – 110062 Mr. S.M. Nadaf Junior Research Fellow, Pune (MS). Co-operation by, Dr. Y.S. Nerkar, Director of Research, Marathwada Agricultural University, Parabhani (MS). 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take immense pleasure in expressing my deep sense of reverence and gratitude towards Dr. Y.S. Nerkar, Director of Research, Marathwada Agricultural University, Parabhani for his valuable guidance and encouragement during the course of investigation. Without his efforts, it would not have been possible to complete this survey and report. I am much obliged to Adivasis, residing in remote areas of Sahyadri ranges of Western Ghats for their innocent help during excursion. I also take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to Dr. M.S. Kumbhojkar, Head, Dept. of Botany, Agharkar Research Institute, Pune, Dr. N.D. Jambhale, Professor, Dept. of Botany, Mahatma Phule Agriculture Universiry, Rahuri, Dr. S.D. Pradhan, D.K. Mishra, Mr. R. Manikanandan B.S.I., Pune and my friends Ravi Pawar, Sreerang Wanjerwadekar, Ravi Sufiyan Shaikh, Tanweer Shaikh, Mahesh Shindikar and Ashwini Deshpande for their co-operation, timely help and encouragement. Last but not the least, I express my heartfelt thanks to those who helped me either directly or indirectly during the present work. -

Historical Places

Where to Next? Explore Jammu Kashmir And Ladakh By :- Vastav Sharma&Nikhil Padha (co-editors) Magazine Description Category : Travel Language: English Frequency: Twice in a Year Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh Unlimited is the perfect potrait of the most beautiful place of the world Jammu, Kashmir&Ladakh. It is for Travelers, Tourism Entrepreneurs, Proffessionals as well as those who dream to travel Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh and have mid full of doubts. This is a new kind of travel publication which trying to promoting the J&K as well as Ladakh tourism industry and remove the fake potrait from the minds of people which made by media for Jammu,Kashmir&Ladakh. Jammu Kashmir and ladakh Unlimited is a masterpiece, Which is the hardwork of leading Travel writters, Travel Photographer and the team. This magazine has covered almost every tourist and pilgrimage sites of Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh ( their stories, history and facts.) Note:- This Magazine is only for knowledge based and fact based magazine which work as a tourist guide. For any kind of credits which we didn’t mentioned can claim for credits through the editors and we will provide credits with description of the relevent material in our next magazine and edit this one too if possible on our behalf. Reviews “Kashmir is a palce where not even words, even your emotions fail to describe its scenic beauty. (Name of Magazine) is a brilliant guide for travellers and explore to know more about the crown of India.” Moohammed Hatim Sadriwala(Poet, Storyteller, Youtuber) “A great magazine with a lot of information, facts and ideas to do at these beautiful places.” Izdihar Jamil(Bestselling Author Ted Speaker) “It is lovely and I wish you the very best for the initiative” Pritika Kumar(Advocate, Author) “Reading this magazine is a peace in itself. -

PROTECTED AREA UPDATE News and Information from Protected Areas in India and South Asia

T PROTECTED AREA UPDATE News and Information from protected areas in India and South Asia Vol. XXI, No. 3 June 2015 (No. 115) LIST OF CONTENTS Maharashtra 9 337 villages from nine talukas in Pune district grant EDITORIAL 3 no-objection to ESZ Tiger conservation and the construction of an Efforts to introduce solar irrigation pumps in Pench ‘urban conservation public’ TR buffer NTCA nod for release of a captive tigress in Pench NEWS FROM INDIAN STATES Tiger Reserve Assam 4 Illegal research carried out on animals at VJBU and 11 poachers killed, 20 arrested in Kaziranga National SGNP in 2001 Park this year Odisha 11 NGT asks Assam government to submit status report 70 lakh Olive ridley hatchlings in Odisha on restraining construction inside Manas NP CFR titles under the FRA distributed to villages in WWF-India and Apeejay Tea partner to reduce the Similipal TR human-elephant conflict in Assam Odisha Mining Corp to get Karlapat bauxite mines, Gujarat 5 part of which are inside the Karlapat WLS FD proposes drone surveillance for Gujarat forests Punjab 12 Jharkhand 6 Punjab to release gharials in Sutlej and Beas rivers Jharkhand working on a comprehensive 24/7 Rajasthan 13 elephant track-and-alert mechanism Tigers from Ranthambore TR moving into MP Karnataka 6 Five tigresses had 22 miscarriages in Sariska TR in NTCA approves tiger reserve status to Kudremukh; seven years state government disagrees Tamil Nadu 13 Dharwad-Belgavi railway line section turns death Plastic waste in elephant dung in Mudumalai, trap for wildlife Sathyamangalam and -

Bhadra Voluntary Relocation India

BHADRA VOLUNTARY RELOCATION INDIA INDIA FOREWORD During my tenure as Director Project Tiger in the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India, I had the privilege of participating in voluntary relocation of villages from Bhadra Tiger Reserve. As nearly two decades have passed, whatever is written below is from my memory only. Mr Yatish Kumar was the Field Director of Bhadra Tiger Reserve and Mr Gopalakrishne Gowda was the Collector of Chikmagalur District of Karnataka during voluntary relocation in Bhadra Tiger Reserve. This Sanctuary was notified as a Tiger Reserve in the year 1998. After the notification as tiger reserve, it was necessary to relocate the existing villages as the entire population with their cattle were dependent on the Tiger Reserve. The area which I saw in the year 1998 was very rich in flora and fauna. Excellent bamboo forests were available but it had fire hazard too because of the presence of villagers and their cattle. Tiger population was estimated by Dr. Ullas Karanth and his love for this area was due to highly rich biodiversity. Ultimately, resulted in relocation of all the villages from within the reserve. Dr Karanth, a devoted biologist was a close friend of mine and during his visit to Delhi he proposed relocation of villages. As the Director of Project Tiger, I was looking at voluntary relocation of villages for tribals only from inside Tiger Reserve by de-notifying suitable areas of forests for relocation, but in this case the villagers were to be relocated by purchasing a revenue land which was very expensive. -

Wild Life Sanctuaries in INDIA

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Wild Life Sanctuaries in INDIA Wildlife Sanctuaries in India are 441 in number. They are a home to hundreds and thousands of various flora and fauna. A wide variety of species thrive in such Wildlife Sanctuaries. With the ever growing cement – jungle, it is of utmost importance to protect and conserve wildlife and give them their own, natural space to survive Wildlife Sanctuaries are established by IUCN category II protected areas. A wildlife sanctuary is a place of refuge where abused, injured, endangered animals live in peace and dignity. Senchal Game Sanctuary. Established in 1915 is the oldest of such sanctuaries in India. Chal Batohi, in Gujarat is the largest Wildlife Sanctuary in India. The conservative measures taken by the Indian Government for the conservation of Tigers was awarded by a 30% rise in the number of tigers in 2015. According to the Red Data Book of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), there are 47 critically endangered species in India. DO YOU KNOW? Wildlife sanctuaries in India are established by IUCN category II protected areas. India has 537 wildlife sanctuaries referred to as wildlife sanctuaries category IV protected areas. Among these, the 50 tiger reserves are governed by Project Tiger, and are of special significance in the conservation of the tiger. Some wildlife sanctuaries in India are specifically named bird sanctuary, e.g., Keoladeo National Park before attaining National Park status. Many of them being referred as as a particular animal such as Jawai leopard sanctuary in Rajasthan. -

Eco-Tourism in Kerala and Its Importance and Sustainability

Volume : 3 | Issue : 5 | May 2014 ISSN - 2250-1991 Research Paper Economics ECO-Tourism In Kerala and Its Importance and Sustainability Assistant professor, Post Graduate Department of Economics Dr. Haseena V.A M.E.S Asmabi College, P.Vemballur, Kodunagllur, Thrissur, Kerala Tourism is one of the few sectors where Kerala has clear competitive advantages given its diverse geography in a short space ranging from the Western Ghats covered with dense forests to the backwaters to the Arabian sea. Its ancient rich culture including traditional dance forms and the strong presence of alternative systems of medicine add to its allure. Unfortunately, Kerala is dominated by domestic tourism within the state although foreign tourists arrivals to the state has been growing at a faster rate than national average. The goal in the KPP 2030 is to develop Kerala as an up-market tourism destination with the state being the top destination in terms of number of tourists and revenue among all the Indian states. Sustainable tourism is the mission. This can be achieved by integrating tourism with other parts of the economy like medical and health hubs which will attract more stable tourists over a longer period of time and with higher spending capacity. There will be new elements added to leisure tourism and niche products in tourism will be developed. Infrastructure development is ABSTRACT crucial to achieve this goal. The success of Kerala tourism will be based on the synergy between private and public sectors. The government has taken steps to encourage private investment in tourism, while adhering to the principles and practices of sustainability. -

PTERIDOPHYTE DIVERSITY in WET EVERGREEN FORESTS of SAKLESHPUR in CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS Sumesh N

Indian Journal of Plant Sciences ISSN: 2319–3824(Online) An Open Access, Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/jps.htm 2014 Vol.3 (1) January-March, pp. 28-39/Dudani et al. Research Article PTERIDOPHYTE DIVERSITY IN WET EVERGREEN FORESTS OF SAKLESHPUR IN CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS Sumesh N. Dudani1, 2, M. K. Mahesh2, M. D. Subash Chandran1 and *T. V. Ramachandra1 1Energy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560 012 2Department of Botany, Yuvaraja’s College (Autonomous), University of Mysore, Mysore - 57005 ABSTRACT The present study deals with the diversity of pteridophytes in the wet evergreen forests of Sakleshpurtaluk of Hassan district in central Western Ghats. A significant portion of the study area comprises of the Gundia river catchment region which is considered to be the ‘hottest hotspot of biodiversity’ as it shelters numerous endemic and threatened species of flora and fauna. Survey of various macro and micro habitats was carried out in this region, also a haven for pteridophytes. A total of 45 species of pteridophytes from 19 families were recorded in the study. The presence of South Indian endemics like Cyathea nilgirensis, Bolbitissub crenatoides, B. semicordata and Osmunda huegeliana signifies the importance of this region as a crucial centre of pteridophytes. Similar regions in the Western Ghats, rich in network of perennial streams have been targeted widely for irrigation and power projects. With regard to an impending danger in the form a proposed hydro-electric project in the Gundia River, threatening the rich biodiversity, an overall ecological evaluation was carried out in the entire river basin.