Radio Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Male Serial Killers and the Criminal Profiling Process: a Literature Review Jennifer R

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1996 Male Serial Killers and the Criminal Profiling Process: A Literature Review Jennifer R. Phillips Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Psychology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Phillips, Jennifer R., "Male Serial Killers and the Criminal Profiling Process: A Literature Review" (1996). Masters Theses. 1274. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1274 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Male Serial Killers and the Criminal Profiling Process: A Literature Review Jennifer R. Phillips Eastern Illinois University TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ....................................................... iv Acknowledgments ................................................. v Abstract ......................................................... vii ... Preface and Rationale .............................................. VIII CHAPTER 1: Understanding Serial Killers .............................. 1 Definitive Categories: Serial Killers. Serial Sexual Killers. and Serial Sadistic Killers .................................. 2 History and Incidence of Serial Killings ...........................6 Childhood History and Social Development ....................... 7 Motivational Model -

Marrakech of Marrakesh – Gideon Lewis-Kraus

Higher Atlas / Au-delà de l’Atlas – The Marrakech Biennale [4] in Context Marrakech of Marrakesh – Gideon Lewis-Kraus Marrakech from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia … known as the “Ochre city,” or the “Red city,” or the “Pink city,” depending on which guidebook you’re using, is the most important former imperial city in Morocco’s history. The city of Mar- rakech lies near the foothills of the snow-capped Atlas Mountains. It is the second-largest city in Morocco, after Casablanca. Like many North African cities, the city of Marrakech comprises both an old fortified city (the médina) and an adjacent modern city (called Gueliz) for a total population of 1,070,000. This Wikipedia page was accessed various times over the course of October and November 2011. Accord- ing to a wide array of local sources, the city’s population is approximately twice what Wikipedia claims it to be. Have you noticed the growth here? Enormous half-built luxury communities sprawl to the northeast, the east, the south. It is served by Ménara International Airport (IATE code: RAK) and a rail link to Casa- blanca and the north. On the train to Casablanca, I sat next to a middle-aged tourist guide in a rumpled black suit over an almost threadbare cream turtleneck. He wore knock-off designer eye- glasses, and was headed to Casablanca to meet a group of American tourists: he would take them around Casablanca, Rabat, Fez, Meknès, and finishing in Marrakech, where they would go shop- ping. He’d been out of work for eleven years until he started his own business as a guide. -

Automatic Call Distribution Description

Title page Nortel Communication Server 1000 Nortel Communication Server 1000 Release 4.5 Automatic Call Distribution Description Document Number: 553-3001-351 Document Release: Standard 3.00 Date: August 2005 Year Publish FCC TM Copyright © Nortel Networks Limited 2005 All Rights Reserved Produced in Canada Information is subject to change without notice. Nortel Networks reserves the right to make changes in design or components as progress in engineering and manufacturing may warrant. Nortel, Nortel (Logo), the Globemark, This is the Way, This is Nortel (Design mark), SL-1, Meridian 1, and Succession are trademarks of Nortel Networks. 4 Page 3 of 572 Revision history August 2005 Standard 3.00. This document is up-issued for Communication Server Release 4.5. September 2004 Standard 2.00. This document is up-issued for Communication Server 1000 Release 4.0. October 2003 Standard 1.00. This document is a new NTP for Succession 3.0. It was created to support a restructuring of the Documentation Library, which resulted in the merging of multiple legacy NTPs. This new document consolidates information previously contained in the following legacy documents, now retired: • Automatic Call Distribution: Feature Description (553-2671-110) • Automatic Call Distribution: Management Commands and Reports (553-2671-112) • Network ACD: Description and Operation (553-3671-120) Automatic Call Distribution Description Page 4 of 572 Revision history 553-3001-351 Standard 3.00 August 2005 12 Page 5 of 572 Contents List of procedures . 13 About this document . 17 Subject .. 17 Applicable systems . 17 Intended audience . 19 Conventions .. 19 Related information .. 20 ACD description . 21 Contents . -

Geographic Profiling : Target Patterns of Serial Murderers

GEOGRAPHIC PROFILING: TARGET PATTERNS OF SERIAL MURDERERS Darcy Kim Rossmo M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1987 DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the School of Criminology O Darcy Kim Rossmo 1995 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY October 1995 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Darcy Kim Rossmo Degree: ' Doctor of Philosophy Title of Dissertation: Geographic Profiling: Target Patterns of Serial Murderers Examining Committee: Chair: Joan Brockrnan, LL.M. d'T , (C I - Paul J. ~>ahtin~harp~~.,Dip. Crim. Senior Supervisor Professor,, School of Criminology \ I John ~ow&an,PhD Professor, School of Criminology John C. Yuille, PhD Professor, Department of Psychology Universim ofJritish Columbia I I / u " ~odcalvert,PhD, P.Eng. Internal External Examiner Professor, Department of Computing Science #onald V. Clarke, PhD External Examiner Dean, School of Criminal Justice Rutgers University Date Approved: O&Zb& I 3, 1 9 9.5' PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Universi the right to lend my thesis, pro'ect or extended essay (the title o? which is shown below) to users otJ the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

NO SILENCE to VIOLENCE Introduction

a report on violence against women in prostitution No silence in the UK to violence by the Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance ., Movement . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • • . • • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . SWARM would like to thank Basis Yorkshire, Decrim Now, the English Collective of Prostitutes and National Ugly Mugs for their support with producing this report. More details on these organisations can be found on page 37. This publication was produced by the Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement in December 2018. We have used pseudonyms to protect the women who shared their stories and to preserve their anonymity. This is report is specifically intended to reach people working in organisations and services tackling violence against women. Prostitution is undeniably a highly gen dered occupation - the vast majority of those buying sex are men, and the majority of those selling sex are women. In this report we use the term 'women in prostitution' and our focus -

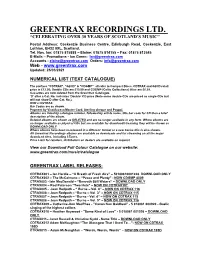

Text-Based Catalogue (Pdf)

GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LTD. “CELEBRATING OVER 30 YEARS OF SCOTLAND’S MUSIC” Postal Address: Cockenzie Business Centre, Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian, EH32 0XL, Scotland. Tel. Nos. Ian: 01875 815888 – Elaine: 01875 814155 – Fax: 01875 813545 E-Mails – Promotions - Ian Green: [email protected] Accounts - [email protected] Orders: [email protected] Web - www.greentrax.com Updated: 25/03/2021 NUMERICAL LIST (TEXT CATALOGUE) The prefixes "CDTRAX”, “G2CD” & “CDGMP” all refer to Compact Discs. CDTRAX and G2CD retail price is £12.00; Double CDs are £15.00 and CDGMP (Celtic Collections) titles are £6.99. Cassettes are now deleted from the Greentrax Catalogue. ‘D’ after a Cat. No. indicates ‘Double’ CD price (Note some double CDs are priced as single CDs but will not show D after Cat. No.), DVD’s: DVTRAX Bar Codes are as shown. Payment by Visa/Access/Master Card, Sterling cheque and Paypal. Albums are listed by catalogue number, followed by artiste name, title,bar code for CD then a brief description of the album. Deleted albums are shown as DELETED and are no longer available in any form. Where albums are no longer available as physical CDs but are available for download/streaming they will be shown as DOWNLOAD ONLY. Where albums have been re-released in a different format or a new Series this is also shown. All Greentrax Recordings albums are available as downloads and for streaming on all the major download sites, including I-Tunes. Price Lists for retailers, distributors an dealers are available on request. View our Download Full Colour Catalogue on our website: www.greentrax.com/music/catalogue GREENTRAX LABEL RELEASES: CDTRAX001 – Ian Hardie – “A Breath of Fresh Airs” – 50180810001228. -

SINISTER RESONANCE This Page Intentionally Left Blank SINISTER RESONANCE the Mediumship of the Listener

SINISTER RESONANCE This page intentionally left blank SINISTER RESONANCE The Mediumship of the Listener David Toop 2010 The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc 80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038 The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX www.continuumbooks.com Copyright © 2010 by David Toop All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Toop, David. Sinister resonance : the mediumship of the listener / by David Toop. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978- 1-4411-4972-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1- 4411-4972-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Music—Physiological effect. 2. Auditory perception. 3. Musical perception. I. Title. ML3820.T66 2010 781’.1—dc22 2009047734 ISBN: 978- 1-4411-4972-5 Typeset by Pindar NZ, Auckland, New Zealand Printed in the United States of America Contents Prelude: Distant Music vii PART I: Aeriel — Notes Toward a History of Listening 1 1. Drowned by voices 3 2. Each echoing opening; each muffl ed closure 27 3. Dark senses 39 4. Writhing sigla 53 5. The jagged dog 58 PART II: Vessels and Volumes 65 6. Act of silence 67 7. Art of silence 73 8. A conversation piece 107 PART III: Spectral 123 9. Chair creaks, but no one sits there 125 PART IV: Interior Resonance 179 10. Snow falling on snow 181 Coda: Distant Music 231 Acknowledgements 234 Notes 237 Index 253 v For Paul Burwell (1949–2007) drumming in some smoke- fi lled region — ‘And then the sea was closed again, above us’ — and Doris Toop (1912–2008) Prelude: Distant Music (on the contemplation of listening) Out of deep dreamless sleep I was woken, startled by a hollow resonance, a sudden impact of wood on wood. -

“Nosilence,Nosecrets”

s Knowsley SaSafeguardingfeguardingAdults t Board ets” l No Secr nce, u “No Sile d A g n i d r a u Knowsley g e f Board Safeguarding Adults a S Annual Report 2009/10 “No Silence, No Secrets” Welcome Anita Marsland MBE Chair Knowsley Safeguarding Adults Board Chief Executive - NHS Knowsley and Executive Director, Wellbeing Services Welcome to the 2009/10 annual report The Board can only operate if it is of the Knowsley Safeguarding Adults supported by partner organisations, staff Board. This is our third annual report and service providers, service users and and it details what we have achieved their families and the wider community. during 2009/10 and our plans for the During the year the Board has further year ahead. strengthened the safeguarding 2009/10 has been a busy year for partnership through a range of Safeguarding Adults both locally and collaborative working arrangements. nationally. In January 2010 the The Board Business Plan for 2010/11 Government announced that there would details how we will be taking this further be changes to the status of Safeguarding over the coming months. Adults Boards to put them on a statutory I hope you find this Report useful, either footing. This was in response to the great by raising awareness or identifying majority of responses received to the issues you can take forward in your own No Secrets review, including that from organisation as it is important that this is Knowsley, which recommended this a “working document”. We would also change. We are awaiting further welcome any feedback on how we can information but, given the strong improve the presentation of this partnership and firm commitment information in the future. -

SAM :: SAM Bulletin - Volume XLII, No

SAM :: SAM Bulletin - Volume XLII, No. 3 (Fall 2016) 7/17/18, 1'59 PM Custom Search About Us Membership Join or Renew Benefits Student Forum Institutions Listserv Conferences Future Conferences Montreal 2017 Past Conferences Perlis Concerts Awards & Fellowships Lowens Book Award Two Essays on Hearing Loss Lowens Article Award Dissertation Award Cambridge Award Varieties of Hearing Loss: Student Paper Award Volume XLII, No. 3 Block Fellowship A Lament for the Modern Ear (Fall 2016) Charosh Fellowship Cone Fellowship Contents Graziano Fellowship By Larry Starr Hampsong Fellowship Lowens Fellowship Two Essays on Hearing Back in the late 1960s, at the dawning of the Age of Over-Amplification, McCulloh Fellowship Loss McLucas Fellowship I marveled at the then-new phenomenon of individuals wearing Thomson Fellowship Tick Fellowship earplugs to rock music concerts. I wondered at that time what future “Varieties of Hearing Loss” Honorary Members anthropologists might say about a culture in which devices designed to Lifetime Achievement suppress sound were being voluntarily employed by people “Composing the Award Tinnitus Suites” Distinguished Service enthusiastically seeking out the very sounds they hoped to suppress. Citations Fifty years later, it would require extraterrestrial anthropologists to From the President Student Travel Subvention Funds find this phenomenon even worthy of comment. The hearing of Earth’s Digital Lectures contemporary urban dwellers has been systematically and mercilessly Proposed Amendment to Publications impacted by the volume levels of their own culture—musical and SAM Bylaws Journal of the Society for otherwise—to an extent that now ear-damaging amplification and noise American Music Forum for Early Career SAM Bulletin is simply accepted as a condition of normalcy. -

Płyty CD Z Muzyką

1 WYKONAWCA/KOMPOZYTOR TYTUŁ CZAS 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 1 ok.69 min. 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 2 ok.66 min. 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 3 ok.77 min. 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 4 ok.65 min. 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 5 ok.73 min. 100 ESSENTIAL POWER BALLADS 6 ok.73 min. 100 LAT FILHARMONII W WARSZAWIE ok.68 min. 16 FILM AND TV HITS ok.62 min. 2 CELLOS Celloverse ok.48 min. 2 CELLOS In2ition ok.47 min. 2 CELLOS 2 Cellos ok.43 min. 1994 PREVIEW DISC Składanka z muzyką klasyczną ok.75 min. 20 BRAVO HITS 1 ok.74 min. 20 BRAVO HITS 2 ok.78 min. 20 BRAVO HITS 3 ok.77 min. 20 BRAVO HITS 4 ok.77 min 20 BRAVO HITS 5 ok.74 min. 20 TOP DANCE HITS ok.71 min. 200 % DANCE HITS ok.72 min. 2019 NEW YEAR’S CONCERT CD 1 ok.56 min. CD 2 ok.54 min. 3 TENORS AT CHRISTMAS ok.61 min. 30 LAT TELEEXPRESSU CD 1 ok.78 min. CD 2 ok.73 min. 300 % HITS OF HAPPY NEW YEAR ‘97 ok.63 min. 500 % HITS OF SUNSHINE HOLIDAYS ok.71 min. 600 % HITS OF 1997 ok.62 min 70 LAT EMPIK : MUZYKA FILMOWA CD 1 ok.60 min. CD 2 ok.76 min. 700 % HITS OF ... CARNIVAL’98 ok.69 min. 80’ S COLLECTION : 1984 CD 1 ok.47 min. CD 2 ok.50 min. 800 % OF NEW DANCE HITS ok.70 min 900 % OF NEW DANCE HITS ok.71 min. A AALIYAH I Care 4 U ok.68 min. -

The Art of Silence

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The art of silence. Lydia Anne Kowalski University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Kowalski, Lydia Anne, "The art of silence." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2825. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2825 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ART OF SILENCE By Lydia Anne Kowalski B.S., Indiana University, 1971 M.C.P., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Lydia Anne Kowalski All rights reserved THE ART OF SILENCE By Lydia Anne Kowalski B.S., Indiana University, 1971 M.C.P., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973 A Dissertation Approved on November 6, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: _________________________________ Dissertation Director Dr. Ann Hall _________________________________ Second Committee Member Dr. Guy Dove _________________________________ Third Committee Member Dr. -

Investigating the Making of Cinematic Silence

Investigating the Making of Cinematic Silence Hasmik Gasparyan PhD by Creative Practice University of York Theatre, Film and Television June 2019 Abstract Despite extensive research on the notion of silence across a wide range of disciplines (music, philosophy, literature, architecture, theology) little is known about silence in film. The key concerns in the published literature on the topic are the relative nature of cinematic silence and its intrinsic connection to sound. This research will study directorial approaches applied by selected filmmakers in the construction and use of cinematic silence. It will then explore, through the design and production of the creative practice pieces submitted (a short and a feature-length documentary film), the notion of cinematic silence as a strong narrative device that can contribute to the representation of human experience and bring attention to questions related to cinematic language. 2 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Figures 6 List of Accompanying Material 7 Acknowledgments 8 Author’s Declaration 9 1. Introduction 10 2. Methodology: creative practice based research 13 2.1 The investigator’s background: a note of intention 13 2.2 Research question and literature review 15 2.3 Research Design 15 2.4 Qualitative methods 17 2.5 Case studies 18 2.6 Interviews with sound practitioners 18 2.7 Filmmaking as a research method 19 2.8 Conclusion 22 3. The key developments of ‘silence’ in cinema 23 3.1 Introduction 23 3.2 The emergence of cinematic silence as a concept 24 3.2.1 The ‘sound’ of silent films: 1894-1927 25 3.2.2 Technological innovations with coming of sound: 1927- 1971 26 3.2.3 Film Sound: 1927- late 1971 28 3.2.4 The second coming of Sound: 1971 - present 34 3.3 Classifications of silence in film 37 3.4 The concept of cinematic silence 45 3.4.1 Sound - silence contrast 47 3.4.2 Extended duration 48 3.4.3 Non-dominant image 50 3.4.4 Repetition 51 3.5 Conclusion 52 4.