Deakin Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infected Areas As on 1 September 1988 — Zones Infectées Au 1Er Septembre 1988 for Criteria Used in Compiling This List, See No

W kly Epiâem. Rec. No. 36-2 September 1S88 - 274 - Relevé àptdém, hebd N° 36 - 2 septembre 1988 GERMANY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF ALLEMAGNE, RÉPUBLIQUE FÉDÉRALE D’ Insert — Insérer: Hannover — • Gesundheitsamt des Landkreises, Hildesheimer Str. 20 (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 4) Delete — Supprimer: Hannover — • Gesundheitsamt (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 3) Insert — Insérer: • Gesundheitsamt der Landeshauptstadt, Weinstrasse 2 (Niedersachsen Vaccinating Centre No. HA 3) SPAIN ESPAGNE Insert - Insérer: La Rioja RENEWAL OF PAID SUBSCRIPTIONS RENOUVELLEMENT DES ABONNEMENTS PAYANTS To ensure that you continue to receive the Weekly Epidemio Pour continuer de recevoir sans interruption le R elevé épidémiolo logical Record without interruption, do not forget to renew your gique hebdomadaire, n’oubliez pas de renouveler votre abonnement subscription for 1989. This can be done through your sales pour 1989. Ceci peut être fait par votre dépositaire. Pour les pays où un agent. For countries without appointed sales agents, please dépositaire n’a pas été désigné, veuillez écrire à l’Organisation mon write to : World Health Organization, Distribution and Sales, diale de la Santé, Service de Distribution et de Vente, 1211 Genève 27, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. Be sure to include your sub Suisse. N’oubliez pas de préciser le numéro d’abonnement figurant sur scriber identification number from the mailing label. l’étiquette d’expédition. Because of the general increase in costs, the annual subscrip En raison de l’augmentation générale des coûts, le prix de l’abon tion rate will be increased to S.Fr. 150 as from 1 January nement annuel sera porté à Fr.s. 150 à partir du 1er janvier 1989. -

Perak Nature Oct/Nov 2009 Issue

Perak Nature – Oct/Nov 2009 edition Page 1 of 8 MNS Mission : To promote the study, appreciation, conservation and protection of Malaysia’s natural heritage, focusing on biological diversity and sustainable development. MNS Perak website : www.mnsperak.wordpress.com ● Email address: [email protected] ● Mailing address : P.O. Box 34, Ipoh Garden Post Office, 31407 Ipoh, Perak, Malaysia SELAMAT HARI RAYA AIDIL FITRI BRANCH EXCO 09 / 10 & Chairman Mr. Leow Kon Fah HAPPY DEEPAVALI 019-5634598 [email protected] Vice Chairman Mr Lee Ping Kong What’s new? 016-5655682 [email protected] What’s up? Hon. Secretary Ms. Georgia Tham Yim Fong 012-5220268 Who am I? True or False? [email protected] Chairman’s message Hon. Treasurer You are wanted… Mr. Har Wai Ming 019-5724113 New portfolio – PR & Communications [email protected] SIG news and events Committee Members Members say Mr. Ooi Beng Yean Let’s celebrate True or False? 017-5082206 [email protected] Mr Tou Jing Yi 1. Kinta Nature Park (KNP) 016-5441526 Project was first proposed [email protected] by MNS Perak Branch in Ms Lee Yuat Wah 017-5775641 the year 2000. [email protected] Mr Casey Ng Keat Chuan 2. One of the aims of the 019-5717008 KNP project is to set up [email protected] (Public Relations & Communications) more duck farms. Ms Ruhil Azhana Bt Jaafar 013-5284288 Ms Ng Kit Wan Answers inside…… 019-5439647 [email protected] (Editorial Board) Hon. Auditor Who am I? Mr. Edward Yong Chuen Soon Countdown 2010 70th Anniversary of MNS 40th Anniversary of MNS Perak Branch Membership expired or expiring soon? Renew now by contacting officer, Wee Chin at 03-22879422. -

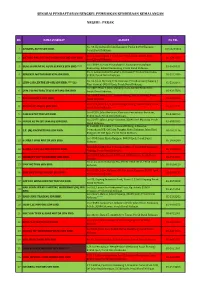

Senarai Pendaftaran Bengkel Pembaikan Kenderaan Kemalangan Negeri : Perak

SENARAI PENDAFTARAN BENGKEL PEMBAIKAN KENDERAAN KEMALANGAN NEGERI : PERAK BIL NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT NO TEL No. 60, Kg Sultan (Behind Rainbow Park), 31900 Kampar, 1 AMBANG AUTO SDN BHD. 016-5203502 Perak Darul Ridzuan. No. 12, Stesen Batu 2 1/2, Jalan Teluk Intan, 35500 Bidor, 2 BATANG PADANG AUTO SERVICES (M) SDN BHD. 05-4341300 Perak Darul Ridzuan. Lot 18884, Lorong Perusahaan 8, Kawasan Perusahaan 3 BENG KAMUNTNG AUTO SERVICE SDN BHD.**** 05-8910811 Kamunting, 34600 Kamunting, Perak Darul Ridzuan. No. 1, Laluan Industri Lahat 5, Kawasan Perindustrian Rima, 4 BENGKEL MOTOR KOK KEN SDN BHD. 31500, Perak Darul Ridzuan. 05-3222859 No. 11, Jalan Ng Song Teik, Kawasan Perindustrian Jelapang ( 5 CHIN CAR CENTRE (IPOH) SDN BHD.****(1) 05-5262206 First Garden) 30100 Ipoh, Perak Darul Ridzuan. Lot 2887, Batu 4, Jalan Maharaja Lela, 36000 Teluk Intan, 6 CUM YIN MOTOR (TELUK INTAN) SDN BHD. Perak Darul Ridzuan. 05-6215588 Lot 10853, Batu 2 1/2, Jalan Simpang, 34000 Taiping, Perak 7 DELIMA KINTA SDN BHD. Darul Ridzuan. 05-8481686 Lot 7470, Batu 3 1/2, Jalan Changkat Jong, 36000 Teluk Intan, 8 ENG HUAT ANSON SDN BHD. 05-6221742 Perak Darul Ridzuan. Lot 41319, Jalan Bercham, Kawasan Perusahaan Bercham, 9 FAH KEE MOTOR SDN BHD. 05-5468999 31400 Ipoh, Perak Darul Ridzuan. Lot 22971, Jalan Lumut-Sitiawan, 32040 Seri Manjung, Perak 10 FOKUS AUTO (SITIAWAN) SDN BHD. 05-6885055 Darul Ridzuan. Pt 160880 & 160881, Persiaran Klebang 1, Kawsan 11 G.F. (M) ENGINEERING SDN BHD. Perusahaan IGB, Off Jalan Tungku Abdul Rahman, Jalan Kual 05-2922116 Kangsar, 31200 Ipoh, Perak Darul Ridzuan. -

Recognising Perak Hydro's

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH echoechoYour Voice In The Community February 1-15, 2013 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 159 Malaysian Book Listen, Listen Believe in Royal Belum Yourself of Records World Drums and Listen broken at Festival 2013 Sunway’s Lost World of Tambun Page 3 Page 4 Page 6 Page 9 By James Gough Recognising Perak Hydro’s Malim Nawar Power Staion 2013 – adaptive reuse as a training Contribution to Perak and maintenance facility adan Warisan Malaysia or the Malaysian Heritage BBody, an NGO that promotes the preservation and conservation of Malaysia’s built Malim Nawar Power Station 1950’s heritage, paid a visit recently to the former Malim Nawar Power Station (MNPS). According to Puan Sri Datin Elizabeth Moggie, Council Member of Badan Warisan Malaysia, the NGO had forwarded their interest to TNB to visit MNPS to view TNB’s effort to conserve their older but significant stations for its heritage value. Chenderoh Dam Continued on page 2 2 February 1-15, 2013 IPOH ECHO Your Voice In The Community “Any building or facility that had made a significant contribution to the development of the country should be preserved.” – Badan Warisan Malaysia oggie added that Badan Warisan was impressed that TNB had kept the to the mining companies. buildings as is and practised adaptive reuse of the facility with the locating of Its standard guideline was MILSAS and REMACO, their training and maintenance facilities, at the former that a breakdown should power station. not take longer than two Moggie added that any building or facility that had made a significant contribution hours to resume operations to the development of the country should be preserved for future generations to otherwise flooding would appreciate and that power generation did play a significant part in making the country occur at the mine. -

No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Taiping 15 16 17 NEGERI PERAK

NEGERI PERAK SENARAI TAPAK BEROPERASI : 17 TAPAK Tahap Tapak No Kawasan PBT Nama Tapak Alamat Tapak (Operasi) 1 Batu Gajah TP Batu Gajah Batu 3, Jln Tanjung Tualang, Batu Gajah Bukan Sanitari Jalan Air Ganda Gerik, Perak, 2 Gerik TP Jln Air Ganda Gerik Bukan Sanitari D/A MDG 33300 Gerik, Perak Batu. 8, Jalan Bercham, Tanjung 3 Ipoh TP Bercham Bukan Sanitari Rambutan, Ipoh, Perak Batu 21/2, Jln. Kuala Dipang, Sg. Siput 4 Kampar TP Sg Siput Selatan Bukan Sanitari (S), Kampar, Perak Lot 2720, Permatang Pasir, Alor Pongsu, 5 Kerian TP Bagan Serai Bukan Sanitari Beriah, Bagan Serai KM 8, Jalan Kuala Kangsar, Salak Utara, 6 Kuala Kangsar TP Jln Kuala Kangsar Bukan Sanitari Sungai Siput 7 Lenggong TP Ayer Kala Lot 7345 & 7350, Ayer Kala, Lenggong Bukan Sanitari Batu 1 1/2, Jalan Beruas - Sitiawan, 8 Manjung TP Sg Wangi Bukan Sanitari 32000 Sitiawan 9 Manjung TP Teluk Cempedak Teluk Cempedak, Pulau Pangkor Bukan Sanitari 10 Manjung TP Beruas Kg. Che Puteh, Jalan Beruas - Taiping Bukan Sanitari Bukit Buluh, Jalan Kelian Intan, 33100 11 Pengkalan Hulu TP Jln Gerik Bukan Sanitari Pengkalan Hulu 12 Perak Tengah TP Parit Jln Chopin Kanan, Parit Bukan Sanitari 13 Selama TP Jln Tmn Merdeka Kg. Lampin, Jln. Taman Merdeka, Selama Bukan Sanitari Lot 1706, Mukim Jebong, Daerah Larut 14 Taiping TP Jebong Bukan Sanitari Matang dan Selama Kampung Penderas, Slim River, Tanjung 15 Tanjung Malim TP Penderas Bukan Sanitari Malim 16 Tapah TP Bidor, Pekan Pasir Kampung Baru, Pekan Pasir, Bidor Bukan Sanitari 17 Teluk Intan TP Changkat Jong Batu 8, Jln. -

Inventory Stations in Perak 40 Jps 210 False 20 Jps 41.4 False 00 00 Jps 339 False 45 Jps 1390 False

INVENTORY STATIONS IN PERAK PROJECT STESEN STATION NO STATION NAME FUNCTION STATE DISTRICT RIVER RIVER BASIN YEAR OPEN YEAR CLOSE ISO ACTIVE MANUAL TELEMETRY LOGGER LATITUDE LONGITUDE OWNER ELEV CATCH AREA STN PEDALAMAN 3813414 Sg. Trolak di Trolak WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Trolak Sg. Bernam 1946 TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 53 30 101 22 45 JPS 65.8 FALSE 3814413 Sg. Slim At Kg. Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 1930 07/72 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 51 00 101 28 45 JPS 314 FALSE 3814415 Sg. Bil At Jln. Tg. Malim-Slim WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Bil Sg. Bernam 1946 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 49 30 101 29 20 JPS 41.4 FALSE 3814416 Sg. Slim At Slim River WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Slim Sg. Bernam 11/66 TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE 03 49 35 101 24 40 JPS 455 FALSE 3901401 Sungai Bidor di Changkat Jong WL Perak Hilir Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3.99 101.1 FALSE 3907403 Sg.Perak di Kg.Pasang Api, Bagan Datok WL Perak Hilir Perak Muara Sg. Perak FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 3 59 17.37 100 45 55.69 FALSE 3911457 Sg. Sungkai At Jln. Anson-Kampar WL Perak Hilir Perak Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1950 07/83 FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 03 59 20 101 07 30 JPS 479 FALSE 3913458 Sg. Sungkai di Sungkai WL Perak Batang Padang Sg. Sungkai Sg. Perak 1930 TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE 03 59 15 101 18 50 JPS 289 FALSE 4011451 Sg. -

The Perak Development Experience: the Way Forward

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2013, Vol. 3, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Perak Development Experience: The Way Forward Azham Md. Ali Department of Accounting and Finance, Faculty of Management and Economics Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/437 Speech for the Menteri Besar of Perak the Right Honourable Dato’ Seri DiRaja Dr Zambry bin Abd Kadir to be delivered on the occasion of Pangkor International Development Dialogue (PIDD) 2012 I9-21 November 2012 at Impiana Hotel, Ipoh Perak Darul Ridzuan Brothers and Sisters, Allow me to briefly mention to you some of the more important stuff that we have implemented in the last couple of years before we move on to others areas including the one on “The Way Forward” which I think that you are most interested to hear about. Under the so called Perak Amanjaya Development Plan, some of the things that we have tried to do are the same things that I believe many others here are concerned about: first, balanced development and economic distribution between the urban and rural areas by focusing on developing small towns; second, poverty eradication regardless of race or religion so that no one remains on the fringes of society or is left behind economically; and, third, youth empowerment. Under the first one, the state identifies viable small- and medium-size companies which can operate from small towns. These companies are to be working closely with the state government to boost the economy of the respective areas. -

Collaboration, Christian Mission and Contextualisation: the Overseas Missionary Fellowship in West Malaysia from 1952 to 1977

Collaboration, Christian Mission and Contextualisation: The Overseas Missionary Fellowship in West Malaysia from 1952 to 1977 Allen MCCLYMONT A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Kingston University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. Submitted June 2021 ABSTRACT The rise of communism in China began a chain of events which eventually led to the largest influx of Protestant missionaries into Malaya and Singapore in their history. During the Malayan Emergency (1948-1960), a key part of the British Government’s strategy to defeat communist insurgents was the relocation of more than 580,000 predominantly Chinese rural migrants into what became known as the ‘New Villages’. This thesis examines the response of the Overseas Missionary Fellowship (OMF), as a representative of the Protestant missionary enterprise, to an invitation from the Government to serve in the New Villages. It focuses on the period between their arrival in 1952 and 1977, when the majority of missionaries had left the country, and assesses how successful the OMF was in fulfilling its own expectation and those of the Government that invited them. It concludes that in seeking to fulfil Government expectation, residential missionaries were an influential presence, a presence which contributed to the ongoing viability of the New Villages after their establishment and beyond Independence. It challenges the portrayal of Protestant missionaries as cultural imperialists as an outdated paradigm with which to assess their role. By living in the New Villages under the same restrictions as everyone else, missionaries unconsciously became conduits of Western culture and ideas. At the same time, through learning local languages and supporting indigenous agency, they encouraged New Village inhabitants to adapt to Malaysian society, while also retaining their Chinese identity. -

THE ACTION PLAN of FULL EMPLOYMENT for PERAK Action, Strategies, Programme & Projects

UNIVERSITI ISLAM ANTARABANGSA (UIA) THE ACTION PLAN OF FULL EMPLOYMENT FOR PERAK Action, Strategies, Programme & Projects Prof Sr Dr Khairuddin A Rashid Asst Prof Dr Mariana Mohamed Osman Asst Prof Dr Syafiee Shuib Introduction to the team of researchers Employment policies Tourism pangkor Effectiveness of local Public transport in authorities Kerian Prof Sr Dr Khairuddin A Prof Dato Dr Mansor Ibrahim Assistant Prof Dr Mariana Asst Prof Dr Syahriah Rashid (lead researcher) (lead Researcher) (tourism Mohamed Osman Bachok (PHD in Traffic (procurement and public planning and environmental Engineering) private partnership) resource management Assistant Prof Dr Mariana Assistant Prof Dr Mariana Associate Prof Dr Mohd Zin Asst. Prof Dr Mariana Mohamed Osman (Phd in Mohamed Osman Mohamed (local government and Mohamed Osman community development and Assistant Prof Dr Syahriah public administration) Governance Bachok Assistant Prof Dr Syafiee Muhammad Faris Abdullah Asst Prof Dr Syahriah Bachok Shuib (Phd in Affordable (Phd in GIS and land use Housing) planning Suzilawati Rabe (Phd Shaker Amir (Phd candidate in Nurul Izzati Mohd Bakri (MSBE) Zakiah Ponrohono (Phd Candidate in regional Tourism Economic) Nuraihan Ibrahim (MSBE) candidate in sustainable economic ) Anis Sofea Kamal (BURP) Tuminah Paiman (MSBE) transportation) Shazwani Shahir (Master of Siti Nur Alia Thaza (MSBE) Ummi Aqilah (MSBE) Built Environment Azizi Zulfadli (MSBE) Siti Aishah Ahmad (BURP) Siti Hajar (BURP) Sadat (BURP) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY P From 2000 until 2011: Malaysia unemployment rate averaged at 3.37%. R Rate of unemployed in Malaysia was at 3.3% in 2010 and reduced further to 3.1% in 2011. O In term of Perak the unemployment rate was at (27300) 3.0% in 2010 and further reduced to B (24900) 2.6% in 2011. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Study Tin mining is one of the oldest industries in Malaysia. As what had been researched by James R.Lee (2000), the tin mining started since 1820s in Malaysia after the arrival of Chinese immigrants. The Chinese immigrants settled in Perak and started tin mines. Their leader was the famous Chung Ah Qwee. Their arrival contributed to the needed labour and hence the growth of the tin mining industry. Tin was the major pillars of the Malaysian economy. Tin occurs chiefly as alluvial deposits in the foothills of the Peninsular on the western site. The most important area is the Kinta Valley, which includes the towns of Ipoh, Gopeng, Kampar and Batu Gajah in the state of Perak. But that was long ago before price of tin had fallen greatly and high cost of mining had shutdown the industry. What is left now is the abandoned mine site scattered all over Perak. Some mines are far from populated area and some are in the population itself such as Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (UTP). The campus is located on land that was once an active tin mining site. The residual of past activities can be seen where number of mining ponds can be found scattered in the vicinity of UTP. The main concern from geologist and nature agencies are the identification of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) and the level of concentration for each element found in the area. Until now, there are only a few numbers of studies in Malaysia that has been done on data collection of PTEs and elevated content of PTEs in former mine. -

Royal Belum State Park

Guide Book Royal Belum State Park For more information, please contact: Perak State Parks Corporation Tingkat 1, Kompleks Pejabat Kerajaan Negeri, Daerah Hulu Perak, JKR 341, Jalan Sultan Abd Aziz, 33300 Gerik, Perak Darul Ridzuan. T: 05-7914543 W: www.royalbelum.my Contents Author: Nik Mohd. Maseri bin Nik Mohamad Royal Belum - Location 03 Local Community 25 Editors: Roa’a Hagir | Shariff Wan Mohamad | Lau Ching Fong | Neda Ravichandran | Siti Zuraidah Abidin | Introduction 05 Interesting Sites and Activities Christopher Wong | Carell Cheong How To Get There 07 within Royal Belum 29 Design & layout: rekarekalab.com Local History 09 Sites and Activities 31 ISBN: Conservation History 11 Fees And Charges 32 Printed by: Percetakan Imprint (M) Sdn. Bhd. Organisation of Royal Belum State Park 13 Tourism Services and Accommodation in 33 Printed on: FSC paper Physical Environment 14 Belum-Temengor 35 Habitats 15 Useful contacts 36 Photo credits: WWF-Malaysia Biodiversity Temengor Lake Tour Operators Association 37 Tan Chun Feng | Shariff Wan Mohamad | Mark Rayan Darmaraj | Christopher Wong | Azlan Mohamed | – Flora 17 Conclusion 38 Lau Ching Fong | Umi A’zuhrah Abdul Rahman | Stephen Hog | Elangkumaran Sagtia Siwan | – Fauna 19 - 22 Further Reading Mohamad Allim Jamalludin | NCIA – Avifauna 23 Additional photos courtesy of: Perak State Parks Corporation 02 Royal Belum – Location Titiwangsa Range and selected National and State Parks in Peninsular Malaysia. KEDAH Hala Bala THAILAND Wildlife Sanctuary PERLIS Bang Lang STATE PARK National Park -

Higher-Resolution Biostratigraphy for the Kinta Limestone and an Implication for Continuous Sedimentation in the Paleo-Tethys, Western Belt of Peninsular Malaysia

Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences Turkish J Earth Sci (2017) 26: 377-394 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/earth/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/yer-1612-29 Higher-resolution biostratigraphy for the Kinta Limestone and an implication for continuous sedimentation in the Paleo-Tethys, Western Belt of Peninsular Malaysia 1,2, 2 3 4 2 5 Haylay TSEGAB *, Chow Weng SUM , Gatovsky A. YURIY , Aaron W. HUNTER , Jasmi AB TALIB , Solomon KASSA 1 South-East Asia Carbonate Research Laboratory (SEACaRL), Department of Geosciences, Faculty of Geosciences and Petroleum Engineering, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Bandar Seri Iskandar, Perak Darul Ridzuan, Malaysia 2 Department of Geosciences, Faculty of Geosciences and Petroleum Engineering, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Bandar Seri Iskandar, Perak Darul Ridzuan, Malaysia 3 Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russian Federation 4 Department of Applied Geology, Western Australian School of Mines, Curtin University, Perth, Australia 5 Department of Applied Geology, School of Applied Natural Sciences, Adama Sciences and Technology University, Adama, Ethiopia Received: 29.12.2016 Accepted/Published Online: 21.09.2017 Final Version: 13.11.2017 Abstract: The paleogeography of the juxtaposed Southeast Asian terranes, derived from the northeastern margins of Gondwana during the Carboniferous to Triassic, resulted in complex basin evolution with massive carbonate deposition on the margins of the Paleo- Tethys. Due to the inherited structural and tectonothermal complexities, discovery of diagnostic microfossils from these carbonates has been problematic. This is particularly the case for the Kinta Limestone, a massive Paleozoic carbonate succession that covers most of the Kinta Valley in the central part of the Western Belt of Peninsular Malaysia.