Zombie Is a Slave Forever About:Reader?Url=

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: a Late Modern Enchantment

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: A Late Modern Enchantment Daniel S. Wise New Haven, CT Bachelor oF Arts, Florida State University, 2010 Master oF Arts, Florida State University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty oF the University oF Virginia in Candidacy For the Degree oF Doctor oF Philosophy Department oF Religious Studies University oF Virginia November, 2020 Committee Members: Erik Braun Jack Hamilton Matthew S. Hedstrom Heather A. Warren Contents Acknowledgments 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 2 From Spiritualism to Ghost Hunting 27 Chapter 3 Ghost Hunting and Scientism 64 Chapter 4 Ghost Hunters and Demonic Enchantment 96 Chapter 5 Ghost Hunters and Media 123 Chapter 6 Ghost Hunting and Spirituality 156 Chapter 7 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 196 Acknowledgments The journey toward competing this dissertation was longer than I had planned and sometimes bumpy. In the end, I Feel like I have a lot to be thankFul For. I received graduate student Funding From the University oF Virginia along with a travel grant that allowed me to attend a ghost hunt and a paranormal convention out oF state. The Skinner Scholarship administered by St. Paul’s Memorial Church in Charlottesville also supported me For many years. I would like to thank the members oF my committee For their support and For taking the time to comb through this dissertation. Thank you Heather Warren, Erik Braun, and Jack Hamilton. I especially want to thank my advisor Matthew Hedstrom. He accepted me on board even though I took the unconventional path oF being admitted to UVA to study Judaism and Christianity in antiquity. -

South Sudan Votes to Split North

Iowa State Daily, February 2011 Iowa State Daily, 2011 2-8-2011 Iowa State Daily (February 08, 2011) Iowa State Daily Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2011-02 Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Iowa State Daily, "Iowa State Daily (February 08, 2011)" (2011). Iowa State Daily, February 2011. 20. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/iowastatedaily_2011-02/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State Daily, 2011 at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Iowa State Daily, February 2011 by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Flavors: How food cravings match personality traits FLAVORS.p8 >> TUESDAY February 8, 2011 | Volume 206 | Number 95 | 40 cents | An independent student newspaper serving Iowa State since 1890. ™ iowastatedaily.com facebook.com/iowastatedaily iowastatedaily online Sudan Referendum South Sudan votes to split North South Sudanese refugees across the world stood in line to vote on the Sudanese referendum Jan. 9. Results from the election show that a large majority of South Sudanese voted to split from the North, which will allow for the formation of the Republic of South Sudan on July 9, when the Comprehensive Peace Act expires. File photo: Matt Wettengel/Iowa State Daily Students reflect on nation’s newfound independence Obama: outstanding disputes must be resolved peacefully By Katherine.Marcheski the war-torn region or escape for a chance at a Khartoum, Sudan -- Final results of last from its list of terrorism sponsors, Department iowastatedaily.com better life. -

'She Will Be Sorely Missed'

Volume 46 March 26, Issue 10 2007 small ALK The Student Voice of Methodist university www.smalltalkmc.comT ‘SHE WILL BE SORELY MISSED’ “Christ shall come with shout of acclamation and take me home, what joy shall fill my heart.” From her favorite hymn, “How Great Thou Art” Ashley Genova News Editor On Mon, March 19 Dr. Wenda Johnson, the Interim Vice President for Academic Affairs, was found dead in her home. Johnson was 58. The cause of her death is not yet known. Johnson was born on Oct. 20, 1948, in Minneapolis Minnesota. Johnson came to Methodist on Aug. 14 of 1991 and served as the chair of the Physical Education Department. She was the first person at Methodist with a doctorate in Physical Education. Continued on page 2 Above photo courtesy of Melissa Jameson. Other photos by Ashley Genova. 2 smallTALK March 26, 2007 Volume 46, Issue 10 Reverend Dr. Michael Safley speaks to audience while other speakers One Spirit sings “Thy Will Be Done” sit in the background. All photos by Ashley Genova Continued from page 1 one to be grateful for Johnson’s dent Development and Services a wonderful woman, life on Earth he said several and Dean of Students. “She was bright, smart and fun- Johnson also played an impor- prayers thanking God for her. a strong advocate for the highest ny. We’ll have a hard tant part as dean of the School Following, members of the con- standards of academic achieve- time replacing her-no of Science and Human Devel- gregation shared memories that ment by all concerned with the doubt,” said Kevin opment by advising to the vice they had of Johnson throughout educational process, but she was Page, Student Gov- president of Academic Affairs. -

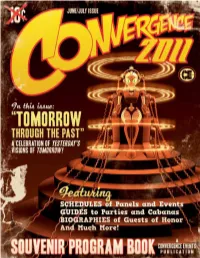

Souvenir & Program Book (PDF)

THAT STATEMENT CONNECTS the modern Steam Punk Movement, The Jetsons, Metropolis, Disney's Tomorrowland, and the other items that we are celebrating this weekend. Some of those past futures were unpleasant: the Days of Future Past of the X-Men are a shadow of a future that the adult Kate Pryde wanted to avoid when she went back to the present day of the early 1980s. Others set goals and dreams; the original Star Trek gave us the dreams and goals of a bright and shiny future t h a t h a v e i n s p i r e d generations of scientists and engineers. Robert Heinlein took us to the Past through Tomorrow in his Future History series, and Asimov's Foundation built planet-wide cities and we collect these elements of the past for the future. We love the fashion of the Steampunk movement; and every year someone is still asking for their long-promised jet pack. We take the ancient myths of the past and reinterpret them for the present and the future, both proving and making them still relevant today. Science Fiction and Fantasy fandom is both nostalgic and forward-looking, and the whole contradictory nature is in this year's theme. Many of the years that previous generations of writers looked forward to happened years ago; 1984, 1999, 2001, even 2010. The assumptions of those time periods are perhaps out-of-date; technology and society have passed those stories by, but there are elements that still speak to us today. It is said that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is when you are 13. -

V6F Fall 2017 Volume 1

SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY VOLUME 7 FALL 2017 ISSUE 1 THE MEME MADE ME DO IT! THE FUTURE OF IMMERSIVE ENTERTAINMENT AND TORT LIABILITY JASON ZENOR* ABSTRACT In June of 2014, two teenage girls lured their friend into the woods and stabbed her nineteen times. The heinousness of the act itself was enough to make it a national news story. But the focus of the story turned to the unique motive of the crime. The girls wanted to appease the Slender Man, an evil apparition who had visited them in their sleep and compelled them to be his proxies. Many people had never heard of the Slender Man, a fictional internet meme with a sizeable following of adolescents fascinated with the macabre. Soon the debate raged as to the power and responsibility of such memes. As for legal remedies, media defendants are rarely held liable for harms caused by third parties. Thus, the producers of this violent meme are free from liability. But this law developed in an era of passive media where there was distance between the media and audience. This paper examines how media liability may change as entertainment becomes more immersive. First, this paper examines the Slender Man phenomenon and other online memes. Then it outlines negligence and incitement law as it has been applied to traditional entertainment products. Finally, this paper posits how negligence and incitement law may be applied differently in future cases against immersive media products that inspire real-life crimes. * Jason Zenor is an Associate Professor for the School of Communication, Media, and Arts at State University of New York- Oswego. -

Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES a Watchung Communications, Inc

HappyHappy ThanksgivingThanksgiving Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, November 26, 2009 OUR 119th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 48-2009 Periodical – Postage Paid at Rahway, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Donations Sought to Help Families In Need During Holiday Season By MARYLOU MORANO ing individuals and families in need nications for The Community Food Specially Written for The Westfield Leader through its “Adopt a Food Pantry.” Bank of New Jersey in Hillside. “The AREA – With the weakened Area schools adopt a food pantry and need is up 67 percent from just two economy, many local residents are students are encouraged to bring do- years ago.” still in need of food and clothing. This nations to school with them, and the For Thanksgiving, a total of 35 holiday season, many local congre- county will distribute the supplies to turkey drive sites donated 2,898 fro- gations and organizations will con- the food pantries. The non-perish- zen turkeys, and Westfield’s First duct food, clothing and other drives able foods needed most are cereals, Union School brought in 102 tur- in an effort to lend a hand. infant formula, milk (canned, boxed, keys, 1,020 pounds of food and $124. “There are approximately 30 food or powered), juice (boxed or canned) In total, The Community Food Bank, pantries in the county and all urgently peanut butter, and canned or pack- which assists low-income people in need supplies,” said Union County aged foods such as meat, fish, veg- 18 of New Jersey’s 21 counties, re- Freeholder Chairman Alexander etables, macaroni and cheese, soups, ceived 2,898 frozen turkeys from the Mirabella. -

Ttabvue-91214199-OPP-36.Pdf

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA724738 Filing date: 02/03/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91214199 Party Plaintiff Dave Brock Correspondence MICHELLE C BURKE Address MCDERMOTT WILL & EMERY LLP 227 W MONROE STREET SUITE 4400 CHICAGO, IL 60606-5096 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], cgor- [email protected] Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name Clark T. Gordon Filer's e-mail [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], cgor- [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Clark T. Gordon/ Date 02/03/2016 Attachments Opposition No. 91214199 Notice of Reliance.pdf(5528880 bytes ) I IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In re Application Serial No. 85776225 Mark: NIK TURNER'S HAWKWIND ) DAVE BROCK ) ) Opposer, ) ) Opposition No. 9I2I4I99 v. ) ) NICHOLAS TURNER ) ) Applicant. ) NOTICE OF RELIANCE Opposer Dave Brock, by and through his attorney, hereby submits this Notice of Reliance pursuant to Trademark Rule §2.I22(e). Opposer relies upon the following published articles to the extent they (I) establish the existence of a Hawkwind fan base in the United Sates, (2) establish that Dave Brock has continuously been the leader of Hawkwind since he founded the group over 45 years ago, (3) establish that Nik Turner is damaging the Hawkwind brand by using the mark NIK TURNER'S HAWK WIND, (4) or otherwise support the arguments put forth by Opposer in this Opposition. -

Muddy Fun Hits Sticking Point

C M Y K www.newssun.com Friday’s Doggy Football Scores dress-up Booker . 36 Costume Avon Park . 34 EWS UN tips for Overtime NHighlands County’s Hometown-S Newspaper Since 1927 your pets Scary Armed robbery PAGE 12B Clewiston . 35 scenes Lake Placid . 7 Deputies: Man More TV robbed friend at shows gunpoint, then Winter Haven . 45 going for Sebring . 7 frights asked him for a light PAGE 14B PAGE 2A DETAILS IN SPORTS, 1B Sunday, October 23, 2011 www.newssun.com Volume 92/Number 125 | 75 cents Forecast Muddy Handley Partly sunny and replacing pleasant High Low fun hits Carlson 81 60 Complete Forecast Local builder will PAGE 14A sticking serve out rest of term Online ࡗ Photo, page 2A y photo By ED BALDRIDGE Courtes [email protected] point TALLAHASSEE — After almost a year of no representation, citizens in District 3 now have a new county commissioner. Question: Should the Gov. Rick Scott appointed local con- state reject a federal tractor William “Ron” Handley Thursday early learning grant if to fill the seat left empty when Jeffery D. there are strings Carlson was removed in November of attached? 2010. Handley will serve the remainder of Carlson’s term, which expires on Nov. 20, Yes 2012. According to the press release from % Gov. Scott’s office, Handley, 56, of 72.9 Sebring, has “owned and operated Homes by Handley Inc. since 1990 and W.R. Handley Construction Company from 1984 to 1990.” No See HANDLEY, page 5A 27.1% Council wants Total votes: 48 Next question: to discuss Does the county need a place where people News-Sun photo by SCOTT DRESSEL Gabe White, whose truck is shown above, talks about the proposed Saddleridge outdoor recreation Rowan issue can legally ride ATVs area, which will feature mud bogs, ATV trails, camping, fishing and more if it clears legal hurdles. -

Volume 7 | Issue 1 | Fall 2017

ARIZONA STATE SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 7 FALL 2017 ISSUE 1 SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR COLLEGE OF LAW ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY 111 EAST TAYLOR STREET PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85004 ABOUT THE JOURNAL The Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal is edited by law students of the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University. As one of the leading sports and entertainment law journals in the United States, the Journal infuses legal scholarship and practice with new ideas to address today’s most complex sports and entertainment legal challenges. The Journal is dedicated to providing the academic community, the sports and entertainment industries, and the legal profession with scholarly analysis, research, and debate concerning the developing fields of sports and entertainment law. The Journal also seeks to strengthen the legal writing skills and expertise of its members. The Journal is supported by the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law and the Sports Law and Business Program at Arizona State University. WEBSITE: www.asuselj.org. SUBSCRIPTIONS: To order print copies of the current issue or previous issues, please visit Amazon.com or visit the Journal’s website. SUBMISSIONS: Please visit the Journal’s website for submissions guidance. SPONSORSHIP: Individuals and organizations interested in sponsoring the Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal should contact the current Editor-in-Chief at the Journal’s website. COPYRIGHT ©: 2017–2018 by Arizona State Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. All rights -

Jacobs Becomes OC Mayor Teresa Jacobs’ Victory in the Mayoral Election Expands with Support from Her Fellow Commissioner, Bill Segal

PAIGE 2 NEWS 3 OPINION 15 FEATURES 18 SPORTS 20 OCT. 06, 2010 Official Student Media of Valencia Community College 1 Republican Rick Republicans take Scott elected as the house Florida Governor Novmber 3, 2010 VOLUME 8 • ISSUE 13 VALENCIAVOICE.COM Official Student Media of Valencia Community College Read on page 5 Read on Page 3 Jacobs becomes OC Mayor Teresa Jacobs’ victory in the mayoral election expands with support from her fellow commissioner, Bill Segal By David Damron and campaign-finance rules. The Orlando Sentinel, Fla. Segal, who raised $1 million overall and dou- bled Jacobs’ donation haul, was an early favor- Embracing her populist message, voters Tues- ite. The Winter Park Democrat’s resume included day gave Teresa Jacobs an overwhelming victory three decades in business and heavy involvement over business-backed Bill Segal in the race for Or- in helping charities. ange County mayor. Segal ran largely on his business acumen and, Jacobs won nearly 68 percent of the vote to 32 per- if elected, he promised to enact a modest proper- cent for Segal, who called Jacobs to congratulate her ty-tax cut and breaks for businesses who created on the victory less than an hour after the polls closed. high-paying jobs. “The citizens of Orange County desperately want Segal, 61, who gave up the last two years of his good, honest government, and they want to believe,” second commission term, was the first to enter Jacobs said. “This campaign gave them a reason to what ended up as a four-way primary that in- believe that we can do a better job, and we will.” cluded Commissioner Linda Stewart and busi- C/O Facebook Segal quickly offered Jacobs his support as she nessman Matthew Falconer. -

Wizard World Comic Con Chicago 2013 Programming

Wizard World Comic Con Chicago 2013 Programming August 8th – August 11th, 2013 ROOM LOCATIONS / SECOND FLOOR ROOM 21 – GAMING ROOM ROOM 24 – GENERAL PROGRAMMING ROOM 34 – GENERAL PROGRAMMING ROOM 41 – GENERAL PROGRAMMING ROOM 42 – GENERAL PROGRAMMING ROOM 49 – FRANK FRAZETTA MUSEUM ROOM 50 – GENERAL PROGRAMMING ROOM 52 – SPEED DATING ROOM 60 – MEET & GREET / PORTFOLIO REVIEW THURSDAY, AUGUST 8th 3:00 - 8:00PM THE ART OF FRANK FRAZETTA Robert Rodriguez curates this installation of original Frank Frazetta masterwork paintings including several from Rodriguez’s personal collection. This is a rare up close look at the famous creations from the most influential American artist of the 20th century. A donation to the museum allows access to this rare, unprecedented event. (ROOM 49) 4:00 – 4:45PM FROM THE MICROSCOPE TO THE BIG SCREEN: CREEPY CRAWLIES IN POP CULTURE We enjoy so many movies and stories inspired by insects and other creepy crawlies. Join John Leavengood, insect taxonomist and evolutionary biologist, to learn how things like the monsters from the “Alien" movie series, Starship Troopers, Spider-Man, The Tick, Ant-Man and giant monstrous insects compare to actual insects and their almost supernatural abilities, weird appearances and strange behavior. (ROOM 34) 4:00 – 4:45PM THE WIZARD WORLD FILM FESTIVAL: COMING SOON TO A CON NEAR YOU Are you an independent filmmaker or a fan of independent films? Most indie films run the film festival circuit to promote and hopefully find distribution for their films. Wizard World is proud to announce the Wizard World Film Festival, now accepting submissions for its final three events of 2013, beginning with the Wizard World Ohio Comic Con, Sept. -

Paranormal Tourism Study of Economics and Public Policy

PARANORMAL TOURISM STUDY OF ECONOMICS AND PUBLIC POLICY by EVERETT DRAKE HAYNES A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF REGIONAL AND COMMUNITY PLANNING Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional & Community Planning College of Architecture, Planning, & Design KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Katherine Nesse Copyright EVERETT DRAKE HAYNES 2016 Abstract Humanity’s belief in the paranormal has shaped cultures, folklore, religion, and influences the arts, customs, politics, and economics. In the modern era, paranormal belief continues to capture public interest, often fueled by popular entertainment and media. With belief in the paranormal on the rise, so are the social and economic implications. Literature and data also shows that paranormal niche tourism is becoming increasingly popular and have an effect on the tourism sector, yet it is poorly understood. The purpose of this study is to ask, “how does paranormal niche tourism affect and relate to local economics and public policy?” New Orleans serves as the subject city due to its rich paranormal history and folklore and thriving tourism economy. I divided data collection into two main phases: 1) surveying paranormal tourists and 2) surveying and interviewing paranormal-related businesses including tour companies, retail and services, and hotels. I distributed online surveys to paranormal tourists to collect data pertaining to demographics, education, employment, belief, belief influencers, travel habits, and costs. In addition, I conducted online surveys and personal interviews with businesses relating to paranormal tourism in regards to business model, marketing, revenue, employment, local community impact, and public policy impacts.