Improving Soldier and Unit Effectiveness with the Stryker Brigade Combat Team Warfighters’ Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veteran Reserve Corps (VRC), 1863–1865

National Archives and Records Administration 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20408-0001 Veteran Reserve Corps (VRC), 1863–1865 War Department General Orders No. 105, issued by the Adjutant General’s Office on April 28, 1863, authorized the creation of the Veteran Reserve Corps (VRC) originally called the Invalid Corps. The Corps consisted of companies and battalions made up of officers and enlisted men unfit for active field service because of wounds or disease contracted in the line of duty, but still capable of performing garrison duty officers and enlisted men in service and on the Army rolls otherwise absent from duty and in hospitals, in convalescent camps, or otherwise under the control of medical officials, but capable of serving as cooks, clerks, orderlies, and guards at hospitals and other public buildings officers and enlisted men honorably discharged because of wounds or disease and who wanted to reenter the service The Invalid Corps was renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps on March 18, 1864. Confusion with the damaged goods stamp “I.C.” (inspected-condemned) affected volunteer morale. Compiled Military Service Records (CMSRs) In the 1890s, the Department of War used numerous sources, such as muster rolls, descriptive rolls, and pay rolls to create compiled military service records. These records generally show when a soldier joined a unit and if he was present when the unit was mustered. Veteran Reserve Corps Service ___M636, Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Swerved in the Military Records of the Veteran Reserve Corps. 44 rolls. DP. Arranged alphabetically by the soldier’s surname. -

Introduction to Army Leadership

8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 2 Leadership Track Section 1 INTRODUCTION TO ARMY LEADERSHIP Key Points 1 What Is Leadership? 2 The Be, Know, Do Leadership Philosophy 3 Levels of Army Leadership 4 Leadership Versus Management 5 The Cadet Command Leadership Development Program e All my life, both as a soldier and as an educator, I have been engaged in a search for a mysterious intangible. All nations seek it constantly because it is the key to greatness — sometimes to survival. That intangible is the electric and elusive quality known as leadership. GEN Mark Clark 8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 3 Introduction to Army Leadership ■ 3 Introduction As a junior officer in the US Army, you must develop and exhibit character—a combination of values and attributes that enables you to see what to do, decide to do it, and influence others to follow. You must be competent in the knowledge and skills required to do your job effectively. And you must take the proper action to accomplish your mission based on what your character tells you is ethically right and appropriate. This philosophy of Be, Know, Do forms the foundation of all that will follow in your career as an officer and leader. The Be, Know, Do philosophy applies to all Soldiers, no matter what Army branch, rank, background, or gender. SGT Leigh Ann Hester, a National Guard military police officer, proved this in Iraq and became the first female Soldier to win the Silver Star since World War II. Silver Star Leadership SGT Leigh Ann Hester of the 617th Military Police Company, a National Guard unit out of Richmond, Ky., received the Silver Star, along with two other members of her unit, for their actions during an enemy ambush on their convoy. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

Service Values of the Armed Forces

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER INTRODUCTION The Meaning of the Commission As an officer in the Armed Forces of the United States, you are a citizen-soldier, a warrior in the profession of arms, a member of a skilled profession, an unwavering defender of the Constitution and a servant of the nation. A leader of character, you accept unmitigated personal responsibility and accountability to duty, for your actions and those of your subordinates. You lead your service and defend the nation in seamless union with officers of all services. In so doing, you willingly take your place in an ancient and honorable calling, obligated equally to those who have gone before you, those you walk among, and those who will follow. “There is no greater demonstration of the trust of the Republic than in its expression and bestowal of an officer’s commission.”1 This trust involves the majesty of the nation’s authority in matters involving the lives and deaths of its citizens. That this particular trust most often is first directed on men and women of no particular experience in life, leadership, or war, elevates the act to a supreme occasion of faith as well. Accepting an officer’s commission in the armed forces is a weighty matter, carrying a corresponding burden of practical and moral responsibility. The officer must live up to this responsibility each day he or she serves. In 1950, the Office of the Secretary of Defense published a small handbook with a dark blue cover titled simply, The Armed Forces Officer.2 Journalist-historian Brigadier General (Army Reserve) S. -

Modernizing Soldier Lethality by Kimball Johnson

Researchers are currently developing the Human-interest Image Detector, a passive brain monitoring system that attempts to detect operator interest in visual scenes. (U.S. Army photo) Modernizing Soldier Lethality By Kimball Johnson odernization" is a concept older than the "We set six priorities: long-range precision fires, invention of repeating rifles and revolvers. next-generation combat vehicles, future vertical lift, Its definition includes the drive to conduct network communications, air and missile defense, and Mresearch and field new technology designed to defend Soldier lethality, spanning all the fundamentals of shoot, the lives of Soldiers and overcome threats on and off the movement, communicate, sustain and protect," McCar- battlefield. thy said.1 With modernization comes the underlying temptation to wonder if future technological advancements in offensive Center for Adaptive Soldier Technologies capabilities by Army scientists could potentially replace Improving Soldier lethality is an ongoing project at Soldiers in the field. Noncommissioned officers, however, ARL's Center for Adaptive Soldier Technologies, located have enough experience with new gear to know technology at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. Research topics can never replace the human factor. Imparting hard-won on their website include cybernetics, "Brain Computer wisdom to their Soldiers, as well as lessons learned from Interface," "The Human Interest Detector," and "The fielding new equipment, will remain the NCO's role. Human Variability Project." Addison Bohannon, a BCI bench scientist, and math- The Army Research Laboratory's Goals ematician with ARL said CAST's purpose is to make new Ryan D. McCarthy, the undersecretary of the Army, technology adaptable to Soldiers' needs. -

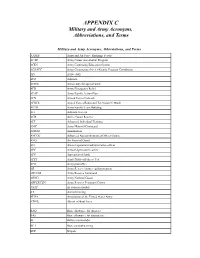

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

FM 21-100 Soldier's Handbook

21-100 MH! WAR DEPARTMENT BASIC FIELD MANUAL SOLDIER©S HANDBOOK 21-100 BASIC FIELD MANUAL SOLDIER©S HANDBOOK Prepared under direction of the Chief of Staff UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. - Price 35 cents WAR DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, December 11, 1940. FM 21-100, Soldier©s Handbook, is published for the infor mation and guidance of all concerned. Its purpose is to give the newly enrolled member of the United States Army a con venient and compact source of basic military information and thus to aid him to perform his duties more efficiently. [A. G. 062.11 (10-21-40).] BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF WAR: G. C. MARSHALL, Chief of Staff. OFFICIAL : E. S. ADAMS, Major General, The Adjutant General. n FOREWORD You are now a member of the Army of the United States. That Army is made up of free citizens chosen from among a free people. The American people of their own will, and through the men they have elected to represent them in Con gress, have determined that the free institutions of this coun try will continue to exist. They have declared that, if necessary, we will defend our right to live in our own American way and continue to enjoy the benefits and privileges which are granted to the citizens of no other nation. It is upon you, and the many thousands of your comrades now in the mili tary service, that our country has placed its confident faith that this defense will succeed should it ever be challenged. -

Military Service Records at the National Archives Military Service Records at the National Archives

R E F E R E N C E I N F O R M A T I O N P A P E R 1 0 9 Military Service Records at the national archives Military Service Records at the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 1 0 9 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Trevor K. Plante Revised 2009 Plante, Trevor K. Military service records at the National Archives, Washington, DC / compiled by Trevor K. Plante.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, revised 2009. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; 109) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration —Catalogs. 2. United States — Armed Forces — History — Sources. 3. United States — History, Military — Sources. I. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. II. Title. Front cover images: Bottom: Members of Company G, 30th U.S. Volunteer Infantry, at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, August 1899. The regiment arrived in Manila at the end of October to take part in the Philippine Insurrection. (111SC98361) Background: Fitzhugh Lee’s oath of allegiance for amnesty and pardon following the Civil War. Lee was Robert E. Lee’s nephew and went on to serve in the Spanish American War as a major general of the United States Volunteers. (RG 94) Top left: Group of soldiers from the 71st New York Infantry Regiment in camp in 1861. (111B90) Top middle: Compiled military service record envelope for John A. McIlhenny who served with the Rough Riders during the SpanishAmerican War. He was the son of Edmund McIlhenny, inventor of Tabasco sauce. -

Assessing the Needs of Soldiers and Their Families

Today’s Soldier Assessing the Needs of Soldiers and Their Families Carra S. Sims, Thomas E. Trail, Emily K. Chen, Laura L. Miller C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1893 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9784-2 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover photos (clockwise): Staff Sgt. Tomora Nance, 3rd Calvalry Regiment Public Affairs Office/DVIDS; Sgt. Kalie Jones, U.S. Army/U.S. Department of Defense; Mr. Pak, Chin U./U.S. Army; Visual Information Specialist Jason Johnston, U.S. Army/DVIDS Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. -

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M

THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce The Armed Forces Officer THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER by Richard M. Swain and Albert C. Pierce National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. 2017 Published in the United States by National Defense University Press. Portions of this book may be quoted or reprinted without permission, provided that a standard source credit line is included. NDU Press would appreciate a courtesy copy of reprints or reviews. Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record of this publication may be found at the Library of Congress. Book design by Jessica Craney, U.S. Government Printing Office, Creative Services Division Published by National Defense University Press 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64) Suite 2500 Fort Lesley J. McNair Washington, DC 20319 U.S. GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-16-093758-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Contents FOREWORD by General Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ...............................................................................ix PREFACE by Major General Frederick M. -

GAO-21-361, Military Vehicles: Army and Marine Corps Should Take

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters July 2021 MILITARY VEHICLES Army and Marine Corps Should Take Additional Actions to Mitigate and Prevent Training Accidents GAO-21-361 July 2021 MILITARY VEHICLES Army and Marine Corps Should Take Additional Actions to Mitigate and Prevent Training Accidents Highlights of GAO-21-361, a report to congressional requesters Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Tactical vehicles are used to train The number of serious accidents involving Army and Marine Corps tactical military personnel and to achieve a vehicles, such as tanks and trucks, and the number of resulting deaths, variety of missions. Both the Army and fluctuated from fiscal years 2010 through 2019 (see figure). Driver Marine Corps have experienced inattentiveness, lapses in supervision, and lack of training were among the most tactical vehicle accidents that resulted common causes of these accidents, according to GAO analysis of Army and in deaths of military personnel during Marine Corps data. non-combat scenarios. GAO was asked to review issues Number of Army and Marine Corps Class A and B Tactical Vehicle Accidents and Resulting Military Deaths, Fiscal Years 2010 through 2019 related to the Army’s and Marine Corps’ use of tactical vehicles. Among other things, this report examines (1) trends from fiscal years 2010 through 2019 in reported Army and Marine Corps tactical vehicle accidents, deaths, and reported causes; and evaluates the extent to which the Army and Marine Corps have (2) taken steps to mitigate and prevent accidents during tactical vehicle operations; and (3) provided personnel with training to build the skills and experience needed to drive tactical vehicles. -

US MILITARY CUSTOMS and COURTESIES Key Points

8420010_OT2_p128-135 8/15/08 2:38 PM Page 128 Section 2 US MILITARY CUSTOMS AND COURTESIES Key Points 1 Military Customs and Courtesies: Signs of Honor and Respect 2 Courtesies to Colors, Music, and Individuals Officership Track 3 Military Customs: Rank and Saluting 4 Reporting to a Superior Officer e The courtesy of the salute is encumbent on all military personnel, whether in garrison or in public places, in uniform or civilian clothes. The exchange of salutes in public places impresses the public with our professional sincerity, and stamps officers and enlisted men as members of the Governmental instrumentality which ensures law and order and the preservation of the nation. GEN Hugh Drum 8420010_OT2_p128-135 8/15/08 2:38 PM Page 129 US Military Customs and Courtesies ■ 129 Introduction A custom is a social convention stemming from tradition and enforced as an unwritten military courtesy law. A courtesy is a respectful behavior often linked to a custom. A military courtesy is such behavior extended to a person or thing that honors them in some way. the respect and honor Military customs and courtesies define the profession of arms. When you shown to military traditions, practices, display military customs and courtesies in various situations, you demonstrate to symbols, and individuals yourself and others your commitment to duty, honor, and country. As a Cadet and future Army leader, you must recognize that military customs and courtesies are your constant means of showing that the standard of conduct for officers military customs and Soldiers is high and disciplined, is based on a code akin to chivalry, and is universal throughout the profession of arms.