Understanding the Military: the Institution, the Culture, and the People, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROMOTION REQUIREMENTS for CAP Members

PROMOTION REQUIREMENTS for CAP Members BY JOHN W. TALBOTT, Lt Col, CAP NEBRASKA WING Developed on 03/15/02 Update on 26 February 2006 AIR FORCE OFFICER RANKS Colonel (O-6) (Col) Second Lieutenant (O-1) (2nd Lt) st Brigadier General (O-7) (Brig Gen) First Lieutenant (O-2) (1 Lt) Captain (O-3) (Capt) Major General (08) (Maj Gen) Major (O-4) (Maj) Army Air Corps Lieutenant Colonel (O-5) (Lt Col) AIR FORCE NCO RANKS Chief Master Sergeant (E-9) (CMsgt) Senior Master Sergeant (E-8) (SMsgt) Master Sergeant (E-7) (Msgt) Technical Sergeant (E-6) (Tsgt) Staff Sergeant (E-5) (Ssgt) CAP Flight Officers Rank Flight Officer: Technical Flight Officer Senior Flight Officer NOTE: The following is a compilation of CAP Regulation 50-17 and CAP 35-5. It is provided as a quick way of evaluating the promotion and training requirements for CAP members, and is not to be treated as an authoritative document, but instead it is provided to assist CAP members in understanding how the two different regulations are inter-related. Since regulations change from time to time, it is recommended that an individual using this document consult the actual regulations when an actual promotion is being evaluated or submitted. Individual section of the pertinent regulations are included, and marked. John W. Talbott, Lt Col, CAP The following are the requirements for various specialty tracks. (Example: promotion to the various ranks for senior Personnel, Cadet Programs, etc.) members in Civil Air Patrol (CAP): For promotion to SFO, one needs to complete 18 months as a TFO, (See CAPR 35-5 for further details.) and have completed level 2: (Attend Squadron Leadership School, complete Initially, all Civil Air Patrol the CAP Officer course ECI Course 13 members who are 18 years or older are or military equivalent, and completes the considered senior members, (with no requirements for a Technician rating in a senior member rank worn), when they specialty track (this is completed for join Civil Air Patrol. -

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII

Los Veteranos—Latinos in WWII Over 500,000 Latinos (including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans) served in WWII. Exact numbers are difficult because, with the exception of the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico, Latinos were not segregated into separate units, as African Americans were. When war was declared on December 8, 1941, thousands of Latinos were among those that rushed to enlist. Latinos served with distinction throughout Europe, in the Pacific Theater, North Africa, the Aleutians and the Mediterranean. Among other honors earned, thirteen Medals of Honor were awarded to Latinos for service during WWII. In the Pacific Theater, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, of which a large percentage was Latino and Native American, fought in New Guinea and the Philippines. They so impressed General MacArthur that he called them “the greatest fighting combat team ever deployed in battle.” Latino soldiers were of particular aid in the defense of the Philippines. Their fluency in Spanish was invaluable when serving with Spanish speaking Filipinos. These same soldiers were part of the infamous “Bataan Death March.” On Saipan, Marine PFC Guy Gabaldon, a Mexican-American from East Los Angeles who had learned Japanese in his ethnically diverse neighborhood, captured 1,500 Japanese soldiers, earning him the nickname, the “Pied Piper of Saipan.” In the European Theater, Latino soldiers from the 36th Infantry Division from Texas were among the first soldiers to land on Italian soil and suffered heavy casualties crossing the Rapido River at Cassino. The 88th Infantry Division (with draftees from Southwestern states) was ranked in the top 10 for combat effectiveness. -

Fm 6-02 Signal Support to Operations

FM 6-02 SIGNAL SUPPORT TO OPERATIONS SEPTEMBER 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes FM 6-02, dated 22 January 2014. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil/) and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *FM 6-02 Field Manual Headquarters No. 6-02 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 13 September 2019 Signal Support to Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 OVERVIEW OF SIGNAL SUPPORT ........................................................................ 1-1 Section I – The Operational Environment ............................................................. 1-1 Challenges for Army Signal Support ......................................................................... 1-1 Operational Environment Overview ........................................................................... 1-1 Information Environment ........................................................................................... 1-2 Trends ........................................................................................................................ 1-3 Threat Effects on Signal Support ............................................................................. -

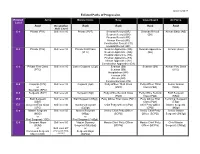

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14

City of Winder Job Description: Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14 EEO Function: Pay Grade: PD-6 EEO Category: Professional Status: Non-Exempt Pay Type: Hourly Position Number: 6346 I. Chain of Command/ Reports To Police Sergeant or through the Chain of Command to the Chief of Police II. Job Summary The functions of a Police Corporal are similar to that of a Police Officer with additional duties as an assistant supervisor or as a shift commander in the absence of a Sergeant. While incumbents are normally assigned to a specific geographic area for patrol, all functional areas of the law enforcement field, including investigation, administration, and training are included. A Police Corporal is also expected to perform field duties relating to response to emergencies, general and directed patrol, investigation of crimes and other non- criminal incidents, traffic enforcement and control, assisting in crime prevention activities, and other law enforcement services and duties as required. A significant degree of initiative, independent judgment, and discretion is required of incumbents to develop, maintain, and successfully perform supervisory tasks in a community oriented, problem solving approach to policing. III. Essential Duties and Functions • Follow and promote Policy & Procedures of the City of Winder. • Ensures that laws and ordinances are enforced and that the public peace and safety is maintained. • Responds to and resolves difficult and sensitive citizen inquiries and complaints. • Ensures the compliance of quality customer services to the public and internal City departments and employees. • Develops and maintains effective working relationships with the community. • Ensures that the department offers and maintains an effective and positive Community Oriented Policing philosophy for the purpose of maintaining the highest possible credibility level within the City. -

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, the Citadel

Staff Sergeant Ricky Hart Assistant Marine Officer Instructor NROTC Unit, The Citadel Staff Sergeant Hart was born in Beaufort, South Carolina on 9 September, 1987. He enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2005 and attended recruit training with Fox Company, 2nd Recruit Training Battalion, Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, where he graduated as a meritorious Private First Class. Upon completion of recruit training in February of 2006, Staff Sergeant Hart reported to Marine Combat Training Battalion, Golf Company, and graduated in March of 2006. Staff Sergeant Hart was transferred to NAS Pensacola, where he attended Aviation Warfare Apprentice Training and Avionics Technician Intermediate Level Course, Class A1. While stationed at NAS Pensacola Staff Sergeant Hart was promoted to the rank of Lance Corporal and graduated his MOS at the top of his class. In October 2006, he was sent to his follow on MOS school aboard Keesler Air Force Base, Biloxi Mississippi. It was here Staff Sergeant Hart would learn his primary MOS of Precision Measurement Equipment (PME) Technician by completing General Purpose Electronic Test Equipment Repair and Calibration where he graduated at the top of his class. He also completed Intermediate Level Calibration of Physical/Dimensional and Measuring Systems school. In March of 2007, Staff Sergeant Hart received orders to his first duty station aboard MCAS New River, NC where he served as a Precision Measurement Equipment Technician within the MALS-29 Calibration Laboratory. In 2009 he was meritoriously promoted to the rank of Corporal and continued to serve with MALS-29. In August 2010, Staff Sergeant Hart re-enlisted in the Marine Corps and was transferred to MCAS Cherry Point, NC where he was assigned to MALS-14 and served as the Issue and Receive NCOIC for the Calibration Laboratory. -

Introduction to Army Leadership

8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 2 Leadership Track Section 1 INTRODUCTION TO ARMY LEADERSHIP Key Points 1 What Is Leadership? 2 The Be, Know, Do Leadership Philosophy 3 Levels of Army Leadership 4 Leadership Versus Management 5 The Cadet Command Leadership Development Program e All my life, both as a soldier and as an educator, I have been engaged in a search for a mysterious intangible. All nations seek it constantly because it is the key to greatness — sometimes to survival. That intangible is the electric and elusive quality known as leadership. GEN Mark Clark 8420010_LT1_p002-015 8/14/08 1:31 PM Page 3 Introduction to Army Leadership ■ 3 Introduction As a junior officer in the US Army, you must develop and exhibit character—a combination of values and attributes that enables you to see what to do, decide to do it, and influence others to follow. You must be competent in the knowledge and skills required to do your job effectively. And you must take the proper action to accomplish your mission based on what your character tells you is ethically right and appropriate. This philosophy of Be, Know, Do forms the foundation of all that will follow in your career as an officer and leader. The Be, Know, Do philosophy applies to all Soldiers, no matter what Army branch, rank, background, or gender. SGT Leigh Ann Hester, a National Guard military police officer, proved this in Iraq and became the first female Soldier to win the Silver Star since World War II. Silver Star Leadership SGT Leigh Ann Hester of the 617th Military Police Company, a National Guard unit out of Richmond, Ky., received the Silver Star, along with two other members of her unit, for their actions during an enemy ambush on their convoy. -

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack

Combatant Status and Computer Network Attack * SEAN WATTS Introduction .......................................................................................... 392 I. State Capacity for Computer Network Attacks ......................... 397 A. Anatomy of a Computer Network Attack ....................... 399 1. CNA Intelligence Operations ............................... 399 2. CNA Acquisition and Weapon Design ................. 401 3. CNA Execution .................................................... 403 B. State Computer Network Attack Capabilites and Staffing ............................................................................ 405 C. United States’ Government Organization for Computer Network Attack .............................................. 407 II. The Geneva Tradition and Combatant Immunity ...................... 411 A. The “Current” Legal Framework..................................... 412 1. Civilian Status ...................................................... 414 2. Combatant Status .................................................. 415 3. Legal Implications of Status ................................. 420 B. Existing Legal Assessments and Scholarship.................. 424 C. Implications for Existing Computer Network Attack Organization .................................................................... 427 III. Departing from the Geneva Combatant Status Regime ............ 430 A. Interpretive Considerations ............................................. 431 * Assistant Professor, Creighton University Law School; Professor, -

Military Historical Society of Minnesota

The 34th “Red Bull” Infantry Division 1917-2010 Organization and World War One The 34th Infantry Division was created from National Guard troops of Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas and Nebraska in late summer 1917, four months after the US entered World War One. Training was conducted at Camp Cody, near Deming, New Mexico (pop. 3,000). Dusty wind squalls swirled daily through the area, giving the new division a nickname: the “Sandstorm Division.” As the men arrived at Camp Cody other enlistees from the Midwest and Southwest joined them. Many of the Guardsmen had been together a year earlier at Camp Llano Grande, near Mercedes, Texas, on the Mexican border. Training went well, and the officers and men waited anxiously throughout the long fall and winter of 1917-18 for orders to ship for France. Their anticipation turned to anger and frustration, however, when word was received that spring that the 34th had been chosen to become a replacement division. Companies, batteries and regiments, which had developed esprit de corps and cohesion, were broken up, and within two months nearly all personnel were reassigned to other commands in France. Reduced to a skeleton of cadre NCOs and officers, the 34th remained at Camp Cody just long enough for new draftees to refill its ranks. The reconstituted division then went to France, but by the time it arrived in October 1918, it was too late to see action. The war ended the following month. Between Wars After World War One, the 34th was reorganized with National Guardsmen from Iowa, Minnesota and South Dakota. -

Noncombatant Immunity and War-Profiteering

In Oxford Handbook of Ethics of War / Published 2017 / doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199943418.001.0001 Noncombatant Immunity and War-Profiteering Saba Bazargan Department of Philosophy UC San Diego Abstract The principle of noncombatant immunity prohibits warring parties from intentionally targeting noncombatants. I explicate the moral version of this view and its criticisms by reductive individualists; they argue that certain civilians on the unjust side are morally liable to be lethally targeted to forestall substantial contributions to that war. I then argue that reductivists are mistaken in thinking that causally contributing to an unjust war is a necessary condition for moral liability. Certain noncontributing civilians—notably, war-profiteers— can be morally liable to be lethally targeted. Thus, the principle of noncombatant immunity is mistaken as a moral (though not necessarily as a legal) doctrine, not just because some civilians contribute substantially, but because some unjustly enriched civilians culpably fail to discharge their restitutionary duties to those whose victimization made the unjust enrichment possible. Consequently, the moral criterion for lethal liability in war is even broader than reductive individualists have argued. 1 In Oxford Handbook of Ethics of War / Published 2017 / doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199943418.001.0001 1. Background 1.1. Noncombatant Immunity and the Combatant’s Privilege in International Law In Article 155 of what came to be known as the ‘Lieber Code’, written in 1866, Francis Lieber wrote ‘[a]ll enemies in regular war are divided into two general classes—that is to say, into combatants and noncombatants’. As a legal matter, this distinction does not map perfectly onto the distinction between members and nonmembers of an armed force. -

Fm 3-21.5 (Fm 22-5)

FM 3-21.5 (FM 22-5) HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JULY 2003 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. *FM 3-21.5(FM 22-5) FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 3-21.5 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, DC, 7 July 2003 DRILL AND CEREMONIES CONTENTS Page PREFACE........................................................................................................................ vii Part One. DRILL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. History................................................................................... 1-1 1-2. Military Music....................................................................... 1-2 CHAPTER 2. DRILL INSTRUCTIONS Section I. Instructional Methods ........................................................................ 2-1 2-1. Explanation............................................................................ 2-1 2-2. Demonstration........................................................................ 2-2 2-3. Practice................................................................................... 2-6 Section II. Instructional Techniques.................................................................... 2-6 2-4. Formations ............................................................................. 2-6 2-5. Instructors.............................................................................. 2-8 2-6. Cadence Counting.................................................................. 2-8 CHAPTER 3. COMMANDS AND THE COMMAND VOICE Section I. Commands ........................................................................................