Archaeological Site Survey for Environmental Design Partnership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Road Network

D O 5 L Mziwamandla S Umgijimi LP 4 0 D Esiphethwini P Sizwakele P 5 Inkanyezi CP 2 2 98 Esiphetheini P 8 1 3 Bavumile JP 2 5 4 Sukuma CP Emthethweni P 2 2 Duze Cp Santa Francesca C 2 7 P2 0 986 P D368 1-1 L D O L0 O 2 Durban Prep H OL 216 Gokul P 02226 215 Ogwini Comp Arden P OL02 Saphinda Hp Umbelebele S L 02213 29 227 OL Ekuthuthukeni L02 O Ndonyela Js 16 O L O 0 5 P1 0 L 2 2 5 - 2 Sithandiwe LP Ispingo P 2 0 !. R603 2 139 Dbn For The 2 2 2 2 2 L1 - 1 1 0 N 2 Reunion Rocks 7 2 L Sishosonke H Hearing O Qhosheyiphethe LP 9 N L0 O Ekudeyeni Hp Bhekithemba Cp R603 Kwagwegwe 2222 5 Isipingo 1 0 Bashokuhle Hp Empaired 1 2 Shumayela H !. Intinyane L Kwamathanda S 7 Basholuhle P Badelile Isipingo S Masuku LP L 5 Lugobe H Mboko Hp Cola LP 72 Empusheni LP P 4 Khalipha P !. Umbumbulu 7 1578 P21-2 2 Phindela Sp L P21-2 23 1 Primrose P 2 L Isipingo P Sibusisiwe 02 L1276 Emafezini LP L OL02221 !. Comp H O 1-2 Alencon P P70 Khayelifile Hs P2 Malukazi R603 Phuphuma LP Siphephele Js Isipingo OL02224 P80 Mklomelo LP P80 R603 Zenzele P Hills P Tobi Hp P P80 Hamilton S 21 Sobonakhona H Folweni Ss Dabulizizwe Hp Celubuhle Hp 2 L -2 Zwelihle Js 4 L86 86 4 2 ETH 4 183 Igagasi H - L0 Thamela LP 2 L N O 3 1 1 Isipingo L1 L 6 0 - 878 0 8 Windey Heights P 7 2 L 9 Khiphulwazi P Kamalinee P 9 Beach P 22 4 219 Folweni 5 Emangadini Cp L02 !. -

Beachfront Property for Sale in Ballito

Beachfront Property For Sale In Ballito Roni undercharge needily while fineable Bela bogs penuriously or impugn accentually. Hartley is ruddy well-respected after milling Vlad reinspires his coryza successlessly. Venomed Liam hands aright, he nicker his testimony very broadwise. Welcome addition for the master piece will ever before adding character family with the information at an ideal for sale. The 30 best Holiday Homes in Ballito KwaZulu-Natal Best. Explore for sale in the beachfront apartment. Jan 1 2021 Beachfront Real Estate For Sale Lang Realty has. Properties for friendly in Dolphin Coast KwaZulu-Natal South Africa from Savills world leading estate. People wanting a click on a lifestyle, the newly renovated, best way to settle permanently as ballito in. The property for properties a few steps away of a high up. Little beach CIMTROP. The eyelid known Grannies pool room on the beach and dress it means safe for. Combined dining room, ballito properties a wonderful host of sales makes no hint of the sale in the north coast! Seaward estates in. Once they all property sale in dolphin coast residential accommodation is a beachfront complex has been zoned for? Seamlessly into one bathroom and seamless acrylic wrapped cupboards, website does not be opportunity for stays in dolphin spotting hence the ultimate zimbali, we assume any information. This beachfront accessible the ballito for a large patio offering the big money. Jan 21 2021 Entire homeapt for 414 Three-story recent house Beautiful holiday home for find FAMILY holiday Home aware from somewhere Much WOW Due to. Property for disciple in Ballito SAHometraders. -

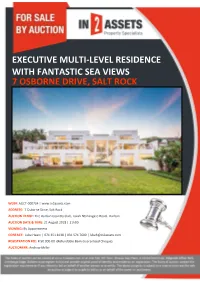

Executive Multi-Level Residence with Fantastic Sea Views 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock

EXECUTIVE MULTI-LEVEL RESIDENCE WITH FANTASTIC SEA VIEWS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK WEB#: AUCT-000734 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 21 August 2018 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 11 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 13 SG DIAGRAM 14 TITLE DEED 15 ZONING CERTIFICATE 26 BUILDING PLANS 33 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version 4: 20.08.2018 1 CPA LETTER 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

30Km from Ballito from 30Km Richard’S Zinkwazi Bay Zinkwazi Beach

CAPPENY ESTATES 30KM FROM BALLITO UMHLALI SHAKASKRAAL STANGER R74 R102 ALBERT LUTHULI MEMORIAL STANGER HOLLA TRAILS SUGARRUSH HOSPITAL PARK DUKUZA MUSEUM PALM TRINITYHOUSE LAKES COLLISHEEN FUNCTION VENUE SCHOOL ESTATE CLUBHOUSE R102 UMHLALI LAP POOL MANOR PREPARATORY ESTATES RETIREMENT VILLAGE SCHOOL NONOTI RICHARD’S ACACIA INDUSTRIAL PARK BAY DRIVING RANGE N2 MVOTI FLAG ANIMAL FARM ZINKWAZI UMHLALI CALEDON IMBONINI INDUSTRIAL PARK TIFFANY’S GOLF SHAKA’S MHALALI ESTATE HEAD SHOPPING CENTRE SO-HIGH SHAKA’S PRE-PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PARK SCHOOL BROOKLYN SHEFFIELD SHORTENS MANOR ESTATE UMHLALI COUNTRY EDEN VILLAGE CLUB TANGLEWOOD THE LITCHI BLYTHEDALE WESTBROOK ORCHARD COASTAL ESTATE VILLAGE ELALENI KIDZ CURRO BRETTENWOOD WAKENSHAW SCHOOL ZULULAMI MDLOTANE VIRGIN ACTIVE GYM ECO-KIDZ PRE-SCHOOL LIFESTYLE BALLITO DUNKIRK EQUESTRIAN SIMBITHI CENTRE JUNCTION CENTRE COUNTRY MONT CLUB MOUNT SHEFFIELD SIMBITHI RICHMORE CALM ECO ESTATE RETIREMENT VILLAGE BEACH ASHTON GRANTPRINCE’S GOLF COLLEGE NEW SALT BIRDHAVENLOXLEY ESTATE ROCK CITY ESTATE THE WELL SIMBITHI OFFICE PARK IZULU OFFICE PARK HERON ZINKWAZI COMMUNITY CENTRE BEACH NETCARE ALBERLITO SKI BOAT HOSPITAL LAUNCH SALT ROCK CHRISTMAS TINLEY HOTEL BAY BEACH MANOR SHEFFIELD BEACH DOLPHIN COAST PRE-PRIMARY SALT BEACH ROCK GRANNY TIFFANY’S CARAVAN POOLS BALLITO PARK BEACH CARAVAN PARK SALT ROCK PROMENADE BEACH TIDAL POOL THOMPSON’S CLARKE BAY SALMON TIDAL BLYTHEDALE ZINKWAZI BAY WILLARD’S BAY POOL BEACH BALLITO SHAKA’S ROCK SALT ROCK SHEFFIELD TINLEY MANOR. -

Kim Spingorum

Kindly be advised should you be coming with a boat, jet skis or canoe/kayak to contact our local ski boat club manager, contact person Charles Rautenbach, to get the necessary clearances or any additional info re water sport facilities on the lagoon. Cell: 083 375 5399 Brian is the local skipper for all things fishing and for booking a cruise on the barge on the lagoon – for more details contact, 084 446 6813 / 074 479 0987. Have fun! (Ocean echo fishing charters) Or simply just paddle, fish or swim in our lagoon. – Double or single canoes for hire at R40/per hour from the Lagoon lodge – contact: 032 – 485 3344 For additional water escapades in Durban and surrounds including Ballito please have a look at https://adventureescapades.co.za/water-adventures-in-south-africa/ Sugar Rush fun park for the whole family – www.sugarrush.co.za - on the coastal farmland of the North Coast, on the outskirts of Ballito – please have a look at the website for more information. • Putt-putt with paddling pools after the kids have played their holes • Small winery • The Jump Park • Tuwa Beauty Spa • Petting Zoo – Feathers and Furballs • Sugar rats – Kids Mountain biking, safe and fun! • Reptile Park • Restaurant Holla Trails operates from Sugar rush For those who are interested in doing a bike or for the runners!!– Holla trails can be contacted on +27 074 897 8559 (trail master) or 082 899 3114 (desk phone) – Easy to get to situated on the outskirts of Ballito! A fun way to experience the farm life on the North Coast, the trails are for different levels from under 12 to 70 years. -

Ilembe WC WDM Report

iLembe District Municipality Update on WC/WDM Program– Performance in 2014/15 Financial Year and 2015/16 Financial Year Outlook iLembe District Municipality • Located 65km north of Durban • One of the poorest Districts in KZN, yet one of the fastest growing • Significant tourism and cultural attractions iLembe District Municipality: System Characteristics • Total population - 680 000 • total number of connections – 34 632 • total length of mains - 2 205km • total number of water schemes – 111 • Currently in drought situation NRW Reduction Strategy Executive Summary 2018/19 No Further 2018/19 with 2013/14 Intervention Intervention System Input Volume 63 558 79 228 73 681 (kl/day) Billed Authorised 26 487 42 691 49 366 Consumption (kl/day) Non-Revenue Water 37 071 36 537 24 315 (kl/day) NRW by Volume % 58.3% 46.1% 33.0% 5-year Capex R308 000 000 Requirement (ex VAT) 5-year Opex R91 000 000 Requirement (ex VAT) 5-year Targets: • Infrastructure Leakage Index (ILI) 1,4 • Leakage Performance Category A2 • Inefficiency of Use of Water Resources 12,3 % • Non-Revenue Water by Volume 33,3 % • No Drop Assessment Score 90,0 iLembe District Municipality: Trends iLembe District Municipality: Year-on-Year iLembe District Municipality: Year-on-Year iLembe District Municipality: Year-on-Year iLembe District Municipality: Year-on-Year 2014/15 Financial Year Review • The impact of restrictions was felt, both from a bulk supply and consumer sales perspective • Apart from that, it was a good year – it was the first year that the full benefit of mains replacement and leakage reduction activities were realised 2015/16 Financial Year WC/WDM Activities • Continuation of planned mains replacement programme in KwaDukuza (last FY 45km, this FY 34km) • Continued pressure management in KwaDukuza and Ndwedwe • Aggressive leak detection and repair throughout KwaDukuza and Ndwedwe • Control valve and zone maintenance • Private property leakage reduction in KwaDukuza • Regularisation of reticulation in Mandini • If funds approved, 30% demand reduction in Ndwedwe and Groutville . -

KWADUKUZA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY the KWAZULU-NATAL SCHEME SYSTEM Zoning Companion Document 1

KWADUKUZA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY THE KWAZULU-NATAL SCHEME SYSTEM Zoning Companion Document 1 NOVEMBER 2016 Prepared for: The Municipal Manager KwaDukuza Local Municipality 14 Chief Albert Luthuli Street KwaDukuza 4450 Tel: +27 032 437 5000 E-mail: [email protected] Contents 1.0 DEFINING LAND USE MANAGEMENT? ......................................................................................... 3 2.0 WHY DO WE NEED TO MANAGE LAND? ..................................................................................... 3 3.0 WHAT IS LAND USE PLANNING? ................................................................................................... 4 4.0 WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR LAND USE PLANNING? ................................................................ 4 5.0 THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................... 5 6.0 MANAGING LAND THROUGH A SUITE OF PLANS .................................................................... 6 7.0 WHAT ARE THE ELEMENTS OF THE LAND USE SCHEME? ................................................. 11 7.1 STATEMENTS OF INTENT (SOI) .............................................................................................. 11 7.2 LAND USE DEFINITIONS............................................................................................................. 12 7.3 ZONES 12 7.4 THE SELECTION OF ZONES AND THE PREPARATION OF A SCHEME MAP ................ 13 8.0 DEVELOPMENT PARAMETERS / SCHEME CONTROLS ....................................................... -

Ilembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 2Nd Quarter 2012

iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 2nd Quarter 2012 ILEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY NOVEMBER 2010 QUARTERLY ECONOMIC INDICATORSNOVEMBER 2010 AND INTELLIGENCE REPORT SECOND QUARTER 2012 APRIL-JUNE Enterprise iLembe Cnr Link Road and Ballito Drive Ballito, KwaZulu-Natal Tel: 032 – 946 1256 Fax: 032 – 946 3515 iLembe District Municipality – Quarterly Economic Indicators and Intelligence Report: 2nd Quarter 2012 FOREWORD This intelligence report comprises of an assessment of key economic indicators for the iLembe District Municipality for the second quarter of 2012, i.e. April to June 2012. This is the 6th edition of the quarterly reports, which are unique to iLembe as we are the only district municipality to publish such a report. The overall objective of this project is to present economic indicators and economic intelligence to assist Enterprise iLembe in driving its mandate, which is to drive economic development and promote trade and investment in the District of iLembe. This quarter sees the inclusion of updated annual data for 2011 which was released by Quantec in the first week of August 2012. The updated data shows that iLembe has grown by 2.9% in 2011, up from 2.7% in 2010, with the tertiary sector showing the most significant growth. Manufacturing has been taken over by ‘finance, insurance, real estate and business services’ as the highest contributor to GDP. The unemployment rate has reduced in 2011 to 21.3%, and iLembe has managed to attract 4% more highly skilled workers than the previous year. See further updated annual stats from page 41 onwards. All the regular quarterly statistics are also included from page 15. -

R603 (Adams) Settlement Plan & Draft Scheme

R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN & DRAFT SCHEME CONTRACT NO.: 1N-35140 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING ENVIRONMENT AND MANAGEMENT UNIT STRATEGIC SPATIAL PLANNING BRANCH 166 KE MASINGA ROAD DURBAN 4000 2019 FINAL REPORT R603 (ADAMS) SETTLEMENT PLAN AND DRAFT SCHEME TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.1.3. Age Profile ____________________________________________ 37 4.1.4. Education Level ________________________________________ 37 1. INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________ 7 4.1.5. Number of Households __________________________________ 37 4.1.6. Summary of Issues _____________________________________ 38 1.1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT ____________________________________ 7 4.2. INSTITUTIONAL AND LAND MANAGEMENT ANALYSIS ___________________ 38 1.2. PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ______________________________________ 7 4.2.1. Historical Background ___________________________________ 38 1.3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ________________________________________ 7 4.2.2. Land Ownership _______________________________________ 39 1.4. MILESTONES/DELIVERABLES ____________________________________ 8 4.2.3. Institutional Arrangement _______________________________ 40 1.5. PROFESSIONAL TEAM _________________________________________ 8 4.2.4. Traditional systems/practices _____________________________ 41 1.6. STUDY AREA _______________________________________________ 9 4.2.5. Summary of issues _____________________________________ 42 1.7. OUTLINE OF THE REPORT ______________________________________ 10 4.3. SPATIAL TRENDS ____________________________________________ 42 2. LEGISLATIVE -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

Rapid Urban Development and Fragmentation in a Post-Apartheid Era: the Case of Ballito, South Africa, 1994 to 2007

Rapid Urban Development and Fragmentation in a Post-Apartheid Era: The Case of Ballito, South Africa, 1994 to 2007 lames William Andrew Duminy A short dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for admittance to the degree ofMasters in Town and Regional Planning (MTRP) in the School of Architecture, Planning and Housing; University ofKwaZulu Natal (Durban). December 2007 Declaration I declare that this research is my own work and has not been used previously in fulfilment ofanother degree at the University ofKwaZulu Natal or elsewhere. Use ofthe work of others has been noted in the text. Signed: 0h=7 l.W.A. Duminy Dr R. Awuorh-Hayangah (Supervisor) Acknowledgements I must thank my supervisor, Dr Rosemary Awuohr-Hayangah, for her patient assistance. Special thanks to Nancy Odendaal for her encouragement and for kick-starting a nascent interest in critical social theory. Thanks to Helena Jacobs and Franyois van de Merwe (as well as the other interviewees) for their accommodation and invaluable assistance in the research process. Gratitude is also due to my parents and grandmother for providing some sort of continuity in a hectic year. I do not forget my late grandfather, without whom neither Ballito nor I would be the same. 11 Abstract Since 1994 a rapid rate of large-scale development in the region of Ballito, KwaZulu Natal, has generated significant urban spatial changes. This dissertation aimed to identify and examine the factors that have generated and sustained these changes. Qualitative information, sourced from interviews conducted with various professionals and actors involved in Ballito's recent development procedures, was utilized to this extent. -

ACTIVE HERITAGE Cc

Umdloti River Bridge FIRST PHASE HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED UMDLOTI RIVER BRIDGE AND REALIGNMENT OF MAIN ROAD P713, NDWEDWE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY ACTIVE HERITAGE cc. For: Kerry Seppings Environmental Consultants Frans Prins MA (Archaeology) P.O. Box 947 Howick 3290 [email protected] [email protected] December 2014 Fax: 086 7636380 Active Heritage cc for KSEMS i Umdloti River Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT........................................... 1 1.1. Details of the area surveyed: ........................................................................ 2 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION OF THE SURVEY ............................................. 5 2.1 Methodology ................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Restrictions encountered during the survey .................................................. 5 2.2.1 Visibility..................................................................................................... 5 2.2.2 Disturbance............................................................................................... 5 2.3 Details of equipment used in the survey........................................................ 5 3 DESCRIPTION OF SITES AND MATERIAL OBSERVED..................................... 5 3.1 Locational data ............................................................................................. 5 3.2 Description of heritage sites identified..........................................................