Homing Experiments with Arctic Terns Released Over Land and Sea by Jeremy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fastest Migration Highest

GO!” Everyone knows birds can fly. ET’S But not everyone knows that “L certain birds are really, really good at it. Meet a few of these champions of the skies. Flying Acby Ellen eLambeth; art sby Dave Clegg! Highest You don’t have to be a lightweight to fly high. Just look at a Ruppell’s griffon vulture (left). One was recorded flying at an altitude of 36,000 feet. That’s as high as passenger planes fly! In fact, it’s so high that you would pass out from lack of oxygen if you weren’t inside a plane. How does the vulture manage? It has Fastest (on the level) Swifts are birds that have that name for good special blood cells that make a small amount reason: They’re speedy! The swiftest bird using its own of oxygen go a long way. flapping-wing power is the common swift of Europe, Asia, and Africa (below). It’s been clocked at nearly 70 miles per hour. That’s the speed limit for cars on some highways. Vroom-vroom! Fastest (in a dive) Fastest Migration With gravity helping out, a bird can pick up extra speed. Imagine taking a trip of about 4,200 And no bird can go faster than a peregrine falcon in a dive miles. Sure, you could easily do it in an airplane. after prey (right). In fact, no other animal on Earth can go as But a great snipe (right) did it on the wing in just fast as a peregrine: more than 200 miles per hour! three and a half days! That means it averaged about 60 miles The prey, by the way, is usually another bird, per hour during its migration between northern which the peregrine strikes in mid-air with its balled-up Europe and central Africa. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Environmental Contaminants in Arctic Tern Eggs from Petit Manan Island

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine May 2001 Mission Statement U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “Our mission is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance the nation’s fish and wildlife and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” Suggested citation: Mierzykowski S.E., J.L. Megyesi and K.C. Carr. 2001. Environmental contaminants in Arctic tern eggs from Petit Manan Island. USFWS. Spec. Proj. Rep. FY96-MEFO-6-EC. Maine Field Office. Old Town, ME. 40 pp. Report reformatted 1/2009 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE MAINE FIELD OFFICE SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT: FY96-MEFO-6-EC ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS IN ARCTIC TERN EGGS FROM PETIT MANAN ISLAND Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Milbridge, Maine Prepared by: Steven E. Mierzykowski1, Jennifer L. Megyesi2, and Kenneth C. Carr3 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Maine Field Office 1033 South Main Street Old Town, Maine 04468 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge Main Street, P.O. Box 279 Milbridge, Maine 04658 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New England Field Office 70 Commercial Street, Suite 300 Concord, New Hampshire 03301-5087 May 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Petit Manan Island is a 3.5-hectare (~ 9 acre) island that lies approximately 4-kilometers (2.5-miles) from the coastline of Petit Manan Point, Steuben, Washington County, Maine. It is one of nearly 40 coastal islands within the Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Population Status of Arctic, Common, and Roseate Terns in the Gulf of Maine with Observations of Five Downeast Colonies

POPULATION STATUS OF ARCTIC, COMMON, AND ROSEATE TERNS IN THE GULF OF MAINE WITH OBSERVATIONS OF FIVE DOWNEAST COLONIES. prepared by: David C. ~olger and Matthew P. Drennan -1- Declines in numbers of Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea~ Common Terns S.hirundo, and Roseate Terns S.dougallii, throughout the northeast have been noted since 1940 (Drury 1973, Korshgen 1978, Nisbet 1973). Recent observations of Arctic and Common Terns in the Gulf of Maine have indicated a continuation and potential heightening of trends noted over the past forty years. Comparisons between counts of Arctic Terns by Drury in 1972-73 (Drury, 1973) and by Drury and Folger in 1983 (unpublished data), have indicated a population decline of as much as 40% over the last decade. Furthermore, the most recent complete survey of Common Terns in the state, done in 1977, indicated a parallel decline of 30%. Reductions in breeding habitat and in number of Roseate Terns has prompted ·fedet·"~"d considet-aticln ·fol~ "thl~eab~rH?~d" ~;;tatus (Nisbet, 1980). Because of a concern for terns in general and warnings indicated by previous surveys our work was initiated to further clarify the tern situation in the Gulf of Maine and to investigate the reasons for the decline in numbers. In the summer of 1984 we censused the outer islands of the Maine coast for terns from Metinic Island, at the western edge of Penobscot Bay, to Old Man Island, east of Cutler. We made detailed observations on five of the islands in order to examine the various factors that influence tern production. -

Arctic Map.Lay

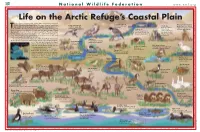

National Wildlife Federation www.nwf.org Longnose Sucker • Brown Bear • Moose • Barren Ground Caribou • Musk-ox • Polar Bear • Wolf • Arctic Fox • Wolverine • Land Otter • Arctic Ground Squirrel • Collared Lemming • Brown Lemming • Tundra Vole • Red-throated Loon • Tundra Swan • Black Brant • Canada Goose • Mallard • American Pintail • Green-winged Teal • American Wigeon • Greater Scaup • Oldsquaw • Common Eider • King Eider • Surf Scoter • Rough-legged Hawk • Golden Eagle • Gyrfalcon • Peregrine Falcon • Merlin • Willow Ptarmigan • Rock Ptarmigan • Semipalmated Plover • Lesser Golden Plover • Black-bellied Plover • Ruddy Turnstone • Snipe • Whimbrel • Pectoral Sandpiper • Least Sandpiper Life on the Arctic Refuge’s Coastal Plain hose in favor of opening the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling often call the region “barren,” and it can Peregrine falcon Arctic ground squirrel Long-tailed jaeger appear that way at first glance. But look again. The plain boasts the Nests on cliffs and Arctic fox Builds dens on low hills, T Feeds on eggs and river bluffs greatest wildlife diversity on Alaska’s northern coast, with denning polar Dens in coastal ridges and pingos where small birds bears, a year-round population of musk-oxen and many dozens of bird Lake trout hills, stream soils are well drained species—including vast numbers of migratory waterfowl. The refuge’s best Lives in larger lakes, banks and pingos known symbol is the 150,000-strong Porcupine caribou herd (named for a in foothills, that do not (mounds created freeze to the bottom by pressure under river), which migrates to the coastal plain every summer to feed, calve and permafrost) seek ocean breezes for relief from mosquitoes. -

The Longest Animal Migration in the World Revealed

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources Postbox 570, 3900 Nuuk, Greenland, WEB: www.natur.gl, E-mail: [email protected] The longest animal migration in the world revealed Astonishing new information on the wonders of animal migration has been revealed in a recent paper in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. An international research team found that the Arctic tern flies an incredible 70,000+ km on its annual migration trip from pole to pole - the equivalent of three trips to the moon and back over its lifetime. The researcher team, from Greenland, Denmark, the United States, Great Britain, and Iceland, have successfully mapped the impressive migratory movements of the Arctic tern. The results of the study verify what has been supposed for decades: that the Arctic tern does indeed conduct the longest annual migration in the world. Every year this small seabird travels an average of around 71,000 km roundtrip from Greenland to the Weddell Sea, on the shores of Antarctica, and back to the breeding grounds in Greenland. The research results not only confirm the Arctic tern as the champion of long-distance migration, but also held a few surprises in store for the research team. It turns out that the birds do not immediately travel south, but spent almost a month at-sea in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately 1,000 km north of the Azores. After this lengthy stop over, the birds continued their long journey south down the coast of northwest Africa, but around the Cape Verde Islands the birds behaviour surprised the researcher team again. -

Mike Benny : N Illustratio Earth’S Two Polar Regions Are the Coldest Places on the Planet

20 PRESERVE THE EARTH 17 Mike Benny : n Illustratio Earth’s two polar regions are the coldest places on the planet. The Arctic in the north and the Antarctic 2 in0 the south 17experience temperature extremes and seasons during which the sun does not rise. Yet plants and animals make homes in these places. the Antarctic the Arctic the Antarctic the Arctic Maps of the Earth’s two polar regions. Left to right: the Arctic and the Antarctic. In the Arctic, the snowy tundra and forest-filled taiga support myriad species: lumbering musk ox, warm-coated foxes and hares. On the Arctic sea ice, walruses and seals raise their young, and polar bears hunt among the floes. Indigenous round-trip to catch the 1 3 Antarctic summer before 2 communities have 5 returning to its Arctic 4 lived among the 6 breeding grounds. 7 ecosystems of the The seas teem with 8 10 Arctic for centuries. life in both regions. Sim- 9 14 Diverse species ilar species of plankton 13 11 of wildlife inhabit the and fish that feed ringed 12 Antarctic, the Earth’s seals in the Arctic and 15 16 coldest and driest conti- penguins in the nent. Emperor penguins Antarctic also support 17 18 21 huddle together on the productive commercial 19 20 ice, incubating eggs fisheries. in winters that bring These cold places Arctic species: Antarctic species: temperatures as low provide us with food 1 Snowy Owl 2 Southern Giant 3 Arctic Wolf Petrel as negative 48 degrees and natural resources. 4 Atlantic Puffin 12 Adélie Penguin Celsius. -

Mytern Booklet

MyTern AUSTRALIA A po ck et g ui de t o th e te rn s of A us tr al ia Caspian Terns, Glenn Ehmke MyTern.indd 1 22/5/19 10:44 am Co nt en ts Introduction ......................................................... 3 General habitat .....................................................4 Nesting habitat ..................................................... 5 Chicks ................................................................. 6 Feeding strategies ................................................. 7 Threats ............................................................... 8 Tips for identifying similar-looking terns.................... 9 !"#$%#&R(")*[,#&(--------------------------------------------------(./ 0#)1&(%1(\%345(-----------------------------------------------------(67 8*1%5*)%13(5#)1&---------------------------------------------------9/ Counting techniques ............................................ 32 BirdLife Australia projects .....................................38 Ke y fo r sp ec ie s’ p ro fil es bp = breeding plumage nbp = non-breeding plumage juv = juvenile plumage Note: the size (cm) of each species refers to body length, the images are not drawn to scale, and the distribution maps are based on all species’ records in Australia (from BirdLife Australia Atlas data). 2 MyTern.indd 2 22/5/19 10:44 am In tr od uc ti on 04%&(:**;,#5(%&(<([#,=($*>"<1%*1(?*)(>*1%5*)%13(@A&5)<,%<1( terns. MyTern contains key information about the habitat, =%&5)%:A5%*1B(1#&5%13()#CA%)#>#15&(<1=(%=#15%[$<5%*1(*?(5#)1&- Terns are in the subfamily Sterninae and are closely related to gulls, but are smaller, slimmer and longer-tailed. Noddies are very closely related and appear similar to terns (but have a wedge-shaped tail and inverse colouration: light cap and dark body). Twenty species of terns and three species of noddies have been recorded in Australia, including migratory &"#$%#&( <1=( D<3)<15&-( 8*&5( 5#)1&( 4A15( [&4( *)( <)54)*"*=&( (insects and crustaceans) by diving, skimming the surface of the water, or on the wing. -

Trans-Andean Passage of Migrating Arctic Terns Over Patagonia

Duffy et al.: Arctic Tern migration over Patagonia 155 TRANS-ANDEAN PASSAGE OF MIGRATING ARCTIC TERNS OVER PATAGONIA DAVID CAMERON DUFFY1, ALY MCKNIGHT2 & DAVID B. IRONS2 1Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawaii, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA ([email protected]) 21011 E. Tudor Rd. Migratory Bird Management, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, AK 99503, USA Received 19 April 2013; accepted 17 June 2013 SUMMARY DUFFY, D.C., MCKNIGHT, A. & IRONS, D.B. 2013. Trans-Andean passage of migrating Arctic Terns over Patagonia. Marine Ornithology 41: 155–159. We assessed migration routes of Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea breeding in Prince William Sound, Alaska, by deploying geolocator tags on 20 individuals in June 2007, recovering six upon their return in 2008 and 2009. The terns migrated south along the North and South American coastlines. As they neared the southern end of the Humboldt Current upwelling off Chile, they stopped their over-water migration and turned eastward, crossing the Andes to reach rich foraging areas in the South Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Argentina. Challenging sea and weather conditions, rather than paucity of food, likely deterred further movement south along the Chilean coast. Key words: Alaska, Arctic Tern, Andes, Argentina, Chile, geolocation, Humboldt Current, migration, Patagonia, Sterna paradisaea INTRODUCTION the tags’ view of the horizon and displaced positions calculated during the crossing, we defined the crossing distance as the distance Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea have the longest known migration between the last Pacific point and the first Atlantic point, ignoring of any bird species, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, covering up intermediate points occurring on land. -

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo and Arctic Tern S. Paradisaea Hybridization Produces Fertile Offspring

Tern hybrid produces backcross offspring Common Tern Sterna hirundo and Arctic Tern S. paradisaea hybridization produces fertile offspring Carolyn S. Mostello 1* , Derek LaFlamme 1,2 and Patricia Szczys 3 * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 1 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, 1 Rabbit Hill Road, Westborough, Massachusetts 01581, USA; 2 Central Connecticut State University, 1615 Stanley Street, New Britain, Connecticut 06053, USA; 3 Eastern Connecticut State University, 83 Windham Street, Willimantic, Connecticut 06226, USA. Abstract This study provides the first molecular evidence for hybridization between Arctic Terns Sterna paradisaea and Common Terns S. hirundo . We studied a mixed pair (P1; male Arctic Tern and female Common Tern) and its offspring on Penikese Island, Massachusetts, USA in 2007–2015. The pair maintained a long-term pair bond (8 years); its reproductive performance was comparable to that of Common Terns and higher than that of Arctic Terns at the site. Molecular analyses confirmed that all young raised by the pair (at least 5 males and 4 females) were biological offspring. We describe hybrid young and the adult hybrid in detail to facilitate field identification. Although F1 hybrid young were intermediate between the parent species in certain characteristics, dark feathers extending below the eye, in particular, gave them a distinctly Arctic Tern-like appearance; however, all had secondary feathers that were darker than the wing-coverts, like Common Terns. We detected one male F1 hybrid that returned to breed; it retained some features intermediate between the parent species, but we qualitatively judged it to be more Common Tern-like. It mated with a Common Tern and produced three confirmed backcross hybrid young that closely resembled Common Terns. -

Arctic Activities

Arctic Background AArrccttiicc AAccttiivviittiieess TThhee TToolleeddoo ZZoooo Arctic Background The Arctic Geography There are several ways that people define the region of the world known as the Arctic. Commonly, the Arctic is often described as a region of snow and ice surrounding the North Pole. This may appear to be true, especially during the winter. Yet, a large part of the Arctic is composed of forested tundra where a large number of plants and animals live. Technically, scientists define the Arctic as the region above 66 degrees, 30 minutes of North Latitude, an area known as the Arctic Circle. Within this region, the sun does not set in the summer. Other definitions rely on the extent of tundra vegetation, distribution of animals, the presence or absence of permafrost, temperature or the southern extent of pack ice. Some simply define the Arctic as a very dry, cold desert. Whatever the definition, the Arctic is large, almost equal in size to the entire continent of North America. Ironically, though most of the Arctic is made up of water it is technically a desert. Since the water is frozen most of the year, it is not accessible to plants or animals. Because of the extreme cold, the atmosphere is unable to hold enough moisture for it to snow or rain very much. In the summer, when the ice melts, water does become available in the lower Arctic regions. Since there is no drainage, it collects and pools to form huge wetlands. The layer of permafrost beneath the surface stays permanently frozen and does not allow water to percolate through the soil.