Changing Compensation in MLB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAA Division I Baseball Records

Division I Baseball Records Individual Records .................................................................. 2 Individual Leaders .................................................................. 4 Annual Individual Champions .......................................... 14 Team Records ........................................................................... 22 Team Leaders ............................................................................ 24 Annual Team Champions .................................................... 32 All-Time Winningest Teams ................................................ 38 Collegiate Baseball Division I Final Polls ....................... 42 Baseball America Division I Final Polls ........................... 45 USA Today Baseball Weekly/ESPN/ American Baseball Coaches Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 46 National Collegiate Baseball Writers Association Division I Final Polls ............................................................ 48 Statistical Trends ...................................................................... 49 No-Hitters and Perfect Games by Year .......................... 50 2 NCAA BASEBALL DIVISION I RECORDS THROUGH 2011 Official NCAA Division I baseball records began Season Career with the 1957 season and are based on informa- 39—Jason Krizan, Dallas Baptist, 2011 (62 games) 346—Jeff Ledbetter, Florida St., 1979-82 (262 games) tion submitted to the NCAA statistics service by Career RUNS BATTED IN PER GAME institutions -

Sabermetrics: the Past, the Present, and the Future

Sabermetrics: The Past, the Present, and the Future Jim Albert February 12, 2010 Abstract This article provides an overview of sabermetrics, the science of learn- ing about baseball through objective evidence. Statistics and baseball have always had a strong kinship, as many famous players are known by their famous statistical accomplishments such as Joe Dimaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ted Williams’ .406 batting average in the 1941 baseball season. We give an overview of how one measures performance in batting, pitching, and fielding. In baseball, the traditional measures are batting av- erage, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage, but modern measures such as OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) are better in predicting the number of runs a team will score in a game. Pitching is a harder aspect of performance to measure, since traditional measures such as winning percentage and earned run average are confounded by the abilities of the pitcher teammates. Modern measures of pitching such as DIPS (defense independent pitching statistics) are helpful in isolating the contributions of a pitcher that do not involve his teammates. It is also challenging to measure the quality of a player’s fielding ability, since the standard measure of fielding, the fielding percentage, is not helpful in understanding the range of a player in moving towards a batted ball. New measures of fielding have been developed that are useful in measuring a player’s fielding range. Major League Baseball is measuring the game in new ways, and sabermetrics is using this new data to find better mea- sures of player performance. -

Understanding Advanced Baseball Stats: Hitting

Understanding Advanced Baseball Stats: Hitting “Baseball is like church. Many attend few understand.” ~ Leo Durocher Durocher, a 17-year major league vet and Hall of Fame manager, sums up the game of baseball quite brilliantly in the above quote, and it’s pretty ridiculous how much fans really don’t understand about the game of baseball that they watch so much. This holds especially true when you start talking about baseball stats. Sure, most people can tell you what a home run is and that batting average is important, but once you get past the basic stats, the rest is really uncharted territory for most fans. But fear not! This is your crash course in advanced baseball stats, explained in plain English, so that even the most rudimentary of fans can become knowledgeable in the mysterious world of baseball analytics, or sabermetrics as it is called in the industry. Because there are so many different stats that can be covered, I’m just going to touch on the hitting stats in this article and we can save the pitching ones for another piece. So without further ado – baseball stats! The Slash Line The baseball “slash line” typically looks like three different numbers rounded to the thousandth decimal place that are separated by forward slashes (hence the name). We’ll use Mike Trout‘s 2014 slash line as an example; this is what a typical slash line looks like: .287/.377/.561 The first of those numbers represents batting average. While most fans know about this stat, I’ll touch on it briefly just to make sure that I have all of my bases covered (baseball pun intended). -

Name of the Game: Do Statistics Confirm the Labels of Professional Baseball Eras?

NAME OF THE GAME: DO STATISTICS CONFIRM THE LABELS OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL ERAS? by Mitchell T. Woltring A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Leisure and Sport Management Middle Tennessee State University May 2013 Thesis Committee: Dr. Colby Jubenville Dr. Steven Estes ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not be where I am if not for support I have received from many important people. First and foremost, I would like thank my wife, Sarah Woltring, for believing in me and supporting me in an incalculable manner. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Julie Woltring, for always supporting and encouraging me to make myself a better person. I would be remiss to not personally thank Dr. Colby Jubenville and the entire Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Without Dr. Jubenville convincing me that MTSU was the place where I needed to come in order to thrive, I would not be in the position I am now. Furthermore, thank you to Dr. Elroy Sullivan for helping me run and understand the statistical analyses. Without your help I would not have been able to undertake the study at hand. Last, but certainly not least, thank you to all my family and friends, which are far too many to name. You have all helped shape me into the person I am and have played an integral role in my life. ii ABSTRACT A game defined and measured by hitting and pitching performances, baseball exists as the most statistical of all sports (Albert, 2003, p. -

Salary Correlations with Batting Performance

Salary correlations with batting performance By: Jaime Craig, Avery Heilbron, Kasey Kirschner, Luke Rector, Will Kunin Introduction Many teams pay very high prices to acquire the players needed to make that team the best it can be. While it often seems that high budget teams like the New York Yankees are often very successful, is the high price tag worth the improvement in performance? We compared many statistics including batting average, on base percentage, slugging, on base plus slugging, home runs, strike outs, stolen bases, runs created, and BABIP (batting average for balls in play) to salaries. We predicted that higher salaries will correlate to better batting performances. We also divided players into three groups by salary range, with the low salary range going up to $1 million per year, the mid-range salaries from $1 million to $10 million per year, and the high salaries greater than $10 million per year. We expected a stronger correlation between batting performance and salaries for players in the higher salary range than the correlation in the lower salary ranges. Low Salary Below $1 million In figure 1 is a correlation plot between salary and batting statistics. This correlation plot is for players that are making below $1 million. We see in all of the plots that there is not a significant correlation between salary and batting statistics. It is , however, evident that players earning the lowest salaries show the lowest correlations. The overall trend for low salary players--which would be expected--is a negative correlation between salary and batting performance. This negative correlation is likely a result of players getting paid according to their specific performance, or the data are reflecting underpaid rookies who have not bloomed in the major leagues yet. -

Utilizing the Impact Test to Predict Performance in College Baseball Hitters by Ryan Nussbaum a Thesis Submitted to the Honors C

Utilizing the ImPACT Test to Predict Performance in College Baseball Hitters By Ryan Nussbaum A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Psychology (B.S.) THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY2013 .- 1 The University of Arizona Electronic Theses and Dissertations Reproduction and Distribution Rights Form The UA Campus Repository supports the dissemination and preservation of scholarship produced by University of Arizona faculty, researchers, and students. The University library, in collaboration with the Honors College, has established a collection in the UA Campus Repository to share, archive, and preserve undergraduate Honors theses. Theses that are submitted to the UA Campus Repository are available for public view. Submission of your thesis to the Repository provides an opportunity for you to showcase your work to graduate schools and future employers. It also allows for your work to be accessed by others in your discipline, enabling you to contribute to the knowledge base in your field. Your signature on this consent form will determine whether your thesis is included in the repository. Name (Last, First, Middle) N usSbo."'M.' ll. 'lo.-/1, ?t- \A l Degree tiUe (eg BA, BS, BSE, BSB, BFA): B. 5. Honors area (eg Molecular and Cellular Biology, English, Studio Art): e.si'c ko to~ 1 Date thesis submitted to Honors College: M ,..., l, Z-.0[3 TiUe of Honors thesis: LH;tn.. ;J +he-- L-\?1kT 1~:.+ 1o P~-t P~.t>('.,.,. ....... ~ ~ ~~ '""' G.~~ l3~~~u (-(t~..s The University of Arizona Library Release Agreement I hereby grant to the University of Arizona Library the nonexclusive worldwide right to reproduce and distribute my dissertation or thesis and abstract (herein, the "licensed materials"), in whole or in part, in any and all media of distribution and in any format in existence now or developed in the Mure. -

Combining Radar and Optical Sensor Data to Measure Player Value in Baseball

sensors Article Combining Radar and Optical Sensor Data to Measure Player Value in Baseball Glenn Healey Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of California, Irvine, CA 92617, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Evaluating a player’s talent level based on batted balls is one of the most important and difficult tasks facing baseball analysts. An array of sensors has been installed in Major League Baseball stadiums that capture seven terabytes of data during each game. These data increase interest among spectators, but also can be used to quantify the performances of players on the field. The weighted on base average cube model has been used to generate reliable estimates of batter performance using measured batted-ball parameters, but research has shown that running speed is also a determinant of batted-ball performance. In this work, we used machine learning methods to combine a three-dimensional batted-ball vector measured by Doppler radar with running speed measurements generated by stereoscopic optical sensors. We show that this process leads to an improved model for the batted-ball performances of players. Keywords: Bayesian; baseball analytics; machine learning; radar; intrinsic values; forecasting; sensors; batted ball; statistics; wOBA cube 1. Introduction The expanded presence of sensor systems at sporting events has enhanced the enjoy- ment of fans and supported a number of new applications [1–4]. Measuring skill on batted balls is of fundamental importance in quantifying player value in baseball. Traditional measures for batted-ball skill have been based on outcomes, but these measures have a low Citation: Healey, G. Combining repeatability due to the dependence of outcomes on variables such as the defense, the ball- Radar and Optical Sensor Data to park dimensions, and the atmospheric conditions [5,6]. -

Sensorimotor Abilities Predict On-Field Performance in Professional Baseball

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Sensorimotor abilities predict on- feld performance in professional baseball Received: 18 August 2017 Kyle Burris1, Kelly Vittetoe2, Benjamin Ramger2, Sunith Suresh1, Surya T. Tokdar1, Accepted: 14 December 2017 Jerome P. Reiter1 & L. Gregory Appelbaum2,3 Published: xx xx xxxx Baseball players must be able to see and react in an instant, yet it is hotly debated whether superior performance is associated with superior sensorimotor abilities. In this study, we compare sensorimotor abilities, measured through 8 psychomotor tasks comprising the Nike Sensory Station assessment battery, and game statistics in a sample of 252 professional baseball players to evaluate the links between sensorimotor skills and on-feld performance. For this purpose, we develop a series of Bayesian hierarchical latent variable models enabling us to compare statistics across professional baseball leagues. Within this framework, we fnd that sensorimotor abilities are signifcant predictors of on- base percentage, walk rate and strikeout rate, accounting for age, position, and league. We fnd no such relationship for either slugging percentage or felder-independent pitching. The pattern of results suggests performance contributions from both visual-sensory and visual-motor abilities and indicates that sensorimotor screenings may be useful for player scouting. Ted Williams, one of the most legendary baseball players of all time, once said, “I think without question the hard- est single thing to do in sport is to hit a baseball”. Advances in sport science continue to validate Williams’ claim; hitting a pitched baseball places incredible demands on athletes’ visual systems. We now know that Major League Baseball (MLB) pitches move at speeds near the processing limits of the vestibular-ocular tracking1, leaving the batter with mere milliseconds to decipher the pitch, project its trajectory, decide to swing, and coordinate the timing and trajectory of a 2.25-inch diameter bat. -

Does the Defensive Shift Employed by an Opposing Team Affect an MLB

Does the Defensive Shift Employed by an Opposing team affect an MLB team’s Batted Ball Quality and Offensive Performance? 11/20/2019 Abstract This project studies proportions of batted ball quality across the 2019 MLB season when facing two different types of defensive alignment. It also attempts to answer if run production is affected by shifts. Batted ball quality is split into six groups (barrel, solid contact, flare, poor (topped), poor (under), and poor(weak)) while defensive alignments are split into two (no shift and shift). Relative statistics come from all balls put in play excluding sacrifice bunts in the 2019 MLB season. The study shows there to be differences in the proportions of batted ball quality relative to defensive alignment. Specifically, the proportion of barrels (balls barreled) against the shift was greater than the proportion of barrels against no shift. Barrels also proved to result in the highest babip (batting average on balls in play) + slg (slugging percentage), where babip + slg then proved to be a good predictor of overall offensive performance measured in woba (weighted on-base average). There appeared to be a strong positive correlation between babip + slg and woba. MLB teams may consider this data when deciding which defensive alignment to play over the course of a game. However, they will most likely want to extend this research by evaluating each player on a case by case basis. 1 Background and Signifigance Do MLB teams hit the ball better when facing a certain type of defensive alignment? As the shift becomes increasingly employed in Major League Baseball these types of questions become more and more important. -

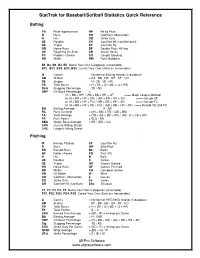

Stattrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference

StatTrak for Baseball/Softball Statistics Quick Reference Batting PA Plate Appearances HP Hit by Pitch R Runs CO Catcher's Obstruction H Hits SO Strike Outs 2B Doubles SH Sacrifice Hit (sacrifice bunt) 3B Triples SF Sacrifice Fly HR Home Runs DP Double Plays Hit Into OE Reaching On-Error SB Stolen Bases FC Fielder’s Choice CS Caught Stealing BB Walks RBI Runs Batted In B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 Name Your Own Categories (renamable) BS1, BS2, BS3, BS4, BS5 Create Your Own Statistics (renamable) G Games = Number of Batting records in database AB At Bats = PA - BB - HP - SH - SF - CO 1B Singles = H - 2B - 3B - HR TB Total Bases = H + 2B + (2 x 3B) + (3 x HR) SLG Slugging Percentage = TB / AB OBP On-Base Percentage = (H + BB + HP) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Major League Method or (H + BB + HP + OE) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE or (H + BB + HP + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include FC or (H + BB + HP + OE + FC) / (AB + BB + HP + SF) <=== Include OE and FC BA Batting Average = H / AB RC Runs Created = ((H + BB) x TB) / (AB + BB) TA Total Average = (TB + SB + BB + HP) / (AB - H + CS + DP) PP Pure Power = SLG - BA SBA Stolen Base Average = SB / (SB + CS) CHS Current Hitting Streak LHS Longest Hitting Streak Pitching IP Innings Pitched SF Sacrifice Fly R Runs WP Wild Pitch ER Earned-Runs Bk Balks BF Batters Faced PO Pick Offs H Hits B Balls 2B Doubles S Strikes 3B Triples GS Games Started HR Home Runs GF Games Finished BB Walks CG Complete Games HB Hit Batter W Wins CO Catcher's Obstruction L Losses SO Strike Outs Sv Saves SH Sacrifice Hit -

RELATIVITY and NORMALIZATION What Is It?

RELATIVITY AND NORMALIZATION What is it? • Relativity and Normalization can be used when making comparisons between and among players, teams and eras. • Helps “level the playing field” when comparing stats • Can help determine whether it was “more difficult” for Babe Ruth to hit home runs in the 1920s, or Sammy Sosa to hit home runs in the 1990s. • Transforms raw statistics into a new number, up to four decimal places. Example • Ralph Kiner, of the Pirates, in 1947: • Kiner hit 51 HR in 565 at-bats, for an HR to at-bat ratio of 51/565 = .0903 • Shows that he hit about 9 HR for every 100 at-bats, normally • In the Major Leagues in 1947: All players on the 16 teams hit a total of 1,565 home runs in 84,436 at-bats. What is the ratio? • 1565/84436 = .0185, or showing the “average” player hit slightly less than 2 HR per 100 at-bats • To find the normalization number, divide Kiner’s number by the overall number • .0903/.0185 = 4.8689 Interpretation • How do we interpret the normalization number? • One possibility is that Kiner was nearly 5 times better than the the average home run hitter of 1947. • By figuring these out for certain statistics, you can compare players from different eras — or even narrowing down between the AL and the NL. Demonstrating Sabermetrics • In 1928, Hall of Famer Heinie Manush had a slugging percentage of .575. If the slugging percentage of the AL was .397, find his normalized ratio and give an interpretation to this number. -

1. Intro to Scorekeeping

1. Intro To Scorekeeping The following terms will be used on this site: Cell: The term cell refers to the square in which the player’s at-bat is recorded. In this illustration, the cell is the box where the diagram is drawn. Scorecard, Scorebook: Will be used interchangeably and refer to the sheet that records the player and scoring information during a baseball game. Scorekeeper: Refers to someone on a team that keeps the score for the purposes of the team. Official Scorer: The designated person whose scorekeeping is considered the official record of the game. The Official Scorer is not a member of either team. Baseball’s Defensive Positions To “keep score” of a baseball game it is essential to know the defensive positions and their shorthand representation. For example, the number “1” is used to refer to the pitcher (P). NOTE : In the younger levels of youth baseball leagues 10 defensive players are used. This 10 th position is know as the Short Center Fielder (SC) and is positioned between second base and the second baseman, on the beginning of the outfield grass. The Short Center Fielder bats and can be placed anywhere in the batting lineup. Defensive Positions, Numbers & Abbreviations Position Number Defensive Position Position Abbrev. 1 Pitcher P 2 Catcher C 3 First Baseman 1B 4 Second Baseman 2B 5 Third Baseman 3B 6 Short Stop SS 7 Left Fielder LF 8 Center Fielder CF 9 Right Fielder RF 10 Short Center Fielder SC The illustration below shows the defensive position for the defense. Notice the short center fielder is illustrated for those that are scoring youth league games.