126586379.23.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Scottish Record Society. [Publications]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5606/scottish-record-society-publications-815606.webp)

Scottish Record Society. [Publications]

00 HANDBOUND AT THE L'.VU'ERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY, ^5^ THE Commissariot IRecorb of EMnbutGb. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. PART III. VOLUMES 81 TO iji—iyoi-iSoo. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLEKK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1899. EDINBURGH '. PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. PREFATORY NOTE. This volume completes the Index to this Commissariot, so far as it is proposed by the Society to print the same. It includes all Testaments recorded before 31st December 1800. The remainder of the Record down to 31st December 1829 is in the General Register House, but from that date to the present day it will be found at the Commissary Office. The Register for the Eighteenth Century shows a considerable falling away in the number of Testaments recorded, due to some extent to the Local Registers being more taken advantage of On the other hand, a number of Testaments of Scotsmen dying in England, the Colonies, and abroad are to be found. The Register for the years following on the Union of the Parliaments is one of melancholy interest, containing as it does, to a certain extent, the death-roll of the ill-fated Darien Expedition. The ships of the Scottish Indian and African Company mentioned in " " " " the Record are the Caledonia," Rising Sun," Unicorn," Speedy " " " Return," Olive Branch," Duke of Hamilton (Walter Duncan, Skipper), " " " " Dolphin," St. Andrew," Hope," and Endeavour." ®Ij^ C0mmtssari0t ^ttoxi oi ®5tnburglj. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS. THIRD SECTION—1701-180O. ••' Abdy, Sir Anthony Thomas, of Albyns, in Essex, Bart. -

The Duality of Human Nature Science and the Unexplained The

Chapter Plot Character Vocabulary Context 1 The Story of Passing a strange-looking door whilst out for a walk, Enfield tells Dr Henry Jekyll A doctor and experimental scientist who aberration Fin-de-siècle fears – at the end of the 19th the Door Utterson about incident involving a man (Hyde) trampling on a is both wealthy and respectable. century, there were growing fears about: young girl. The man paid the girl compensation. Enfield says the abhorrent migration and the threats of disease; man had a key to the door (which leads to Dr Jekyll’s laboratory) Mr Edward Hyde A small, violent and unpleasant-looking sexuality and promiscuity; moral degeneration and decadence. 2 Search for Utterson looks at Dr Jekyll’s will and discovers that he has left his man; an unrepentant criminal. allegory Hyde possessions to Mr Hyde in the event of his disappearance. Utterson watches the door and sees Hyde unlock it, then goes to warn Jekyll. allusion Gabriel Utterson A calm and rational lawyer and friend of Victorian values – from the 1850s to the Jekyll isn’t in, but Poole tells him that the servants have been told Jekyll. to obey Hyde. anxiety turn of the century, British society outwardly displayed values of sexual A conventional and respectable doctor 3 Dr Jekyll was Two weeks later, Utterson goes to a dinner party at Jekyll’s house Dr Hastie Lanyon atavism restraint, low tolerance of crime, religious Quite at Ease and tells him about his concerns. Jekyll laughs off his worries. and former friend of Jekyll. morality and a strict social code of conduct. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

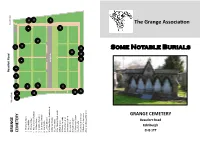

Some Notable Burials

Beaufort Road East Gate GRANGE West Gate 5 7 CEMETERY 1 2 3 4 6 8 1 Thomas Nelson 24 2 Hugh Miller 9 10 3 Thomas Oliver 4 Rev Thomas Chalmers 23 11 5 William Stuart 6 Charles MacLaren 22 12 7 Sir James Gowans 8 Ivan Szabo 9 James Moonie 28 10 William Stuart Cruickshank 13 11 Michael Taylor 12 James Smith 13 Sir Thomas Dick Lauder 14 Robin Cook 14 15 David Kennedy 21 16 Thomas Usher 17 Thomas Guthrie 18 James Thin 19 Andrew Usher 18 20 Alexander Cowan 20 21 John Usher 22 John Bartholomew 19 17 16 15 23 Robert Middlemass 24 Canon Edward Hannan Some Notable Burials Some Notable GRANGE CEMETERY The Grange Association Grange The Beaufort Road Beaufort Edinburgh EH9 1TT 24. Canon Edward Joseph Hannan (1836-1891) Canon Edward Joseph Hannan is known for his Grange Cemetery was established in 1847 by the Southern Cemetery Company Ltd. on involvement in the founding of Hibernian land donated by the Dick Lauder family of the Grange Estate. Designed by David Bryce, Football Club, ‘Hibs’. In the early 19th century the architect, the site occupied an open space of more than 12 acres and was built on a many Irish people migrated to Edinburgh, rectangular pattern around central vaulted catacombs which are built into the crest of living around the Cowgate, Grassmarket, West the hill. Bryce also designed the lodge, modified by J.G.Adams in 1890, and a mortuary Bow, Pleasance, Holyrood, St John's, West chapel which was never built. The cemetery lies on Beaufort Road and has been Port, Candlemaker's Row, Potterrow, expanded to Kilgraston Road. -

List of Illustrations

L ist of I llu str a tio ns VOLUM E II P AG E W S IR ALTER S COTT Fr onti: piece AB B EY STRAND ’ HOLYROOD AND ARTH UR s S EAT TH N V O O CH E A E , H LYR OD APEL W T D O CH ES ERN OORWAY, H LYROOD APEL ’ J EANIE DEANS COTT AGE ’ SYM SON TH P T O S C T E RIN ER S H U E , OWGA E TH F O W IN TH V E L DDEN ALL , E ENNEL TH E POTT ERROW ’ O L D GR EYP RLARS CH URCH ’ MARTYRS MONUMENT ’ H ERTOT S HOSPITAL EDTNE URGH IN T 560 L As S WAD E COTT AGE ' TH E CANONGAT E D URING T H E PROCESSION OF G IV A T 1 822 EORGE , UGUS WILLIAM DRUMMOND OF HAWTHORNDEN ALLAN RAMSAY TH UNl V E RS IT Y SO TH B E , U RIDGE H T AxT TH B OM P . J O N , E RO EDDLER A BELLE AND BEAU List of Illustra tions P AG R S S CouNT E s s O E T U ANNA , F GLIN ON L O KA HENRY HOM E , RD MES L ORD NEWTON ’ JOH NNIE D OWI E S TA V ERN JOH NNIE DOWIE WILLIAM CO K E AND J OH N GUTHRIE A MORRI S DAN CER L E E L EWE s M RS . M R . AND C CH M RS . Y T M R . LIN AND A ES O L D PLAYHOUSE CLOSE ST G TH NORTHW T . -

Corporate Responses to Lock Picking in the Scottish Town, 1488 –1788

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 137 (2007), 471–486 ALLEN: A PERNICIOUS AND WICKED CUSTOM | 471 A pernicious and wicked custom: corporate responses to lock picking in the Scottish town, 1488 –1788 Aaron M Allen* ABSTRACT While the use of lock picking for criminal purposes was not confined to towns, there were several specifically urban, unique responses to it from the craft guilds of Scotland’s burghs. In an urban context, the prevention of lock picking can be seen to have depended largely on a framework of corporatism. This article examines how security was provided, the role of locks in the urban environment, the deficiencies of lock technology, and the exploits of the infamous Deacon Brodie. While it was impossible to make a pick-proof, warded lock, the incorporations did what they could to contain this ‘pernicious and wicked custom’. INTRODUCTION measures dealing with the problem. Aside from the technical side of security, as shall be seen, In early modern Scotland the physical act of there were several other corporate responses to assaulting someone in their home was known what was a serious crime in early modern urban as ‘hamesucken’ (Robinson 1992, 264). One society. element of this crime was the physical act of To explore picking as an urban problem we entering unlawfully. Technology was, and still will need to understand how locks functioned is, the most common deterrent to unlawful entry. and, in particular, how they were used in burghs. Though lock picking was not exclusively an To understand the criminal side of what was urban problem, there is evidence of specifically a normal day-to-day technique for legitimate urban responses to it, as the craftsmen who made locksmiths, it will be helpful to look at the the lock mechanisms were charged with finding infamous case of Deacon Brodie. -

Jean Brodie and Edinburgh: Personality and Place in Muriel Spark's the Rp Ime of Miss Jean Brodie Philip E

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 13 | Issue 1 Article 5 1978 Jean Brodie and Edinburgh: Personality and Place in Muriel Spark's The rP ime of Miss Jean Brodie Philip E. Ray Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ray, Philip E. (1978) "Jean Brodie and Edinburgh: Personality and Place in Muriel Spark's The rP ime of Miss Jean Brodie," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol13/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Philip E. Ray Jean Brodie and Edinburgh: Personality and Place in Murial Spark's The Prime ofMiss Jean Brodie The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is a novel of Edinburgh. This phrase applies, however, in both the ordinary sense--the novel is set in Edinburgh and presents the reader with characters who were born and have spent their lives there--and the strict sense--the novel is, at its deepest level, "about Edinburgh."l Jean Brodie herself functions as a personification of certain attitudes common to the citizens of Edinburgh, attitudes that are basically religious or theological in nature. In the most concrete terms, her hostility to the Roman Cat~ olic Church is one such attitude: although she was "by tem perament suited only" to this faith, she "shunned" it because she was capable of "bringing to her support a rigid Edinburgh born side of herself when the Catholic Church was in ques tion.,,2 In a larger and more comprehensive view, however, Jean Brodie is the literal embodiment of the city's Calvinist spirit. -

Going Underground Discover the Hidden Treasures of One of the World’S Most Exciting Cities

EDINBURGHAIRPORT.COM ISSUE 07 WINTER 2014 CAPITALEDINBURGH AIRPORT FASHION LIFESTYLE SHOPPING TRAVEL GOING UNDERGROUND DISCOVER THE HIDDEN TREASURES OF ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST EXCITING CITIES ~ WINTER 2014 ~ CAPITAL EDINBURGH AIRPORT’S PASSENGER MAGAZINE 6 VISIT SCOTLAND Explore this fascinating CELEBRATE country with Virgin Atlantic 44 IN SCOTLAND 34 PROPERTY Looking forward to the BOOMING Year of Food & Drink MARKET 13 NEW YEAR House sales are at a record HELLO 2015! high in Scotland’s capital Join in the fun of Edinburgh’s world-famous 40 ATTRACTIONS Hogmanay festival LIGHTS AND ACTION! 14 ATTRACTIONS Discover for yourself the LET’S TAKE real-life Scottish locations A WALK from the big screen The Royal Mile is packed with history, attractions 43 COMPETITION and lots to explore THE SKYE’S THE LIMIT 18 SHOPPING Win a fabulous stay at THE Duisdale House on Skye PERSONAL TOUCH 44 ATTRACTIONS Find the perfect jewellery STARS IN at Hamilton & Inches YOUR EYES Look up to see the best light 20 ENTERTAINMENT show in the universe! MOVIES AND SHAKERS 47 SHOPPING Enjoy a fabulous WINTER festive evening of good WARMER 6 14 food and films at The Scotch Whisky Harvey Nichols Experience is the perfect place to enjoy a dram 23 AIRPORT NEWS SAFETY AT 50 SCOTCH OUR HEART WHISKIES OF Edinburgh Airport DISTINCTION unveils its new £25m Raise a glass to William passenger security facility Grant & Sons latest releases 26 MEET OUR STAFF 53 DESTINATION WE’RE HERE LONDON’S TO HELP HIDDEN GEMS Security officer Susan Clark Go off the beaten track to talks about her role uncover the capital’s 31 amazing attractions 28 SHOPPING REGULARS 20 CHRISTMAS 48 Airport news WISH LIST 52 Destination map Find some festive crackers 58 Tail plane column at Multrees Walk 31 TRAVEL AMAZING 23 AMERICA Capital is written, designed and published by Connect Publications (Scotland) Ltd on behalf of Edinburgh Airport. -

Edinburgh on the Rocks - a Guide with a Twist

Edinburgh on the Rocks - A Guide with a Twist - A city map 4 Key of venue: see back 5 6 How to Treat me Right (An Instruction Manual to the Guide) -Hot- - Read me carefully - don‘t just tell everyone you did. - Appreciate and honour me. - Recommend me (even if you‘d rather not). - Trust and obey me. - Believe in me - and only me. - Cuddle me from time to time, a book needs love too. - Let me be the last thing you think of before you go to bed, and the first thing once you get up. - Pass me on to people you hold very dear, but don‘t just give me away to anybody. -Not- - Don‘t hit other people or animals with me. - Don‘t throw me away in a fit of an ger or exhaustion. - Don‘t drown me by spilling any kind of liquid over me. - Don‘t rip me into pieces. - Don‘t tease me - a travel guide has feelngs too. - Don‘t eat me - no matter how hungry you get from sightseeing. - Don‘t burn me on a bonfire. - Never ever forget me! 7 Contents Intro 9 History 10 Lifestyle & Culture 39 Sights & Activities 59 Day Trips 103 Nightlife & Entertainment 119 Food & Drink 133 Accommodation &Transport 149 Dos & Don'ts 152 The team 154 8 Edinburgh Spotting Choose your destination. Choose your flight. Choose an effing big suitcase. Choose a bed to rest your weary head on, and be just as tired in the morning. Choose square sausages, bacon rashers, potato scones, baked beans and how you like your eggs. -

Biographical Index of Former RSE Fellows 1783-2002

FORMER RSE FELLOWS 1783- 2002 SIR CHARLES ADAM OF BARNS 06/10/1780- JOHN JACOB. ABEL 19/05/1857- 26/05/1938 16/09/1853 Place of Birth: Cleveland, Ohio, USA. Date of Election: 05/04/1824. Date of Election: 03/07/1933. Profession: Royal Navy. Profession: Pharmacologist, Endocrinologist. Notes: Date of election: 1820 also reported in RSE Fellow Type: HF lists JOHN ABERCROMBIE 12/10/1780- 14/11/1844 Fellow Type: OF Place of Birth: Aberdeen. ROBERT ADAM 03/07/1728- 03/03/1792 Date of Election: 07/02/1831. Place of Birth: Kirkcaldy, Fife.. Profession: Physician, Author. Date of Election: 28/01/1788. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Architect. ALEXANDER ABERCROMBY, LORD ABERCROMBY Fellow Type: OF 15/10/1745- 17/11/1795 WILLIAM ADAM OF BLAIR ADAM 02/08/1751- Place of Birth: Clackmannanshire. 17/02/1839 Date of Election: 17/11/1783. Place of Birth: Kinross-shire. Profession: Advocate. Date of Election: 22/01/1816. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Advocate, Barrister, Politician. JAMES ABERCROMBY, BARON DUNFERMLINE Fellow Type: OF 07/11/1776- 17/04/1858 JOHN GEORGE ADAMI 12/01/1862- 29/08/1926 Date of Election: 07/02/1831. Place of Birth: Ashton-on-Mersey, Lancashire. Profession: Physician,Statesman. Date of Election: 17/01/1898. Fellow Type: OF Profession: Pathologist. JOHN ABERCROMBY, BARON ABERCROMBY Fellow Type: OF 15/01/1841- 07/10/1924 ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL ADAMS Date of Election: 07/02/1898. Date of Election: 19/12/1910. Profession: Philologist, Antiquary, Folklorist. Profession: Consulting Engineer. Fellow Type: OF Notes: Died 1918-19 RALPH ABERCROMBY, BARON DUNFERMLINE Fellow Type: OF 06/04/1803- 02/07/1868 JOHN COUCH ADAMS 05/06/1819- 21/01/1892 Date of Election: 19/01/1863. -

Trails Edinburgh in the Time of the Victorians: the Jekyll and Hyde City

Edinburgh World Heritage Heritage Trails Edinburgh in the time of the Victorians: The Jekyll and Hyde City The look of Old Edinburgh changed greatly during Victorian times, as the city itself underwent big changes during this period of rapid industrial, technological and social development. The 19th century was marked by a period of wealth and prosperity for Edinburgh that it had never experienced before. The whole city was changing but there were two sides to this story. It also became a time of great inequality as the rich got richer and the poor were left increasingly far behind. This, in turn, led to some of the greatest improvers and philanthropists coming to the fore to try to redress that imbalance. Much of the city we see now looks very similar to the way it did in the Victorian period and is one of the reasons why Edinburgh is such a special place to visit. It is one of the reasons why it is a designated World Heritage site and why it needs to be cared for and preserved. The following is a suggested trail route that you could take from the Castle. Do bear in mind that the Mile is frequently very busy and this trail will try to avoid areas that are already congested. However, at certain times of the year it may be impractical to take a large group to some areas - especially at the Castle and near the top of the Mile Please note • These notes are intended as guidelines for teachers, and not as a formal ‘script’ to be followed to the letter. -

WILLIAMSON's DIRECTORY for the City of Edinburgh, Canongate, Leith, and Suburbs

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/williamsonsdirec1773dire THE EDINBURGH DIRECTORY For The Year 1773-4. c^ &*' This reprint is limited to 170 copies, of which 155 are for sale. No.-/4-J WILLIAMSON'S DIRECTORY CITY OF EDINBURGH, CANONGATE, LEITH, AND SUBURBS, From the 25TH May 1773, to 25TH May 1774, BEING THE FIRST PUBLISHED. REPRINTED IN EXACT FACSIMILE, WITH A PREFATORY NOTE. WILLIAM BROWN, 26 PRINCES STREET, EDINBURGH. 1889. PUBLISHER'S NOTE. There has long been considerable dubiety, even in the minds of those most intimately acquainted with the history and antiquities of the city, as to the year in which the first Edinburgh Directory appeared. This has been partly due to the extreme rarity of the volume in question, and partly to the am- biguity of the advertisement on the cover of the Directory for 1775-6—itself very rare—in which it is stated that " the Edinburgh Directory has now been published for three years," without its being made clear whether or not the issue of that year is taken into account. It therefore seems fitting to preface this facsimile reprint of the first edition by a few words as to the discovery of its original, the evidence of its being the first, and the circumstances connected with the publication of the book by Peter Williamson in 1773. The original volume, which is here reproduced by photo-lithography, was purchased by me in London in the present year at the sale of the library of a Scottish collector.