Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks Theme Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Sword to Bury

No Sword to Bury Japanese Americans in Hawai'i during World War II Author's Talk and Book Signing by Franklin Odo Presented by Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project Wednesday, March 10, 2004, 7:00 pm Northwest Asian American Theatre 409 Seventh Avenue South, Seattle "Franklin Odo has captured with much warmth and poignancy the emotions of men who, though abandoned by their country, loved this country and proved it by repeatedly standing in harm's way to defend it." —Senator Daniel K. Inouye When bombs rained down on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Japanese American college students were among the many young men enrolled in ROTC and were called upon to defend the islands immediately after the attack. In a matter of weeks, however, the military government questioned their loyalty and disarmed them. In No Sword to Bury, Franklin Odo places the largely untold story of the wartime experience of these young men in the context of the community created by their immigrant families and its relationship to the larger, white-dominated society. At the heart of the book are vivid oral histories that recall the young men's service on the home front in the Varsity Victory Volunteers, a non-military group dedicated to public works, as well as in the segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team that fought in Europe and the Military Intelligence Service. Odo shows how their wartime experiences and their postwar success in business and politics contributed to the simplistic view of Japanese Americans as a model minority in Hawai'i and glossed over significant differences in their lives and perspectives. -

Iranian-American's Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination

Interpersona | An International Journal on Personal Relationships interpersona.psychopen.eu | 1981-6472 Articles Iranian-American’s Perceptions of Prejudice and Discrimination: Differences Between Muslim, Jewish, and Non-Religious Iranian-Americans Shari Paige* a, Elaine Hatfield a, Lu Liang a [a] University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA. Abstract Recent political events have created a political and social climate in the United States that promotes prejudice against Middle Eastern, Iranian, and Muslim peoples. In this study, we were interested in investigating two major questions: (1) How much ethnic harassment do Iranian-American men and women from various religious backgrounds (Muslim, Jewish, or no religious affiliation at all) perceive in their day-to-day interactions? (2) To what extent does the possession of stereotypical Middle Eastern, Iranian, or Muslim traits (an accent, dark skin, wearing of religious symbols, traditional garb, etc.) spark prejudice and thus the perception of ethnic harassment? Subjects were recruited from two very different sources: (1) shoppers at grocery stores in Iranian-American neighborhoods in Los Angeles, and (2) a survey posted on an online survey site. A total of 338 Iranian-Americans, ages 18 and older, completed an in-person or online questionnaire that included the following: a request for demographic information, an assessment of religious preferences, a survey of how “typically” Iranian-American Muslim or Iranian-American Jewish the respondents’ traits were, and the Ethnic Harassment Experiences Scale. One surprise was that, in general, our participants reported experiencing a great deal of ethnic harassment. As predicted, Iranian-American Muslim men perceived the most discrimination—far more discrimination than did American Muslim women. -

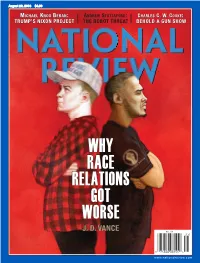

The Democrats Unite Handily

20160829_postal_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/9/2016 6:40 PM Page 1 August 29, 2016 $4.99 MICHAELICHAEL KNOX BERAN:: ANDREW STUTTAFORD: CHARLES C. W. COOKE:: TRUMP’S NIXON PROJECT THE ROBOT THREAT BEHOLD A GUN SHOW WHY RACE RELATIONS GOT WORSEJ.J. D.D. VANCE VANCE www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 7/11/2016 3:41 PM Page 1 NATIONAL REVIEW INSTITUTE ANNOUNCES THE 3rd Annual HONORING SECRETARY GEORGE P. SHULTZ FOR HIS ROLE IN DEFEATING COMMUNISM WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN POLITICAL THOUGHT MICHAEL W. GREBE THE LYNDE AND HARRY BRADLEY FOUNDATION WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR. PRIZE FOR LEADERSHIP IN SUPPORTING LIBERTY THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 CITY HALL SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA For his entire life, Bill Buckley sought to preserve and buttress the foundations of our free society. To honor his achievement and inspire others, National Review Institute’s Board of Trustees has created the William F. Buckley Jr. Prizes for Leadership in Political Thought and Leadership in Supporting Liberty. We hope you will join us this year in San Francisco to support the National Review mission. For reservations and additional information contact Alexandra Zimmern, National Review Institute, at 212.849.2858 or www.nrinstitute.org/wfbprize www.nrinstitute.org National Review Institute (NRI) is the sister nonprofit educational organization of the National Review magazine. NRI is a qualified 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. EIN#13-3649537 TOC-new_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/10/2016 2:43 PM Page 1 Contents AUGUST 29, 2016 | VOLUME LXVIII, NO. 15 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 23 Stephen D. -

Iranian-Americans in Orange County, California: a Survey of Socioeconomic, Attitudinal, and Demographic Characteristics ______

IRANIAN-AMERICANS IN ORANGE COUNTY, CALIFORNIA: A SURVEY OF SOCIOECONOMIC, ATTITUDINAL, AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology ____________________________________ By Daniel Dariush Tanara Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Berna Torr, Chair Professor Eileen Walsh, Department of Sociology Professor Anthony Alvarez, Department of Sociology Fall, 2017 ABSTRACT The latest data from US Census (2013) estimate the Iranian immigrant population at 470,000 in the US and 215,000 (46%) in California. Los Angeles County has the highest concentration of Iranian immigrants population. Orange County, adjacent to L.A. County, is the second largest concentration of Iranian immigrants with estimated population of 36,000. Unfortunately not much is known about this small group of immigrants beyond the basic demographics provided by the census data. Census data suggest that Iranian immigration continue to grow. The preferred destination for most is Orange County, specifically south Orange County that is the most affluent section of the County. In order to better understand the characteristics of this growing immigrant population, I conducted a pilot study of the socioeconomic and attitudinal characteristics of the Iranian immigrant population in city of Mission Viejo in Orange County. The scope of the study was limited mainly due to budget constraints, however, the purpose of the study is not just to collect data, but provide guidelines for more comprehensive, larger study/ies. The data were collected via an online survey in both English and Persian, that included questions outside the scope of the Census, including religions and religiosity, political affiliation, civic engagement, health, and sexual orientation, as well as basic demographics (e.g., age, gender, marital status, etc.) of 1st, 1.5, and 2nd generations of the Iranian immigrants. -

Pars Equality Center V. Trump

Case 1:17-cv-00255-TSC Document 35 Filed 03/15/17 Page 1 of 3 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA PARS EQUALITY CENTER, IRANIAN Civil Action No. 1:17-cv-255 AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION, NATIONAL IRANIAN AMERICAN Hon. Tanya S. Chutkan COUNCIL, PUBLIC AFFAIRS ALLIANCE OF IRANIAN AMERICANS, INC., et al., Plaintiffs, v. DONALD J. TRUMP et al., Defendants. PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Plaintiffs1—individual Iranian nationals and four national Iranian-American organizations—hereby move for a preliminary injunction as set forth below and for the reasons set forth in the accompanying Memorandum of Law in Support of Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction (“Memorandum”). See Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(a). Plaintiffs seek to enjoin Defendants from enforcing or implementing certain provisions of President Donald J. Trump’s Executive Order No. 13,780, entitled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States.” As demonstrated in the Memorandum, the Executive Order and Defendants’ 1 This Motion for a preliminary injunction is filed, by and through undersigned counsel, on behalf of organizational Plaintiffs Pars Equality Center, Iranian American Bar Association, National Iranian American Council and Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans, Inc. as well as individual Plaintiffs Ali Asaei, Shiva Hissong, John Doe #1, John Doe #3, John Doe #5, on behalf of himself and his minor child Baby Doe #1, John Doe #7, John Doe #8, Jane Doe #1, Jane Doe #4, Jane Doe #8, Jane Doe #9, Jane Doe #10, Jane Doe #11, Jane Doe #12, and Jane Doe #13. -

20200130 USCCR Statement on Iranian Americans

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Expresses Concern Over Treatment of Iranian Americans January 30, 2020 The U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, by unanimous vote, expresses deep concern over the treatment of Iranians and Iranian Americans in airports, and calls on the Department of Homeland Security to take all necessary steps immediately to ensure equitable treatment of all people at America’s borders and on the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties to investigate reports of discriminatory treatment of Iranians and Iranian Americans at our borders and within the United States. In early 2020, news reports emerged of Iranians – including American citizens who are of Iranian descent – who were subjected to particular and intense scrutiny by Customs and Border Patrol agents.1 This is in addition to the multiple news reports of Iranians with valid visas who were subjected to similar scrutiny, and in some instances barred from actually entering the United States.2 Further, it seems that these actions are not based on any particularized suspicion or security risk.3 Accordingly, these reports 1 Zolan Kanno-Youngs, Mike Baker, and Mariel Padilla, “U.S. Stops Dozens of Iranian-Americans Returning From Canada,” New York Times, Jan. 5, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/05/us/politics/iranian-americans-border.html; Lloyd Grove, “Iran- Born Ivy League Professor Detained and Grilled About Soleimani at JFK,” The Daily Beast, Jan. 6, 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/iranian-americans-detained-and-grilled-at-us-checkpoints-after-trump- kills-soleimani. 2 Caleb Hampton and Caitlin Dickerson, “‘Demeaned and Humiliated’: What Happened to These Iranians at U.S. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Asian American Collective

Christine R. Yano & Neal K. Adolph Akatsuka, editors in collaboration with the Asian American Collective AsiAn AmericAn college students in Their Own Words STRAIGHT A’s Christine r. Yano and neal K. adolph aKatsuKa, editors in collaboration with the Asian American Collective (aac) Joan Zhang (head) / Claudine Cho / Amy Chyao Shannen Kim / Brooke Nowakowski McCallum Min- Woo Park / Lee Ann Song / Helen Zhao with contributions by Josephine Kim, Franklin Odo, and Jeannie Park AsiAn AmericAn college students in their own words Frontmatter TPTitle, TPSub, TPPub: Position on recto opposite TPAu. A13.04 TPTitle | 75 pt TheSans C4s Semibold small caps, lsp 20, center. sttraigh Align to line 4. A: Yano_TPTitle_A.pdf, place at 100%. ‘S: Flush right, align to line ’s 10. A13.05 TPSubtitle | 12 pt TheSans C4s Bold, small caps, lsp 60, center. 3p left indent. Align to line 28. Color: Drop out. A13.13 TPPub | 9.7/14 Arno Pro Italic, center. Align to line 36. A13.14 TPCities | Starts new line. 9.7 pt Arno Pro sc, lsp 20. A13.15 TPDate | Os figs. Run in after TPCities. Preceeded by word#, solidus, word#. AsiAn AmericAn college students in their own words Duke University Press Durham and London / 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Arno Pro and TheSans by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Yano, Christine Reiko, editor. | Akatsuka, Neal K. Adolph, [date] editor. Title: Straight A’s : Asian American college students in their own words / Christine R. -

Legislative Updates Eriade Hunter

The Modern American Volume 2 Article 11 Issue 1 Spring 2006 2006 Legislative Updates Eriade Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/tma Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Hunter, Eriade. “Legislative Updates.” The odeM rn American, Spring 2006, 35. This Legislative Updates is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in The odeM rn American by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Legislative Updates Keywords Civil Rights Amendments Act of 2005, African-Americans Act, Medicaid Obesity Treatment Act of 2005, Condemning bigotry, violence, and discrimination against Iranian-Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Higher Education Enhancement Act This legislative updates is available in The odeM rn American: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/tma/vol2/iss1/11 LEGISLATIVE UPDATES By Eriade Hunter* H. R. 288 Civil Rights Amendments Act of 2005 S. 2160 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Higher Introduced by Representative Towns (D-NY) Education Enhancement Act This bill will amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Introduced by Senator Boxer (D-CA) Fair Housing Act to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex- This bill aims to amend the Higher Education Act of 1965 ual orientation and will be known as the “Civil Rights Amend- to include Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. -

Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Geography Honors Projects Geography Department 4-26-2017 Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/geography_honors Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Walker-Jones, Delia, "Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity" (2017). Geography Honors Projects. 52. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/geography_honors/52 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geography Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Conference of the Birds: Iranian-Americans, Ethnic Business, and Identity Delia Walker-Jones Macalester College Advisor: Professor Holly Barcus Geography Department 04/26/2017 CONFERENCE OF THE BIRDS 1 Abstract The United States is home to the largest population of Iranians outside of Iran, an immigrant group that slowly emerged over the latter half of the 20th century, spurred by the 1979 Iranian Revolution and subsequent unrest in the mid-2000s. This case study explores the Iranian and Iranian-American-identifying population of the United States, with a geographic focus on the Twin Cities metro area in Minnesota. It delves into several -

Hawai'i's Japanese Americans and National Public Representation

Hawai’i’s Japanese Americans and National Public Representation Franklin Odo Public history, including art history – and specifically public history in museums – is only one of the influential venues through which we derive our sense of our collective “place” in society. Certainly television and film as well as formal schooling are more important in terms of direct impact on social perceptions of ethnicity, race, and gender. But in spite of considerable shifts in recent museum leadership attitudes, museums themselves continue to be regarded as temples of truth and beauty, arbiters of objective history and aesthetic sensibilities. As a result, museums continue to be important influences in shaping social attitudes. Many people do go to museums, at the least for the mandatory field trips in elementary grades, but also for a wide variety of personal reasons. And those who do attend regularly tend to be individuals and groups with considerable authority, including teachers leading these field trips, who validate and authenticate interpretations provided by the museums. It is useful to recall that, while students may go to museums only a few times in their careers, teachers do so on a regular basis and are exposed repeatedly to this particular influence. Other opinion-shapers, including those in the media and the ranks of society’s leaders, absorb and transmit museum notions of beauty and value as well as historical truth through interlocking networks of community councils such as chambers of commerce, school boards and ethnic associations. Thus, museum representations are critical sites that help define who and what make up our society and how we came to be the way we are. -

Counseling with Iranian-Americans: a Critical Review of the Literature

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2014 Counseling with Iranian-Americans: a critical review of the literature Crystal Saidi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Saidi, Crystal, "Counseling with Iranian-Americans: a critical review of the literature" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 437. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/437 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology COUNSELING WITH IRANIAN-AMERICANS: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Crystal Saidi May, 2014 Miguel Gallardo, Psy.D.-Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Crystal Saidi under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Doctoral Committee: Miguel Gallardo, Psy.D., Chairperson Shelly Harrell, Ph.D. Negar Shekarabi, Psy.D. © Copyright by Crystal Saidi (2014) All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION…