John Stanton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623 Matthew R. Laird College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Matthew R., ""In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625691. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dbem-8k64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •'IN THE HOLLOW LOTOS-LAND": DISCORD, ORDER, AND THE EMERGENCE OF STABILITY IN EARLY BERMUDA, 1609-1623 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Matthew R. Laird 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Matthew R. Laird Approved, July 1991 -Acmy James Axtell Thaddeus W. Tate TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................... iv ABSTRACT...............................................v HARBINGERS....... ,.................................... 2 CHAPTER I. MUTINY AND STARVATION, 1609-1615............. 11 CHAPTER II. ORDER IMPOSED, 1615-1619................... 39 CHAPTER III. THE FOUNDATIONS OF STABILITY, 1619-1623......60 A PATTERN EMERGES.................................... -

The Pound Sterling

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 13, February 1952 THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New Jersey The present essay is the thirteenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics and Social Institutions in Princeton University. The author, R. F. Harrod, is joint editor of the ECONOMIC JOURNAL, Lecturer in economics at Christ Church, Oxford, Fellow of the British Academy, and• Member of the Council of the Royal Economic So- ciety. He served in the Prime Minister's Office dur- ing most of World War II and from 1947 to 1950 was a member of the United Nations Sub-Committee on Employment and Economic Stability. While the Section sponsors the essays in this series, it takes no further responsibility for the opinions therein expressed. The writer's are free to develop their topics as they will and their ideas may or may - • v not be shared by the editorial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD Christ Church, Oxford I. PRESUPPOSITIONS OF EARLY POLICY S' TERLING was at its heyday before 1914. It was. something ' more than the British currency; it was universally accepted as the most satisfactory medium for international transactions and might be regarded as a world currency, even indeed as the world cur- rency: Its special position waS,no doubt connected with the widespread ramifications of Britain's foreign trade and investment. -

Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

risks Article Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data Long Hai Vo 1,2 and Duc Hong Vo 3,* 1 Economics Department, Business School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration, Quy Nhon University, Binh Dinh 560000, Vietnam 3 Business and Economics Research Group, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City 7000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Long-range dependency of the volatility of exchange-rate time series plays a crucial role in the evaluation of exchange-rate risks, in particular for the commodity currencies. The Australian dollar is currently holding the fifth rank in the global top 10 most frequently traded currencies. The popularity of the Aussie dollar among currency traders belongs to the so-called three G’s—Geology, Geography and Government policy. The Australian economy is largely driven by commodities. The strength of the Australian dollar is counter-cyclical relative to other currencies and ties proximately to the geographical, commercial linkage with Asia and the commodity cycle. As such, we consider that the Australian dollar presents strong characteristics of the commodity currency. In this study, we provide an examination of the Australian dollar–US dollar rates. For the period from 18:05, 7th August 2019 to 9:25, 16th September 2019 with a total of 8481 observations, a wavelet-based approach that allows for modelling long-memory characteristics of this currency pair at different trading horizons is used in our analysis. -

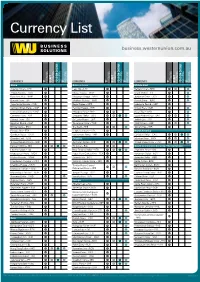

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Coral Reefs, Unintentionally Delivering Bermuda’S E-Mail: [email protected] fi Rst Colonists

Introduction to Bermuda: Geology, Oceanography and Climate 1 0 Kathryn A. Coates , James W. Fourqurean , W. Judson Kenworthy , Alan Logan , Sarah A. Manuel , and Struan R. Smith Geographic Location and Setting Located at 32.4°N and 64.8°W, Bermuda lies in the northwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is isolated by distance, deep Bermuda is a subtropical island group in the western North water and major ocean currents from North America, sitting Atlantic (Fig. 10.1a ). A peripheral annular reef tract surrounds 1,060 km ESE from Cape Hatteras, and 1,330 km NE from the islands forming a mostly submerged 26 by 52 km ellipse the Bahamas. Bermuda is one of nine ecoregions in the at the seaward rim of the eroded platform (the Bermuda Tropical Northwestern Atlantic (TNA) province (Spalding Platform) of an extinct Meso-Cenozoic volcanic peak et al. 2007 ) . (Fig. 10.1b ). The reef tract and the Bermuda islands enclose Bermuda’s national waters include pelagic environments a relatively shallow central lagoon so that Bermuda is atoll- and deep seamounts, in addition to the Bermuda Platform. like. The islands lie to the southeast and are primarily derived The Bermuda Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends from sand dune formations. The extinct volcano is drowned approx. 370 km (200 nautical miles) from the coastline of the and covered by a thin (15–100 m), primarily carbonate, cap islands. Within the EEZ, the Territorial Sea extends ~22 km (Vogt and Jung 2007 ; Prognon et al. 2011 ) . This cap is very (12 nautical miles) and the Contiguous Zone ~44.5 km (24 complex, consisting of several sets of carbonate dunes (aeo- nautical miles) from the same baseline, both also extending lianites) and paleosols laid down in the last million years well beyond the Bermuda Platform. -

Problems of the Sterling Area with Special Reference to Australia

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 17, September 1953 PROBLEMS OF THE STERLING AREA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO AUSTRALIA SIR DOUGLAS COPLAND INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New Jersey This essay was prepared as the *seventeenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Depart- ment of Economics and Social Institutions in Prince- ton University. The author, Sir Douglas Copland, is an Austral- ian economist and was formerly Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University. At present he is Australian High Commissioner in Canada. The views he expresses here do not purport to reflect those of his Government. The Section sponsors the essays in this series but it takes no further responsibility for the opinions expressed in them. The writers are free to develop their topics as they will and their ideas may or may not be shared by the editarial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 17, September 1953 PROBLEMS OF THE STERLING AREA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO AUSTRALIA SIR DOUGLAS COPLAND INTERNATIONAL/ FINANCE SECTION • DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton,- New Jersey 9 PROBLEMS OF THE STERLING AREA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO AUSTRALIA SIR DOUGLAS COPLAND I. INTRODUCTION N the latter stages of the 1939-45 war, when policies were being evolved for a united world operating through a new and grand Iconception of a United Nations and its agencies, plans for coopera- tive action on the economic front, in international finance and trade, were discussed with much fervour and hope. -

Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants Alyssa V

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2016 Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants Alyssa V. Pietraszek University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Recommended Citation Pietraszek, Alyssa V., "Environmental Impacts on the Success of Bermuda's Inhabitants" (2016). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 493. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/493http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/493 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Page 1 Introduction. Since the discovery of the island in 1505, the lifestyle of the inhabitants of Bermuda has been influenced by the island’s isolated geographic location and distinctive geological setting. This influence is visible in nearly every aspect of Bermudian society, from the adoption of small- scale adjustments, such as the collection of rainwater as a source of freshwater and the utilization of fishing wells, to large-scale modifications, such as the development of a maritime economy and the reliance on tourism and international finances. These accommodations are the direct consequences of Bermuda’s environmental and geographic setting and are necessary for Bermudians to survive and prosper on the island. Geographic, Climatic, and Geological Setting. Bermuda is located in the North Atlantic Ocean at 32º 20’ N, 64º 45’ W, northwest of the Sargasso Sea and around 1000 kilometers southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Vacher & Rowe, 1997). -

Standard Settlement Instructions for Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments

Standard Settlement Instructions For Foreign Exchange, Money Market and Commercial Payments CURRENCY CORRESPONDENT BANK S.W.I.F.T ADDRESS Australian Dollar Westpac Banking Corporation WPACAU2S AUD Sydney, Australia Barbados Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Bridgetown NOCSBBBB BBD Barbados Bermudian Dollar The Bank of N. T. Butterfield & Son Ltd. BNTBBMHM BMD Hamilton, Bermuda Bahamian Dollar Scotiabank (Bahamas) Ltd. NOSCBSNS BSD Nassau, Bahamas Belize Dollar Scotiabank (Belize) Ltd., NOSCBZBS BZD Belize City, Belize Canadian Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCCATT CAD International Banking Division, Toronto Cyprus Pound Bank of Cyprus Public Company Ltd., BCYPCY2N010 CYP Nicosia, Cyrpus Czech Koruna Ceskolovenska Obchodni Banka A.S. CEKOCZPP CZK Prague Danish Krone Nordea Bank Danmark A/S NDEADKKK DKK Copenhagen, Denmark Euro Deutsche Bank AG DEUTDEFF EUR Frankfurt Fiji Dollar Wetspac Banking Corporation WPACFJFX FJD Suva, Fiji Guyana Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia, Georgetown, NOSCGYGE GYD Guyana Hong Kong Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCHKHH HKD Hong Kong Hungarian Forint MKB Bank ZRT MKKB HU HB HUF Indian Rupee The Bank of Nova Scotia NOSCINBB INR Mumbai Indonesian Rupiah Standard Chartered Bank SCBLIDJX IDR Jakarta, Indonesia Israeli Sheqel Bank Hapaolim BM POALILIT ILS Tel Aviv Jamaican Dollar The Bank of Nova Scotia Jamaica Ltd. NOSCBSNSKIN JMD Kingston, Jamaica Japanese Yen The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. BOTKJPJT JPY Tokyo Cayman Islands Dollar Scotiabank and Trust (Cayman) Ltd. NOSCKYKX KYD Cayman Islands Malaysian -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Bermuda Tourism Authority

CITY OF HAMILTON* I4-2VI Bermuda Chamber of Commerce •C> At Ferry Terminal C'-tf □ mmmM Alexandra Battery Par* R 2 Old Military Rd Bermuda Tourism Authority Fire Department Cake Cpmpany NW Ranjparts^^?*-* nAI Orange Valley Rd J 8 BERMUDA ■'.l ' a ,sible Blue Hole Park Bermuda Historical Society Museum Fort Hamilton K-.2 m • Botanical Gardens SB jft.9§ Old Rd L 5 : Toilets only Bermuda Monetary Authority Perot Post Office £■>5; Bermuda jcoolw ■ V A S Lifeguard o: Castle Island Nature Res .R..S$ Paynters Rd ,n duly (su .o Bermuda National Library ,C.i- 4/. Police Station . H-m. Cfayworks Ron£, ^ Coney Island Park B Ni'3i Pepper Hall Rd R 3 ROYAL NAVAL Beaches Jiays Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity ..iff* 3? Post Office (General) . G3 ^ * 00 Arts Centre Cooper's Island Nature Res in! R 4 Radnor Rd L S <*>5^- Royal Bermuda Yacht Club ; „ Moped Achilles Bay ..lAi Cenotaph & The Cabinet Building 8 & DOCKYARD Crawl Waterfront Park Retreat Hill 0 t SIpSEuousE a ac - Scooter Ql City Hall & Arts Centre 0 . Sessions House (Supreme Court) r,tsjift so (7«ij Annie's Bay Devonshire Bay Park Sayle Rd .L 8 S3 b ?|gsv ? VC Bailey's Bay Devonshire Marsh St. David’s Rd Q 3 Olocktdwor |fc (WMC'W.i) : >■ ■■ ■ I'm r ' * NATIONAL MUSEUM Blue Hole Ducks Puddle Park St. Mark's Rd L 7 ftnratT. " oUJ OF BERMUDA - sW9m wketri Building Bay Ferry Point Park H Secretary Rd Q 1 ■ Clearwater Beach QSS Great Head Park. Sornmersall Rd . Nrt£$ C3 Beach house with facilities fflS Devi's Hole Higgs & Horse-shoe Island Southside Rd Q 3 Daniel's Head Park. -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used.