Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dividend Policy and Share Price Volatility”

“Dividend policy and share price volatility” Sew Eng Hooi AUTHORS Mohamed Albaity Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy Sew Eng Hooi, Mohamed Albaity and Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy (2015). Dividend ARTICLE INFO policy and share price volatility. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 12(1-1), 226-234 RELEASED ON Tuesday, 07 April 2015 JOURNAL "Investment Management and Financial Innovations" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Volume 12, Issue 1, 2015 Sew Eng Hooi (Malaysia), Mohamed Albaity (Malaysia), Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy (Malaysia) Dividend policy and share price volatility Abstract The objective of this study is to examine the relationship between dividend policy and share price volatility in the Malaysian market. A sample of 319 companies from Kuala Lumpur stock exchange were studied to find the relationship between stock price volatility and dividend policy instruments. Dividend yield and dividend payout were found to be negatively related to share price volatility and were statistically significant. Firm size and share price were negatively related. Positive and statistically significant relationships between earning volatility and long term debt to price volatility were identified as hypothesized. However, there was no significant relationship found between growth in assets and price volatility in the Malaysian market. Keywords: dividend policy, share price volatility, dividend yield, dividend payout. JEL Classification: G10, G12, G14. Introduction (Wang and Chang, 2011). However, difference in tax structures (Ho, 2003; Ince and Owers, 2012), growth Dividend policy is always one of the main factors and development (Bulan et al., 2007; Elsady et al., that an investor will focus on when determining 2012), governmental policies (Belke and Polleit, 2006) their investment strategy. -

Putting Volatility to Work

Wh o ’ s afraid of volatility? Not anyone who wants a true edge in his or her trad i n g , th a t ’ s for sure. Get a handle on the essential concepts and learn how to improve your trading with pr actical volatility analysis and trading techniques. 2 www.activetradermag.com • April 2001 • ACTIVE TRADER TRADING Strategies BY RAVI KANT JAIN olatility is both the boon and bane of all traders — The result corresponds closely to the percentage price you can’t live with it and you can’t really trade change of the stock. without it. Most of us have an idea of what volatility is. We usually 2. Calculate the average day-to-day changes over a certain thinkV of “choppy” markets and wide price swings when the period. Add together all the changes for a given period (n) and topic of volatility arises. These basic concepts are accurate, but calculate an average for them (Rm): they also lack nuance. Volatility is simply a measure of the degree of price move- Rt ment in a stock, futures contract or any other market. What’s n necessary for traders is to be able to bridge the gap between the Rm = simple concepts mentioned above and the sometimes confus- n ing mathematics often used to define and describe volatility. 3. Find out how far prices vary from the average calculated But by understanding certain volatility measures, any trad- in Step 2. The historical volatility (HV) is the “average vari- er — options or otherwise — can learn to make practical use of ance” from the mean (the “standard deviation”), and is esti- volatility analysis and volatility-based strategies. -

Explainer: Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy

rba.gov.au/education twitter.com/RBAInfo facebook.com/ ReserveBankAU/ Exchange Rates and the youtube.com /user/RBAinfo Australian Economy An exchange rate is the value of one currency in Together these effects also have implications for terms of another currency. Exchange rates matter the balance of payments. This Explainer describes to Australia’s economy because of their influence the effects of exchange rate movements and on trade and financial flows between Australia highlights the main channels through which and the rest of the world. Changes in exchange these changes affect the Australian economy. rates affect the Australian economy in two If the exchange rate between the Australian dollar main ways: and the US dollar is 0.75 then one Australian 1 There is a direct effect on the prices of dollar can be converted into US75c. An increase goods and services produced in Australia in the value of the Australian dollar is called relative to the prices of goods and services an appreciation. A decrease in the value of the produced overseas. Australian dollar is known as a depreciation. 2 There is an indirect effect on economic activity and inflation as changes in the relative prices of goods and services produced domestically and overseas influence decisions about production and consumption. Exchange rates and economic activity Trade prices Economic activity and inflation GDP Export Export prices volumes Exchange Domestic Unemployment Inflation rate demand Import Import prices volumes RESERVE BANK OF AUSTRALIA | Education Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy 1 Australian goods and services, leading to an Direct Effects increase in the volume (that is, quantity) of The direct effect of an exchange rate movement Australian exports. -

FX Effects: Currency Considerations for Multi-Asset Portfolios

Investment Research FX Effects: Currency Considerations for Multi-Asset Portfolios Juan Mier, CFA, Vice President, Portfolio Analyst The impact of currency hedging for global portfolios has been debated extensively. Interest on this topic would appear to loosely coincide with extended periods of strength in a given currency that can tempt investors to evaluate hedging with hindsight. The data studied show performance enhancement through hedging is not consistent. From the viewpoint of developed markets currencies—equity, fixed income, and simple multi-asset combinations— performance leadership from being hedged or unhedged alternates and can persist for long periods. In this paper we take an approach from a risk viewpoint (i.e., can hedging lead to lower volatility or be some kind of risk control?) as this is central for outcome-oriented asset allocators. 2 “The cognitive bias of hindsight is The Debate on FX Hedging in Global followed by the emotion of regret. Portfolios Is Not New A study from the 1990s2 summarizes theoretical and empirical Some portfolio managers hedge papers up to that point. The solutions reviewed spanned those 50% of the currency exposure of advocating hedging all FX exposures—due to the belief of zero expected returns from currencies—to those advocating no their portfolio to ward off the pain of hedging—due to mean reversion in the medium-to-long term— regret, since a 50% hedge is sure to and lastly those that proposed something in between—a range of values for a “universal” hedge ratio. Later on, in the mid-2000s make them 50% right.” the aptly titled Hedging Currencies with Hindsight and Regret 3 —Hedging Currencies with Hindsight and Regret, took a behavioral approach to describe the difficulty and behav- Statman (2005) ioral biases many investors face when incorporating currency hedges into their asset allocation. -

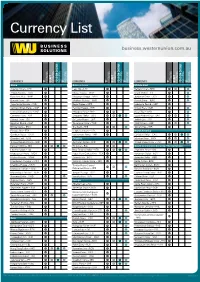

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

There's More to Volatility Than Volume

There's more to volatility than volume L¶aszl¶o Gillemot,1, 2 J. Doyne Farmer,1 and Fabrizio Lillo1, 3 1Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM 87501 2Budapest University of Technology and Economics, H-1111 Budapest, Budafoki ut¶ 8, Hungary 3INFM-CNR Unita di Palermo and Dipartimento di Fisica e Tecnologie Relative, Universita di Palermo, Viale delle Scienze, I-90128 Palermo, Italy. It is widely believed that uctuations in transaction volume, as reected in the number of transactions and to a lesser extent their size, are the main cause of clus- tered volatility. Under this view bursts of rapid or slow price di®usion reect bursts of frequent or less frequent trading, which cause both clustered volatility and heavy tails in price returns. We investigate this hypothesis using tick by tick data from the New York and London Stock Exchanges and show that only a small fraction of volatility uctuations are explained in this manner. Clustered volatility is still very strong even if price changes are recorded on intervals in which the total transaction volume or number of transactions is held constant. In addition the distribution of price returns conditioned on volume or transaction frequency being held constant is similar to that in real time, making it clear that neither of these are the principal cause of heavy tails in price returns. We analyze recent results of Ane and Geman (2000) and Gabaix et al. (2003), and discuss the reasons why their conclusions di®er from ours. Based on a cross-sectional analysis we show that the long-memory of volatility is dominated by factors other than transaction frequency or total trading volume. -

Futures Price Volatility in Commodities Markets: the Role of Short Term Vs Long Term Speculation

Matteo Manera, a Marcella Nicolini, b* and Ilaria Vignati c Futures price volatility in commodities markets: The role of short term vs long term speculation Abstract: This paper evaluates how different types of speculation affect the volatility of commodities’ futures prices. We adopt four indexes of speculation: Working’s T, the market share of non-commercial traders, the percentage of net long speculators over total open interest in future markets, which proxy for long term speculation, and scalping, which proxies for short term speculation. We consider four energy commodities (light sweet crude oil, heating oil, gasoline and natural gas) and six non-energy commodities (cocoa, coffee, corn, oats, soybean oil and soybeans) over the period 1986-2010, analyzed at weekly frequency. Using GARCH models we find that speculation is significantly related to volatility of returns: short term speculation has a positive and significant coefficient in the variance equation, while long term speculation generally has a negative sign. The robustness exercise shows that: i) scalping is positive and significant also at higher and lower data frequencies; ii) results remain unchanged through different model specifications (GARCH-in-mean, EGARCH, and TARCH); iii) results are robust to different specifications of the mean equation. JEL Codes: C32; G13; Q11; Q43. Keywords: Commodities futures markets; Speculation; Scalping; Working’s T; Data frequency; GARCH models _______ a University of Milan-Bicocca, Milan, and Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, Milan. E-mail: [email protected] b University of Pavia, Pavia, and Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, Milan. E-mail: [email protected] c Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, Milan. -

The Cross-Section of Volatility and Expected Returns

THE JOURNAL OF FINANCE • VOL. LXI, NO. 1 • FEBRUARY 2006 The Cross-Section of Volatility and Expected Returns ANDREW ANG, ROBERT J. HODRICK, YUHANG XING, and XIAOYAN ZHANG∗ ABSTRACT We examine the pricing of aggregate volatility risk in the cross-section of stock returns. Consistent with theory, we find that stocks with high sensitivities to innovations in aggregate volatility have low average returns. Stocks with high idiosyncratic volatility relative to the Fama and French (1993, Journal of Financial Economics 25, 2349) model have abysmally low average returns. This phenomenon cannot be explained by exposure to aggregate volatility risk. Size, book-to-market, momentum, and liquidity effects cannot account for either the low average returns earned by stocks with high exposure to systematic volatility risk or for the low average returns of stocks with high idiosyncratic volatility. IT IS WELL KNOWN THAT THE VOLATILITY OF STOCK RETURNS varies over time. While con- siderable research has examined the time-series relation between the volatility of the market and the expected return on the market (see, among others, Camp- bell and Hentschel (1992) and Glosten, Jagannathan, and Runkle (1993)), the question of how aggregate volatility affects the cross-section of expected stock returns has received less attention. Time-varying market volatility induces changes in the investment opportunity set by changing the expectation of fu- ture market returns, or by changing the risk-return trade-off. If the volatility of the market return is a systematic risk factor, the arbitrage pricing theory or a factor model predicts that aggregate volatility should also be priced in the cross-section of stocks. -

Currency Internationalization This Page Intentionally Left Blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi

Currency Internationalization This page intentionally left blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi Edited By Wensheng Peng Chang Shu Introduction, selection, editorial matter, foreword, chapters 5 and 10 © The Monetary Authority appointed pursuant to section 5A of the Exchange Fund Ordinance 2010 Other individual chapters © contributors 2010 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2010 978-0-230-58049-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN 978-1-349-36848-8 ISBN 978-0-230-24578-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230245785 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Australian Dollar/Euro Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar Austrln Dollar

Indexes - The Globe and Mail - December 29, 2017 Company Symbol Last Price 52W 52W 1 Year Vol. Yr High Low % Chg (000) Australian Dollar/Euro AUD/EUR 0.650 0.732 0.635 -5.55 0 Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen AUD/JPY 87.950 90.360 81.480 4.43 0 Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc AUD/CHF 0.761 0.780 0.715 2.97 0 Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar AUD/USD 0.780 0.810 0.716 8.05 0 Austrln Dollar/British Pound AUD/GBP 0.578 0.628 0.557 -1.85 0 Austrln Dollar/Canadian Dollar AUD/CAD 0.981 1.035 0.958 .72 0 Bloomberg Agriculture BCOMAG 47.509 57.517 46.793 -11.82 0 Bloomberg Aluminum BCOMAL 36.091 36.446 27.549 29.71 0 Bloomberg Commodity Index BCOM 88.167 89.448 79.420 .47 0 Bloomberg Energy BCOMEN 38.016 40.496 29.919 -5.66 0 Bloomberg ExEnergy BCOMXE 92.072 94.942 87.357 4.21 0 Bloomberg Gold BCOMGC 158.595 165.548 141.495 10.90 0 Bloomberg Grains BCOMGR 32.640 40.760 32.396 -12.00 0 Bloomberg Industrial Metals BCOMIN 138.510 138.528 107.058 28.29 0 Bloomberg Livestock BCOMLI 30.524 33.513 28.215 5.38 0 Bloomberg Petroleum BCOMPE 312.977 312.977 312.977 .00 0 Bloomberg Precious Metals BCOMPR 174.049 182.964 158.178 8.80 0 Bloomberg Softs BCOMSO 41.824 53.657 38.082 -15.32 0 British Pound/Austrln Dollar GBP/AUD 1.731 1.795 1.593 1.88 0 British Pound/Canadian Dollar GBP/CAD 1.699 1.783 1.585 2.62 0 British Pound/Euro GBP/EUR 1.125 1.203 1.075 -3.75 0 British Pound/Japanese Yen GBP/JPY 152.260 152.870 136.200 6.41 0 British Pound/Swiss Franc GBP/CHF 1.317 1.341 1.224 4.89 0 British Pound/U.S. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

New France (Ca

New France (ca. 1600-1770) Trade silver, beaver, eighteenth century Manufactured in Europe and North America for trade with the Native peoples, trade silver came in many forms, including ear bobs, rings, brooches, gorgets, pendants, and animal shapes. According to Adam Shortt,5 the great France, double tournois, 1610 Canadian economic historian, the first regular Originally valued at 2 deniers, the system of exchange in Canada involving Europeans copper “double tournois” was shipped to New France in large quantities during occurred in Tadoussac in the early seventeenth the early 1600s to meet the colony’s century. Here, French traders bartered each year need for low-denomination coins. with the Montagnais people (also known as the Innu), trading weapons, cloth, food, silver items, and tobacco for animal pelts, especially those of the beaver. Because of the risks associated with In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded transporting gold and silver (specie) across the the first colonial settlement at Quebec on the Atlantic, and to attract and retain fresh supplies of St. Lawrence River. The one universally accepted coin, coins were given a higher value in the French medium of exchange in the infant colony naturally colonies in Canada than in France. In 1664, became the beaver pelt, although wheat and moose this premium was set at one-eighth but was skins were also employed as legal tender. As the subsequently increased. In 1680, monnoye du pays colony expanded, and its economic and financial was given a value one-third higher than monnoye needs became more complex, coins from France de France, a valuation that held until 1717 when the came to be widely used.