Road Freight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explainer: Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy

rba.gov.au/education twitter.com/RBAInfo facebook.com/ ReserveBankAU/ Exchange Rates and the youtube.com /user/RBAinfo Australian Economy An exchange rate is the value of one currency in Together these effects also have implications for terms of another currency. Exchange rates matter the balance of payments. This Explainer describes to Australia’s economy because of their influence the effects of exchange rate movements and on trade and financial flows between Australia highlights the main channels through which and the rest of the world. Changes in exchange these changes affect the Australian economy. rates affect the Australian economy in two If the exchange rate between the Australian dollar main ways: and the US dollar is 0.75 then one Australian 1 There is a direct effect on the prices of dollar can be converted into US75c. An increase goods and services produced in Australia in the value of the Australian dollar is called relative to the prices of goods and services an appreciation. A decrease in the value of the produced overseas. Australian dollar is known as a depreciation. 2 There is an indirect effect on economic activity and inflation as changes in the relative prices of goods and services produced domestically and overseas influence decisions about production and consumption. Exchange rates and economic activity Trade prices Economic activity and inflation GDP Export Export prices volumes Exchange Domestic Unemployment Inflation rate demand Import Import prices volumes RESERVE BANK OF AUSTRALIA | Education Exchange Rates and the Australian Economy 1 Australian goods and services, leading to an Direct Effects increase in the volume (that is, quantity) of The direct effect of an exchange rate movement Australian exports. -

Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data

risks Article Modelling Australian Dollar Volatility at Multiple Horizons with High-Frequency Data Long Hai Vo 1,2 and Duc Hong Vo 3,* 1 Economics Department, Business School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Finance, Banking and Business Administration, Quy Nhon University, Binh Dinh 560000, Vietnam 3 Business and Economics Research Group, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City 7000, Vietnam * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Long-range dependency of the volatility of exchange-rate time series plays a crucial role in the evaluation of exchange-rate risks, in particular for the commodity currencies. The Australian dollar is currently holding the fifth rank in the global top 10 most frequently traded currencies. The popularity of the Aussie dollar among currency traders belongs to the so-called three G’s—Geology, Geography and Government policy. The Australian economy is largely driven by commodities. The strength of the Australian dollar is counter-cyclical relative to other currencies and ties proximately to the geographical, commercial linkage with Asia and the commodity cycle. As such, we consider that the Australian dollar presents strong characteristics of the commodity currency. In this study, we provide an examination of the Australian dollar–US dollar rates. For the period from 18:05, 7th August 2019 to 9:25, 16th September 2019 with a total of 8481 observations, a wavelet-based approach that allows for modelling long-memory characteristics of this currency pair at different trading horizons is used in our analysis. -

Detection and Epidemiology of Coxiella Burnetii Infection in Beef Cattle in Northern Australia and the Potential Risk to Public Health

Detection and epidemiology of Coxiella burnetii infection in beef cattle in northern Australia and the potential risk to public health Caitlin Medhbh Wood BVSc (Hons1) MANZCVS (Veterinary Epidemiology) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2716-0402 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2020 School of Veterinary Science Abstract Q fever has a longstanding history in Queensland, Australia. Although it is not a new disease to Australia, Q fever continues to burden the country with some of the highest annual case notification rates globally (Tozer 2015). While there are undeniable links with Q fever cases and exposure to cattle, it appears that coxiellosis predominantly goes undiagnosed and unnoticed in cattle within Australia. Knowledge of the prevalence and distribution of coxiellosis in cattle populations across northern Australia is limited due to minimal surveillance and no standardisation of diagnostic test methods. The overall aim of this PhD project was to improve the understanding of the epidemiology of coxiellosis in beef cattle in northern Australia and gain insights into the potential risk to public health. Descriptive analyses of 2,838 human Q fever notifications from Queensland between 2003 and 2017 were initially reported. Queensland accounted for 43% of the Australian national Q fever notifications for this period. From 2013–2017 the most common identifiable occupational group was agricultural/farming. For the same period, at-risk environmental exposures were identified in 82% (961/1,170) of notifications; at-risk animal-related exposures were identified in 52% (612/1,170) of notifications; abattoir exposure was identified in 7% of notifications. -

Currency Internationalization This Page Intentionally Left Blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi

Currency Internationalization This page intentionally left blank Currency Internationalization: Global Experiences and Implications for the Renminbi Edited By Wensheng Peng Chang Shu Introduction, selection, editorial matter, foreword, chapters 5 and 10 © The Monetary Authority appointed pursuant to section 5A of the Exchange Fund Ordinance 2010 Other individual chapters © contributors 2010 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2010 978-0-230-58049-7 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries ISBN 978-1-349-36848-8 ISBN 978-0-230-24578-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230245785 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Australian Dollar/Euro Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar Austrln Dollar

Indexes - The Globe and Mail - December 29, 2017 Company Symbol Last Price 52W 52W 1 Year Vol. Yr High Low % Chg (000) Australian Dollar/Euro AUD/EUR 0.650 0.732 0.635 -5.55 0 Australian Dollar/Japanese Yen AUD/JPY 87.950 90.360 81.480 4.43 0 Australian Dollar/Swiss Franc AUD/CHF 0.761 0.780 0.715 2.97 0 Australian Dollar/U.S. Dollar AUD/USD 0.780 0.810 0.716 8.05 0 Austrln Dollar/British Pound AUD/GBP 0.578 0.628 0.557 -1.85 0 Austrln Dollar/Canadian Dollar AUD/CAD 0.981 1.035 0.958 .72 0 Bloomberg Agriculture BCOMAG 47.509 57.517 46.793 -11.82 0 Bloomberg Aluminum BCOMAL 36.091 36.446 27.549 29.71 0 Bloomberg Commodity Index BCOM 88.167 89.448 79.420 .47 0 Bloomberg Energy BCOMEN 38.016 40.496 29.919 -5.66 0 Bloomberg ExEnergy BCOMXE 92.072 94.942 87.357 4.21 0 Bloomberg Gold BCOMGC 158.595 165.548 141.495 10.90 0 Bloomberg Grains BCOMGR 32.640 40.760 32.396 -12.00 0 Bloomberg Industrial Metals BCOMIN 138.510 138.528 107.058 28.29 0 Bloomberg Livestock BCOMLI 30.524 33.513 28.215 5.38 0 Bloomberg Petroleum BCOMPE 312.977 312.977 312.977 .00 0 Bloomberg Precious Metals BCOMPR 174.049 182.964 158.178 8.80 0 Bloomberg Softs BCOMSO 41.824 53.657 38.082 -15.32 0 British Pound/Austrln Dollar GBP/AUD 1.731 1.795 1.593 1.88 0 British Pound/Canadian Dollar GBP/CAD 1.699 1.783 1.585 2.62 0 British Pound/Euro GBP/EUR 1.125 1.203 1.075 -3.75 0 British Pound/Japanese Yen GBP/JPY 152.260 152.870 136.200 6.41 0 British Pound/Swiss Franc GBP/CHF 1.317 1.341 1.224 4.89 0 British Pound/U.S. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

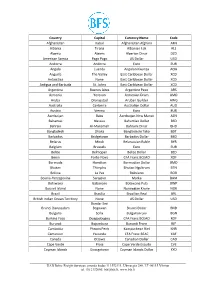

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

THE COMMODITY-CURRENCY VIEW of the AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR: a MULTIVARIATE COINTEGRATION APPROACH I. Introduction

Journal of Applied Economics, Vol. VIII, No. 1 (May 2005), 81-99 THE COMMODITY-CURRENCY VIEW OF THE AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 81 THE COMMODITY-CURRENCY VIEW OF THE AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR: A MULTIVARIATE COINTEGRATION APPROACH * DIMITRIS HATZINIKOLAOU University of Ioannina and METODEY POLASEK Flinders University Submitted November 2002; accepted October 2003 Using Australian quarterly data from the post-float period 1984:1-2003:1 and a partial system, we identify and estimate two cointegrating relations, one for the interest-rate differential and the other for the nominal exchange rate. Our estimate of the long-run elasticity of the exchange rate with respect to commodity prices is 0.939, which strongly supports the widely held view that the floating Australian dollar is a ‘commodity currency’. We also find that the PPP and UIP cannot be rejected so long as commodity prices are included in the cointegrating relations. Our model outperforms the random walk model in forecasting the exchange rate in the medium run. JEL classification codes: F31, F41 Key words: Australian dollar, commodity currency, cointegration I. Introduction In the Australian setting, extraneously determined terms of trade have long been recognized as a variable playing a central role in influencing the country’s economic outcomes (Salter, 1959; Swan, 1960; Gregory, 1976). * Dimitris Hatzinikolaou (corresponding author): University of Ioannina, Department of Economics, 45110 Ioannina, Greece; e-mail: [email protected]. Metodey Polasek: Flinders University, School of Business Economics, Adelaide, GPO Box 2100, S.A. 5001, Australia. We are grateful to an anonymous referee of this journal for his/her constructive comments on an earlier version of the paper. -

Country Profile: Australia Note: Representative

Country Profile: Australia Introduction Australia or the Commonwealth of Australia is located in the Oceania region, consisting of the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and several other smaller islands. Australia or the Commonwealth of Australia is the world's sixth-largest country by total area.Located between the Indian and Pacific oceans, the country is approximately 4,000 km from east to west and 3,200 km from north to south, with a coastline 36,735 km long. Australia has maintained a stable liberal democratic political system that functions as a federal parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy comprising six states and several territories. Note: Representative Map 1 Country Profile: Australia Population Australians come from a rich variety of cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious background. While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the original inhabitants of the land, immigrants from about 200 countries also call Australia home. Until the 1970s, the majority of immigrants to Australia came from Europe. These days Australia receives many more immigrants from Asia, and since 1996 the number of immigrants from Africa and the Middle East has almost doubled1. As per the census of 2015, the total population of Australia was around 23,856,200. The most populous states are New South Wales and Victoria, with their respective capitals, Sydney and Melbourne, the largest cities in Australia. Economy Known as one of the great agricultural, mining and energy producers, Australia has one of the world’s most open and varied economies, with a highly educated workforce and an extensive services sector. -

2018-BBDXY-Index-Rebalance.Pdf

BLOOMBERG DOLLAR INDEX 2018 REBALANCE 2018 REBALANCE HIGHLIGHTS • Euro maintains largest weight 2018 BBDXY WEIGHTS Euro 3.0% Japanese Yen • Canadian dollar largest percentage weight 2.1% 3.7% Canadian Dollar decrease 4.5% 5.1% Mexican Peso • Swiss franc has largest percentage weight increase 31.5% British Pound 10.5% Australian Dollar 10.0% • Mexican peso’s weight continues to increase Swiss Franc 18.0% (2007: 6.98% to 2018: 10.04%) 11.4% South Korean Won Chinese Renminbi Indian Rupee STEPS TO COMPUTE 2018 MEMBERS & WEIGHTS Fed Reserve’s BIS Remove pegged Trade Data Liquidity Survey currencies to USD Remove currency Set Cap exposure Average liquidity positions under to Chinese & trade weights 2% Renminbi to 3% Bloomberg Dollar Index Members & Weights 2018 TARGET WEIGHTS- BLOOMBERG DOLLAR INDEX Currency Name Currency Ticker 2018 Target Weight 2017 Target Weights Difference Euro EUR 31.52% 31.56% -0.04% Japanese Yen JPY 18.04% 17.94% 0.10% Canadian Dollar CAD 11.42% 11.54% -0.12% British Pound GBP 10.49% 10.59% -0.10% Mexican Peso MXN 10.05% 9.95% 0.09% Australian Dollar AUD 5.09% 5.12% -0.03% Swiss Franc CHF 4.51% 4.39% 0.12% South Korean Won KRW 3.73% 3.81% -0.08% Chinese Renminbi CNH 3.00% 3.00% 0.00% Indian Rupee INR 2.14% 2.09% 0.06% GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF MEMBER CURRENCIES GLOBAL 21.47% Americas 46.53% Asia/Pacific 32.01% EMEA APAC EMEA AMER 6.70% 9.70% 9.37% Japanese Yen Australian Dollar Euro Canadian Dollar 46.80% 11.67% South Korean Won 22.56% 56.36% British Pound 53.20% 15.90% 67.74% Mexican Peso Chinese Renminbi Swiss Franc -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

List of BDO Branches Authorized to Exchange Foreign Currencies As of (March 8, 2021)

List of BDO Branches Authorized to Exchange Foreign Currencies as of (March 8, 2021) I. US Dollar (USD) – All BDO Branches II. Other Currencies • Australian Dollar (AUD) • Japanese Yen (JPY) • Bahrain Dinar (BHY) • Korean Won (KRW) • British Pound (GBP) • Saudi Rial (SAR) • Brunei Dollar (BND) • Singapore Dollar (SGD) Chinese Yuan (CNY) • Canadian Dollar (CAD) • Swiss Frank (CHF) • Euro (EUR) • Taiwan Dollar (TWD) • Hongkong Dollar (HKD) • Thailand Baht (THB) • Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) • UAE Dirham (AED) 1 A Place - Coral Way 1 A. Arnaiz – Paseo 2 A. Bonifacio Ave. - Balintawak 2 A. Arnaiz-San Lorenzo Village 3 A. Santos - St. James 3 A. Santos - St. James 4 Acropolis - E. Rodriguez Jr. 4 ADB Avenue Ortigas 5 ADB Avenue Ortigas 5 Alabang Hills 6 Alabang - Madrigal Ave 6 Alabang - Madrigal Ave 7 Angeles City – Miranda 7 Araneta Center Ali Mall II 8 Angono – M.L. Quezon Avenue 8 Arranque 9 Arranque 9 Asia Tower - Paseo 10 Arranque - T. Alonzo 10 Aurora Blvd. - Broadway Centrum 11 Asia Tower - Paseo 11 Aurora Blvd - Notre Dame 12 Aurora Blvd - Broadway Centrum 12 Aurora Blvd. - Yale 13 Aurora Blvd - Notre Dame 13 Ayala Alabang - Richville Center 14 Aurora Blvd. - Yale 14 Ayala Avenue - People Support 15 Ayala Alabang - Richville Center 15 Ayala Avenue - SGV1 Bldg 16 Ayala Avenue - People Support 16 Ayala Triangle 1 17 Ayala Avenue - SGV1 Bldg 17 Baclaran 18 Ayala – Rufino 18 Bacolod – Araneta 19 Baclaran 19 Bacolod - Capitol Shopping 20 Bacolod – Araneta 20 Baguio - Session Road 21 Bacolod - Capitol Shopping 21 Baguio - Marcos Highway Centerpoint 22 Bacolod – Gonzaga 22 Banawe - Agno 23 Bacoor - Aguinaldo Highway 23 Banawe - Amoranto 24 Bagtikan – Chino Roces Avenue 24 Batangas - Sto. -

Download Full Article 456.4KB .Pdf File

Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria 56(2):33 1-337 (1997) 28 February 1997 https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1997.56.21 SPIDERS AS ECOLOGICAL INDICATORS : AN OVERVIEW FOR AUSTRALIA Tracey B. Churchill Arachnology, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300. South Brisbane, Qld 4101, Australia Centre, PMB 44 present address : Division of Wildlife and Ecology, CSIRO Tropical Ecosystems Research Winnellie, NT 0821, Australia Abstract Churchill, T.B., 1997. Spiders as ecological indicators: an overview for Australia. Memoirs of the Museum of Victoria 56(2): 331-337. Spiders operate as a dominant predator complex which can influence the structure of terrestrial invertebrate communities. The potential use of spiders as indicators of ecological to change, amongst a suite of selected taxa, is worthy of further research. Indicator taxa need be diverse and abundant, readily sampled, functionally significant, and to interact with their the environment in a way that can reflect aspects of ecological change. This paper examines proposes attributes of spiders in terms of these criteria, with an Australian perspective, and the use of families as functional groups to represent divergent foraging strategies and selec- "taxonomic tion of prey types. With such information gain, and reduced impact of the collation of impediment", the cost-benefit of surveys is enhanced to encourage the wider quantitative spider data for management or conservation purposes. Introduction mining (Majer, 1983; Andersen, 1990, ms.). To gain a wider understanding of patterns of biod- iversity and ecological change in invertebrate have an important role to play in Invertebrates communities, however, a range of taxa need to achieving effective conservation and manage- be adopted (Beattieetal., 1993; Kitching, 1994; ment of biodiversity for three reasons: New, 1995; Noss, 1990).