Canberra Law Review Volume 16 Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cost of a Cyber Incident)

CO ST OF A CYBER INCIDENT: S YSTEMATIC REVIEW AND C ROSS-VALIDATION OCTOBER 26, 2020 1 Acknowledgements We are grateful to Dr. Allan Friedman, Dr. Lawrence Gordon, Jay Jacobs, Dr. Sasha Romanosky, Matthew Shabat, Kelly Shortridge, Steven Surdu, David Tobar, Brett Tucker and Sounil Yu for the review comments and helpful feedback on the earlier draft of the report. The authors would like to thank CISA staff for support and advice on this project. 2 Table of Contents 1. Objectives .................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Results in Brief .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Analysis ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 3.1. Per-Incident Cost and Loss Estimates .............................................................................................. 18 3.1.1. Cross-Validation: Primary Loss Data for Large and Small Incidents .................................. 20 3.1.2. Reconciliation of Per-Incident Cost Studies .................................................................................. 26 3.1.3. Per-Record Estimates ............................................................................................................................. 29 3.2. Aggregate -

Let Her Finish: Gender, Sexism, and Deliberative Participation in Australian Senate Estimates Hearings (2006-2015)

Let Her Finish: Gender, Sexism, and Deliberative Participation In Australian Senate Estimates Hearings (2006-2015) Joanna Richards School of Government and Policy Faculty of Business, Government and Law University of Canberra ABSTRACT In 2016, Australia ranks 54th in the world for representation of women in Parliament, with women accounting for only 29% of the House of Representatives, and 39% of the Senate. This inevitably inspires discussion about women in parliament, quotas, and leadership styles. Given the wealth of research which suggests that equal representation does not necessarily guarantee equal treatment, this study focuses on Authoritative representation. That is, the space in between winning a seat and making a difference where components of communication and interaction affect the authority of a speaker.This study combines a Discourse Analysis of the official Hansard transcripts from the Senate Estimates Committee hearings, selected over a 10 year period between 2006 and 2015, with a linguistic ethnography of the Australian Senate to complement results with context. Results show that although female senators and witnesses are certainly in the room, they do not have the same capacity as their male counterparts. Both the access and effectiveness of women in the Senate is limited; not only are they given proportionally less time to speak, but interruption, gate keeping tactics, and the designation of questions significantly different in nature to those directed at men all work to limit female participation in the political domain. As witnesses, empirical measures showed that female testimony was often undermined by senators. Results also showed that female senators and witnesses occasionally adopted masculine styles of communication in an attempt to increase effectiveness in the Senate. -

First Century Fox Inc and Sky Plc; European Intervention Notice

Rt Hon Karen Bradley Secretary of State for Digital Culture Media and Sport July 14 2017 Dear Secretary of State Twenty-First Century Fox Inc and Sky plc; European Intervention Notice The Campaign for Press and Broadcasting is responding to your request for new submissions on the test of commitment to broadcasting standards. We are pleased to submit this short supplement to the submission we provided for Ofcom in March. As requested, the information is up-to-date, but we are adding an appeal to you to reconsider Ofcom’s recommendation to accept the 21CF bid on this ground, which we find wholly unconvincing in the light of the evidence we submitted. SKY NEWS IN AUSTRALIA In a pre-echo of the current buyout bid in the UK, Sky News Australia, previously jointly- owned with other media owners, became wholly owned by the Murdochs on December 1 last year. When the CPBF made its submission on the Commitment to Broadcasting Standards EIN to Ofcom in March there were three months of operation by which to judge the direction of the channel, but now there are three months more. A number of commentaries have been published. The Murdoch entity that controls Sky Australia is News Corporation rather than 21FC but the service is clearly following the Fox formula about which the CPBF commented to Ofcom. Indeed it is taking the model of broadcasting high-octane right-wing political commentary in peak viewing times even further. While Fox News has three continuous hours of talk shows on weekday evenings, Sky News Australia has five. -

Time for Submissions to Inquiry Into Building Inclusive and Accessible Communities

Senate Community Affairs References Committee More time for submissions to inquiry into building inclusive and accessible communities The Senate Community Affairs References Committee is inquiring into the delivery of outcomes under the National DATE REFERRED Disability Strategy 2010-2020 to build inclusive and 29 December 2016 accessible communities. SUBMISSIONS CLOSE The inquiry will examine the planning, design, management 28 April 2017 and regulation of the built and natural environment, transport services and infrastructure, and communication and NEXT HEARING information systems, including barriers to progress or To be advised innovation in these areas. It will also look at the impact of restricted access for people with disability on inclusion and REPORTING DATE participation in all aspects of life. 13 September 2017 The date for submissions to the inquiry has been extended to COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP Friday 28 April 2017. Senator Rachel Siewert (Chair) "The additional time will ensure that groups and individuals Senator Jonathon Duniam can make a contribution to the inquiry" said committee chair, (Deputy Chair) Senator Sam Dastyari Senator Rachel Siewert. "The committee is very keen to hear Senator Louise Pratt directly from people with disability and their families and Senator Linda Reynolds carers, as well as representative organisations. We would also Senator Murray Watt welcome submissions from service providers and innovators Senator Carol Brown who have improved accessibility in their communities or online." CONTACT THE COMMITTEE Senate Standing Committees "The committee encourages people to visit the committee's on Community Affairs website to get some more information about the inquiry and PO Box 6100 how to make a submission. -

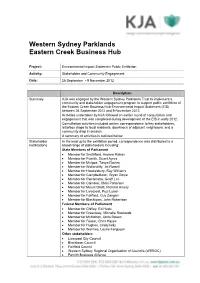

KJA Action Items Template

Western Sydney Parklands Eastern Creek Business Hub Project: Environmental Impact Statement Public Exhibition Activity: Stakeholder and Community Engagement Date: 26 September - 9 November 2012 Description Summary KJA was engaged by the Western Sydney Parklands Trust to implement a community and stakeholder engagement program to support public exhibition of the Eastern Creek Business Hub Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) between 26 September 2012 and 9 November 2012. Activities undertaken by KJA followed an earlier round of consultation and engagement that was completed during development of the EIS in early 2012. Consultation activities included written correspondence to key stakeholders, letterbox drops to local residents, doorknock of adjacent neighbours, and a community drop in session. A summary of activities is outlined below. Stakeholder In the lead up to the exhibition period, correspondence was distributed to a notifications broad range of stakeholders including: State Members of Parliament Member for Smithfield, Andrew Rohan Member for Penrith, Stuart Ayres Member for Mulgoa, Tanya Davies Member for Wollondilly, Jai Rowell Member for Hawkesbury, Ray Williams Member for Campbelltown, Bryan Doyle Member for Parramatta, Geoff Lee Member for Camden, Chris Patterson Member for Mount Druitt, Richard Amery Member for Liverpool, Paul Lynch Member for Fairfield, Guy Zangari Member for Blacktown, John Robertson Federal Members of Parliament Member for Chifley, Ed Husic Member for Greenway, Michelle Rowlands Member for -

Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific

How the fossil fuel industry, News Corp, and the Federal Government hijacked the Black Summer bushfires to prevent action on climate change Dirty Power: Burnt Country 1 Greenpeace Australia Pacific Greenpeace Australia Pacific Lead author Louis Brailsford Contributing authors Nikola Čašule Zachary Boren Tynan Hewes Edoardo Riario Sforza Design Olivia Louella Authorised by Kate Smolski, Greenpeace Australia Pacific, Sydney May 2020 www.greenpeace.org.au TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Introduction 6 2. The Black Summer bushfires 7 3. Deny, minimise, adapt: The response of the Morrison Government 9 Denial 9 Minimisation 10 Adaptation and resilience 11 4. Why disinformation benefits the fossil fuel industry 12 Business as usual 13 Protecting the coal industry 14 5. The influence of the fossil fuel lobby on government 16 6. Political donations and financial influence 19 7. News Corp’s disinformation campaign 21 News Corp and climate denialism 21 News Corp, the Federal Government and the fossil fuel industry 27 8. #ArsonEmergency: social media disinformation and the role of News Corp and the Federal Government 29 The facts 29 #ArsonEmergency 30 Explaining the persistence of #ArsonEmergency 33 Timeline: #ArsonEmergency, News Corp and the Federal Government 36 9. Case study – “He’s been brainwashed”: Attacking the experts 39 10. Case study – Matt Kean, the Liberal party minister who stepped out of line 41 11. Conclusions 44 End Notes 45 References 51 Dirty Power: Burnt Country 3 Greenpeace Australia Pacific EXECUTIVE SUMMARY stronger action to phase out fossil fuels, was aided by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp media empire, and a Australia’s 2019/20 Black coordinated campaign of social media disinformation. -

Political Career

About the Rev Hon Fred Nile MLC CONTENTS: • Family History • Brief Overview – Political Career • Academic Studies • Military Service • Full-Time Employment/ Elections to Parliament • Australian Speaking Tours • Overseas Speaking and Study Tours • Projects • Government Conferences and Inquiries • Legislation • Media • Affiliations and Memberships • Autobiography FAMILY HISTORY Rev. Fred Nile was born in Kings Cross, Sydney, in 1934. Fred's father, of Devon, UK, migrated to Australia after serving in the trenches of France during World War I. He worked as a taxi driver in Kings Cross. Fred's mother, Marjorie, migrated to Australia from New Zealand and was of Scottish heritage. She worked as a waitress in Kings Cross. Both of Fred's parents are now deceased, and are buried in Christchurch, New Zealand. Fred has one brother (deceased), Jim who lived in Sydney, and two sisters, Marjory and Mary, who live in Christchurch, New Zealand. Fred married Elaine in 1958. Together, they had four children: o Stephen: Retired NSW Senior Police Constable, Driving school instructor. o Sharon: Social Worker. o Mark: State School Teacher, Previously secondary (17 years) now primary o David: Retired NSW Senior Police Constable (injured on duty). Council Ranger Sadly, Elaine passed away on the 17th October, 2011 from Cancer of the liver after 3 years of Chemotherapy and operations. Fred was remarried in December 2013 to Silvana Nero. BRIEF OVERVIEW – POLITICAL CAREER o 1981 elected as Call to Australia Member to the NSW Legislative Council for 11 year term. o 1991 re-elected for an 8 year term. o 1999 re-elected as Christian Democratic Party Member for an 8 year term. -

Evobzq5zilluk8q2nary.Pdf

NOVEMBER 10 (GMT) – NOVEMBER 11 (AEST), 2020 YOUR DAILY TOP 12 STORIES FROM FRANK NEWS FULL STORIES START ON PAGE 3 NORTH AMERICA UK AUSTRALIA Trump blocks co-operation Optimism over vaccine rollout MP quits Labor frontbench The Trump administration threw the A coronavirus vaccine could start being Labor right faction warrior Joel Fitzgibbon presidential transition into tumult, distributed by Christmas after a jab has urged his party to make a major with President Donald Trump blocking developed by pharmaceutical giant shift on the environment and blue-collar government officials from co-operating Pfizer cleared a “significant hurdle”. voters after quitting shadow cabinet. with President-elect Joe Biden’s team Prime Minister Boris Johnson said initial Western Sydney MP Ed Husic replaced and Attorney General William Barr results suggested the vaccine was 90 per Fitzgibbon as the opposition’s resources authorizing the Justice Department to cent effective at protecting people from and agriculture spokesman after the probe unsubstantiated allegations of COVID-19 but warned these were “very, stunning resignation. Fitzgibbon has voter fraud. Some Republicans, including very early days”. been increasingly outspoken in a bruising Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, battle over energy policy with senior rallied behind Trump’s efforts to fight the figures from Labor’s left flank. election results. NORTH AMERICA UK NEW ZEALAND Election probes given OK Redundancies hit record high Napier braces for heavy rain Attorney General William Barr has More people were made redundant Flood-hit Napier residents remain on authorized federal prosecutors across between July and September than at any alert as more heavy rain is falling on the US to pursue “substantial allegations” point on record, according to new official the city, with another day of rain still to of voting irregularities, if they exist, before statistics, as the pandemic laid waste come. -

Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, Iview, Radio and Online

Media Release: 05.05.17 Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, iview, radio and online abc.net.au/news The 2017 Federal Budget will be handed down on Tuesday May 9 and the ABC has the best independent coverage on all platforms. We’ll have the first interview with Treasurer Scott Morrison, as well as in-depth analysis and expert commentary from the ABC’s leading political and business teams. What does Budget 2017 mean for you? Know the numbers, the politics, and the impact with ABC NEWS. Tuesday, 9 May – BUDGET DAY TELEVISION – ABC, the ABC NEWS channel & iview The Drum - 5.30pm on ABC & iview / 6.30pm AEST on the ABC NEWS channel As the press gallery bunkers down in the budget media lock-up, host John Barron and a panel of experts will count down to Budget 2017 and preview what to expect. ABC NEWS - 7pm on ABC & iview The news of the day and the lead up to the Federal Treasurer’s Budget speech. ABC NEWS BUDGET 2017 SPECIAL - on ABC, the ABC NEWS channel, iview, ABC NEWS online and simulcast live on the ABC News Facebook page. Leigh Sales hosts the ABC NEWS Budget 2017 special with Political Editor Chris Uhlmann live from Parliament House in Canberra. At 7:30pm AEST the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will deliver his second Federal Budget speech live from the House of Representatives. Just after 8pm, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will join Leigh Sales for his first interview of the night, followed by the response from the Opposition’s Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen. -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

Local Court of New South Wales Annual Review 2019

Local Court of New South Wales Annual Review 2019 Contents Foreword by Chief Magistrate of New South Wales 2 1. An overview of the Local Court 5 Jurisdictions and Divisions 6 The Magistrates 8 Chief Magistrate’s Executive Office 14 The work of the Local Court registries 15 2. Court operations during 2019 16 Criminal jurisdiction 17 Civil jurisdiction 20 Coronial jurisdiction 21 3. Diversionary programs and other aspects of the Court’s work 25 Diversionary programs 26 Technology in the Local Court 30 4. Judicial education and community involvement 32 Judicial education and professional development 33 Legal education in the community and participation in external bodies 36 Appendices 39 The Court’s time standards 40 The Court’s committees 41 2019 Court by Court statistics 42 1 Foreword by Chief Magistrate of New South Wales At the conclusion of the foreword to the 2018 The Local Court is no longer a relatively small Annual Review I expressed the view that ingredient of our justice system confined to dealing the Local Court had reached the limit of its with relatively minor matters. This is still part of its capacity to sustain its performance against its makeup however the Court is regularly engaged in Time Standards without an increase in judicial the finalisation of a steadily increasing category of resources. The year 2019 saw no increase more and more serious criminal offences. in the number of magistrates despite advice It is not uncommon for a magistrate to find from the Court to government that to maintain themselves dealing with dishonesty or money a sensible balance between expectations and laundering offences involving sums of money in outcomes, without unduly prejudicing the the hundreds of thousands of dollars.