07-07-99 Mac Maniaque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valeurs Actuelles

30 OCT/05 NOV 14 Hebdomadaire OJD : 94849 Surface approx. (cm²) : 328 N° de page : 69 1 RUE LULLI 75002 PARIS - 01 40 54 11 00 Page 1/1 Spectacles la question tout au long du spectacle On préfère l'original au succédané du Tristan-Bernard. D'autant plus que Pierre Palmade, qui assure la mise en scène, ne se démarque en rien de l'ori- ginal. Sans doute les acteurs ont-ils Théâtre trop vu le film : ils imitent leurs prédé- Pierre Palmade et sa bande reprennent "Le Père Noël cesseurs sans même s'en apercevoir. est une ordure" qui fut l'un des grands succès de la troupe Ainsi, quand Benoît Moret (Pierre) du Splendid à la fin des années 1970. Est-ce bien utile ? prononce le fameux « C'est cela, oui... », on croit entendre Thierry 1974 : Michel Blanc, Christian Cla- certains dîners le secret de fabrication Lhermitte. Le spectacle n'est pas hon- vier, Gérard Jugnot et Thierry Lher- des doubitchous de M. Preskovitch teux, non, mais quand on dispose si mitte, qui se sont liés au lycée Pasteur (« roulés à la main sous les aisselles ») facilement du film ou de la vidéo, de Neuilly-sur-Seine et ont suivi ensem- quand la maîtresse de maison vous pourquoi se contenter d'un ersatz ? » ble les cours de théâtre de Tsilla Chel- propose une part de gâteau montre Jacques Nerson ton (la future Tatie Danielle d'Etienne que vous êtes un puits d'érudition. Le Le Pêre Noël est une ordure, Chatiliez), ouvrent le café-théâtre du phénomène se reproduira plus tard dejosianeBalasko, Marie-Anne Chazel, Splendid. -

The Alien Tort Statute and the Law of Nations Anthony J

The University of Chicago Law Review Volume 78 Spring 2011 Number 2 @2011 by The University of Chicago ARTICLES The Alien Tort Statute and the Law of Nations Anthony J. Bellia Jrt & Bradford R. Clarktt Courts and scholars have struggled to identify the original meaning of the Alien Tort Statute (A TS). As enacted in 1789, the A TS provided "[that the district courts ... shall ... have cognizance ... of all causes where an alien sues for a tort only in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States." The statute was rarely invoked for almost two centuries. In the 1980s, lower federal courts began reading the statute expansively to allow foreign citizens to sue other foreign citizens for all violations of modern customary international law that occurred outside the United States. In 2004, the Supreme Court took a more restrictive approach. Seeking to implement the views of the First Congress, the Court determined that Congress wished to grant federal courts jurisdiction only over a narrow category of alien claims "correspondingto Blackstone's three primary [criminal] offenses [against the law of nations]: violation of safe conducts, infringement of the rights of ambassadors, and piracy." In this Article, we argue that neither the broaderapproach initially endorsed by t Professor of Law and Notre Dame Presidential Fellow, Notre Dame Law School. tt William Cranch Research Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School. We thank Amy Barrett, Tricia Bellia, Curt Bradley, Paolo Carozza, Burlette Carter, Anthony Colangelo, Michael Collins, Anthony D'Amato, Bill Dodge, Rick Garnett, Philip Hamburger, John Harrison, Duncan Hollis, Bill Kelley, Tom Lee, John Manning, Maeva Marcus, Mark McKenna, Henry Monaghan, David Moore, Julian Mortenson, Sean Murphy, John Nagle, Ralph Steinhardt, Paul Stephan, Ed Swaine, Jay Tidmarsh, Roger Trangsrud, Amanda Tyler, Carlos Vizquez, Julian Velasco, and Ingrid Wuerth for helpful comments. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

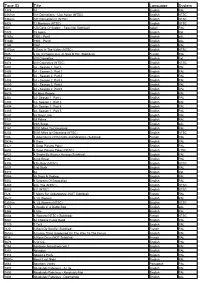

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Catalogue-2018 Web W Covers.Pdf

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE 22 years in Hollywood… The COLCOA French Film this year. The French NeWave 2.0 lineup on Saturday is Festival has become a reference for many and a composed of first films written and directed by women. landmark with a non-stop growing popularity year after The Focus on a Filmmaker day will be offered to writer, year. This longevity has several reasons: the continued director, actor Mélanie Laurent and one of our panels will support of its creator, the Franco-American Cultural address the role of women in the French film industry. Fund (a unique partnership between DGA, MPA, SACEM and WGA West); the faithfulness of our audience and The future is also about new talent highlighted at sponsors; the interest of professionals (American and the festival. A large number of filmmakers invited to French filmmakers, distributors, producers, agents, COLCOA this year are newcomers. The popular compe- journalists); our unique location – the Directors Guild of tition dedicated to short films is back with a record 23 America in Hollywood – and, of course, the involvement films selected, and first films represent a significant part of a dedicated team. of the cinema selection. As in 2017, you will also be able to discover the work of new talent through our Television, Now, because of the continuing digital (r)evolution in Digital Series and Virtual Reality selections. the film and television series industry, the life of a film or series depends on people who spread the word and The future is, ultimately, about a new generation of foreign create a buzz. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead Free Download

IN THE ELECTRIC MIST WITH CONFEDERATE DEAD FREE DOWNLOAD James Lee Burke | 416 pages | 22 Feb 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780752810652 | English | London, United Kingdom Review: In The Electric Mist With Confederate Dead While a good old fashion murder mystery awaits you, what is more important, as it is in the novels by James Lee Burke, is the story of Robicheaux. This hardcover is signed by James Lee Burke. Read more Murphy Doucet. A story from an alleged pimp corroborates a suspect, Murphy Doucet Bernard Hocke who, with his partner Twinkie Lemoyne Ned Beattyare responsible for the death of DeWitt Prejean, the skeleton found in the swamp. The defining moment of Burke's themes justice and heroism occurs at the end of the novel when Robicheaux sheds the constraints of his badge and takes matters into his own hands, going quite beyond the law, destroying the bad guys sure, but destroying them illegally. Namespaces Article Talk. I loved Will Patten's narration. The plot started out intriguing but quickly bogged down in a mishmash of interwoven stories—some of them supernatural but none of them terribly plausible—that the author picked up and dropped at random. Being a Civil War buff, I was intrigued with Robicheaux's encounters with Civil War General John Hood in the watery, bug and snake infested backwaters while searching for said remains of the black man. The best written Robicheaux so far, and that is a huge compliment in itself as the series is known for its silky prose. I liked it better than the book. -

Nationality, Statelessness and Migration in West Africa

Nationality, Migration and Statelessness in West Africa A study for UNHCR and IOM Bronwen Manby June 2015 UNHCR Regional Office for West Africa Route du Méridien Président Immeuble Faalo, Almadies Dakar, Senegal [email protected] Tel: +221 33 867 62 07 Fax: +221 33 867 62 15 International Organisation for Migration Regional Office for West and Central Africa Route des Almadies – Zone 3 Dakar, Senegal [email protected] Tel: +221 33 869 62 00 Fax: +221 33 869 62 33 @IOMROWCA / @IOM_News IOM Regional Office for West and Central Africa Web: www.rodakar.iom.int This report was prepared on the basis of field and other research during 2014. It was presented by the author at a Ministerial Conference on Statelessness in the ECOWAS region, held in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, 23 to 25 February 2015 and subsequently circulated to ECOWAS Member States and other stakeholders for comment. This final version integrates the comments made by states and others who were consulted for the report. The tables and other information in the report have been updated to the end of 2014. This report may be quoted, cited, uploaded to other websites and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of UNHCR or IOM. All names have been changed for the personal stories in boxes. Table of Contents List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................ i List of Boxes ........................................................................................................................................ -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

March 28-31, 2019

March 28-31, 2019 Most Beloved French Actor Thierry Lhermitte Leads Diverse Delegation of Filmmakers Eight Free Master Classes with actors, directors, authors, screenwriters, and cinematographers Exclusive Media Sponsor All films have English subtitles and are presented by their actors and directors. 27th annual • Byrd Theatre • Richmond, Va. • (804) 827-FILM • www.frenchfilmfestival.us Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond present Richmond,Virginia contents Film Schedule . p . 3 Lock in your pass for the Special Events . p . 4 28th French Film Festival Master Classes . pp . 7-15 with the 27th festival price 2019 Feature Films . pp . 16-32 Regular VIP Pass: $115 Libre . 16 Fait d’hiver . 17 Instructor VIP Pass: $105 Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge . 17 Student VIP Pass: $65 A Dry White Season . 18 Official Reception Add-On: $25 En mille morceaux . 19 Make check payable to: French Film Festival Le Procès contre Mandela et les autres . 20 Méprises . 22 Mark your calendars! Rémi sans famille . 23 28th French Film Festival Abdel et la Comtesse . 24 March 26-29, 2020 La Finale . 25 Tueurs . 26 Offer available only during weekend Le Collier rouge . 27 of Festival – see “Will Call Table” Tout ce qu’il me reste de la révolution . 28 Et mon coeur transparent . 29 Co-academic Sponsors Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Richmond present Les Chatouilles . 30 Richmond,Virginia March 22-25, 2018 March 30-April 2, 2017 L’Échange des princesses . 31 L’Ordre des médecins . 32 2019 Short Films . pp . 33-39 Saturday, March 30 Leur jeunesse . 33 All films have English subtitles Exclusive Media Sponsor Sans gravité . -

Safe Conduct? Twelve Years Fishing Under the UN Code

Safe Conduct? Twelve years fishing under the UN Code Tony J. Pitcher, Daniela Kalikoski, Ganapathiraju Pramod and Katherine Short December 2008 Table Of Contents Page Foreword .......................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................4 Introduction and Scope of the Analysis .....................................................................6 Methods .........................................................................................................................7 Results ............................................................................................................................8 Overall Compliance with the Code of Conduct ..........................................................8 Comparison among Questions .............................................................................10 Comparison of Intentions with Implementation of Code Compliance Measures . 10 Analysis of Issues Relating to Compliance with the Code of Conduct .................12 Reference points ..................................................................................................12 Irresponsible fishing methods; by-catch, discards and harmful fishing gear .......15 Ghost fishing ........................................................................................................18 Protected and no-take areas ...............................................................................19