Interdiscourse in the TV Serial Productions: a Demonstrative Exercise Matrizes, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Visio-HBO-#12742-V3

HBO LATIN AMERICA Proposed Take-Out and Restructuring with service flows (shows only top line subsidiaries) PRIVILEGED & CONFIDENTIAL ATTORNEY WORK PRODUCT. Draft 10/30/09A HOME BOX OFFICE, INC. 100% SONY Ole Communications HBO LATIN AMERICA HOLDINGS, L.L.C. SONY Ole Communications 80% 80% 10% 10% 10% 10% 5% EXISTING SUBSIDIARY ENTITIES (same rights as HBO Latin America): HBO Latin America Production Services, L.C. HBO LATIN AMERICA (Sunrise Regional Uplink Facility) (merger of HBO Ole Partners and HBO Brasil Partners; converts to Delaware LLC) HBO OLE PRODUCCIONES, C.A. (Venezuela) 5% PAN-REGIONAL PREMIUM BUSINESS (HBO & CINEMAX) DMS Media Services, L.L.C. **All voting by majority, except for customary TECHNICAL minority protective rights. SERVICES AGREEMENTS TECHNICAL SERVICES SALES AND FEES SALES AND MARKETING PROF. & ADMIN PROF. & ADMIN MARKETING REP SERVICES SERVICES FEE SERVICE FEE AGREEMENT 90%** AGREEMENT (COST PLUS) (COST PLUS) (Premium: HBO/MAX) SALES AND MARKETING REPRESENTATION AGREEMENTS (BASIC/AD SUPPORTED) CHANNEL DISTRIBUTION CO. SALES AND MARKETING SERVICE FEE SONY BASIC OLE BASIC TIME WARNER (Merger of HBO Ole Distribution, L.L.C. (COST PLUS) CHANNELS * CHANNELS* CHANNELS* and Brasil Distribution, L.L.C.) PROF. & ADMIN SERVICES AGREEMENT PREMIUM CHANNEL CHANNEL DISTRIBUTION BUSINESS LICENSE FEES PROF. & ADMIN SERVICES FEE (COST PLUS) ** All voting is unanimous, but HBO, Inc. (not HBO LA) exercises the voting shares of HBO Latin America. BASIC CHANNEL BUSINESSES BASIC LICENSE FEES BASIC LICENSE FEES BASIC LICENSE FEES As sales representative, Channel Distribution Co. sells Basic Channel services to third party platform operators, enters into distribution *Includes any channel business owned 50% or more, agreements with operators on behalf of Basic Channels, collects fee now or in the future. -

As Telenovelas Brasileiras: Heróis E Vilões

AS TELENOVELAS BRASILEIRAS: HERÓIS E VILÕES Maria Lourdes Motter Professora livre-docente da Escola de Comunicação e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, coordenadora do NPTN-ECA USP e do Núcleo de Pesquisa Ficção Seriada da Intercom. É autora dos livros Ficção e história: imprensa e construção da realidade e Ficção e realidade: a construção do cotidiano na telenovela. E-mail: [email protected] 64 ALAIC - 1-85 64 9/27/04, 5:34 PM RESUMO O presente trabalho tem por objetivo refletir sobre o modelo atual de telenovela brasileira, buscando identificar nas narrativas os deslocamentos que a afastam da qualidade crescente alcançada na última década. Categorias de personagens como herói e vilão são analisadas para avaliar o grau de protagonismo de cada um e identificar, nas telenovelas no ar no primeiro semestre de 2004, possível inclinação tendencial para a simplificação narrativa - com repetição de fórmulas, estratégias e esquemas maniqueístas - e recuperação de elementos do folhetim clássico. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: TELENOVELA • PERSONAGEM • HERÓI • VILÃO •BRASIL. ABSTRACT The current paper aims to ponder on the current model of Brazilian telenovelas, so as to detect in the narrative the causes for the downgrading in the quality that marked the past decade. Character categories such as heroes and villains are analyzed to assess their degree of protagonism and to spot in first-half 2004 telenovelas a possible tendency towards simplifying the narrative, by repeating formulae, strategies and manicheistic schemes, and recovering elements that belong to the classical folhetim (daily novel chapters formerly published in newspapers). KEY WORDS: TELENOVELA • CHARACTER • HERO • VILLAIN • BRAZIL. RESUMEN Este trabajo tiene por objetivo reflejar el modelo actual de la telenovela brasileña, buscando identificar en las narrativas las dislocaciones que la separan desde la creciente calidad 65 alcanzada en la última década. -

Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia

598 CONSTRUCTING IDENTITY Fictional Images of Real Places in Philadelphia A. GRAY READ University of Pennsylvania Fictional images ofreal places in novels and films shadow the city as a trickster, doubling its architecture in stories that make familiar places seem strange. In the opening sequence of Terry Gilliam's recent film, 12 Monkeys, the hero, Bruce Willis,rises fromunderground in the year 2027, toexplore the ruined city of Philadelphia, abandoned in late 1997, now occupied by large animals liberated from the zoo. The image is uncanny, particularly for those familiar with the city, encouraging a suspicion that perhaps Philadelphia is, after all, an occupied ruin. In an instant of recognition, the movie image becomes part of Philadelphia and the real City Hall becomes both more nostalgic and decrepit. Similarly, the real streets of New York become more threatening in the wake of a film like Martin Scorcese's Taxi driver and then more ironic and endearing in the flickering light ofWoody Allen's Manhattan. Physical experience in these cities is Fig. 1. Philadelphia's City Hall as a ruin in "12 Monkeys." dense with sensation and memories yet seized by references to maps, books, novels, television, photographs etc.' In Philadelphia, the breaking of class boundaries (always a Gilliam's image is false; Philadelphia is not abandoned, narrative opportunity) is dramatic to the point of parody. The yet the real city is seen again, through the story, as being more early twentieth century saw a distinct Philadelphia genre of or less ruined. Fiction is experimental life tangent to lived novels with a standard plot: a well-to-do heir falls in love with experience that scouts new territories for the imagination.' a vivacious working class woman and tries to bring her into Stories crystallize and extend impressions of the city into his world, often without success. -

Texto Completo

INTERCOM – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação XXVI Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – BH/MG – 2 a 6 Set 2003 A PRODUÇÃO DISCURSIVA DE PORTO DOS MILAGRES Diálogo com a realidade social e construção da identidade nacional Paula Guimarães Simões Mestranda / UFMG) Resumo: Este trabalho tem como objeto de estudo a telenovela Porto dos Milagres (Aguinaldo Silva e Ricardo Linhares, Rede Globo, 21h, 2001). A análise procura mostrar como, ao discutir as temáticas, a novela pode promover sentimentos de identificação entre sua narrativa e o público e, assim, como colabora na construção da identidade nacional. A telenovela é analisada como um cenário em que são produzidas várias representações sobre a sociedade brasileira. A pesquisa trabalhou com a narrativa completa de Porto dos Milagres, mas recortando alguns capítulos para a análise. Esta mostrou que as discussões empreendidas na ficção mantêm estreita relação com a realidade social e que essa novela apresenta um posicionamento crítico frente aos problemas enfrentados pela sociedade brasileira. Palavras-Chave: Telenovela, Identidade, Realidade Social. Introdução A telenovela ocupa um importante lugar na cultura nacional, discutindo temáticas e construindo representações sobre a sociedade brasileira. Gênero consolidado em nossa cultura, a telenovela é vista diariamente por milhões de brasileiros, conferindo visibilidade a temas, suscitando debates e atualizando valores presentes na realidade social. O discurso construído pela telenovela é lido, apreendido e re-significado pelas pessoas, que rediscutem suas temáticas e incorporam-nas à sua vida cotidiana. A telenovela está inserida na vida diária do público, ao mesmo tempo em que se apropria do cotidiano para compor as tramas, gerando um diálogo entre ficção e realidade. -

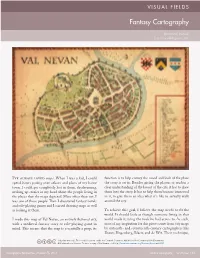

Fantasy Cartography

VISUAL FIELDS Fantasy Cartography Brian van Hunsel [email protected] I’ve always loved maps. When I was a kid, I could function is to help convey the mood and look of the place spend hours poring over atlases and plans of my home the story is set in. Besides giving the players or readers a town. I could get completely lost in them, daydreaming, clear understanding of the layout of the city, it has to draw making up stories in my head about the people living in them into the story. It has to help them become immersed the places that the maps depicted. More often than not, I in it, to give them an idea what it’s like to actually walk was one of those people. Then I discovered fantasy novels around the city. and role-playing games and I started drawing maps as well as looking at them. To achieve this goal, I believe the map needs to fit the world. It should look as though someone living in that I made this map of Val Nevan, an entirely fictional city, world made it, using the tools he had access to. As such, with a medieval fantasy story or role-playing game in most of my inspiration for this piece comes from city maps mind. This means that the map is essentially a prop; its by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cartographers like Braun, Hogenberg, Blaeu, and de Wit. Their technique, © by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. -

Between Static and Slime in Poltergeist

Page 3 The Fall of the House of Meaning: Between Static and Slime in Poltergeist Murray Leeder A good portion of the writing on Poltergeist (1982) has been devoted to trying to untangle the issues of its authorship. Though the film bears a directorial credit from Tobe Hooper, there has been a persistent claim that Steven Spielberg (credited as writer and producer) informally dismissed Hooper early in the process and directed the film himself. Dennis Giles says plainly, “Tobe Hooper is the director of record, but Poltergeist is clearly controlled by Steven Spielberg,” (1) though his only evidence is the motif of white light. The most concerted analysis of the film’s authorship has been by Warren Buckland, who does a staggeringly precise formal analysis of the film against two other Spielberg films and two other Hooper films, ultimately concluding that the official story bears out: Hooper directed the film, and Spielberg took over in postproduction. (2) Andrew M. Gordon, however, argues that Poltergeist deserves a place within Spielberg’s canon because so many of his trademarks are present, and because Spielberg himself has talked about it as a complementary piece for E .T.: The ExtraTerrestrial (1982). (3) A similar argument can be made on behalf of Hooper, however, with respect to certain narrative devices and even visual motifs like the perverse clown from The Funhouse (1981). Other scholars have envisioned the film as more of a contested space, caught between different authorial impulses. Tony Williams, for examples, speaks of Spielberg “oppressing any of the differences Tobe Hooper intended,” (4) which is pure speculation, though perhaps one could be forgiven to expect a different view of family life from the director of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) than that of E.T. -

Produ Awards 2020 - Lista De Finalistas

PRODU AWARDS 2020 - LISTA DE FINALISTAS RUBRO CATEGORÍA NOMINADO PAÍS GRUPO COMM. Contenidos Cápsulas El poder de los nombres (Mobius. Lab y Cisneros Group/Lifetime) México Ole Comm Contenidos Cápsulas Harina (ViacomCBS International Studios/YouTube) México ViacomCBS Contenidos Cápsulas La historia en números (Mobius Lab y Playmakers/History) México Ole Comm Contenidos Cápsulas Lifetime movies - Historias reales (Nippur Media/Lifetime) México Ole Comm Contenidos Cápsulas Un año en la historia (Mobius Lab y Playmakers/History) México Ole Comm Contenidos Miniserie Aquí en la tierra - segunda temporada (Buena Vista Original Productions y La Corriente del Golfo/Fox Premium & Fox App) México Disney Contenidos Miniserie El robo del siglo (Dynamo/Netflix) Colombia Netflix Contenidos Miniserie Hernán (Dopamine/Amazon, History, Azteca Siete) México Dopamine Contenidos Miniserie Los internacionales (Viacom CBS International Studio y The Mediapro Studio/Telefe/Flow) Argentina y Colombia ViacomCBS, Mediapro Contenidos Miniserie Tu parte del trato (Turner Latin America, Polka y Flow/TNT) Argentina WarnerMedia Contenidos Serie corta Broder (Planta Alta/TV Pública, Contar) Argentina TV Pública Contenidos Serie corta El método (RTVE y El Cañonazo Transmedia/RTVE) España RTVE Contenidos Serie corta Luimelia (Atresmedia/Atresplayer.com) España Atresmedia Contenidos Serie corta S.O.S. mamis!!! (Tiki Group y Elefantec Global/Instagram, Facebook, YouTube) Chile Tiki Group Contenidos Serie corta Terapia en cuarentena (Contar y Casa productora NOS/Contar) Argentina -

Telenovela Brasileira

almanaque_001a012.indd 1 28.08.07 11:34:50 almanaque_001a012.indd 2 28.08.07 11:34:51 Nilson Xavier ALMANAQUE DA TELENOVELA BRASILEIRA Consultoria Mauro Alencar almanaque_001a012.indd 3 28.08.07 11:34:55 Copyright © 2007 Nilson Xavier Supervisão editorial Marcelo Duarte Assistente editorial Tatiana Fulas Projeto gráfico e diagramação Nova Parceria Capa Ana Miadaira Preparação Telma Baeza G. Dias Revisão Cristiane Goulart Telma Baeza G. Dias CIP – Brasil. Catalogação na fonte Sindicato Nacional dos Editores de Livros, RJ Xavier, Nilson Almanaque da telenovela brasileira. Nilson Xavier. 1ª ed. – São Paulo : Panda Books, 2007. 1. Novelas de rádio e televisão. 2. Televisão – Programas I. Título. 07-1608 CDD 791.4550981 CDU 654.191(81) 2007 Todos os direitos reservados à Panda Books Um selo da Editora Original Ltda. Rua Lisboa, 502 – 05413-000 – São Paulo – SP Tel.: (11) 3088-8444 – Fax: (11) 3063-4998 [email protected] www.pandabooks.com.br almanaque_001a012.indd 4 28.08.07 11:34:55 À memória da professora Maria Lourdes Motter, por todo seu trabalho acadêmico na Universidade de São Paulo e dedicação em prol do estudo da telenovela brasileira. almanaque_001a012.indd 5 28.08.07 11:34:56 Agradecimentos Celso Fernandes, Danilo Rodrigues, Diego Erlacher, Edgar C. Jamarim, Edinaldo Cordeiro Jr., Eduardo Dias Gudião, Elmo Francfort, Fábio Costa, Fabio Machado, Flávio Michelazzo, Gesner Perion Avancini, Giseli Martins, Henrique Cirne Lima, Hugo Costa, Hugo Meneses, Ivan Gomes, João Costa, Leonardo Ferrão Brasil, Luís Marcio Arnaut de Toledo, Mabel Pereira, Magno Lopes, Marcelo Kundera, Paulo Marcos Dezoti, Raphael Machado, Robson Rogério Valder, Romualdo Emílio, Samuel Costa, Teopisto Abath, Watson H. -

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE a Jumpchain CYOA

MATTHEW REILLY UNIVERSE A Jumpchain CYOA Welcome to the shared universe of Matthew Reilly’s novels. You, visitor, are at the tip of the spear. This world of high stakes, nail-biting action needs heroes like you, now more than ever, to defend its people from forces that would seek to control it for their own ends. To explain a little more about the world you’ve stumbled into, to the vast bulk of humanity the world is quite mundane; your average citizen has as roughly the same concept of their world as you or I, and it would be quite easy to live your life as though nothing was any different. Yet behind the curtain, many wheels are in motion. Intelligence organisations and Special Forces units clash in exotic locations – Antarctic research labs, overgrown ruins, secret military facilities – often where highly unusual discoveries are made and where the most daring come away with the prize. Heavily-armed bounty hunters and Private Military Corporations chase lucrative contracts across the world for money and glory; careless of international law and often any collateral damage. In uncharted wilds, hidden cultures and tribes who have never been exposed to the modern world protect secrets from the forgotten past and carry out the rites of their forefathers to this day. Shadowy groups steer the courses of governments with hidden hands. Conspiracies of hate and enlightenment both grow inky webs throughout the military-industrial complex and permeate universities, corporations, the government and other institutions. And behind even these secret manipulators lie great mysteries which continue to shape the world as we know it after many thousands of years, and which may spell its doom...or its salvation.