White Noise and Newer Media: the Prophetic Impact of Jack's Avatars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack Johnson Versus Jim Crow Author(S): DEREK H

Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Author(s): DEREK H. ALDERMAN, JOSHUA INWOOD and JAMES A. TYNER Source: Southeastern Geographer , Vol. 58, No. 3 (Fall 2018), pp. 227-249 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26510077?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Southeastern Geographer This content downloaded from 152.33.50.165 on Fri, 17 Jul 2020 18:12:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Jack Johnson versus Jim Crow Race, Reputation, and the Politics of Black Villainy: The Fight of the Century DEREK H. ALDERMAN University of Tennessee JOSHUA INWOOD Pennsylvania State University JAMES A. TYNER Kent State University Foundational to Jim Crow era segregation and Fundacional a la segregación Jim Crow y a discrimination in the United States was a “ra- la discriminación en los EE.UU. -

The Polis Artist: Don Delillo's Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Political Science Faculty Research and Scholarship Political Science 2016 The oliP s Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Joel Alden Schlosser Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Custom Citation J. Schlosser, “The oP lis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and Politics of Literature.” Theory & Event 19.1 (2016). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/polisci_pubs/32 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1/30/2016 Project MUSE - Theory & Event - The Polis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Access provided by Bryn Mawr College [Change] Browse > Philosophy > Political Philosophy > Theory & Event > Volume 19, Issue 1, 2016 The Polis Artist: Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis and the Politics of Literature Joel Alden Schlosser (bio) Abstract Recent work on literature and political theory has focused on reading literature as a reflection of the damaged conditions of contemporary political life. Examining Don DeLillo’s Cosmopolis, this essay develops an alternative approach to the politics of literature that attends to the style and form of the novel. The form and style of Cosmopolis emphasize the novel’s own dissonance with the world it criticizes; they moreover suggest a politics of poetic worldmaking intent on eliciting collective agency over the commonness of language. -

Abstract Rereading Female Bodies in Little Snow-White

ABSTRACT REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISIBILITY By Dianne Graf In this thesis, the circumstances and events that motivate the Queen to murder Snow-White are reexamined. Instead of confirming the Queen as wicked, she becomes the protagonist. The Queen’s actions reveal her intent to protect her physical autonomy in a patriarchal controlled society, as well as attempting to prevent patriarchy from using Snow-White as their reproductive property. REREADING FEMALE BODIES IN LITTLE SNOW-WHITE: INDEPENDENCE AND AUTONOMY VERSUS SUBJUGATION AND INVISffiILITY by Dianne Graf A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 December 2008 INTERIM PROVOST AND VICE CHANCELLOR t:::;:;:::.'-H.~"""-"k.. Ad visor t 1.. - )' - i Date Approved Date Approved CCLs~ Member FORMAT APPROVAL 1~-05~ Date Approved ~~ I • ~&1L Member Date Approved _ ......1 .1::>.2,-·_5,",--' ...L.O.LJ?~__ Date Approved To Amanda Dianne Graf, my daughter. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Dr. Loren PQ Baybrook, Dr. Karl Boehler, Dr. Christine Roth, Dr. Alan Lareau, and Amelia Winslow Crane for your interest and support in my quest to explore and challenge the fairy tale world. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER I – BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE LITERARY FAIRY TALE AND THE TRADITIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE FEMALE CHARACTERS………………..………………………. 3 CHAPTER II – THE QUEEN STEP/MOTHER………………………………….. 19 CHAPTER III – THE OLD PEDDLER WOMAN…………..…………………… 34 CHAPTER IV – SNOW-WHITE…………………………………………….…… 41 CHAPTER V – THE QUEEN’S LAST DANCE…………………………....….... 60 CHAPTER VI – CONCLUSION……………………………………………..…… 67 WORKS CONSULTED………..…………………………….………………..…… 70 iv 1 INTRODUCTION In this thesis, the design, framing, and behaviors of female bodies in Little Snow- White, as recorded by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm will be analyzed. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Jack Kerouac's Poetics: Repetition, Language, and Narration in Letters from 1947 to 1956

Department of English Jack Kerouac’s Poetics: Repetition, Language, and Narration in Letters from 1947 to 1956 Nicholas Charles Baldwin Master’s Thesis Transnational Creative Writing Spring, 2019 Supervisor: Adnan Mahmutovic Baldwin 2 Abstract Despite the fame the prolific impressionistic, confessional poet, novelist, literary iconoclast, and pioneer of the Beat Generation, Jack Kerouac, has acquired since the late 1950’s, his written letters are not recognized as works of literature. The aim of this thesis is to examine the different ways in which Kerouac develops and employs the poetics he is most known for in the letters he wrote to friends, family, and publishers before becoming a well-known literary figure. In my analysis of Kerouac’s poetics, I analyze 20 letters from Selected Letters, 1940-1956. These letters were written before the publication of his best-known literary work, On The Road. The thesis attempts to highlight the characteristics of Kerouac’s literary control in his letters and to demonstrate how the examination of these poetics: repetition, language, and narration merits the letters’ treatment as works of artistic literature. Likewise, through the scrutiny of my first novella, “Trails” it then illustrates how the in-depth analysis of Kerouac’s letters improved my personal poetics, which resemble the poetics featured in the letters. Keywords: Poetics; Letter Writing; Impressionism; Confessional; Repetition; Language; Vertical and Circular-Narration; Jack Kerouac; 1947-1956 Baldwin 3 For My Parents From the late 1940’s until the middle 1950’s Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), relatively unknown to the public as an author, was writing novels, poems, and letters extensively. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

Postwar Media Manifestations and Don Delillo Joshua Adam Boldt Eastern Kentucky University

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2011 Postwar Media Manifestations and Don DeLillo Joshua Adam Boldt Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Boldt, Joshua Adam, "Postwar Media Manifestations and Don DeLillo" (2011). Online Theses and Dissertations. 09. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/09 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Postwar Media Manifestations and Don DeLillo By Joshua Boldt Master of Arts Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2011 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May, 2011 Copyright © Joshua Boldt 2011 All rights reserved ii Table of Contents Introduction: The Hyperreal, Hypercommodified American Identity 1 Chapter One: Postwar Advertising, Mass Consumption, and the 14 Construction of the Consumer Identity Chapter Two: News Media and American Complicity 34 Chapter Three: The Art of the Copy: Mechanical Reproductions and 50 Media Simulations Works Cited 68 iii Introduction: The Hyperreal, Hypercommodified American Identity This study examines the relationship between American media, advertising, and the construction of a postwar American identity. American media manifests itself in several different forms, all of which impact the consciousness of the American people, and the postwar rise to power of the advertising industry helped to mold identity in ways that are often not even recognized. -

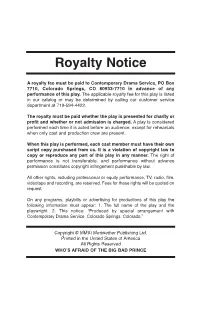

Royalty Notice

Royalty Notice A royalty fee must be paid to Contemporary Drama Service, PO Box 7710, Colorado Springs, CO 80933-7710 in advance of any performance of this play. The applicable royalty fee for this play is listed in our catalog or may be determined by calling our customer service department at 719-594-4422. The royalty must be paid whether the play is presented for charity or profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is considered performed each time it is acted before an audience, except for rehearsals when only cast and production crew are present. When this play is performed, each cast member must have their own script copy purchased from us. It is a violation of copyright law to copy or reproduce any part of this play in any manner. The right of performance is not transferable, and performance without advance permission constitutes copyright infringement punishable by law. All other rights, including professional or equity performance, TV, radio, film, videotape and recording, are reserved. Fees for these rights will be quoted on request. On any programs, playbills or advertising for productions of this play the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play and the playwright. 2. This notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Contemporary Drama Service, Colorado Springs, Colorado.” Copyright © MMXI Meriwether Publishing Ltd. Printed in the United States of America All Rights Reserved WHOS AFRAID OF THE BIG BAD PRINCE Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Prince A two-act fairy tale parody/mystery by Craig Sodaro Meriwether Publishing Ltd. -

'Little Terrors'

Don DeLillo’s Promiscuous Fictions: The Adulterous Triangle of Sex, Space, and Language Diana Marie Jenkins A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of English University of NSW, December 2005 This thesis is dedicated to the loving memory of a wonderful grandfather, and a beautiful niece. I wish they were here to see me finish what both saw me start. Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Chapter One 26 The Space of the Hotel/Motel Room Chapter Two 81 Described Space and Sexual Transgression Chapter Three 124 The Reciprocal Space of the Journey and the Image Chapter Four 171 The Space of the Secret Conclusion 232 Reference List 238 Abstract This thesis takes up J. G. Ballard’s contention, that ‘the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else,’ to show that Don DeLillo uses a particular sexual, cultural economy of adultery, understood in its many loaded cultural and literary contexts, as a model for semantic reproduction. I contend that DeLillo’s fiction evinces a promiscuous model of language that structurally reflects the myth of the adulterous triangle. The thesis makes a significant intervention into DeLillo scholarship by challenging Paul Maltby’s suggestion that DeLillo’s linguistic model is Romantic and pure. My analysis of the narrative operations of adultery in his work reveals the alternative promiscuous model. I discuss ten DeLillo novels and one play – Americana, Players, The Names, White Noise, Libra, Mao II, Underworld, the play Valparaiso, The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, and the pseudonymous Amazons – that feature adultery narratives. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

Indian Child Welfare Act: Keeping Our Children Connected to Our Community

FL OJJDP Hearing_Cover.ai 1 4/9/2014 5:08:34 PM AttorneyAttorney General’s Advisory Committee on American Indian/Alask a Nativeative Children Exposed to Violence Briefing Materials Hearing #3: April 16-17, 20142014 - Ft. Lauderdale, Florida Theme: American Indian Children Exposed to Violence in the Community Hyatt Regency Pier Sixty-Six Panorama Ballroom The Tribal Law and Policy Institute www.tlpi.org is providing technical assistance support for the Attorney General’s Task Force on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence including: (1) assisting the Task Force to conduct public hearings and listening sessions, (2) providing primary technical writing services for the final report, and (3) providing all necessary support for the Task Force and the public hearings. Table of Contents Agenda ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Day 1: Wednesday, April 16, 2014 ............................................................................................................ 1 Day 2: Thursday, April 17, 2014 ................................................................................................................ 7 Panel #1: Tribal Leader's Panel: Overview of Violence in Tribal Communities……………………………………..11 Potential Questions for Panelists ............................................................................................................ 15 Written Testimony for Brian Cladoosby ................................................................................................ -

Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2013 Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films Grace DuGar Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation DuGar, Grace, "Passive and Active Masculinities in Disney's Fairy Tale Films" (2013). ETD Archive. 387. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/387 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR Bachelor of Arts in Political Science Denison University May 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ENGLISH and the College of Graduate Studies by ____________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Rachel Carnell ______________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________________________ James Marino ______________________________ Department & Date ___________________________________________________________ Gary Dyer ______________________________ Department & Date PASSIVE AND ACTIVE MASCULINITIES IN DISNEY‘S FAIRY TALE FILMS GRACE DuGAR ABSTRACT Disney fairy tale films are not as patriarchal and empowering of men as they have long been assumed to be. Laura Mulvey‘s cinematic theory of the gaze and more recent revisions of her theory inform this analysis of the portrayal of males and females in Snow White, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and Aladdin.