Fossil Fuel Finance Report Card 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Annual Report 2020

2020 Annual Report Annual Report 2020 For further details about information disclosure, please visit the website of Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited at Important Notice The Board, Supervisory Committee and the Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant the authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the annual report and there are no misrepresentations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from the annual report for which they shall assume joint and several responsibilities. The 2020 Annual Report of Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited has been approved by the eleventh meeting of the eighth session of the Board. All ten Directors of quorum attended the meeting. SHINEWING (HK) CPA Limited issued the standard independent auditor report with clean opinion for the Company. Mr. Li Xiyong, Chairman of the Board, Mr. Zhao Qingchun, Chief Financial Officer, and Mr. Xu Jian, head of Finance Management Department, hereby warrant the authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the financial statements contained in this annual report. The Board of the Company proposed to distribute a cash dividend of RMB10.00 per ten shares (tax inclusive) for the year of 2020 based on the number of shares on the record date of the dividend and equity distribution. The forward-looking statements contained in this annual report regarding the Company’s future plans do not constitute any substantive commitment to investors and investors are reminded of the investment risks. There was no appropriation of funds of the Company by the Controlling Shareholder or its related parties for non-operational activities. There were no guarantees granted to external parties by the Company without complying with the prescribed decision-making procedures. -

The Mineral Industry of China in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook CHINA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of China By Sean Xun In China, unprecedented economic growth since the late of the country’s total nonagricultural employment. In 2016, 20th century had resulted in large increases in the country’s the total investment in fixed assets (excluding that by rural production of and demand for mineral commodities. These households; see reference at the end of the paragraph for a changes were dominating factors in the development of the detailed definition) was $8.78 trillion, of which $2.72 trillion global mineral industry during the past two decades. In more was invested in the manufacturing sector and $149 billion was recent years, owing to the country’s economic slowdown invested in the mining sector (National Bureau of Statistics of and to stricter environmental regulations in place by the China, 2017b, sec. 3–1, 3–3, 3–6, 4–5, 10–6). Government since late 2012, the mineral industry in China had In 2016, the foreign direct investment (FDI) actually used faced some challenges, such as underutilization of production in China was $126 billion, which was the same as in 2015. capacity, slow demand growth, and low profitability. To In 2016, about 0.08% of the FDI was directed to the mining address these challenges, the Government had implemented sector compared with 0.2% in 2015, and 27% was directed to policies of capacity control (to restrict the addition of new the manufacturing sector compared with 31% in 2015. -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

Collieries: Output Miners Scanned Their Faces Again to Pass Through a Security Gate

2 | Thursday, December 17, 2020 CHINA DAILY PAGE TWO Four years of progress made deep underground ZHAO RUIXUE Reporter’s log n a visit to a coal mine four years ago, I inter viewed a group of college graduates who decided to Obecome miners. They were working underground in grim conditions. In contrast, the mine I visited recently showcased the advantages brought by a range of smart tech nologies. In the middle of last month, I joined miners as they descended to a coalface at the Baodian Coal Mine in Shandong province, which is operated by the Shandong Energy Group. The miners’ faces were scanned as they opened lockers containing their work clothes, shoes, helmets, helmet lamps and selfrescue devices. They told me that a system pro viding realtime location monitor ing is built into their helmet lamps. Meng Zhan, who works at the Gaozhuang Mine in Jining, Shandong province, demonstrates how facilities at the coalface are used. ZHAO RUIXUE / CHINA DAILY Workers can be located from the control room by smart monitoring software, which provides vital data for search and rescue teams in the event of an emergency. After changing into work clothes and collecting their equipment, the Collieries: Output miners scanned their faces again to pass through a security gate. From that moment on, the names, location and number of miners at the coalface are displayed on a screen in the control room. If capacity increases the smart system finds that any of them have been drinking alcohol, they are denied entry. From page 1 The tragedy led to the wide leagues had to carry heavy picks After negotiating the security spread adoption of automated and dig coal from tunnel walls. -

Impacts and Mitigations of in Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands

Impacts and Mitigations of In Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands Neil Edmunds, P.Eng. V.P. Enhanced Oil Recovery Laricina Energy Ltd. Calgary, Alberta Submission to the XXIst World Energy Congress Montréal 2010 - 1 - Introduction: In Situ is the Future of Oil Sands The currently recognized recoverable resource in Alberta’s oil sands is 174 billion barrels, second largest in the world. Of this, about 150 billion bbls, or 85%, is too deep to mine and must be recovered by in situ methods, i.e. from drill holes. This estimate does not include any contributions from the Grosmont carbonate platform, or other reservoirs that are now at the early stages of development. Considering these additions, together with foreseeable technological advances, the ultimate resource potential is probably some 50% higher, perhaps 315 billion bbls. Commercial in situ bitumen recovery was made possible in the 1980's and '90s by the development in Alberta, of the Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) process. SAGD employs surface facilities very similar to steamflooding technology developed in California in the ’50’s and 60’s, but differs significantly in terms of the well count, geometry and reservoir flow. Conventional steamflooding employs vertical wells and is based on the idea of pushing the oil from one well to another. SAGD uses closely spaced pairs of horizontal wells, and effectively creates a melt cavity in the reservoir, from which mobilized bitumen can be collected at the bottom well. Figure 1. Schematic of a SAGD Well Pair (courtesy Cenovus) Economically and environmentally, SAGD is a major advance compared to California-style steam processes: it uses about 30% less steam (hence water and emissions) for the same oil recovery; it recovers more of the oil in place; and its surface impact is modest. -

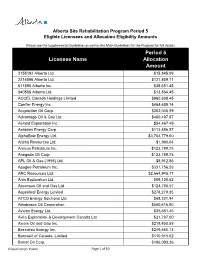

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount 2155192 Alberta Ltd. $15,845.09 2214896 Alberta Ltd. $121,809.11 611890 Alberta Inc. $35,651.45 840586 Alberta Ltd. $13,864.45 ACCEL Canada Holdings Limited $960,608.45 Conifer Energy Inc. $464,459.14 Acquisition Oil Corp. $302,046.99 Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd. $460,497.87 Aeneid Exploration Inc. $54,467.49 Aeraden Energy Corp. $113,886.57 AlphaBow Energy Ltd. $3,704,779.60 Altima Resources Ltd. $1,980.64 Amicus Petroleum Inc. $123,789.75 Anegada Oil Corp. $123,789.75 APL Oil & Gas (1998) Ltd. $8,912.86 Apogee Petroleum Inc. $331,756.53 ARC Resources Ltd. $2,664,945.71 Artis Exploration Ltd. $89,128.62 Ascensun Oil and Gas Ltd. $124,780.07 Aspenleaf Energy Limited $278,279.35 ATCO Energy Solutions Ltd. $68,331.94 Athabasca Oil Corporation $550,616.80 Avalon Energy Ltd. $35,651.45 Avila Exploration & Development Canada Ltd $21,787.00 Axiom Oil and Gas Inc. $219,850.59 Baccalieu Energy Inc. $249,560.13 Barnwell of Canada, Limited $110,915.62 Barrel Oil Corp. $196,083.36 #Classification: Public Page 1 of 10 Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount Battle River Energy Ltd. -

The Efficiency Evaluation of Energy Enterprise Group Finance

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 16 First International Conference on Economic and Business Management (FEBM 2016) The Efficiency Evaluation of Energy Enterprise Group Finance Companies Based on DEA Lina Jia a*, Ren Jin Sun a, Gang Lin b, LiLe Yang c a University of Petroleum, Beijing, China b China Construction Bank, Beijing (Branch), China c Xi'an Changqing Technology Engineering Co., Ltd., China *Corresponding author: Lina Jia, Master,E-mail:[email protected] Abstract: By the end of 2015, about 196 financial companies have been established in China. The energy finance companies accounted for about 25% of the proportion. Energy finance groups has some special character such as the big size of funds, the wide range of business, so the level of efficiency of its affiliated finance company has become the focus of attention. In this paper , we choose DEA to measure the efficiency(technical efficiency, pure technical efficiency, scale efficiency and return to scale ) and make projection analysis for fifty energy enterprise group finance companies in 2014. The following results were obtained:①The overall efficiency of the energy finance companies is not high. ①Under the condition of maintaining the current level of output, Most of the energy enterprise finance companies should be appropriate to reduce the input redundancy, so as to improve efficiency and avoid unnecessary waste. ③Some companies should continuously improve the internal management level to achieve the level and the size of output . Through the projection analysis, this paper provides some enlightenment and practical guidance for the improvement of the efficiency level of the non DEA effective energy group enterprise group. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 Annual Report MISSION Our mission is to facilitate innovation, collaborative research and technology development, demonstration and deployment for a responsible Canadian hydrocarbon energy industry. VISION Our vision is to help Canada become a global hydrocarbon energy technology leader. Contact Us For further information please contact: PTAC Petroleum Technology Alliance Canada Suite 400, Chevron Plaza, 500 Fifth Avenue SW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2P 3L5 MAIN: 403-218-7700 FAX: 403-920-0054 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.ptac.org PERSONNEL SOHEIL ASGARPOUR BRENDA BELLAND SUSIE DWYER LORIE FREI MARC GODIN President Manager, Knowledge Centre Innovation and Technology R&D Initiatives Assistant and Technical Advisor (403) 218-7701 (403) 218-7712 Development Web Site (403) 870-5402 [email protected] [email protected] Coordinator Administrator marc.godin@portfi re.com (403) 218-7708 (403) 218-7707 [email protected] [email protected] ARLENE MERLING TRUDY HIGH BOBBI SINGH LAURA SMITH TANNIS SUCH Director, Operations Administrative and Registration Accountant Controller Manager, Environmental (403) 218-7702 Coordinator (403) 218-7723 (403) 218-7701 Research [email protected] (403) 218-7711 [email protected] [email protected] Initiatives [email protected] (403) 218-7703 [email protected] PETROLEUM TECHNOLOGY ALLIANCE CANADA 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 3 Message from the Board A New Decade – A New Direction 2010 proved to be a turning point for PTAC as we redeined our role and PTAC Technology Areas set new strategies in motion. Over the past year PTAC has achieved goals in diverse areas of our organization: improving our inances, rebalancing our MANAGE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS project portfolios to address a broad spectrum of needs, leveraging support • Emission Reduction / Eco-eficiency for ield implementations, and building a measurably more effective and • Energy Eficiency eficient organization. -

Emerging Oil Sands Producers

RBC Dominion Securities Inc. Emerging Oil Sands Producers Mark Friesen (Analyst) (403) 299-2389 Initiating Coverage: The Oil Sands Manifesto [email protected] Sam Roach (Associate) Investment Summary & Thesis (403) 299-5045 We initiate coverage of six emerging oil sands focused companies. We are bullish with [email protected] respect to the oil sands sector and selectively within this peer group of new players. We see decades of growth in the oil sands sector, much of which is in the control of the emerging companies. Our target prices are based on Net Asset Value (NAV), which are based on a long-term flat oil price assumption of US$85.00/bbl WTI. The primary support for our December 13, 2010 valuations and our recommendations is our view of each management team’s ability to execute projects. This report is priced as of market close December 9, 2010 ET. We believe that emerging oil sands companies are an attractive investment opportunity in the near, medium and longer term, but investors must selectively choose the All values are in Canadian dollars companies with the best assets and greatest likelihood of project execution. unless otherwise noted. For Required Non-U.S. Analyst and Investment Highlights Conflicts Disclosures, please see • page 198. MEG Energy is our favourite stock, which we have rated as Outperform, Above Average Risk. We have also assigned an Outperform rating to Ivanhoe Energy (Speculative Risk). • We have rated Athabasca Oil Sands and Connacher Oil & Gas both as Sector Perform, (Above Average Risk). We have also assigned a Sector Perform rating to SilverBirch Energy (Speculative Risk). -

Notice of Applications Connacher Oil and Gas Limited Great Divide Expansion Project Athabasca Oil Sands Area

NOTICE OF APPLICATIONS CONNACHER OIL AND GAS LIMITED GREAT DIVIDE EXPANSION PROJECT ATHABASCA OIL SANDS AREA ENERGY RESOURCES CONSERVATION BOARD APPLICATION NO. 1650859 ALBERTA ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND ENHANCEMENT ACT APPLICATION NO. 003-240008 WATER ACT FILE NO. 00271543 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT The Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB/Board) has received Application No. 1650859 and Alberta Environment (AENV) has received Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (EPEA) Application No. 003-240008 and Water Act File No. 00271543 from Connacher Oil and Gas Limited (Connacher) for approval of the proposed Great Divide Expansion Project (the Project). This notice is to advise interested parties that the applications are available for viewing and that the ERCB, AENV, and other government departments are now undertaking a review of the applications and associated environmental impact assessment (EIA). Description of the Project Connacher has applied to construct, operate, and reclaim an in-situ oil sands project about 70 kilometres (km) south of the City of Fort McMurray in Townships 81, 82, and 83, Ranges 11 and 12, West of the 4th Meridian. Construction of the Project is proposed to begin in 2011, with increased production starting by 2012. The proposed Project would amalgamate Connacher’s existing Great Divide (EPEA Approval No. 223216-00-00) and Algar (EPEA Approval No. 240008-00-00) projects which were each designed to produce 1600 cubic metres per day (m3/day) (10 000 barrels per day [bbl/d]) of bitumen. The proposed Project would also increase Connacher’s bitumen production capacity to 7000 m3/day (44 000 bbl/d) at peak production using the in situ steam assisted gravity drainage (SADG) thermal recovery process. -

China's Expanding Overseas Coal Power Industry

Department of War Studies strategy paper 11 paper strategy China’s Expanding Overseas Coal Power Industry: New Strategic Opportunities, Commercial Risks, Climate Challenges and Geopolitical Implications Dr Frank Umbach & Dr Ka-ho Yu 2 China’s Expanding Overseas Coal Power Industry EUCERS Advisory Board Marco Arcelli Executive Vice President, Upstream Gas, Frederick Kempe President and CEO, Atlantic Council, Enel, Rome Washington, D.C., USA Professor Dr Hüseyin Bagci Department Chair of International Ilya Kochevrin Executive Director of Gazprom Export Ltd. Relations, Middle East Technical University Inonu Bulvari, Thierry de Montbrial Founder and President of the Institute Ankara Français des Relations Internationales (IFRI), Paris Andrew Bartlett Managing Director, Bartlett Energy Advisers Chris Mottershead Vice Principal, King’s College London Volker Beckers Chairman, Spenceram Limited Dr Pierre Noël Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah Senior Fellow for Professor Dr Marc Oliver Bettzüge Chair of Energy Economics, Economic and Energy Security, IISS Asia Department of Economics and Director of the Institute of Dr Ligia Noronha Director Resources, Regulation and Global Energy Economics (EWI), University of Cologne Security, TERI, New Delhi Professor Dr Iulian Chifu Advisor to the Romanian President Janusz Reiter Center for International Relations, Warsaw for Strategic Affairs, Security and Foreign Policy and President of the Center for Conflict Prevention and Early Professor Dr Karl Rose Senior Fellow Scenarios, World Warning, Bucharest Energy Council, Vienna/Londo Dr John Chipman Director International Institute for Professor Dr Burkhard Schwenker Chairman of the Strategic Studies (IISS), London Supervisory Board, Roland Berger Strategy Consultants GmbH, Hamburg Professor Dr Dieter Helm University of Oxford Professor Dr Karl Kaiser Director of the Program on Transatlantic Relations of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, USA Media Partners Impressum Design © 2016 EUCERS. -

Alberta Oil Sands Quarterly Update Fall 2013

ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE FALL 2013 Reporting on the period: June 18, 2013, to Sep. 17, 2013 2 ALBERTA OIL SANDS INDUSTRY QUARTERLY UPDATE Canada has the third-largest oil methods. Alberta will continue to rely reserves in the world, after Saudi to a greater extent on in situ production Arabia and Venezuela. Of Canada’s in the future, as 80 per cent of the 173 billion barrels of oil reserves, province’s proven bitumen reserves are 170 billion barrels are located in too deep underground to recover using All about Alberta, and about 168 billion barrels mining methods. are recoverable from bitumen. There are essentially two commercial This is a resource that has been methods of in situ (Latin for “in the oil sands developed for decades but is now place,” essentially meaning wells are gaining increased global attention Background of an used rather than trucks and shovels). as conventional supplies—so-called In cyclic steam stimulation (CSS), important global resource “easy” oil—continue to be depleted. high-pressure steam is injected into The figure of 168 billion barrels directional wells drilled from pads of bitumen represents what is for a period of time, then the steam considered economically recoverable is left to soak in the reservoir for a with today’s technology, but with period, melting the bitumen, and new technologies, this reserve then the same wells are switched estimate could be significantly into production mode, bringing the increased. In fact, total oil sands bitumen to the surface. reserves in place are estimated at 1.8 trillion barrels.