A Short Analysis of Joseph Hardy Neesima's Letters in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masonic Token

MASONIC TOKEN. WHEREBY ONE BROTHER MAY KNOW ANOTHER. VOLUME 3. PORTLAND, ME., OCT. 15, 1892. Ng. 22. Constitution. and Rev. Bro. J. L. Seward, of Waterville, Published quarterly by Stephen Berry, Jephtha Council of R. & S. Masters, No. delivered the oration. We return our No. 37 Plum Street, Portland, Maine. 17, at Farmington, was constituted Septem- thanks for an invitation. Twelve cts. per year in advance. ber 23d by Grand Master Wm. R. G. Estes, assisted by Deputy Grand Master Roak and The Grand Master has received tbe res Established March, 1867. 26th year. P. C. of Work Crowell, with companions ignation of R.W. Bro. Emilius W. Brown, filling the other offices. The officers were District Deputy Grand Master of the 2d Advertisements $4.00 per inch, or $3.00 for half an inch for one year. installed by Deputy Grand Master Roak, as Masonic District, and has appointed in his No advertisement received unless tlie advertiser, follows: Benjamin M. Hardy, tim; Seth E. place R. W. Albert Whipple Clark, of East- or some member of the firm, is a Freemason in dm pcw port. good standing. Beedy, ; S. Clifford Belcher, ; John ________________________ « J. Linscott, Rec. A Grand Chapter of the Order of the TO A MAINE POET. Dedication. Eastern Star was organized at Rockland, The new ball of Riverside Lodge, No. 135, August 24th. Miss Ella M. Day, of Rock- Kathleen Mavourneen !—The song is still ringing As fresh and as clear as the trill of the birds ; was dedicated September 14th by R. W. land, was elected Grand Worthy Matron ; In world-weary hearts it is sobbing and singing In pathos too sweet for the tenderest words. -

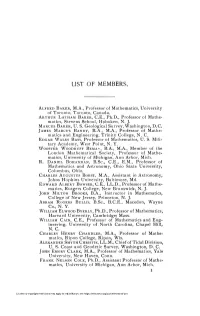

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

60459NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov.1 1 ------------------------ 51st Edition 1 ,.' Register . ' '-"978 1 of the U.S. 1 Department 1 of Justice 1 and the 1 Federal 1 Courts 1 1 1 1 1 ...... 1 1 1 1 ~~: .~ 1 1 1 1 1 ~'(.:,.:: ........=w,~; ." ..........~ ...... ~ ,.... ........w .. ~=,~~~~~~~;;;;;;::;:;::::~~~~ ........... ·... w.,... ....... ........ .:::" "'~':~:':::::"::'«::"~'"""">X"10_'.. \" 1 1 1 .... 1 .:.: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 .:~.:.:. .'.,------ Register ~JLst~ition of the U.S. JL978 Department of Justice and the Federal Courts NCJRS AUG 2 1979 ACQlJ1SfTIOI\fS Issued by the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 'U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1978 51st Edition For sale by the Superintendent 01 Documents, U.S, Government Printing Office WBShlngton, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 027-ootl-00631Hl Contents Par' Page 1. PRINCIPAL OFFICERFI OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 1 II. ADMINISTRATIV.1ll OFFICE Ul"ITED STATES COURTS; FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 19 III. THE FEDERAL JUDICIARY; UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS AND MARSHALS. • • • • • • • 23 IV. FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTIONS 107 V. ApPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • 113 Administrative Office of the United States Courts 21 Antitrust Division . 4 Associate Attorney General, Office of the 3 Attorney General, Office of the. 3 Bureau of Prisons . 17 Civil Division . 5 Civil Rights Division . 6 Community Relations Service 9 Courts of Appeals . 26 Court of Claims . '.' 33 Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 33 Criminal Division . 7 Customs Court. 33 Deputy Attorney General, Offico of. the 3 Distriot Courts, United States Attorneys and Marshals, by districts 34 Drug Enforcement Administration 10 Federal Bureau of Investigation 12 Federal Correctional Institutions 107 Federal Judicial Center • . -

New York Better Under Dry U

*. ' i V- M ■' '-.rv.;.- ■.-:■■•- y - u y ^ ' - y . ■'* ' .' ' •' ^ ' ■ THE WEATHER . Forecast by D. 8. Weather Butmu. NET PRESS RUN • - - Hartford. - -* AVERAGE DAILV OIROUIATION 'F air and slightiy colder tonight; for the Month of February, 1930 Saturday in cre^n g dondlness with slowly rldng temperatnre probably .< V*f^,-£j,« ■*® followed by rahu 5,503 rfsd-i 4 Ai.v»:is'•»■•-' Member* of the Anrtll Bureau ol ’• • j. **xf-x ’ ‘ ■ •• • .;/. •- ny>.. ■<■ • Circulation* _______ PRICE THREE CENTS SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, MARCH 14, 1930. EIGHTEEN PAGES (Classified Advertising on Page 16) VOL. X U V ., NO. 140. €- NEW YORK BETTER Southern France in Grip of Floods BLAINE MXES / X'*' ■■ V' V INTHTWITH UNDER DRY U W S G.O.P.IEADER u. s. I So Say Reports from Wefl Missionaries TeU Their E x-iFALL’S TESTIMONY Boston Wanted to Explain France To Build perien ces-A l Smilh Lost ’ ^ p y j RECORDS , Data of River Association t . Informed Quarters; if Ac Election Because of His | — and Senator Objects; May Its Own Guarantees cord Has Been Reach- ed It Is One of Outstand Wet Views. ' Prosecution at Doheny Trial Produce Records. Paris, March 14. (A.P)—French® The only hope expressed in official - -■ ^ circles was that some formula might ‘ --------- i official circles expressed toe feeling Reads Statements Made be found to prevent the London con ing Features of Confer Washington, March 14— (AP) Washington, March 14.— (AP.)— ; j.Qday that a guarantee of security ference ending in complete failure. "Little Old New York,” as they fre Claudius H<^ Huston, chairman o f. -

Matthew Thornton: Ancestors and Descendants

Matthew Thornton: Ancestors and Descendants by Whitney Durand July 25, 2010 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Descendants of Matthew Thornton Generation 1 1. Matthew Thornton-1[1] was born in 1714 in Derry, Kilskerry Parish (Tyrone) Northern Ireland[1]. He died on 24 Jun 1803 in Newburyport, Essex, Massachusetts[1]. Notes for Matthew Thornton: General Notes: Matthew Thornton was the son of James Thornton, a native of Ireland, and was born in that country, about the year 1714. When he was two or three years old, his father emigrated to America, and after a residence of a few years he removed to Worcester, Massachusetts. Here young Thornton received a respectable academical education, and subsequently pursued his medical studies, under the direction of Doctor Grout, of Leicester. Soon after completing his preparatory course, he removed to Londonderry, in New-Hampshire, where he commenced the practice of medicine, and soon became distinguished, both as a physician and a surgeon. In 1745, the well known expedition against Cape Breton was planned by Governor Shirley. The co-operation of New-Hampshire being solicited, a corps of five hundred men was raised in the latter province. Dr. Thornton was selected to accompany the New-Hampshire troops, as a surgeon. The chief command of this expedition was entrusted to colonel William Pepperell. On the 1st of May, he invested the city of Louisburg. Lieutenant Colonel Vaughan conducted the first column, through the woods, within sight of Louisburg, and saluted the city with three cheers. At the head of a detachment, chiefly of New-Hampshire troops, he marched in the night, to the northeast part of the harbour, where they burned the warehouses, containing the naval stores, and staved a large quantity of wine and brandy. -

Romanian Relations Partners Without a Partnership

140 Years of US – Romanian Relations Partners without a Partnership ALEXANDRU CRISTIAN Copyright © 2020 Alexandru Cristian All rights reserved. ISBN: CONTENTS FOREWORD – PARTNERS WITHOUT A 1 PARTNERSHIP 1 PRELIMINARIES OF THE US-ROMANIAN 4 RELATIONS 1.1 DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS PRIOR TO 10 INSTITUTIONALIZATION 2 MAKING THE US-ROMANIAN RELATIONS 14 OFFICIAL AND PERMANENT 2.1 EUGENE SCHUYLER, A DIPLOMAT 16 FRIEND TO ROMANIA 2.2 THE HELP PROVIDED BY THE 24 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR, AS WELL AS FOR ACCOMPLISHING THE GREAT UNIFICATION AS A CONCLUSION – LOOKING TOWARDS 27 THE FUTURE FOREWORD – PARTNERS WITHOUT A PARTNERSHIP Romania and the United States of America share some history which is similar in many respects. Both states have struggled to gain their independence, their sovereignty, and historical recognition. That in which they have followed a different path was pertaining to the civilization pattern in which each of the two states was established. We need to remind here, and pay all the due respect to them, the Romanian and American historians who have dealt with the early issues of the US-Romanian relations, that is Paul Cernovodeanu, Cornelia Bodea, Ion Stanciu, Dumitru Vitcu, Constantin Bușe, Keith Hitchins, Stephen Fischer- Galați, Radu R. Florescu, James F. Clarke, and many others. The US-Romanian relations celebrate 140 years of an extremely challenging existence, which has eventually proved both states’ admiration for the civilization pattern – Romania for acquiring its national 1 ALEXANDRU CRISTIAN independence and for implementing a genuine democratic model, whereas the United States of America for the cultural and linguistic miracle represented by the Romanian people. -

The Diamond of Psi Upsilon Mar 1941

3tt][i)[^^^ffl ^he gtj^^ of March. 1941 VOLUME XXVII NUMBER THREE ^^^^roi [I][0 [gDglg]SI i^^^a The Diamond of Psi Upsilon OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF PSI UPSILON FRATERNITY Published in November, January, March and June by THE diamond of PSI UPSILON, o Corporation not for pecuniary profit, organized under the laws of Illinois. Volume XXVII March, 1941 Number 3 AN OPEN FORUM FOR THE FREE DISCUSSION OF FRATERNITY MATTERS EDITOR John A. Cooper, Delta Delta '39 ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON THE DIAMOxXD Frederick S. Fales, Gamma '96, Chairman Warren C. Agry, Zeta '11 John C. Esty, Gamma '22 A. Northey Jones, Beta Beta '17 Oliver D. Keep, Delta Delta '25 William D. Kennedy, Delta Delta '16 J. J. E. Hessey, Nu '13 Scott Turner, Phi '02 LIFE SUBSCRIPTION FIFTEEN DOLLARS, ONE DOLLAR THE YEAR BY SUBSCRIPTION, SINGLE COPIES FIFTY CENTS Business and Editorial Offices Room 510, 420 Lexington Ave., New York City at Entered as Second Class Matter January 8, 19S6. at the Post Office Menasha, Wisconsin, under the Act of August H, 1912. Acceptance for mailing at special rate of postage provided for in Paragraph 4, Section 638, Act of February S8, 19S6, authorized January 8, 1936. DEAR DIAMOND The of this transaction was to sta Low piu-pose Scholarship bilize the finances and to insure that the Psi U Dear Diamond: house gets the same sort of protection when it is vacant during summer months, that other Unfortunately I have no ideas about how houses and at the same time, secure a to raise the scholarship of the undergraduate get, lower interest rate on the debt that lies on the chapter. -

Congressional Record-Senate. 1957

1910. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 1957 &tl<?Ill, Ohio, for the Johnson and Curtis bill, the Aikens bill, SENATE. the Hamilton-Owen bill, the MeCumber-Tkrell bill, the Dil lingham bill, the Burkett bill, the Johnson bill, all tor legisla WEDNESDAY, February 16, 1910. tion to incul<!ate moral reforms in the Nation---to the Cominit Prayer by the Chaplain, "Rev. Ulysses G. B. Pier<!e, D. D. tee on Alcoholic Liquor Tra.ffic. The Journal of yesterday's proceedings was read and approved. By Mr. LINDBERGH: Petition of citizens of Philbrook and Browerville, Minn.., against S. 404 and H. l. Res. 17, relative to INCOME TAX. Sunday <Observance in the District of Columbia-to the Com Mr. BROWN. I .hold in my hand a message to the legislature mittee on the District of Columbia. of New Jersey by the governor of that State on the subj-ect By Mr. LINDSAY; Pe1ition of Searle Manufacturing Com of the proposed .sixteenth amendment to the Constitution. I ask pany, of Troy, N~ Y., in favor Qf a r€.pea.l of the eorporation to have it printed in the REco:Jm -and printed as a document. tax clause in the Payne tariff bill-to the Committee on Ways (S. Doc. No. 365.) and Means. The VICE-PRESIDENT. Is there objection to the request .Also, petition of New York Typographical Union, No. 6, In of the Senator from Nebraska 1 The Chair hears none, and the ternational Typographical Union, against increase of postal order Is entered. rate on periodicals-to the Committee on the Post-Office and Th-e message follows : Post-Roads. -

A Finding Aid to the Downtown Gallery Records,1824-1974, Bulk 1926-1969, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Downtown Gallery Records,1824-1974, bulk 1926-1969, in the Archives of American Art Catherine Stover Gaines Funding for the processing, microfilming and digitization of the microfilm of this collection was provided by the Henry Luce Foundation. Glass plate negatives in this collection were digitized in 2019 with funding provided by the Smithsonian Women's Committee. 2000 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 8 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix B: Chronological List of Downtown Gallery Exhibitions................................. 10 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 25 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 28 -

Sixty-First Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of The

Australian 1.~~~~~1 I ~~i~~~p,~ r ~ -I SIXTY-FIRST ANNUAL REPORT of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at WVest Point, New York June 11, 1930 C)rinted by The Moore Printing Company, Inc. Newburgh, N: Y. CI cel r-- GONTENTS Photograph-Annual Meeting, 1930. Photograph Honorable Patrick J. Hurley, Secretary of War, Reviewing the Corps, Alumni Day, 1930. Foreword, by Brigadier General Avery D. Andrews, '86. Report of Annual Meeting. Annual Report of the Treasurer. Annual Report of the Secretary. Photograph-Review of the Corps by Alumni, June, 1930. Report of the Harmonic Division, Organ Committee. Photograph-Recognition. Officers of the Association. Board of Trustees of the Association. Photograph-Graduation Exercises, 1930. Board of Trustees of the Endowment Fund. Board of Trustees of the New Memorial Hall Fund. Photograph-The Long:gray Line, Alumni Day, 1930. Constitution and By-Laws. Photograph-Alumni Reviewing the Corps, June, 1930. Program for June Week. Photograph-Alumni Exercises, 1930. Program of Alumni Exercises. Photograph-An Airplane View of Michie Stadium and the New Polo Field. Our Finances, by Brigadier General Avery D. Andrews, '86. Photograph-Presentation of Diplomas by the Secretary of War, Hon. Patrick J. Hurley, June, 1930. Address of the Honorable Patrick J. Hurley, Secretary of War. Photograph-Architect's Drawing of New Cadet Barracks. Pictorial Plates of West Point. Miscellaneous Information. Photograph-The Corps. List of Class Representatives. Photograph-One Wing of Washington Hall, the New Cadet Mess. Visiting Alumni Officially Registered at West Point, June, 1930. Photograph-"Our Snowbound Highland Home." Graduates Who Have Died Since Last Annual Meeting. -

Descendants of Josiah Hardy

Descendants of Josiah Hardy by Whitney Durand August 7, 2011 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ancestors of Josiah Hardy Generation 1 1. Josiah Hardy. He died in Dec 1786. Notes for Josiah Hardy: General Notes: Came from Virginia in 1776 withn Nathaniel Hamilton and married Hamilton's daughter. Left Chatham on December 15, 1786 with three others with a fair wind and good weather for Boston. Found April 10, 1787 in Great Permit hollow, Truro, frozen, along with others in the party. Source: A Record of One Hundred Years of the Hardy Family, compiled by Josiah Hardy, 2d, Chatham, Mass, published in Boston in 1877 by Frank Wood, 352 Washington Street. The place of his birth or the names of his parents are not seen, but he married in Chatham, Mass., and he died at sea, having left Chatham for Boston, Dec. 15, 1786, and his frozen body being found the following April near Truro. (Family Record.) He served in the Revolution, and his name, called of Cape Cod, is given in a "List of prisoners exchanged at Rhode Island," dated Feb. 11, 1777, he being called a "Seaman." (Mass. Soldiers and Sailors in the Revolution, 7-267.) He is also given as a private in Capt. Nathaniel Free¬man's Co., Lieut. Col. Enoch Halletts Regt. (Barnstable County) enlisting Aug. 25, 1780. Discharged Oct. 13, 1780; service 1 mo. 23 days, the company being raised to reinforce the Con¬tinental Army for 3 months. (Ibid, 7-278.) Source: Holman, Albert L. Ancestry of Francis Alonzo Hardy. Chicago, 1923. -

Gnrztg Nf Amvriran Ammanhpry of 1112 Emma Nf Nlumhia

* d Charles Kendall A ams . Medical Inspector Howard Emerson Ames Naval Academy , Annapolis . Sm ith e Col George And rson Manila . Hon . Chas . Andrews Syracuse , N . Y . — . A . 2 . 0 0 . B rig Gen George L Andrews , U S , Ret . , 4 Columbia Road , Washington Hon . Charles Herbert Allen . N Francis Burke Allen , U S Hartford . Tu r em a n Capt Henry Allen , U . S . A Manila . e Luther All n Cleveland , Ohio . n 6 h t . 2 . 2 t S Col Joh Jacob Astor 3 W , New York * p Christo her Colon Augu r . Col . Dallas Bache . t . Commander Charles Johnson Badger Navy Dep , Washington 6 St . William Whitman Bailey , LL . D Cushing , Providence Stephen Baker . Ph . D . James Mark Baldwin , Princeton , N J 0 0 St . W . George Washington Ball 3 7 Q , N , Washington f . Pay Inspector R . T . M . Ball Navy Pay O fice , San Francisco ' k Ken tu c . Capt . W . J . Barnette . Comdg . y Brig . Gen . Thomas Francis Barr The B runswick , Back Bay , Boston . - t . Brig Gen . Thomas H . Barry Washing on . Paul Brandon Barringer , M . D Charlottesville , Va * William Malone Baskerville . * Richard Napoleon Batchelder . - . Ma en . j G Al fred Elliott Bates Metropolitan Club , Washington James Bowen Bayler Washington . Maj . John Henry Beacom , U . S . A American Embassy , London - W likesba r r e . A . L . t . Col Eugene Beauharnais Beaumont , U S , Ret , Pa B edlin er . Rev . Henry g Salem , M ass >' George E . Belknap . in . Ma e. Reginald Rowan Belknap , U . S . N U S S . Maj . John Bellinger Bellinger Washington m .