“We Must Learn Foreign Knowledge”: the Transpacific Education of a Samurai Sailor, 1864–1865

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masonic Token

MASONIC TOKEN. WHEREBY ONE BROTHER MAY KNOW ANOTHER. VOLUME 3. PORTLAND, ME., OCT. 15, 1892. Ng. 22. Constitution. and Rev. Bro. J. L. Seward, of Waterville, Published quarterly by Stephen Berry, Jephtha Council of R. & S. Masters, No. delivered the oration. We return our No. 37 Plum Street, Portland, Maine. 17, at Farmington, was constituted Septem- thanks for an invitation. Twelve cts. per year in advance. ber 23d by Grand Master Wm. R. G. Estes, assisted by Deputy Grand Master Roak and The Grand Master has received tbe res Established March, 1867. 26th year. P. C. of Work Crowell, with companions ignation of R.W. Bro. Emilius W. Brown, filling the other offices. The officers were District Deputy Grand Master of the 2d Advertisements $4.00 per inch, or $3.00 for half an inch for one year. installed by Deputy Grand Master Roak, as Masonic District, and has appointed in his No advertisement received unless tlie advertiser, follows: Benjamin M. Hardy, tim; Seth E. place R. W. Albert Whipple Clark, of East- or some member of the firm, is a Freemason in dm pcw port. good standing. Beedy, ; S. Clifford Belcher, ; John ________________________ « J. Linscott, Rec. A Grand Chapter of the Order of the TO A MAINE POET. Dedication. Eastern Star was organized at Rockland, The new ball of Riverside Lodge, No. 135, August 24th. Miss Ella M. Day, of Rock- Kathleen Mavourneen !—The song is still ringing As fresh and as clear as the trill of the birds ; was dedicated September 14th by R. W. land, was elected Grand Worthy Matron ; In world-weary hearts it is sobbing and singing In pathos too sweet for the tenderest words. -

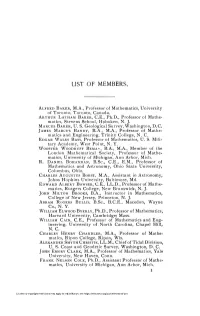

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Author TRC Environmental Corporation Prepared under BOEM Contract M08PD00024 by TRC Environmental Corporation 4155 Shackleford Road Suite 225 Norcross, Georgia 30093 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management New Orleans Gulf of Mexico OCS Region May 2012 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and TRC Environmental Corporation. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endoresements or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report is available only in compact disc format from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, at a charge of $15.00, by referencing OCS Study BOEM 2012-008. The report may be downloaded from the BOEM website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report also from the National Technical Information Service in the near future. Here are the addresses. You may also inspect copies at selected Federal Depository Libraries. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. -

60459NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov.1 1 ------------------------ 51st Edition 1 ,.' Register . ' '-"978 1 of the U.S. 1 Department 1 of Justice 1 and the 1 Federal 1 Courts 1 1 1 1 1 ...... 1 1 1 1 ~~: .~ 1 1 1 1 1 ~'(.:,.:: ........=w,~; ." ..........~ ...... ~ ,.... ........w .. ~=,~~~~~~~;;;;;;::;:;::::~~~~ ........... ·... w.,... ....... ........ .:::" "'~':~:':::::"::'«::"~'"""">X"10_'.. \" 1 1 1 .... 1 .:.: 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 .:~.:.:. .'.,------ Register ~JLst~ition of the U.S. JL978 Department of Justice and the Federal Courts NCJRS AUG 2 1979 ACQlJ1SfTIOI\fS Issued by the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 'U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1978 51st Edition For sale by the Superintendent 01 Documents, U.S, Government Printing Office WBShlngton, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 027-ootl-00631Hl Contents Par' Page 1. PRINCIPAL OFFICERFI OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE 1 II. ADMINISTRATIV.1ll OFFICE Ul"ITED STATES COURTS; FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 19 III. THE FEDERAL JUDICIARY; UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS AND MARSHALS. • • • • • • • 23 IV. FEDERAL CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTIONS 107 V. ApPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • 113 Administrative Office of the United States Courts 21 Antitrust Division . 4 Associate Attorney General, Office of the 3 Attorney General, Office of the. 3 Bureau of Prisons . 17 Civil Division . 5 Civil Rights Division . 6 Community Relations Service 9 Courts of Appeals . 26 Court of Claims . '.' 33 Court of Customs and Patent Appeals 33 Criminal Division . 7 Customs Court. 33 Deputy Attorney General, Offico of. the 3 Distriot Courts, United States Attorneys and Marshals, by districts 34 Drug Enforcement Administration 10 Federal Bureau of Investigation 12 Federal Correctional Institutions 107 Federal Judicial Center • . -

New York Better Under Dry U

*. ' i V- M ■' '-.rv.;.- ■.-:■■•- y - u y ^ ' - y . ■'* ' .' ' •' ^ ' ■ THE WEATHER . Forecast by D. 8. Weather Butmu. NET PRESS RUN • - - Hartford. - -* AVERAGE DAILV OIROUIATION 'F air and slightiy colder tonight; for the Month of February, 1930 Saturday in cre^n g dondlness with slowly rldng temperatnre probably .< V*f^,-£j,« ■*® followed by rahu 5,503 rfsd-i 4 Ai.v»:is'•»■•-' Member* of the Anrtll Bureau ol ’• • j. **xf-x ’ ‘ ■ •• • .;/. •- ny>.. ■<■ • Circulation* _______ PRICE THREE CENTS SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, MARCH 14, 1930. EIGHTEEN PAGES (Classified Advertising on Page 16) VOL. X U V ., NO. 140. €- NEW YORK BETTER Southern France in Grip of Floods BLAINE MXES / X'*' ■■ V' V INTHTWITH UNDER DRY U W S G.O.P.IEADER u. s. I So Say Reports from Wefl Missionaries TeU Their E x-iFALL’S TESTIMONY Boston Wanted to Explain France To Build perien ces-A l Smilh Lost ’ ^ p y j RECORDS , Data of River Association t . Informed Quarters; if Ac Election Because of His | — and Senator Objects; May Its Own Guarantees cord Has Been Reach- ed It Is One of Outstand Wet Views. ' Prosecution at Doheny Trial Produce Records. Paris, March 14. (A.P)—French® The only hope expressed in official - -■ ^ circles was that some formula might ‘ --------- i official circles expressed toe feeling Reads Statements Made be found to prevent the London con ing Features of Confer Washington, March 14— (AP) Washington, March 14.— (AP.)— ; j.Qday that a guarantee of security ference ending in complete failure. "Little Old New York,” as they fre Claudius H<^ Huston, chairman o f. -

Animal Painters of England from the Year 1650

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

Download 1 File

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

Matthew Thornton: Ancestors and Descendants

Matthew Thornton: Ancestors and Descendants by Whitney Durand July 25, 2010 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Descendants of Matthew Thornton Generation 1 1. Matthew Thornton-1[1] was born in 1714 in Derry, Kilskerry Parish (Tyrone) Northern Ireland[1]. He died on 24 Jun 1803 in Newburyport, Essex, Massachusetts[1]. Notes for Matthew Thornton: General Notes: Matthew Thornton was the son of James Thornton, a native of Ireland, and was born in that country, about the year 1714. When he was two or three years old, his father emigrated to America, and after a residence of a few years he removed to Worcester, Massachusetts. Here young Thornton received a respectable academical education, and subsequently pursued his medical studies, under the direction of Doctor Grout, of Leicester. Soon after completing his preparatory course, he removed to Londonderry, in New-Hampshire, where he commenced the practice of medicine, and soon became distinguished, both as a physician and a surgeon. In 1745, the well known expedition against Cape Breton was planned by Governor Shirley. The co-operation of New-Hampshire being solicited, a corps of five hundred men was raised in the latter province. Dr. Thornton was selected to accompany the New-Hampshire troops, as a surgeon. The chief command of this expedition was entrusted to colonel William Pepperell. On the 1st of May, he invested the city of Louisburg. Lieutenant Colonel Vaughan conducted the first column, through the woods, within sight of Louisburg, and saluted the city with three cheers. At the head of a detachment, chiefly of New-Hampshire troops, he marched in the night, to the northeast part of the harbour, where they burned the warehouses, containing the naval stores, and staved a large quantity of wine and brandy. -

Spurgeon Sermon Collection, Vol

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY SERMONS THE SPURGEON SERMON COLLECTION, VOL. 3 by Charles H. Spurgeon B o o k s F o r Th e A g e s AGES Software • Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1997 2 LOVE’S LOGIC SERMON NO. 1008 DELIVERED ON LORD’S-DAY MORNING, AUGUST 27TH, 1871, AT THE METROPOLITAN TABERNACLE, NEWINGTON “We love him because he first loved us.” — <620419>1 John 4:19. THIS is a great doctrinal truth, and I might with much propriety preach a doctrinal sermon from it, of which the sum and substance would be the sovereign grace of God. God’s love is evidently prior to ours: “He first loved us.” It is also clear enough from the text that God’s love is the cause of ours, for “We love him because he first loved us.” Therefore, going back to old time, or rather before all time, when we find God loving us with an everlasting love, we gather that the reason of his choice is not because we loved him, but because he willed to love us. His reasons, and he had reasons (for we read of the counsel of his will), are known to himself, but they are not to be found in any inherent goodness in us, or which was foreseen to be in us. We were chosen simply because he will have mercy on whom he will have mercy. He loved us because he would love us. The gift of his dear Son, which was a close consequent upon his choice of his people, was too great a sacrifice on God’s part to have been drawn from him by any goodness in the creature. -

The China Trade, 1830 to 1860

Early American Trade with China Early American Trade with China THE CHINA TRADE, 1830 TO 1860 In the years following the American Revolution, speed was the most important consider- ation for any ship even if it came at the expense of cargo space. Sailing ships tended to be small and swift so that they could outrun and outmaneuver British, French, or pirate vessels trying to capture them. By 1830, this threat had largely been eliminated, and a new type of clipper ship was developed. From 1841 through 1860, “extreme clippers” dominated the trade to Asia. These ships were large, carrying huge, lucrative cargoes of tea, spices, textiles, and chinaware to consumers in America and Europe. By the 1830s, trade routes were well estab- lished between the United States and China, and the names of ports in the Eastern hemi- sphere, once exotic and mysterious, were becoming increasingly familiar to Americans as places of importance to the United States’ economy. During the decades preceding and during the Civil War, the United States was largely focused on domestic matters and sectionalism rather than foreign policy. But it was also during this time that Americans, who had spent most of their history looking towards the East Coast and Europe, began to see the strategic and economic importance of developing the West Coast and maintaining shipping routes to the Far East. During the late 1850s, the United States’ trade with China declined. Domestic manufactures produced in factories in the rapidly industrializing northern states were replacing imports: cotton replaced nankeen, and American pottery factories replicated Chinese designs on porcelain, and coffee imported from central and South America was replacing Chinese tea. -

Description of the Largest Ship in the World, the New Clipper Great

DESCRIPTION OF TilE L .\ H 0 E ~ T ~ II I P I ~ T II E W 0 H L D. THE NEW CLIPPER GREAT REPUBLIC, OF DOSTOX. DESIGNED, BUILT AND OWNED :BY DONALD McKAY. The figures for this book are: Figure No. 1. Sail Plan Figure No. 2. Is a fore and aft vertical view of the ship amidships, showing side-views of the keel, mouldings of the floor timbers, depths of the midship keelsons, stanchions and their knees, beams, ledges and carlines, outlines of the decks and rail, stein, stern post and rudder, and positions of the masts and tanks. Figure No. 3. Is a view of the inside of the ship, representing the cross diagonal iron braces, the pointers, forward and aft, outlines of the decks and hanging knees, and the diagonals between the upper deck knees; also, the positions of the ports, the whole embraced in a general outline of her hull. Figure No. 4. Represents the horizontal outline of the third deck, with its beams and lodging knees, carlines, ledges and their knees, positions of the bitts, forward capstan, hatchways, masts and rudder case. Figure No. 5. Represents 10 outlines of her beamed hooks forward and aft, all numbered, with the style of their knees. Figure No. 6. Contains a plan of the mainmast, its hounds, trestle-trees, top, and two plans of its cap; also the topmast trestle-trees and cross-trees ; also, side and bed views of the forward capstan, showing the mode of heaving in the chain; also a representation of the midship section of the ship, which embraces the keel, outside planking, timbers, ceiling, keelsons, stanchions, the beams and their hanging knees, with the style of their bolting. -

NATIONAL REGISTER ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT VESSEL: SS Resolute

NATIONAL REGISTER ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT VESSEL: SS Resolute Left: Sistership SS Gopher State (ex-Export Leader) in 1986; Right: SS Resolute at the James River Reserve Fleet. Maritime Administration photos. Vessel History The SS Resolute is a moderately-sized, fully cellular, steam-propelled containership. It was built for Farrell Lines, Inc. of New York, by the Bath Iron Works (BIW) shipyard in Bath, Maine. Resolute was delivered February 22, 1980 and sailed on its maiden voyage February 26, 1980. It was the eighth and last in a series of virtually identical ships, the first of which, the Sea Witch, was completed by BIW for American Export-Isbrandtsen Lines in 1968. Beginning with the Sea Witch, the class was constructed in three groups; two of three ships each between 1968 and 1973, and two final ships that were completed in 1980. The eight ships were collectively known as the Sea Witch class and were built for the same operating company. However, in the 12 years between the completion of the Sea Witch and the Resolute, several corporate changes occurred. In 1960, the Isbrandtsen Steamship Company, headed by Jakob Isbrandtsen, acquired American Export Lines. The merged company, known as American Export-Isbrandtsen Lines, constructed the first three ships, and placed the orders for the second three. The first three ships, Sea Witch, Lightning, and Stag Hound followed Isbrandtsen’s practice of naming company ships after famous American clipper ships of the 19th Century. In the early 1970s Jakob Isbrandtsen experienced financial and legal difficulties, which forced him to relinquish his interest in the company.