Chapter 4. Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1977 A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) James Andrew Lackey Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, James Andrew, "A synopsis of Phaseoleae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) " (1977). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5832. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5832 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars

Food Structure Volume 11 Number 2 Article 9 1992 Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars Anup Engquist Barry G. Swanson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure Part of the Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Engquist, Anup and Swanson, Barry G. (1992) "Microstructural Differences Among Adzuki Bean (Vigna Angularis) Cultivars," Food Structure: Vol. 11 : No. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/foodmicrostructure/vol11/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Dairy Center at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Food Structure by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD STRUCTURE, Vol. II (1992), pp. 171-179 1046-705X/92$3.00+ .00 Scanning Microscopy International , Chicago (AMF O'Hare), IL 60666 USA MICROSTRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES AMONG ADZUKI BEAN (Vigna angularis) CULTIVARS An up Engquist and Barry G. Swanson Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6376 Abstract Introduction Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to Adzuki beans are one of the oldest cultivated beans study mi crostructural differences among five adzuki bean in the Orient, often used for human food, prepared as a cultivars: Erimo, Express, Hatsune, Takara and VBSC. bean paste used in soups and confections (Tjahjadi and Seed coat surfaces showed different patterns of cracks , Breene, 1984). The starch content of adzuki beans is pits and deposits . Cross-sections of the seed coats re about 50 %, while the protein content ranges between vealed well organized layers of elongated palisade cell s 20%-25% (Tjahjadi and Breene, 1984) . -

1 Assessment of Runner Bean (Phaseolus Coccineus L.) Germplasm for Tolerance To

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC 1 Assessment of runner bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) germplasm for tolerance to 2 low temperature during early seedling growth 3 4 A. Paula Rodiño1,*, Margarita Lema1, Marlene Pérez-Barbeito1, Marta Santalla1, & 5 Antonio M. De Ron1 6 1 Plant Genetic Resources Department, Misión Biológica de Galicia - CSIC, P. O. Box 7 28, 36080 Pontevedra, Spain (*author for correspondence, e-mail: 8 [email protected]) 9 1 1 Key words: Cold tolerance, characterization, diversity, genetic improvement 2 3 Summary 4 The runner bean requires moderately high temperatures for optimum germination and 5 growth. Low temperature at sowing delays both germination and plant emergence, and 6 can reduce establishment of beans planted early in the growing season. The objective of 7 this work was to identify potential runner bean germplasm with tolerance to low 8 temperature and to assess the role of this germplasm for production and breeding. Seeds 9 of 33 runner bean accessions were germinated in a climate-controlled chamber at 10 optimal (17 ºC-day/15 ºC-night) and at sub-optimal (14 ºC-day/8 ºC-night) temperature. 11 The low temperature tolerance was evaluated on the basis of germination, earliness, 12 ability to grow and vigor. Differences in agronomical characters were significant at low 13 temperatures for germination, earliness, ability to grow and early vigor except for 14 emergence score. The commercial cultivars Painted Lady Bi-color, Scarlet Emperor, the 15 Rwanda cultivar NI-15c, and the Spanish cultivars PHA-0013, PHA-0133, PHA-0311, 16 PHA-0664, and PHA-1025 exhibited the best performance under cold conditions. -

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans Session 2 Assessment Background Information Tips Goals Vegetables, Fruit, Assessment of Whole Grains, Current Eating Habits and Beans On an average DAY, how many servings of these Could be Needs to foods do you eat or drink? Desirable improved be improved 1. Greens and non-starchy vegetables like collard, 4+ 2-3 0-1 mustard, or turnip greens, salads made with dark- green leafy lettuces, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, carrots, okra, zucchini, squash, turnips, onions, cabbage, spinach, mushrooms, bell peppers, or tomatoes (including tomato sauce) 2. Fresh, canned (in own juice or light syrup), or 3+ 1-2 0 frozen fruit or 100% fruit juice (½ cup of juice equals a serving) 3a. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Never Some Most of with white flour of the time the time 3b. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Most Some Never with whole wheat flour of the time of the time In an average WEEK, how many servings of these foods do you eat? 4. Starchy vegetables like acorn squash, butternut 4-7 2-3 0-1 squash, beets, green peas, sweet potatoes, or yams (do not include white potatoes) 5. White potatoes, including French fries and 1 or less 2-3 4+ potato chips 6. Beans or peas like pinto beans, kidney beans, 3+ 1-2 0 black beans, lentils, butter or lima beans, or black-eyed peas Continued on next page Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, and Beans 19 Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, Assessment of and Beans Current Eating Habits In an average WEEK, how often or how many servings of these foods do you eat? 7a. -

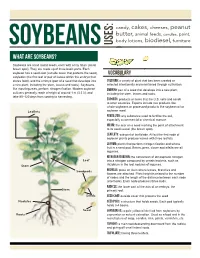

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Seed Mineral Composition and Protein Content of Faba Beans (Vicia Faba L.) with Contrasting Tannin Contents

agronomy Article Seed Mineral Composition and Protein Content of Faba Beans (Vicia faba L.) with Contrasting Tannin Contents Hamid Khazaei * and Albert Vandenberg Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A8, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-306-966-5859 Received: 17 March 2020; Accepted: 28 March 2020; Published: 3 April 2020 Abstract: Two-thirds of the world’s population are at risk of deficiency in one or more essential mineral elements. The high concentrations of essential mineral elements in pulse seeds are fundamentally important to human and animal nutrition. In this study, seeds of 25 genotypes of faba bean (12 low-tannin and 13 normal-tannin genotypes) were evaluated for mineral nutrients and protein content in three locations in Western Canada during 2016–2017. Seed mineral concentrations were examined by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and the protein content was determined by Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. Location and year (site-year) effects were significant for all studied minerals, with less effect for calcium (Ca) and protein content. Genotype by environment interactions were found to be small for magnesium (Mg), cobalt (Co), Ca, zinc (Zn), and protein content. Higher seed concentrations of Ca, manganese (Mn), Mg, and cadmium (Cd) were observed for low-tannin genotypes compared to tannin-containing genotypes. The protein content was 1.9% higher in low-tannin compared to tannin-containing genotypes. The high estimated heritability for concentrations of seed Mg, Ca, Mn, potassium (K), sulphur (S), and protein content in this species suggests that genetic improvement is possible for mineral elements. -

Benekecj.Pdf

THE EXPRESSION AND INHERITANCE OF RESISTANCE TO ACANTHOSCELIDES OBTECTUS (BRUCHIDAE) IN SOUTH AFRICAN DRY BEAN CULTIVARS by CASPER JOHANNES BENEKE Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the M.Sc. Agric. degree in the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences Department of Plant Sciences: Plant Breeding at the University of the Free State. May 2010 Supervisor: Prof. M.T. Labuschagne Co-supervisors: Prof. S.V.D.M. Louw & Dr. J.A. Jarvie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to PANNAR and STARKE AYRES for funding and allowing me the time to complete this thesis. I would like to thank all my colleagues at the Delmas and Kaalfontein research stations for all your moral support and patience with me over the duration of my studies. Dr. Antony Jarvie (Soybean and Drybean Breeder at PANNAR), a special thank you for providing plant material used in this study, all your guidance and for believing in my abilities. To my supervisors Professors Maryke Labuschagne, Schalk V.D.M. Louw and Dr. Antony Jarvie thank you very much for your support, guidance, assistance and patience with me, in making this thesis a great success. Many thanks to Mrs. Sadie Geldenhuys for all your administrative assistance and printing work done. Finally I give my sincere gratitude to my very supportive family, father, mother, sister and brother. Thank you very much for your support and understanding. To my wife Adri and daughter Shirly, you sacrificed so much for me. It was your sacrifice and support that have brought me this far. I thank God for having you all in my life. -

C10 Beano2.Gen-Wis

LEGUMINOSAE PART DEUX Papilionoideae, Genista to Wisteria Revised May the 4th 2015 BEAN FAMILY 2 Pediomelum PAPILIONACEAE cont. Genista Petalostemum Glycine Pisum Glycyrrhiza Psoralea Hylodesmum Psoralidium Lathyrus Robinia Lespedeza Securigera Lotus Strophostyles Lupinus Tephrosia Medicago Thermopsis Melilotus Trifolium Onobrychis Vicia Orbexilum Wisteria Oxytropis Copyrighted Draft GENISTA Linnaeus DYER’S GREENWEED Fabaceae Genista Genis'ta (jen-IS-ta or gen-IS-ta) from a Latin name, the Plantagenet kings & queens of England took their name, planta genesta, from story of William the Conqueror, as setting sail for England, plucked a plant holding tenaciously to a rock on the shore, stuck it in his helmet as symbol to hold fast in risky undertaking; from Latin genista (genesta) -ae f, the plant broom. Alternately from Celtic gen, or French genet, a small shrub (w73). A genus of 80-90 spp of small trees, shrubs, & herbs native of Eurasia. Genista tinctoria Linnaeus 1753 DYER’S GREENWEED, aka DYER’S BROOM, WOADWAXEN, WOODWAXEN, (tinctorius -a -um tinctor'ius (tink-TORE-ee-us or tink-TO-ree-us) New Latin, of or pertaining to dyes or able to dye, used in dyes or in dyeing, from Latin tingo, tingere, tinxi, tinctus, to wet, to soak in color; to dye, & -orius, capability, functionality, or resulting action, as in tincture; alternately Latin tinctōrius used by Pliny, from tinctōrem, dyer; at times, referring to a plant that exudes some kind of stain when broken.) An escaped shrub introduced from Europe. Shrubby, from long, woody roots. The whole plant dyes yellow, & when mixed with Woad, green. Blooms August. Now, where did I put that woad? Sow at 18-22ºC (64-71ºF) for 2-4 wks, move to -4 to +4ºC (34-39ºF) for 4-6 wks, move to 5-12ºC (41- 53ºF) for germination (tchn). -

Effect Supplementation of Mung Bean Sprouts

UASC Life Sciences 2016 The UGM Annual Scientific Conference Life Sciences 2016 Volume 2019 Conference Paper Effect Supplementation of Mung Bean Sprouts (Phaseolus radiatus L.) and Vitamin E in Rats Fed High Fat Diet Novidiyanto1, Muhammad Asrullah2, Lily Arsanti Lestari3, Siti Helmyati3, and Arta Farmawati4 1Department of Nutrition, Polytechnic of Health Pangkalpinang, Jl. Bukit Intan, Pangkalpinang, 33148, Indonesia 2School of Public Health Graduate Programme, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jl. Farmako Sekip Utara, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia 3Department of Health Nutrition, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Farmako Sekip Utara, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia 4Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Farmako Sekip Utara, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia Abstract The high fat diet consumed in daily will increase total cholesterol and oxidative stress Corresponding Author: levels, a risk factor of cardiovascular disease. Mung bean sprouts as a functional food Novidiyanto and vitamin E is an antioxidant component which acts to inhibit lipid peroxidation [email protected] process. The objective of this study is to determine the effect of supplementation of Received: 10 November 2018 mung bean sprouts and vitamin E on total cholesterol and MDA plasma level in rats Accepted: 6 January 2019 fed high-fat diet. Male rats Sprague Dawley (n = 24) were randomly divided into four Published: 10 March 2019 groups (6 in each group). The groups were fed on a normal diet (Group I), high fat diet (HFD) (Group II), HFD supplemented with 1 mL ⋅ g BW−1mung bean sprout (Group III), Publishing services provided by and HFD supplemented with 23 IU Vitamin E (Group IV). After 28 d, total cholesterol Knowledge E and MDA plasma level study were performed. -

Phaseolus Vulgaris (Beans)

1 Phaseolus vulgaris (Beans) Phaseolus vulgaris (Beans) dry beans are Brazil, Mexico, China, and the USA. Annual production of green beans is around 4.5 P Gepts million tonnes, with the largest production around Copyright ß 2001 Academic Press the Mediterranean and in the USA. doi: 10.1006/rwgn.2001.1749 Common bean was used to derive important prin- ciples in genetics. Mendel used beans to confirm his Gepts, P results derived in peas. Johannsen used beans to illus- Department of Agronomy and Range Science, University trate the quantitative nature of the inheritance of cer- of California, Davis, CA 95616-8515, USA tain traits such as seed weight. Sax established the basic methodology to identify quantitative trait loci (for seed weight) via co-segregation with Mendelian mar- Beans usually refers to food legumes of the genus kers (seed color and color pattern). The cultivars of Phaseolus, family Leguminosae, subfamily Papilio- common bean stem from at least two different domes- noideae, tribe Phaseoleae, subtribe Phaseolinae. The tications, in the southern Andes and Mesoamerica. In genus Phaseolus contains some 50 wild-growing spe- turn, their respective wild progenitors in these two cies distributed only in the Americas (Asian Phaseolus regions have a common ancestor in Ecuador and have been reclassified as Vigna). These species repre- northern Peru. This knowledge of the evolution of sent a wide range of life histories (annual to perennial), common bean, combined with recent advances in the growth habits (bush to climbing), reproductive sys- study of the phylogeny of the genus, constitute one of tems, and adaptations (from cool to warm and dry the main current attractions of beans as genetic organ- to wet). -

Lima Bean (Phaseolus Lunatus L.) – a Health Perspective

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 02, FEBRUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Lima Bean (Phaseolus Lunatus L.) – A Health Perspective Lourembam Chanu Bonita, G. A. Shantibala Devi and Ch. Brajakishor Singh Abstract: Lima beans are underutilized crops with a good nutritional profile. They are very good sources of proteins, minerals, dietary fibres and the essential amino acid lysine which is lacking in cereals. They are also good sources of bioactive compounds. Some of these compounds can adversely affect the health of the consumers, and are known as antinutritional compounds. Compounds like phytates, saponins, and phenols reduce the bioavailability of minerals. Cyanogenic glycosides which can be hydrolyzed into the highly toxic hydrogen cyanide are also known to be present in lima beans. Its content is highly variable among the different varieties. Another reason which makes lima beans unpopular to consumers is the presence of flatulence causing oligosaccharides. Different methods have been proposed to remove the content of these undesirable components. For most of them, soaking and cooking are enough to reduce their content to a desirable level. Bioactive compounds, including those which have been traditionally designated as antinutritional factors, can also affect the health in a beneficial way. Many compounds present in lima beans such as phenolic compounds are known to be antioxidants. The health promoting effects of lima beans and its constituents reported in literature so far include hypoglycemic, anti-HIV, anticancer, antihypertensive, bile acid binding, gastroprotective, protection from cardiovascular diseases and antimicrobial properties. These nutraceutical properties of lima beans are discussed in this review. Index Terms: Lima bean, nutritional, antinutritional, health, bioactive, anti-HIV, anticancer —————————— —————————— 1. -

![Structure and Enzyme Properties of Zabrotes Subfasciatus [Agr]-Amylase](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0060/structure-and-enzyme-properties-of-zabrotes-subfasciatus-agr-amylase-310060.webp)

Structure and Enzyme Properties of Zabrotes Subfasciatus [Agr]-Amylase

Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology 61:7786 (2006) Structure and Enzyme Properties of Zabrotes subfasciatus a-Amylase Patrícia B. Pelegrini,1 André M. Murad,1 Maria F. Grossi-de-Sá,2 Luciane V. Mello,2 Luiz A.S. Romeiro,3 Eliane F. Noronha,1 Ruy A. Caldas,1 and Octávio L. Franco1* Digestive a-amylases play an essential role in insect carbohydrate metabolism. These enzymes belong to an endo-type group. They catalyse starch hydrolysis, and are involved in energy production. Larvae of Zabrotes subfasciatus, the Mexican bean weevil, are able to infest stored common beans Phaseolus vulgaris, causing severe crop losses in Latin America and Africa. Their a-amylase (ZSA) is a well-studied but not completely understood enzyme, having specific characteristics when compared to other insect a-amylases. This report provides more knowledge about its chemical nature, including a description of its optimum pH (6.0 to 7.0) and temperature (2030°C). Furthermore, ion effects on ZSA activity were also determined, show- ing that three divalent ions (Mn2+, Ca2+, and Ba2+) were able to enhance starch hydrolysis. Fe2+ appeared to decrease a- amylase activity by half. ZSA kinetic parameters were also determined and compared to other insect a-amylases. A three-dimensional model is proposed in order to indicate probable residues involved in catalysis (Asp204, Glu240, and Asp305) as well other important residues related to starch binding (His118, Ala206, Lys207, and His304). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 61:7786, 2006. © 2006 Wiley-Liss, Inc. KEYWORDS: Zabrotes subfasciatus; a-amylase; molecular modelling; enzyme activity; bean bruchid INTRODUCTION severe damage to seed and seedpods.