Composers Speaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

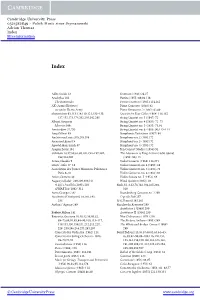

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Graå»Yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Gra#yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions: From a Perspective of Music Performance Hui-Yun (Yi-Chen) Chung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ AND HER VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS- FROM A PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE By HUI-YUN (YI-CHEN) CHUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Hui‐Yun Chung defended this treatise on November 3, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above‐named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my beloved family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Professor Eliot Chapo for his support and guidance in the completion of my treatise. I also thank my committee members, Dr. James Mathes and Professor Melanie Punter, for their time, support and collective wisdom throughout this process. I would like to give special thanks to my previous violin teacher, Andrzej Grabiec, for his encouragement and inspiration. I wish to acknowledge my great debt to Dr. John Ho and Lucy Ho, whose kindly support plays a crucial role in my graduate study. I am grateful to Shih‐Ni Sun and Ming‐Shiow Huang for their warm‐hearted help. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Abstracts Euromac2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014

Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens 2014 Euro Leuven MAC Eighth European Music Analysis Conference 17-20 September 2014 Abstracts EuroMAC2014 Eighth European Music Analysis Conference Leuven, 17-20 September 2014 www.euromac2014.eu EuroMAC2014 Abstracts Edited by Pieter Bergé, Klaas Coulembier, Kristof Boucquet, Jan Christiaens Graphic Design & Layout: Klaas Coulembier Photo front cover: © KU Leuven - Rob Stevens ISBN 978-90-822-61501-6 A Stefanie Acevedo Session 2A A Yale University [email protected] Stefanie Acevedo is PhD student in music theory at Yale University. She received a BM in music composition from the University of Florida, an MM in music theory from Bowling Green State University, and an MA in psychology from the University at Buffalo. Her music theory thesis focused on atonal segmentation. At Buffalo, she worked in the Auditory Perception and Action Lab under Peter Pfordresher, and completed a thesis investigating metrical and motivic interaction in the perception of tonal patterns. Her research interests include musical segmentation and categorization, form, schema theory, and pedagogical applications of cognitive models. A Romantic Turn of Phrase: Listening Beyond 18th-Century Schemata (with Andrew Aziz) The analytical application of schemata to 18th-century music has been widely codified (Meyer, Gjerdingen, Byros), and it has recently been argued by Byros (2009) that a schema-based listening approach is actually a top-down one, as the listener is armed with a script-based toolbox of listening strategies prior to experiencing a composition (gained through previous style exposure). This is in contrast to a plan-based strategy, a bottom-up approach which assumes no a priori schemata toolbox. -

Erica Amelia Reiter

Krzysztof Penderecki's Cadenza for Viola Solo as a derivative of the Concerto for Viola and Orchestra: A numerical analysis and a performer's guide Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Reiter, Erica Amelia, 1968- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 13:40:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289622 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^ewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproductioii is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the origmal, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

PENDERECKI Utrenja

572031 bk Penderecki 4/2/09 16:15 Page 8 Stanisław Skrowaczewski, and in 1958 Witold Rowicki was again appointed artistic director and principal conductor, a post he held until 1977, when he was succeeded by Kazimierz Kord, serving until the end of the centenary celebrations in 2001. In 2002 Antoni Wit became general and artistic director of the Warsaw PENDERECKI Philharmonic – The National Orchestra and Choir of Poland. The orchestra has toured widely abroad, in addition to its busy schedule at home in symphony concerts, chamber concerts, educational work and other activities. It now has a complement of 110 players. Utrenja Antoni Wit Hossa • Rehlis • Kusiewicz • Nowacki • Bezzubenkov Antoni Wit, one of the most highly regarded Polish conductors, studied conducting with Henryk Czyz and composition with Krzysztof Penderecki Warsaw Boys’ Choir at the Academy of Music in Kraków, subsequently continuing his studies with Nadia Boulanger in Paris. He also graduated in law at the Jagellonian University in Kraków. Immediately after completing his studies he was Warsaw Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra engaged as an assistant at the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra by Witold Rowicki and was later appointed conductor of the Poznan Philharmonic, Antoni Wit collaborated with the Warsaw Grand Theatre, and from 1974 to 1977 was artistic director of the Pomeranian Philharmonic, before his appointment as director of the Polish Radio and Television Orchestra and Chorus in Kraków, from 1977 to 1983. From 1983 to 2000 he was the director of the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra in Katowice, and from 1987 to 1992 he was the chief conductor and then first guest conductor of Orquesta Filarmónica de Gran Canaria. -

Piano Concerto ‘Resurrection’ Flute Concerto Barry Douglas, Piano • Łukasz Długosz, Flute Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Krzysztof Penderecki (B

PENDERECKI Piano Concerto ‘Resurrection’ Flute Concerto Barry Douglas, Piano • Łukasz Długosz, Flute Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Krzysztof Penderecki (b. 1933) momentum rapidly tails off and a plaintive idea for cor conducting the Lausanne Chamber Orchestra (a Piano Concerto ‘Resurrection’ • Concerto for Flute and Chamber Orchestra anglais emerges against wistful arabesques from the transcription for clarinet was made two years later). As soloist and soulful harmonies for orchestra. At length the with those other concertos involving wind rather than Kryzsztof Penderecki was born in Dubica on 23rd Written for Isaac Stern (who once declared that it ranked earlier impetus is regained and another forcef3ul climax is string instruments, the present work is relatively modest in November 1933, studying at the Kraków Academy of among the most important such concertos from the later arrived at before being suddenly curtailed to leave length and instrumentation, though the chamber Music then the Jagiellonian University, before twentieth century), it has remained among the most brusque gestures between the soloist and an array of orchestra is deployed with considerable resource while establishing himself at the Warsaw Autumn Festivals of frequently performed of all Penderecki’s pieces, and was percussion, with sardonic woodwind also m4aking its the emotional range is wider than that often associated 1959 and 1960. He soon became part of the European presently followed by the hardly less emotionally intense presence felt. A further climax is denied by the with the flute. There are five movements, again played avant-garde , achieving a notable success with Threnody Second Cello Concerto written for Mstislav Rostropovich, implacable intervention of brass and lower strings, the without pause and often with notable deviations from the [Naxos 8.554491] in which he imparted an intensely the smaller-scale Viola Concerto [both 8.572211] and the soloist continuing in uncertainty against an atmospheric tempo heading. -

Perceptual and Semantic Dimensions of Sound Mass

PERCEPTUAL AND SEMANTIC DIMENSIONS OF SOUND MASS Jason Noble Composition Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal April 2018 A dissertation submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Jason Noble 2018 In memory of Eleanor Stubley, Clifford Crawley, and James Bradley, for whose guidance and inspiration I am eternally grateful Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................................v Résumé ................................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgments................................................................................................................xi Contributions of Authors ......................................................................................................xiii List of Figures ......................................................................................................................xiv List of Tables .......................................................................................................................xvii Introduction ....................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Perceptual Dimensions of Sound Mass .............................................5 1.1 Introduction: Defining ‘Sound Mass’ .........................................................................5 -

Blázen Nebo Génius? Krzysztof Penderecki – a Freak Or a Genius?

Středoškolská odborná činnost Obor SOČ: 15. teorie kultury, umění a umělecké tvorby Krzysztof Penderecki – blázen nebo génius? Krzysztof Penderecki – a freak or a genius? Autor: David Šimeček Škola: Gymnázium J. V. Jirsíka, Fráni Šrámka 23, 371 46 České Budějovice Konzultant: Mgr. Olga Thamová České Budějovice 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem předloženou práci vypracoval samostatně, použil jsem podklady (literaturu, SW) uvedené v přiloženém seznamu a postup při zpracování a dalším nakládání s prací je v souladu se zákonem č. 121/2000 Sb., o právu autorském, o právech souvisejících s právem autorským a o změně některých zákonů (autorský zákon) v platném znění. V ………… dne …………………… podpis:…………….………………………. Poděkování Děkuji vedoucí mojí práce paní Mgr. Olze Thámové za konzultace a poskytnutou literaturu, dále pak paní Mgr. Petře Nové a paní Evě Mezerové za přínosné prameny a připomínky k mé práci. Anotace Tato práce se zabývá současným polským autorem klasické hudby Krzysztofem Pendereckim. V úvodních kapitolách se zaměřuje na jeho pozici v polské poválečné hudbě a popisuje jeho život. Zbytek práce je zaměřen zejména na jeho dílo – najdeme zde rozbor zřejmě nejznámější skladby Tren, různé zajímavosti jako např. způsob notace tohoto autora, nástrojové obsazení jeho orchestrů nebo použití jeho hudby ve filmu. Závěr práce tvoří dotazník, který byl vyplněn studenty našeho gymnázia. Klíčová slova: Penderecki, polská hudba, Tren, obsazení orchestru Obsah 1. Úvod .........................................................................................................................