Featured National Historic Landmarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUNE 1962 The

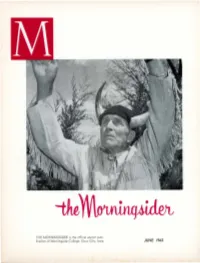

THE MORNINGSIDERis the official alumni publ- ication of Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa JUNE 1962 The President's Pen The North Iowa Annual Conference has just closed its 106th session. On the Cover Probably the most significant action of the Conference related to Morningside and Cornell. Ray Toothaker '03, as Medicine Man Greathealer, The Conference approved the plans for the pro raises his arms in supplication as he intones the chant. posed Conference-wide campaign, which will be conducted in 1963 for the amount of $1,500,000.00, "O Wakonda, Great Spirit of the Sioux, brood to be divided equally between the two colleges over this our annual council." and used by them in capital, or building programs. For 41 years, Mr. Toothaker lhas played the part of Greathealer in the ceremony initiating seniors into The Henry Meyer & Associates firm was em the "Tribe of the Sioux". ployed to direct the campaign. The cover picture was taken in one of the gardens Our own alumnus, Eddie McCracken, who is at Friendship Haven in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where Ray co-chairman of the committee directing the cam resides. Long a highly esteemed nurseryman in Sioux paign, was present at the Conference during the City, he laid out the gardens at Friendship Haven, first three critical days and did much in his work plans the arrangements and supervises their care. among laymen and ministers to assure their con His knowledge and love of trees, shrubs and flowers fidence in the program. He presented the official seems unlimited. It is a high privilege to walk in a statement to the Conference for action and spoke garden with him. -

Qlocation of Legal Description Courthouse

Form NO to-30o <R«V 10-74) 6a2 « Great Explorers of the West: Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-6 UNITtDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Sergeant Floyd Monument AND/OR COMMON Sergeant Floyd Monument LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glenn Avenue and Louis Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Sioux City _J£VICINITY OF 006 faixthl STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 19 Woodbury 193 {{CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_puBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILD ING<S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _?PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -3PES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: j ' m OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME (jSioux City Municipal Government) Mr. Paul Morris, Director Parks and Recreatl STREET & NUMBER Box 447, City Hall CITY. TOWN STATI Sioux City _ VICINITY OF Iowa 51102 QLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Wbodbury County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Sioux City Iowa REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE 1955 X.FEDERAL .....STATE _COUNTY ....LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Sites Survey, 1100 L . Street, NW. CITY. TOWN Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE JCGOOD (surrounding RUINS .XALTERED MOVED DATE 1857 _FAIR area) _ UNEXPOSED x eroded x destroyed DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Sergeant Charles Floyd died August 20, 1804 and was buried on a bluff over looking the Missouri River from its northern bank. -

Lewis and Clark Trust a Friends Group for the Trail

JUNE 2013 A NEWSLETTER OF LEWIS anD CLARK NATIOnaL HISTORIC TRAIL Effective Wayshowing Pgs. 4-6 From the Superintendent Where is the Trail? What is the Trail? want to know. But then there are those who want to know exactly where the trail is…meaning where is the path that Lewis and Clark walked on to the Pacific? This is not such an easy question to answer. Part of the difficulty with this question is that with few exceptions we do not really know exactly where they walked. In many cases, some members of the expedition were Mark Weekley, Superintendent on the river in watercraft while others were on land at the same time. This question One of the interesting questions I get from is also problematic because it is often time to time is, “Where is the Trail?” This based in a lack of understanding of what a seems like an easy enough question to National Historic Trail is and how the Lewis answer. My first instinct is to hand someone and Clark expedition moved through the our brochure with a map of the trail on landscape. Some folks have an image of the back, or to simply say the trail runs Lewis and Clark walking down a path single from Wood River, Illinois, to the mouth of file with Sacajawea leading the way. To them the Columbia River on the Oregon Coast. it would seem that the National Historic Sometimes this seems to be all people Trail would be a narrow path which is well 2 defined. If a building or road has been built This raises the obvious question, “What is in this location then “the trail” is gone. -

Field Notes7-2007#23.Pub

July 2007 Wisconsin’s Chapter ~ Interested & Involved Number 23 During this time in history: (July 4th, 1804/05/06) (The source for all Journal entries is, "The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedi- tion edited by Gary E. Moulton, The Uni- versity of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001.) By: Jack Schroeder July 4, 1804, (near today’s Atchison, Kan- sas) Clark: “Ushered in the day by a dis- charge of one shot from our bow piece, A worthwhile tradition was re- th proceeded on…Passed a creek 12 yards invigorated Saturday June 16 when wide…as this creek has no name, and this the Badger Chapter held a picnic for th being the 4 of July, the day of the inde- about 30 members and guests at the pendence of the U.S., we call it Independ- ence Creek…We closed the day by a dis- Horicon Marsh Environmental Educa- charge from our bow piece, an extra gill tion Barn. The location was widely of whiskey.” approved for the coolness of the inte- rior, the rustic feel of the stone walls, July 4, 1805, (at the Great Falls, Montana) Lewis: “Our work being at an end this and the sweeping view of the marsh. evening, (most men were working on the iron boat) we gave the men a drink of The potluck lunch featured four au- spirits, it being the last of our stock, and thentic Lewis and Clark recipes in- some of them appeared a little sensible of cluding a couple of bison dishes. The it’s effects. The fiddle was plied and they danced very merrily until 9 in the evening highlight of the meal was the two ta- when a heavy shower of rain put an end to bles groaning under the weight of that part of the amusement, though they dozens of excellent salads and des- continued their mirth with songs and fes- serts. -

Lewis & Clark Timeline

LEWIS & CLARK TIMELINE The following time line provides an overview of the incredible journey of the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Beginning with preparations for the journey in 1803, it highlights the Expedition’s exploration of the west and concludes with its return to St. Louis in 1806. For a more detailed time line, please see www.monticello.org and follow the Lewis & Clark links. 1803 JANUARY 18, 1803 JULY 6, 1803 President Thomas Jefferson sends a secret letter to Lewis stops in Harpers Ferry (in present-day West Virginia) Congress asking for $2,500 to finance an expedition to and purchases supplies and equipment. explore the Missouri River. The funding is approved JULY–AUGUST, 1803 February 28. Lewis spends over a month in Pittsburgh overseeing APRIL–MAY, 1803 construction of a 55-foot keelboat. He and 11 men head Meriwether Lewis is sent to Philadelphia to be tutored down the Ohio River on August 31. by some of the nation’s leading scientists (including OCTOBER 14, 1803 Benjamin Rush, Benjamin Smith Barton, Robert Patterson, and Caspar Wistar). He also purchases supplies that will Lewis arrives at Clarksville, across the Ohio River from be needed on the journey. present-day Louisville, Kentucky, and soon meets up with William Clark. Clark’s African-American slave York JULY 4, 1803 and nine men from Kentucky are added to the party. The United States’s purchase of the 820,000-square mile DECEMBER 8–9, 1803 Louisiana territory from France for $15 million is announced. Lewis leaves Washington the next day. Lewis and Clark arrive in St. -

Major Masterpiece

SPRING/SUMMER 2014 BREWING UP BUSINESS MAJOR MASTERPIECE A SEMIANNUAL PUBLICATION FOR CITIZENS OF SIOUX CITY, IOWA CREATING CONNECTIONS LANDMARK LIVING NEW FRONTIERS FOR AIR TRAVEL Sioux City airport travelers can now look to the west for travel options. Effective June 12, Frontier HOUSING ON THE RISE Airlines is launching regular nonstop service to its primary hub in Denver—two years after American Eagle Sioux City has seen record-breaking residential growth for the second year added regular nonstop service to Chicago. in a row! There were 107 housing units built last year, about 25% higher than “We are pleased Frontier Airlines approached us the previous high of 81 units in 2012. to offer renewed service to our community,” said Curt “Having strong numbers last year, and even stronger numbers this year, Miller, Sioux City airport director. “Its return provides The first business in Southbridge Business Park, Sabre Industries is expanding its large campus with new facilities. indicates a trend that reflects overall growth and strength of our local economy,” says Councilmember Pete Groetken. Sioux City travelers with a west coast connection to Featuring tall ceilings, large windows, and hardwood floors, the Williges complement our successful routes to the east.” Lofts offer new market-rate living options in downtown Sioux City. Developers are already planning subdivisions in Leeds, Northside, and Frontier’s 138-seat Airbus 319 aircraft feature Morningside, with further housing construction anticipated next year. amenities such as STRETCH for additional legroom and Any new home built in Sioux City qualifies for tax abatement for up to 10 SABRE SUCCESS CONTINUES years—a perk that has likely spurred residential growth in the community. -

5 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A 4

NPS Form 10-900 0MB'No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Downtown Waycross Historic District other names/site number n/a 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by the railroad corridor on the east and south, Albany and Isabella Streets on the north, and Remshart and Nicholls Streets on the west. city/ town Waycross (n/a) vicinity of county Ware code GA 299 state Georgia code GA zip code 31501 (n/a) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: (x) private (x) public-local ( ) public-state ( ) public-federal Category of Property ( ) building(s) (x) district ( ) site ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributina buildings 47 15 sites 2 0 structures 2 2 objects 3 1 total 54 18 Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 5 Name of related multiple property listing: n/a 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nonination Meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and Meets the procedural and professional requi reMents set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

2018 Charles City, Iowa Comprehensive Plan

Home of The Comets 2018 Charles City, Iowa Comprehensive Plan Prepared By North Iowa Area Council Of Governments (NIACOG) And the City of Charles City Charles City Comprehensive Plan - 2018 CKNOWLEDGEMENTS A ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A special thanks to the Task Force Participants and the Citizens of Charles City who participated in creating this plan. (TF = Task Force Committee Member) Mayor & City Council City Council Dr. Dan Cox, Charles City Schools Mayor Dean Andrews & James Erb (TF) Mike Fisher, Charles City Schools Councilman DeLaine Freeseman Tim Fox, Charles City Area Development Councilman Michael Hammond (TF) Corporation Councilman Jerry Joerger Eric Whipple, Fire Chief Councilman Dan Mallaro Lezlie Weber, County EMA Director Councilman Keith Starr Cathy Rottinghaus, First Citizens Bank Dusty Rolando, County Engineer Dirk Uetz, Streets Superintendent City Staff Bill Kyle, Airport Director Steven Diers, City Administrator (TF) Frank Blaine, Valero Renewable Fuels Trudy O’Donnell, City Clerk Dan Rimrod, City Waste Water Treatment Plant John D. Fallis, City Engineer (TF) Dean Stewart, Realtor Heidi Nielsen, Housing Director (TF) Wendy Johnson, Farmer Eric Whipple, Fire Chief (TF) Kurt Herbrechtsmeyer, First Security Bank Dan Rimrod, Water Pollution Control Bob Kloberdanz, Parks & Recreation Board Superintendent (TF) Randy Heitz, Agriculture Steve Lindaman, Parks & Recreation Dir. (TF) Mark Wicks, Charles City Economic Hugh Anderson, Police Chief (TF) Development Dirk Uetz, Street Superintendent (TF) Chris -

The Historic Sites Survey and National Historic Landmarks Program

File D-286 NPS General THE HISTORIC SITES SURVEY AND NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM A HISTORY by Barry Mackintosh PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER ON MICROFILM DENVER SERVJCE CENTER Color Scans NATIONALPARK SERVICE 1/17/2003 THE HISTORIC SITES SURVEY AND NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS PROGRAM A HISTORY by Barry Mackintosh History Division National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1985 CONTENTS PREFACE •• . V THE PREWAR YEARS . 1 Setting the Framework • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Conduct of the Survey ••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Marking: The Blair House Prototype •••••••••••••• 22 POSTWAR INITIATIVES AND THE LANDMARKS PROGRAM . 27 Efforts at Resumption ••••••••••••••••••••• 27 The Proposed National Trust Connection ••••••••••••• 29 Mission 66 and Reactivation of the Survey • • • •••••• 32 Landmark Designation •••••••••••••••••••••• 37 The First National Historic Landmark •••••••••••••• 41 Landmarks Progress: Plaques and More "Firsts" • • • • • • • • • 46 THE PROGRAM PERPETUATES • . 57 Survival of the Survey ••••••••••••••••••••• 57 Broadening the Criteria •••••••••••••••••• 69 The Black Landmarks and Other Departures •••••••••••• 72 Presidential Landmarks ••••••••••••••••••••• 85 The Publications Program ••••••••••••••••• ••• 89 Landmarks in the National Park System ••••••••••••• 94 Green Springs and Its Consequences ••••••••••••••• 97 Landmark Inspection and De-designation ••••••••••••• 102 Commercial Landmarks and Owner Consent •••••••••••••107 The Program at Its Half-Century ••••••••••••••••112 -

Fall 2013 Timeline Newsletter

Fall 2013 • Vol. 2, Issue 5 Museum partners with local schools o reach wider audiences In addition, Museum staff of students and teach- are working with students Ters, the Sioux City Public and teachers representing Museum is developing sev- North High’s Multicultural eral collaborative efforts with Club to develop a film for area educational groups. Martin Luther King Jr. Day In November, the Museum activities that will be shown hosted two events for the to high school students in Sioux City Community School Sioux City schools. While District’s middle and high the film will feature na- School STEM (Science, Tech- tional civil rights and Martin nology, Engineering, and Luther King Jr. stories, it will Math) programs. A demon- emphasize civil rights sto- Students involved in the Sioux City Community stration from middle school ries from Sioux City, includ- School’s STEM program explained their robotics and high school students ing local interviews. The to Lt. Governor Kim Reynolds as School Board President Mike Krysl and Superintendent Paul involved in the STEM program film will also include per- Gausman looked on. was presented to Lt. Gover- spectives on the “I Have a nor Kim Reynolds at the Mu- Dream” speech from current education staff. The one-hour seum. Reynolds noted that students. The 20-minute film programs include hands-on the Sioux City school district will have its premiere at the time in the galleries, short was one of the first districts in Sioux City Public Museum on education programs in the the state to hire STEM coach- Sunday, January 19 at 2 p.m. -

Your Guide to Siouxland's Best Things to Do

SumMeR fuN YOUR GUIDE TO SIOUXLAND’S BEST THINGS TO DO A 2020 SIOUX CITY JOURNAL SPECIAL SECTION S2 | 2020 EDITION 101 THINGS TO DO IN SIOUXLAND SUMMER GUIDE TO Lake View It’s a lifestyle. LAKE VIEW 67th Annual Black Hawk Lake Stone Pier Concert Series Summer Water Carnival Bring your chairs or blankets to the natural amphitheater surrounding the west Stone Pier in the Town Bay of Black Hawk Lake. You’ll enjoy great live music in a beautiful natural setting. There is no admission charge or ticket required to attend the shows, thanks to the support of the Series’ many generous sponsors. While concertgoers may bring food and beverages to the picnic-style performances, food is for sale at each show with 100% of proceeds going back to the event. The Lake View Fire Department operates the official “Burger Boat,” which July 17 & 18, 2020 delivers food to fans watching from Black Hawk Lake. Join us for three concerts in the Summer of 2020. Theme: Lake View: A Great Place to Saturday, July 4th Drop Anchor Celebrate Independence Day at the Pier! Four bands will rock the Pier beginning at 4:00 p.m. Blue Water Highway We’re still working to finalize the schedule for Blue Water Highway comes from the working class, coastal town background that has informed the work of so many of rock’s greatest writers and artists. They take their name from the roadway that links their hometown of Lake Jackson, Texas, to Galveston, and their music is the soundtrack for their lives. -

The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc

The Official Publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. Vol. 21 . No. 3 August 1995 THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. In this issue- Incorporated 1969 under Missouri General Not-For-Profit Corporation Act IRS Exemption Certificate No. 501(C)(3) -ldentification No. 51 -0187715 - OFFICERS A.CTIVE PA.ST PRESIDENTS Page 3- President Irving W. Anderson Robert E. Garren. Jr. Pol"lland. 01'egon Searching for the Invisible: 3507 Smokecree Drive Robert K. Doerk, Jr . Greensboro. NC 2741 0 G1'eat Falls, Montana Some Efforts to Find Second Vice President James R. Fazio Expedition Camps Ella Mae Howard Moscow. Idaho 1904 4th Sc. N.W. V. Scrode Hinds Ken Karsmizki Grear Falls. MT 59404 Sioux City. Iowa Secretary Arlen j. Large Barbara Kubik Washington. D.C. Page 12- I 712 S. Perry Court H. John Monrague J~e nnewick, WA 99337 Portland, Oregon Lewis & Clark Meet the Treasurer Donald F. Nell "American Incognitum" H. j ohn Montague Bozeman. Montana 2928 NW Verde Visca Terrace William P. Sherman Arlen J. Large Portland. OR 972 I 0·3356 Portland. Oregon Immediate Past President L. Edwin Wang Minneapolis, Minnesora Scuarc E. Knapp Page 18- t 3 t 7 South Black Wilbur P. Werner Bozeman . M T 59715 Mesa. A1'izona Monument for a Sergeant DIRECTORS A.T LA.RGE Strode Hinds David Borlaug Harry Hubbard Darold W. Jackson James M . Peterson Washburn. Nonh Dakota Seanle. Washington Sc. Charles, Missouri Vermillion. Smuh Dakow Judith Edwards Clyde G. Huggins Ronald G. Laycock Ludd A. Trozpek Glen Head. New )'brk Mandevi!fe.