The Historic Sites Survey and National Historic Landmarks Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

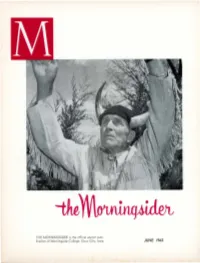

JUNE 1962 The

THE MORNINGSIDERis the official alumni publ- ication of Morningside College, Sioux City, Iowa JUNE 1962 The President's Pen The North Iowa Annual Conference has just closed its 106th session. On the Cover Probably the most significant action of the Conference related to Morningside and Cornell. Ray Toothaker '03, as Medicine Man Greathealer, The Conference approved the plans for the pro raises his arms in supplication as he intones the chant. posed Conference-wide campaign, which will be conducted in 1963 for the amount of $1,500,000.00, "O Wakonda, Great Spirit of the Sioux, brood to be divided equally between the two colleges over this our annual council." and used by them in capital, or building programs. For 41 years, Mr. Toothaker lhas played the part of Greathealer in the ceremony initiating seniors into The Henry Meyer & Associates firm was em the "Tribe of the Sioux". ployed to direct the campaign. The cover picture was taken in one of the gardens Our own alumnus, Eddie McCracken, who is at Friendship Haven in Fort Dodge, Iowa, where Ray co-chairman of the committee directing the cam resides. Long a highly esteemed nurseryman in Sioux paign, was present at the Conference during the City, he laid out the gardens at Friendship Haven, first three critical days and did much in his work plans the arrangements and supervises their care. among laymen and ministers to assure their con His knowledge and love of trees, shrubs and flowers fidence in the program. He presented the official seems unlimited. It is a high privilege to walk in a statement to the Conference for action and spoke garden with him. -

EXHIBIT a to KING DECLARATION: Second Amended Complaint

Case 2:12-cv-01079-MHT-CSC Document 159-2 Filed 06/05/19 Page 1 of 80 EXHIBIT A TO KING DECLARATION: Second Amended Complaint Case 2:12-cv-01079-MHT-CSC Document 159-2 Filed 06/05/19 Page 2 of 80 The Honorable Myron H. Thompson UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA NORTHERN DIVISION MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION, a federally recognized Indian tribe, HICKORY GROUND TRIBAL TOWN, and MEKKO GEORGE THOMPSON, individually and as traditional 2:12-cv-1079-MHT-CSC representative of the lineal descendants of those buried at Hickory Ground Tribal Town in Wetumpka, Alabama. SECOND AMENDED COMPLAINT AND Plaintiffs, SUPPLEMENTAL v. COMPLAINT POARCH BAND OF CREEK INDIANS, a federally recognized tribe; STEPHANIE A. BRYAN, individually and in her official capacity as Chair of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians (“Poarch”) Tribal Council; ROBERT R. MCGHEE, individually and in his official capacity as Vice Chair of Poarch Tribal Council; EDDIE L. TULLIS, individually and in his official capacity as Treasurer of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; CHARLOTTE MECKEL, in her official capacity as Secretary of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; DEWITT CARTER, in his official capacity as At Large member of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; SANDY HOLLINGER, individually and in her official capacity as At Large member of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; KEITH MARTIN, individually and in his official capacity as At Large member of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; ARTHUR MOTHERSHED, individually and in his official capacity as At Large member of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; GARVIS SELLS, individually and in his official capacity as At Large member of the Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Council; BUFORD ROLIN, an individual; DAVID GEHMAN, an individual; LARRY HAIKEY, in his official capacity as Acting Poarch Band of Creek Indians Tribal Historic Preservation Officer; PCI GAMING AUTHORITY d/b/a WIND CREEK HOSPITALITY; WESTLY L. -

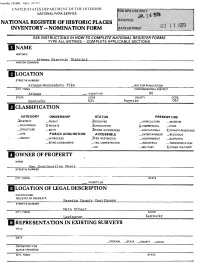

National Register of Historic Places Registration

NFS Form 10-900 OMB NO. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service AU6-820GO National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NA1 REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES ' NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____ Four Corners Historic District historic name N/A other names/site number 2. Location__________________________________________ street & number Roughly bounded by Raymond Blvd., Mulberry St., Hf St. & Washington Stn not for publication city or town Newark_____________________________________________ D vicinity state. New Jersey______ __ __ codeii NJ county Essex code °13 zip code 07102 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended. I hereby certify that this B nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property B meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs

1963 Chevrolet Impala, Owner Lee Cordova of Alcalde, NM, 1998. Jack Parsons, photographer. Palace of the Governors Photo Archives HP.2007.11. NEW MEXICO DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS Presentation to the Legislative Finance Committee July 27, 2016, Ruidoso FOUNDED IN 1909 AS THE MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO, DCA’S ORIGINS PREDATE THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO ITSELF. The interior courtyard of Santa Fe’s Palace of the Governors, the oldest public building in the country. The Department of Cultural Affairs is New Mexico’s cultural steward—charged with preserving and showcasing the state’s cultural riches. With its eight museums, eight historic sites, arts, historic preservation, archaeology and library programs, New Mexico’s Department of Cultural Affairs is among the most ambitious and respected state cultural agencies in the nation. Together, the facilities, programs and services of the department see over 1.2 million visitors annually and help support a $5.6 billion cultural industry in New Mexico. The Department is divided into five programs and consists of 15 divisions. DCA owns and cares for 190 buildings comprising 1.3 million square feet on 16 campuses totaling over 1,000 acres. Its facilities are located throughout the state with programs and services reaching every county in New Mexico. The Department’s annual budget is approximately $39.5 million, of which $29.4 million is General Fund. 2 MUSEUMS AND HISTORIC SITES PROGRAM In communities across New Mexico, the state’s eight museums and eight Historic Sites interpret, celebrate, and present -

Historic Sod House Ranch Malheur National Wildlife Refuge/Oregon

Historic Sod House Ranch Malheur National Wildlife Refuge/Oregon Sod House Ranch is an intact 1880s era cattle ranch constructed and managed by cattle baron Peter French. At the peak of its operation, it was the largest cattle ranch on private property in the United States. Today, this historical legacy is preserved at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, where it serves showcases the cattle ranching heritage of southeastern Oregon. The ranch, particularly its unique long barn (Figure 3), has been the focus of restoration efforts for the past five years. Despite its location more than 160 miles from the nearest urban center, this spectacular barn has drawn the interest and support of many diverse partners, including the University of Oregon Architectural Field School, AmeriCorps, Oregon State Parks and Recreation Department, Harney County Historical Society, Malheur Wildlife Associates, the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office; National Park Service, Architectural Division Youth Conservation Corps, and the High Desert Museum Teen Volunteers. Recently, the refuge hosted a Ranching Heritage Day at the site to celebrate completion of the barn restoration, as well as repairs to nine other buildings and construction of a Centennial Trail to facilitate visitation. The ranch has been the site of historical re-creations and has spurred a teaching curriculum and heritage education. It has received grant funding from the Service Challenge Cost Share program, Service Centennial Challenge Cost Share program, Preserving Oregon for Historic Properties, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. Figure 3. Long Barn at the Historic Sod Ranch . -

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 1995

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE P.O. Box 37127 ·washington, D.C. 20013-7127 I~ REPLY REFER TO: The Director of the National Park Service is pleased to inform you that the following properties have been entered in the National Register of Historic Places. For further information call 202/343-9542. JAN 6 1995 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/26/94 THROUGH 12/30/94'· KEY: State, County, Property Name, Address/Boundary, City, Vicinity, Reference Number NHL Status, Action, Date, Multiple Name ARIZONA, YAVAPAI COUNTY, Fleury's Addition Historic District, Roughly, Western and Gurley from Willow to Grove, and Willow, Garden and Grove, from Western to Gurley, Prescott vicinity, 94001488, NOMINATION, 12/27/94 (Prescott MRA) CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES COUNTY, Lanterman House, 4420 Encinas Dr., La Canada Flintridge, 94001504, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, MONTEREY COUNTY, Pacific Biological Laboratories, 800 Cannery Row, Monterey, 94001498, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, ORANGE COUNTY,. Huntington Beach Elementary School Gymnasium and Plunge, 1600 Palm Ave., Huntington Beach, 94001499, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY, Smiley Park Historic District, Roughly bounded by Brookside Ave., Cajon St., Cypress Ave. ami Buena Vista St., Redlands, 94001487, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, SAN MATEO COUNTY, Brittan, Nathanial. Party House, 125 Dale Ave., San Carlos, 94001500, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, SONOMA COUNTY, Rosenburg's Department Store, 700 Fourth St., Santa Rosa, 94001497, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 CALIFORNIA, STANISLAUS COUNTY, Hotel Covell, 1023 J St., Modesto, 94001501, NOMINATION, 12/29/94 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA STATE EQUIVALENT, Carnegie Institution of Washington. -

Gordon Bond All Were Created by Sculptors Who Also Have Celebrated Works in Newark, New Jersey

Sitting in Military Park, at the heart of Newark’s downtown revival, Gutzon Borglum’s 1926 “Wars of America” monumental bronze is far more subtle than its massive size suggests, and possessing of a fascinating and complicated history few who pass by it each day are aware of. hat does Mount Rushmore, the Washington quarter, W and New York's famed Trinity Church Astor Doors all have in common? Gordon Bond All were created by sculptors who also have celebrated works in Newark, New Jersey. When people hear "Newark," they almost gardenstatelegacy.com/Monumental_Newark.html certainly don't think of a city full of monuments, memorials, and statuary by world renowned sculptors. Yet it is home to some forty-five public monuments reflecting a surprising artistic and cultural heritage—and an underappreciated resource for improving the City's image. With recent investment in Newark's revitalization, public spaces and the art within them take on an important role in creating a desirable environment. These memorials link the present City with a past when Newark was among the great American metropolises, a thriving center of commerce and culture standing its ground against the lure of Manhattan. They are a Newark’s “Wars of America” | Gordon Bond | www.GardenStateLegacy.com Issue 42 December 2018 chance for resident Newarkers to reconnect with their city's heritage anew and foster a sense of pride. After moving to Newark five years ago, I decided to undertake the creation of a new guidebook that will update and expand on that idea. Titled "Monumental Newark," the proposed work will go deeper into the fascinating back-stories of whom or what the monuments depict and how they came to be. -

Comprehensive Plan P Age Intentionally Left Blank

2040 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN P AGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Mayor J OHNNY H AMMOCK City Council J EREMY T AUNTON S ARA H ILL D AMIAN C ARR D ARRELL W ILSON T ERREL D . B ROWN B ILL G OODWIN D AVID S TOUGH Acknowledgements Planning Commission B ETH T URNER , S ECRETARY T h a n k y o u to a l l of t h e individuals J OYCE V ELLA t h a t m a d e t h i s plan p o s s i b l e . M a y H ERBERT M ASON , V ICE- C HAIR it t r a n s f o r m T a l l a s s e e i n t o t h e c i t y W ILLIE S MITH t h e c i t i z e n s d e s i r e . C LIFF J ONES J OEY S CARBOROUGH J EREMY T AUNTON , C OUNCIL R EP. A NDY C OKER Plan Prepared by C ENTRAL A LABAMA R EGIONAL P LANNING AND D EVELOPMENT C OMMISSION Additional Thanks To: C ITY OF T ALLASSEE E MPLOYEES T ALLASSEE C ITY S CHOOL D ISTRICT A ND EACH CITIZEN OF T ALLASSEE WHO GAVE UP THEIR TIME TO HELP CREATE THIS PLAN . CITY OF TALLASSEE T REASURE ON THE T ALLAPOOSA “To provide a hi gh quality of life for our citizens while promoting balanced economic growth and preserving our natural beauty, diversity, and historic character.” - City of Tallassee Vision Statement CITY OF TALLASSEE 2040 Comprehensive Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 | BACKGROUND AND VISION HISTORY ......................................................................................................................... -

PALACE of the GOVERNORS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS Other Name/Site Number: SR 017 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Palace Avenue at Santa Fe Plaza Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Santa Fe Vicinity: N/A State: NM County: Santa Fe Code: 049 Zip Code: 87501 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: X Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 0 buildings 0 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

A Record-Breaking Year Members and Donors Give More Than Ever

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO FOUNDATION | WINTER 2017 A Record-Breaking Year Members and Donors Give More Than Ever THE 2016–17 FISCAL YEAR IN REVIEW Table of Contents LETTER TO MEMBERS 1 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2 THE 2016–17 FISCAL YEAR IN REVIEW 3 THE SCOOP 6 NEW MEXICO MUSEUM OF ART 7 Cover: THE CENTENNIAL CAMPAIGN 8 Top row, left to right: Photo © Kitty Leaken; NEW MEXICO HISTORY MUSEUM AND Photo courtesy New Mexico Department of PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS 10 Cultural Affairs; Photo © Andrew Kastner. MUSEUM OF INDIAN ARTS AND CULTURE 12 Middle: Photo © Kitty Leaken. MUSEUM OF INTERNATIONAL FOLK ART 14 Bottom row, left to right: Photo courtesy New OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES 16 Mexico Historic Sites; Photo © Daniel Quat NEW MEXICO HISTORIC SITES 18 Photography; Photo by Shayla Blatchford. ENDOWMENT FUNDS 20 MEMBERS AND DONORS 21 Below: A shopper admires a beautiful strand of YEAR-END GIVING 28 silver beads at the 2017 Native Treasures: Indian WAYS TO GIVE 29 Arts Festival. Photo © Jason Ordaz. Our Mission The Museum of New Mexico Foundation supports the Museum of New Mexico system through fund devel- opment for exhibitions and education programs, financial management, retail, licensing and advocacy. The Foundation serves the following state cultural institutions: • Museum of Indian Arts and Culture and Laboratory of Anthropology • Museum of International Folk Art • New Mexico History Museum and Palace of the Governors • New Mexico Museum of Art • New Mexico Historic Sites • Office of Archaeological Studies Member News Contributors Mariann Lovato, Managing Editor Carmella Padilla, Writer and Editor Alexandra Hesbrook Ramier, Writer Bram Meehan, Graphic Designer Saro Calewarts, Photographer Dear Members, This issue of Member News features our Annual Report on the membership, development, retail and licensing activities of the Museum of New Mexico Foundation during the 2016–17 fiscal year. -

Qlocation of Legal Description Courthouse

Form NO to-30o <R«V 10-74) 6a2 « Great Explorers of the West: Lewis and Clark Expedition, 1804-6 UNITtDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Sergeant Floyd Monument AND/OR COMMON Sergeant Floyd Monument LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glenn Avenue and Louis Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Sioux City _J£VICINITY OF 006 faixthl STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 19 Woodbury 193 {{CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_puBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILD ING<S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _?PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED -3PES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: j ' m OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME (jSioux City Municipal Government) Mr. Paul Morris, Director Parks and Recreatl STREET & NUMBER Box 447, City Hall CITY. TOWN STATI Sioux City _ VICINITY OF Iowa 51102 QLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Wbodbury County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Sioux City Iowa REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE 1955 X.FEDERAL .....STATE _COUNTY ....LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Sites Survey, 1100 L . Street, NW. CITY. TOWN Washington DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED —ORIGINAL SITE JCGOOD (surrounding RUINS .XALTERED MOVED DATE 1857 _FAIR area) _ UNEXPOSED x eroded x destroyed DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Sergeant Charles Floyd died August 20, 1804 and was buried on a bluff over looking the Missouri River from its northern bank. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Athens Historic, District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Athens-Boonesboro Pike —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Athens —.VICINITY OF 06 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Fayette 067 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .^DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) 3LPRIVATE J&JNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH J^WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY E-OTHER: Vacant OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Ton t- -in n at- -inn STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC ___Favette County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Main. CITY,TOWN STATE Lexington Kentucky REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Tl'TLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE CONDITION CHECK ONE JLEXCELLENT .^DETERIORATED (Parker HOUSe-)-UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED AMOVED DATElate 1800 T s. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED (Rose's Store) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The small community of Athens is located in the southeastern portion of Fayette County, ten miles southeast of Lexington and 6ne-quarter mile from the Interstate 75 interchange with Athens-Boonesboro Road. It lies in the midst of cultivated agricultural lands with several residences, primarily farm related, dotting the countryside.