The Effects of Napping on Night Shift Performance February 2000 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Development, Sound Aesthetics and Production Techniques of Metal’S Distorted Electric Guitar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository Historical development, sound aesthetics and production techniques of metal’s distorted electric guitar Jan-Peter Herbst Abstract The sound of the distorted electric guitar is particularly important for many metal genres. It contributes to the music’s perception of heaviness, serves as a distinguishing marker, and is crucial for the power of productions. This article aims to extend the research on the distorted metal guitar and on metal music production by combining both fields of interest. By the means of isolated guitar tracks of original metal recordings, 10 tracks in each of the last five decades served as sample for a historical analysis of metal guitar aesthetics including the aspects tuning, loudness, layering and spectral composition. Building upon this insight, an experimental analysis of 287 guitar recordings explored the effectiveness and effect of metal guitar production techniques. The article attempts to provide an empirical ground of the acous- tics of metal guitar production in order to extend the still rare practice-based research and metal-ori- ented production manuals. Keywords: guitar, distortion, heaviness, production, history, aesthetics Introduction With the exception of genres like black metal that explicitly value low-fidelity aesthetics (Ha- gen 2011; Reyes 2013), the powerful effect of many metal genres is based on a high production quality. For achieving the desired heaviness, the sound of the distorted electric guitar is partic- ularly relevant (Mynett 2013). Although the guitar’s relevance as a sonic icon and its function as a distinguishing marker of metal’s genres have not changed in metal history (Walser 1993; Weinstein 2000; Berger and Fales 2005), the specific sound aesthetics of the guitar have varied substantially. -

ABC's of Ios: a Voiceover Manual for Toddlers and Beyond!

. ABC’s of iOS: A VoiceOver Manual for Toddlers and Beyond! A collaboration between Diane Brauner Educational Assistive Technology Consultant COMS and CNIB Foundation. Copyright © 2018 CNIB. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this manual or portions thereof in any form whatsoever without permission. For information, contact [email protected]. Diane Brauner Diane is an educational accessibility consultant collaborating with various educational groups and app developers. She splits her time between managing the Perkins eLearning website, Paths to Technology, presenting workshops on a national level and working on accessibility-related projects. Diane’s personal mission is to support developers and educators in creating and teaching accessible educational tools which enable students with visual impairments to flourish in the 21st century classroom. Diane has 25+ years as a Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS), working primarily with preschool and school-age students. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in Rehabilitation and Elementary Education with certificates in Deaf and Severely Hard of Hearing and Visual Impairments. CNIB Celebrating 100 years in 2018, the CNIB Foundation is a non-profit organization driven to change what it is to be blind today. We work with the sight loss community in a number of ways, providing programs and powerful advocacy that empower people impacted by blindness to live their dreams and tear down barriers to inclusion. Through community consultations and in our day to -

Voice Overs: Where Do I Begin?

VOICE OVERS: WHERE DO I BEGIN? 1. WELCOME 2. GETTING STARTED 3. WHAT IS A VOICE OVER? 4. ON THE JOB 5. TODAY’S VOICE 6. UNDERSTANDING YOUR VOICE 7. WHERE TO LOOK FOR WORK 8. INDUSTRY PROS AND CONS 9. HOW DO I BEGIN? 2 WELCOME Welcome! I want to personally thank you for your interest in this publication. I’ve been fortunate to produce voice overs and educate aspiring voice actors for more than 20 years, and it is an experience I continue to sincerely enjoy. While there are always opportunities to learn something new, I feel that true excitement comes from a decision to choose something to learn about. As is common with many professions, there’s a lot of information out there about the voice over field. The good news is that most of that information is valuable. Of course, there will always be information that doesn’t exactly satisfy your specific curiosity. Fortunately for you, there are always new learning opportunities. Unfortunately, there is also information out there that sensationalizes our industry or presents it in an unrealistic manner. One of my primary goals in developing this publication is to introduce the voice over field in a manner that is realistic. I will share information based on my own experience, but I’ll also share information from other professionals, including voice actors, casting professionals, agents, and producers. And I’ll incorporate perspective from people who hire voice actors. After all, if you understand the mindset of a potential client, you are much more likely to position yourself for success. -

2021-01-14-RECON-IMAGER-Manual.Pdf

MANUAL 1.Introduction 4 2. Version Comparisons 4 3. Supported Hardware 6 3.1 MODE A - SUPPORTED HARDWARE (Version 4.0.0) 6 3.2 MODE B - BOOT SUPPORTED HARDWARE (Version 5.0.0) 6 3.3 MODE C - SUPPORTED HARDWARE (Version 5.0.2 A1) 7 4. Before You Start 7 4.1 How Will You Process The Image? 7 4.2 What To Image? 8 4.3 What Image Format Should I Use? 8 5. Key Concepts To Understand 9 5.1 Apple File System (APFS) 9 5.2 Apple Extended Attributes 9 5.3 Fusion Drives 10 5.4 Core Storage 10 5.5 FileVault 11 5.6 T2 Security Chipset 11 5.7 Local Time Machine Snapshots (APFS) 12 5.8 Apple Boot Camp 12 6. Booting RECON IMAGER 13 6.1 Instant On - Portable Macs 13 6.2 Firmware Password 13 6.3 Connecting RECON IMAGER 14 6.4 Connecting Your Destination Drive 15 6.5 Starting RECON IMAGER 15 7. Using RECON Imager 17 7.1 Disk Manager 18 7.1.1 Refresh To Detect Changes 19 RECON IMAGER Copyright © 2010-2020 SUMURI LLC 1 of 59 7.1.2 Formatting a Collection Drive 20 7.1.3 Decrypting A FileVault Volume 22 7.1.4 System Date and Time 24 7.2 Disk Imager 24 7.2.1 Source 25 7.2.2 Image Type 25 7.2.3 Compression Options 27 7.2.4 Processing Local Time Machine Snapshots (APFS) 27 7.2.5 Destination 28 7.2.6 Image Name 28 7.2.7 Segment Size 29 7.2.8 Evidence Descriptor Fields 29 7.2.9 Hashing and Verification 30 8. -

Youtube As a Virtual Springboard: Circumventing Gender Dynamics in Offline and Online Metal Music Careers

MMS 1 (3) pp. 303–318 Intellect Limited 2015 Metal Music Studies Volume 1 Number 3 © 2015 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/mms.1.3.303_1 PauwKe BerKers and Julian schaaP Erasmus University Rotterdam youTube as a virtual springboard: circumventing gender dynamics in offline and online metal music careers aBsTracT Keywords Studies have shown that learning to play in a band is largely a peer-based – rather gender inequality than individual – experience, shaped by existing sex-segregated friendship networks. online With the rise of the Internet and do-it-yourself recording techniques, new possibili- offline ties have emerged for music production and distribution. As male-dominated offline YouTube metal scenes are often difficult to enter for aspiring female metal musicians, online musical careers participation might serve as a possibility to circumvent these gender dynamics. This virtual springboard article therefore addresses to what extent female and male musicians navigate online metal scenes differently, and how this relates to the gender dynamics in offline metal scenes. By conducting ten in-depth interviews with women and men who produce vocal covers on YouTube, this article focuses on the understudied relationship between online and offline scene participation. Vocal covers are used for entertainment, skill development, online skill recognition and as a virtual springboard with which women in particular can (partially) circumvent gender inequality by allowing them to (initially) participate as individuals and pursue musical careers in metal music. 303 MMS_1.3_Berkers and Schaap_303–318.indd 303 8/8/15 6:31:41 PM Pauwke Berkers | Julian Schaap inTroducTion Music scenes in general – and metal scenes in particular – are highly stratified along gender lines. -

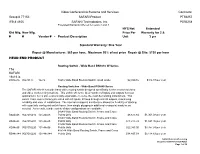

77153 4106 Safari Technologies Price List Dated December 2000

Video Conferencing Systems and Services Contracts: Group # 77153 SAFARI Product PT56257 IFB # 4106 SAFARI Technologies, Inc. PS56258 Extended Warranty Offered for years 2 and 3 NYS Net Extended Old Mfg. New Mfg. Price Per Warranty for 2 & # # Vendor # * Product Description Unit 3 yrs Standard Warranty: One Year Repair @ Manufacturer: $65 per hour, Maximum 50% of net price Repair @ Site: $130 per hour HEAD END PRODUCT Routing Switch - Wide Band DN1616 W Series The SAFARI 16x16 is DN16x16 00270177 16x16 16x16 Wide Band Routing Switch, small model $2,099.16 $314.87 per year Routing Switches - Wide Band RS4848 Series The SAFARI 48x48 is a wide band video routing switch designed specifically for the networked video and video conferencing markets. This switch offers the ideal number of inputs and outputs for most applications, but is also economically expandable to serve the most demanding installations. This switch frame comes factory pre-wired with 48 inputs, 48 loop through and 48 outputs, maximizing reliability and ease of installations. The internal crosspoint architecture allows the flexibility of starting with a partially configured switch frame, then simply plugging in additional crosspoint modules as needed. As a result, a wide variety of size configurations are available. 24x48 Wide Band Routing Switch, Frame and Cross RS24x48 9527016210 101-24x48 Points Only $8,673.84 $1,301.08 per year 48x48 Wide Band Routing Switch, Frame and Cross RS48x48 9527016201 101-48x48 Points Only $11,275.74 $1,691.36 per year 48x96 Wide Band Routing Switch, -

Alta Springboard

ALTA SPRINGBOARD Sponsorships & Vendor Registration ALTA SPRINGBOARD Date & Location Memphis, TN – March 20-21, 2019 - The Peabody CONFERENCE DESCRIPTION ALTA SPRINGBOARD takes attendees’ organizations and careers to the next level - it is the forum for fresh thinking, new insights and a big step forward. • NOTHING about this event is traditional • Two and a half day live-event experience where attendees will collaborate and be part of the conversation. Topics include Surviving the Silver Tsunami, Analyze Performance Metrics and Drive Innovation to Meet Customer Demands • ~300 attendees • Vendor space will be around the perimeter of the ideas festival room - where the discussion zones and breaks will take place- and in the foyer space. Space includes one branded demo kiosk, electricity, and wifi • Vendors will be asked to participate in the group conversations for a portion of the event • Sponsorship opportunities listed on the contract page (page 6) • Schedule information is available on our website: meetings.alta.org/springboard Important Dates & Times: WHO WILL BE THERE? Room Block Cut-Off • Meet face-to-face with more than 300 professionals within the land title industry • 2/19 Vendor Move In WHY SHOULD I COME? • Be a Part of the Conversation! • 3/19: 5:30 - 7:30 PM Be a part of round table discussions with potential customers as your assigned group problem solves on current industry issues. Use this time to make connnections and build client relationships. Vendor Move-Out • Gain New Business! • 3/21: 2:30 - 4:30 PM ALTA has introduced a new concept in networking—Brain Dating, engineered by E-180. -

Production Perspectives of Heavy Metal Record Producers Abstract

Production Perspectives of Heavy Metal Record Producers Dr Niall Thomas University of Winchester – [email protected] Dr Andrew King University of Hull – [email protected] Abstract The study of the recorded artefact from a musicological perspective continues to unfold through contemporary research. Whilst an understanding of the scientific elements of recorded sound is well documented the exploration of the production and the artistic nature of this endeavour is still developing. This article explores phenomenological aspects of producing Heavy Metal music from the perspective of seven renowned producers working within the genre. Through a series of interviews and subsequent in-depth analysis particular sonic qualities are identified as key within the production of this work: impact; energy; precision; and extremity. A conceptual framework is then put forward for understanding the production methodology of recorded Heavy Metal Music, and, how developing technology has influenced the production of the genre. Keywords: recording; Heavy Metal; production; producers; phenomenology Introduction The affordances of digital technology have significantly changed the opportunities for practicing musicians to record music. Technology enables even amateur music makers the opportunity to record music with relative ease. The democratisation of technology has meant that mobile devices can become pocket sized recording studios (Leyshon, 2009), whilst affordable solutions and emulations of prohibitively expensive computing and recording technology are readily available via the Internet. The technology associated with certain aspects of music making is now more widespread and enables a new sense of creative musical freedom; music producers command a limitless array of technological choices. Despite the benefits of the ever-increasing rate of technological development, the recording industry is changing dramatically, and with it, the production perspectives of record producers. -

The State of Vulkan on Apple 03June 2021

The State of Vulkan on Apple Devices Why you should be developing for the Apple ecosystem with Vulkan, and how to do it. Richard S. Wright Jr., LunarG June 3, 2021 If you are reading this, you likely already know what Vulkan is -- a low-overhead, high-performance, cross-platform, graphics and compute API designed to take maximum advantage of today's highly parallel and scalable graphics and compute hardware. To be sure, there are other APIs with this goal such as Microsoft’s DirectX and Apple’s Metal API. For a long time OpenGL matured to meet the needs of rapidly evolving hardware and met well the challenges of cross-platform development of high-performance graphics applications. OpenGL will remain viable for a very long time for many applications (and can actually be layered on top of Vulkan), but to take maximum advantage of modern hardware, a new and somewhat reinvented approach is called for. Everyone does not need the level of control that Vulkan provides, but if you do, you can think of Vulkan as a lower-level successor to OpenGL in that it attempts to enable highly portable, yet high-performance, application development across desktop and mobile device platforms. Writing platform specific code does have its advantages, and vendors such as Microsoft and Apple certainly adore having best of breed titles available exclusively for their customers as it adds value to their ecosystem. For developers though, it is often in our best interests to make our products available as widely as possible. Aside from gaming consoles with their mostly closed development environments, Windows, Linux, Apple, and Android combined represent most of the market for developers of end user software and games today. -

Gender Inequality in Metal Music Production Emerald Studies in Metal Music and Culture

GENDER INEQUALITY IN METAL MUSIC PRODUCTION EMERALD STUDIES IN METAL MUSIC AND CULTURE Series Editors: Rosemary Lucy Hill and Keith Kahn-Harris International Editorial Advisory Board: Andy R. Brown, Bath Spa Univer- sity, UK; Amber Clifford-Napleone, University of Central Missouri, USA; Kevin Fellezs, Columbia University, USA; Cynthia Grund, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark; Gérôme Guibert, Université Sorbonne Nou- velle, France; Catherine Hoad, Macquarie University, Australia; Rosemary Overell, Otago University, New Zealand; Niall Scott, University of Central Lancashire, UK; Karl Spracklen, Leeds Beckett University, UK; Heather Savigny, De Montford University, UK; Nelson Varas-Diaz, Florida Interna- tional University, USA; Deena Weinstein, DePaul University, USA Metal Music Studies has grown enormously in recent years from a handful of scholars within Sociology and Popular Music Studies, to hundreds of active scholars working across a diverse range of disciplines. The rise of interest in heavy metal academically reflects the growth of the genre as a normal or contested part of everyday lives around the globe. The aim of this series is to provide a home and focus for the growing number of mono- graphs and edited collections that analyse heavy metal and other heavy music; to publish work that fits within the emergent subject field of metal music studies, that is, work that is critical and inter-disciplinary across the social sciences and humanities; to publish work that is of interest to and enhances wider disciplines and subject fields across social sciences and the humanities; and to support the development of early career research- ers through providing opportunities to convert their doctoral theses into research monographs. -

LG V60 Thinq 5G

ENGLISH USER GUIDE LM-V600VM OS: Android™ 11 Copyright ©2021 LG Electronics Inc. All rights reserved. MFL71797801 (1.0) www.lg.com Important Customer Information 1 Before you begin using your new phone Included in the box with your phone are separate information leaflets. These leaflets provide you with important information regarding your new device. Please read all of the information provided. This information will help you to get the most out of your phone, reduce the risk of injury, avoid damage to your device, and make you aware of legal regulations regarding the use of this device. It’s important to review the Product Safety and Warranty Information guide before you begin using your new phone. Please follow all of the product safety and operating instructions and retain them for future reference. Observe all warnings to reduce the risk of injury, damage, and legal liabilities. 2 Table of Contents Important Customer Information...............................................1 Table of Contents .......................................................................2 Feature Highlight ........................................................................5 Camera features ................................................................................................... 5 Audio recording features ....................................................................................10 LG Pay ..................................................................................................................12 Google Assistant .................................................................................................14 -

Graphics and Games #WWDC16

Graphics and Games #WWDC16 What’s New in Metal Part 2 Session 605 Charles Brissart GPU Software Engineer Dan Omachi GPU Software Engineer Anna Tikhonova GPU Software Engineer © 2016 Apple Inc. All rights reserved. Redistribution or public display not permitted without written permission from Apple. Metal at WWDC This Year A look at the sessions Adopting Metal Part One Part Two • Fundamental Concepts • Dynamic Data Management • Basic Drawing • CPU-GPU Synchronization • Lighting and Texturing • Multithreaded Encoding Metal at WWDC This Year A look at the sessions What’s New in Metal Part One Part Two • Tessellation • Function Specialization and Function • Resource Heaps and Memoryless Resource Read-Writes Render Targets • Wide Color and Texture Assets • Improved Tools • Additions to Metal Performance Shaders Metal at WWDC This Year A look at the sessions Advanced Shader Optimization • Shader Performance Fundamentals • Tuning Shader Code What’s New in Metal What’s New in Metal Tessellation Resource Heaps and Memoryless Render Targets Improved Tools What’s New in Metal Tessellation Resource Heaps and Memoryless Render Targets Improved Tools Function Specialization and Function Resource Read-Writes Wide Color and Texture Assets Additions to Metal Performance Shaders Function Specialization Charles Brissart GPU Software Engineer Function Specialization Typical pattern • Write a few complex master functions • Generate many specialized functions Function Specialization Typical pattern • Write a few complex master functions • Generate many specialized