Slum Profiles | Dagoretti Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formation, Survival and Performance of Self-Help Groups in Dagoretti South Constituency Nairobi County

FORMATION, SURVIVAL AND PERFORMANCE OF SELF-HELP GROUPS IN DAGORETTI SOUTH CONSTITUENCY NAIROBI COUNTY BY GATHUA JANET NYAMBURA T50/82237/2015 A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER, 2020 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI Declaration of Originality Form This form must be completed and signed for all works submitted to the University for Examination. Name of Student ____JANET GATHUA NAMBURA Registration Number _________T50/82237/2015_____________________________ College __COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES__________ Faculty/School/Institute_ INSTITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES_______ Department ______________________________________________________ Course Name _MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES__________ Title of the work FORMATION, SURVIVAL AND PERFORMANCE OF SELF- HELP GROUPS IN DAGORETTI SOUTH CONSTITUENCY NAIROBI COUNTY__ DECLARATION 1. I understand what Plagiarism is and I am aware of the University’s policy in this regard 2. I declare that this __________________ (Thesis, project, essay, assignment, paper, report, etc.) is my original work and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination, award of a degree or publication. Where other people’s work or my own work has been used, this has properly been acknowledged and referenced in accordance with the University of Nairobi’s requirements. 3. I have not sought or used the services of any professional agencies to produce this work 4. I have not allowed, and shall not allow anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his/her own work 5. I understand that any false claim in respect of this work shall result in disciplinary action, in accordance with University Plagiarism Policy. -

Examining the Influence of Multiple Boundary Spanning Agents on Slum Upgrading Outcomes: Studying Muungano Wa Wanavijiji Huruma Settlement Upgrading Project

MSc Program in Urban Management and Development Rotterdam, The Netherlands September 2017 Thesis Title: Examining the influence of multiple boundary spanning agents on slum upgrading outcomes: Studying Muungano Wa Wanavijiji Huruma settlement upgrading project. Name: Supervisor: Ingmar Van Meerkerk Specialization: Urban Housing and Livelihoods UMD 13 MASTER’S PROGRAMME IN URBAN MANAGEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT (October 2016 – September 2017) Examining the influence of multiple boundary spanning agents on slum upgrading outcomes: Studying Muungano Wa Wanavijiji Huruma settlement upgrading project. Anne Waithira Kamweru Kenya Supervisor: Ingmar Van Meerkerk UMD 13 Report number: 1054 Rotterdam, September 2017 Examining the influence of multiple boundary spanning agents on slum upgrading outcomes: Studying Muungano Wa ii Wanavijiji Huruma settlement upgrading project. Summary Adequate housing is a chronic headache for most of Kenyans and more so the urban poor. Both the private sector and the government acting singularly have been unable to address this problem satisfactorily and provide sufficient and adequate housing stock for all socio-economic groups. This was the basis for the formation of Slum Dwellers Federation Muungano Wa Wanavijiji a vehicle with which the urban poor communally sought solutions to their shared housing problems. One of the redressal solutions pursued by Muungano Federation for its members is the bottom-up approach of ‘community-led settlement improvement’ in Huruma. Realization of such a settlement upgrading is by no means an easy feat considering the community limitations in resources, ability to negotiate for required support from external partners and organizations, the gaping diversities in needs and interests among the community members as well as the hardship in aligning their community interests with the environment other intervening factors arising from the political and policy dynamics in Kenya. -

Organizations Offering Services for Orphaned and Vulnerable Children

ORGANIZATIONS OFFERING SERVICES FOR ORPHANED AND VULNERABLE CHILDREN Cheryl’s Children’s Home Dagoretti Corner P. O. Box 46605- 00100 Nairobi Tel: 020-2679162, 0733-987712 Feed the children, Dagoretti Kikuyu/Ndonyo Junction, Dagoretti P. O Box 61530- 00200, Nairobi Tel: 020-2124829 Cell: 0722-202958/9, 0733-202958/9 Flomina Masimba, Kayole Cell: 0722-990260 Imani Children’s Home Soweto Cell: 0726-677329 Kabete Children’s Home (Salvation Army) Lavington, Kabarsiran Avenue Cell: 0733-673798 Kabete Children’s Home(Salvation Army) Upper Kabarsiran Avenue Cell: 0733-673798 Kenya Christian Homes ( Thomas Barnardo House) Thomas Barnardo House, Langata Road Tel: 020-601922, 602002 Kicoshep Next to Chief’s Camp, Wilson Airport Tel: 020-601881 Kwetu Home of Peace Madaraka Estate, Ole Shangara Road, Opposite Strathmore University Tel: 020-604570 Cell; 0727-522152 Lea Toto-Dandora Kariobangi South (red bricks flats) along Mahutini road Tel: 020-2018802 Lea Toto-Kangemi Past Mountain View, Waiyaki Way (from town centre), opposite Baraka Petrol Station Tel. 020-2018803 Lea Toto- Kariobangi 1st floor (next to Approtec Kickstart) Landmark Plaza Building, Kamunde Road off Outering Road Tel: 020-2018805 Lea Toto- Kawangware Dagoretti, Naivasha Road, adjacent to the DC’s Office Tel: 020-2044623 Lea Toto-Kibera Olympic Estate, Next to Olympic Primary school Tel: 020-2018804 Lea Toto-Mukuru Reuben Centre, Mukuru kwa Reuben Enterprise Road (Hillocks) at Kobil Station Tel: 020-2397171 Mama Fatuma Children’s Home 1st Avenue/2nd street, Eastleigh Opposite St. Teresa Catholic Church P.O.Box 4403-00100, Nairobi Tel: 020-6764735 Fax: 020-6766335 Cell: 0722-660047 [email protected] Mama Ngina Children’s Home Next to the Mosque, South C. -

Second County Assembly – Second Session

NAIROBI CITY COUNTY ASSEMBLY OFFICIAL REPORT Second County Assembly – Second Session Wednesday 28th February, 2018 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [Hon. Speaker (Ms. Beatrice Elachi) in the Chair]] PRAYERS COMMUNICATION FROM THE CHAIR VISITING DELEGATION FROM MANDERA COUNTY ASSEMBLY Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, our sitting this afternoon is graced by Mandera County Assembly Service Board and Welfare Committee [members]. (Applause) Hon. Members, I wish to recognize the presence of; 1. The Hon. Saad Sheikh 2. The Hon. Abdinoor Teno 3. The Hon. Dakane Rafat 4. The Hon. Fatuma Omar Kasai 5. The Hon. Adan Maalim Abdullahi 6. The Hon. Noor Mohamud 7. The Hon. Mohamed Tobow 8. Mr. Ali Mohamed Ibrahim, Board Member 9. Ms. Fatuma Ibrahim, Board Member 10. Mr. Ahmed Surow, Clerk Disclaimer: The electronic version of the Official Hansard Report is for information purposes only. A certified version of this Report can be obtained from the Hansard Editor. Page 2 of 17 NAIROBI CITY COUNTY ASSEMBLY Wednesday, February 28, 2018 (Applause) I warmly welcome you to the Nairobi City County Assembly. I hope you have enjoyed your stay in the City during your auspicious visit. Hon. Members, on behalf of the Nairobi City County Assembly family, I wish to extend a warm welcome to the Hon. Members of the Mandera County Assembly Service Board and Welfare Committee. Feel welcome and enjoy your experience in Nairobi. Thank you. Yes, Hon. Robert Mbatia Hon. Robert Mbatia: Thank you, Madam Speaker. I just noticed there is another Hon. Member from Mandera in the gallery who has not been recognized. -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Party Politics and City Governance in Nairobi

PARTY POLITICS AND GOVERNANCE IN NAIROBI Samuel O. Owuor1 Paper Presented at the GDRI Governing Cities in Africa Conference Stellenbosch University, 30 November – 2 December 2009 Introduction Nairobi is probably one of the largest and best-known cosmopolitan African capital cities. Nairobi was first established in 1899 as a transportation and administrative centre, which later grew to become the capital of Kenya and a city. It is by far the smallest administrative province in Kenya, but also the most important in terms of employment, socio-economic activities and functions it performs. Apart from being the capital city of Kenya, it is the largest urban centre in the country, a regional hub in East and Central Africa, as well as the headquarters for many international and regional organizations.2 The present administrative boundary covers an area of 686 km2 expanding from 3.84 km2 in 1910. According to the 1999 Kenyan population census, Nairobi had 2,143,254 inhabitants representing about 38% of the total urban population in Kenya, with an annual growth rate of 4.8% (Bocquier et al 2009). The population of Nairobi is currently estimated to be 3.36 million inhabitants (UN- HABITAT 2008). Being a capital city, Nairobi will continue to influence the country, especially its immediate catchment areas and districts. Specifically affected are Athi River, Ongata Rongai, Ngong, Ruiru, Thika, Limuru, Kiambu, Kitengela and Kiserian, which are today functionally part of Nairobi city and add 20% more to the province’s population (Bocquier et al 2009). Given the importance of Nairobi, sustainable and inclusive city governance is a key component in its future growth and development. -

County Integrated Development Plan (Cidp) 2018-2022

COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN (CIDP) 2018-2022 WORKING DRAFT NOVEMBER, 2017 Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page ii COUNTY VISION AND MISSION VISION “The city of choice to Invest, Work and live in” MISSION To provide affordable, accessible and sustainable quality service, enhancing community participation and creating a secure climate for political, social and economic development through the commitment of a motivated and dedicated team. Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iii Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page iv FOREWORD Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page v Nairobi County Integrated Development Plan, 2018 Page vi TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTY VISION AND MISSION ............................................................................................. iii FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ......................................................................................................... xiii LIST OF PLATES ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .................................................................................... xiv GLOSSARY OF COMMONLY USED TERMS ..................................................................... -

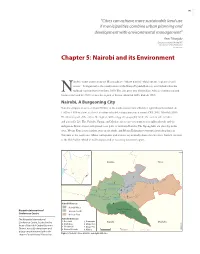

Chapter 5: Nairobi and Its Environment

145 “Cities can achieve more sustainable land use if municipalities combine urban planning and development with environmental management” -Ann Tibaijuki Executive Director UN-HABITAT Director General UNON 2007 (Tibaijuki 2007) Chapter 5: Nairobi and its Environment airobi’s name comes from the Maasai phrase “enkare nairobi” which means “a place of cool waters”. It originated as the headquarters of the Kenya Uganda Railway, established when the Nrailhead reached Nairobi in June 1899. The city grew into British East Africa’s commercial and business hub and by 1907 became the capital of Kenya (Mitullah 2003, Rakodi 1997). Nairobi, A Burgeoning City Nairobi occupies an area of about 700 km2 at the south-eastern end of Kenya’s agricultural heartland. At 1 600 to 1 850 m above sea level, it enjoys tolerable temperatures year round (CBS 2001, Mitullah 2003). The western part of the city is the highest, with a rugged topography, while the eastern side is lower and generally fl at. The Nairobi, Ngong, and Mathare rivers traverse numerous neighbourhoods and the indigenous Karura forest still spreads over parts of northern Nairobi. The Ngong hills are close by in the west, Mount Kenya rises further away in the north, and Mount Kilimanjaro emerges from the plains in Tanzania to the south-east. Minor earthquakes and tremors occasionally shake the city since Nairobi sits next to the Rift Valley, which is still being created as tectonic plates move apart. ¯ ,JBNCV 5IJLB /BJSPCJ3JWFS .BUIBSF3JWFS /BJSPCJ3JWFS /BJSPCJ /HPOH3JWFS .PUPJOF3JWFS %BN /BJSPCJ%JTUSJDUT /BJSPCJ8FTU Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ/BUJPOBM /BJSPCJ/PSUI 1BSL Conference Centre /BJSPCJ&BTU The Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ%JWJTJPOT Conference Centre, located in the ,BTBSBOJ 1VNXBOJ ,BKJBEP .BDIBLPT &NCBLBTJ .BLBEBSB heart of Nairobi's Central Business 8FTUMBOET %BHPSFUUJ 0510 District, has a 33-story tower and KNBS 2008 $FOUSBM/BJSPCJ ,JCFSB Kilometres a large amphitheater built in the Figure 1: Nairobi’s three districts and eight divisions shape of a traditional African hut. -

Global Migration Perspectives

GLOBAL MIGRATION PERSPECTIVES No. 47 September 2005 Formalizing the informal economy: Somali refugee and migrant trade networks in Nairobi Elizabeth H Campbell Binghamton University State University of New York [email protected] Global Commission on International Migration 1, Rue Richard Wagner CH:1202 Geneva Switzerland Phone: +41:22:748:48:50 E:mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.gcim.org Global Commission on International Migration In his report on the ‘Strengthening of the United Nations - an agenda for further change’, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan identified migration as a priority issue for the international community. Wishing to provide the framework for the formulation of a coherent, comprehensive and global response to migration issues, and acting on the encouragement of the UN Secretary-General, Sweden and Switzerland, together with the governments of Brazil, Morocco, and the Philippines, decided to establish a Global Commission on International Migration (GCIM). Many additional countries subsequently supported this initiative and an open-ended Core Group of Governments established itself to support and follow the work of the Commission. The Global Commission on International Migration was launched by the United Nations Secretary-General and a number of governments on December 9, 2003 in Geneva. It is comprised of 19 Commissioners. The mandate of the Commission is to place the issue of international migration on the global policy agenda, to analyze gaps in current approaches to migration, to examine the inter-linkages between migration and other global issues, and to present appropriate recommendations to the Secretary-General and other stakeholders. The research paper series 'Global Migration Perspectives' is published by the GCIM Secretariat, and is intended to contribute to the current discourse on issues related to international migration. -

Kenya Office

JICA2016 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ANNUAL REPORT KENYA OFFICE TICAD VI and BEYOND TICAD VI and BEYOND Photo by Takeshi Kuno Takeshi by Photo A historic event - TICAD VI held in Nairobi in August 2016 Cover photos (clockwise): · Improvement of quality of health service through mentorship · ABE Initiative Participant Harrison Odhiambo explains his research at the Dandora dumpsite to JICA and Nairobi County staff · Rusumo One Stop Border Post (OSBP) supported by JICA – Rwanda/Tanzania border · Engineers at the Kenya Electricity Generating Company (KenGen) · Charles Mureithi, training ex-participant who won second place in the National Farmers Award, 2016 · JICA Senior Volunteer teaches students about farm machinery Contents 2 Message from Chief Representative 30 PILLAR 2: Promoting Resilient Health Systems for Quality of Life 3 SDGs and JICA’s Key Sectors 36 PILLAR 3: Promoting Social Stability for 3 Figures of JICA Kenya Activities Shared Prosperity 4 Highlights in 2016 41 JICA’S Projects 6 TICAD VI Summit 47 Location of JICA’S Projects 14 PILLAR 1: Promoting Structural 48 Acronyms Economic Transformation through Economic Diversification and Industrialisation About Us: The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Inclusive and Dynamic Our Development Vision l Addressing the Global Agenda l Reducing Poverty Through Our Equitable Growth Mission l Improving Governance l Achieving Human Security JICA KENYA 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 1 t is my pleasure to share with you JICA Kenya Office’s activities and achievements in 2016 through this Annual report whose theme is “TICAD VI and BEYOND”. IIn August, 2016, we all in Nairobi saw with our own eyes the remarkable success of TICAD VI - the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development- as the very first TICAD held on the African soil and a manifestation of African ownership of its development process. -

KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya

KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic Of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) CIX—No. 16 NAIROBI, 23rd February, 2007 Price Sh. 50 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES—(contd.) PAGE PAGE The Children Act—Appointment 340' The Companies Act-Fourth Dividend to Depositors - and Creditors • 386. The Income Tax Act—Appointment 340 The National Assembly and Presidential Elections The Kenya ,Communications Act--Apixnntment, etc 340.387- Act—Appointment of Registration and Assistant • Registration Officers—Corrigenda 387 Task Force on the Reivie*.and.Flarrnottization of the Legal Framework Governing the Education The Kenya Power and Lighting Company SectorExtension of Period of Appointment 340 Limited—Foreign Exchange Fluctuation Adjustment, etc 387-388 The EnvirOnmental Management and Co-ordination ,, Act—Appniiiintent: etc 340-342 Transfer of Business 388 Pag Mvogal0,4q-'APP9inlinent 342 Loss of Policies 389 'The' . Magistrates" Ctiuns Art Increase Or Limit of Change of Name 389 ..1.0risdiction 342 The Police Act—Declarations 342-343 The Prisons Act—Appointment 343 The Registration of. Titles Act—Issue of Provisional SUPPLEMENT No. 9 343 Certificates. etc Legislatim Supplement The Registered LAO, Act-71..sxue ,of New Land Title LEGAL NOTICE NO. PAGE Deeds. etc 343-349 Maritime Authority Land Acquisition Ai.1.-.4titention'to Acquire Land. etc 349-350 22-,The Kenya Act—Commencernent 44 Probate and Administration 350-380 23—The Traffic Act—Revocation The Civil Aviation Act—Decisions on Applications for Local - Government (Electoral Areas) Air Service Licences 380-382 24—The (Amendment) Order, 2007 45 The • Medical PraetitiOnerS and Dentists Act—Approved Institutions 382-385 The Phy.ical Planning Act—Completion of frail Development Plans •385-386 SUPPLEMENT No. -

Nairobi Matatu Routes Thika Town

GITHUNGURI KIAMBU ROAD NAIROBI MATATU ROUTES THIKA TOWN 237 120 Route Outbound Inbound BOMA ROAD 36 From City Center 33 To City Center 48B 116 LIMURU Stop Terminus City Center Junction RUIRU TOWN Kiambu Komarocks Westlands Yaya 145D 100/100A 19C 48 Jacaranda Githunguri Lavington 145B 145 34B 48A 120 Kayole KAYOLE Valley Arcade BYPASS Ndumberi 1960 LIMURU ROAD Kayole 48B/O KIAMBU ROAD KIAMBU RD. 121 Yaya NDUMBERI Clayworks Mwiki KILELESHWA 1961C 120 BANANA TERMINUS 107D Caltex Kayole 48C 17B Kangemi 121 KIAMBU KENYATTA Baba Ndogo 1961CK GOLF UNIVERSITY Pipeline Jogoo 22/23 25 Uthiru Lucky Summer 33PJ THIKA RD. THIKA 30 106 Pipeline Mombasa Kikuyu KENYATTA 25A 116 M COFFEE UNIVERSITY Kariobangi 33PM KIAMBU JKIA 105 ESTATE Limuru 27 WAY WAIYAKI Kahawa EMBAKASI 34J Sukari Mathare N 114W/115/135 135 Lunga Lunga 237 29/30 Wangige 115 WINDSOR Ngumba 70/71 GOLF KAHAWA WEST 145 South C 118 Wangige 114W RUAKA Kahawa KARURA 45K 43 Wendani KU 12C KPA 119 44Z 107 44G/Z Gathiga ELDORET-MALABA RD Thindigwa 12D 44K Roysambu KU Fedha Estate 119A Highridge 44G 44K 33B/FED Githurai 11A GITHURAI Ruai Bypass RD. PARKLANDS KWAHERI MARURUI Ruaka NORTHERN BYPASS RD. MOMBASA 45G 33H 107D KU Utawala 11F WANGIGE 44 Banana PROGGIE 45K 33UTW USUI LIMURU ROAD 121 45P Githurai Proggie Athiriver 106 Car Wash Ndenderu 45P 110ATH 120 Sunton Kitengela 107 118 GATHIGA Runda KING’EERO GICHAGI LIMURU RD. UN Gichagi Roysambu Footbridge 110KIT 100A 49 Strathmore 103 129 EASTERN BYPASS Ruiru Town 108 Kasarani Corner Stone Limuru Police Naivas Academy 100 14A 145 Deep West 108 116 Ridgeways 53 Ruiru Town Torrents (Loop) Karen Dagoretti Village Market ROYSAMBU/ 14B Safari Park Seasons GETATHURU ROAD 119A 145D Langata 237 KASARANI 17B 1 REDHILL Thika Town Rikana Joster 145 15 Garden City / 49 237 Highrise 119 Homeland Eastleigh RD.