Constitution Making in Zambia by Melvin Mbao

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delayed Govt Support to Farmers Angers Members of Parliament PF

No 65 www.diggers.news Friday November 24, 2017 Delayed govt support to farmers Eric Chanda angers members of parliament joins NDC By Zondiwe Mbewe And a Choma district farmer, I have joined NDC because I have seen Sata’s pro-poor Joseph Sichoza, says Siliya is policies in Chishimba Kambwili and the NDC, says Eric fooling farmers by promising Chanda. that one million beneficiaries Chanda has since told News Diggers! that he is no longer will receive e-voucher cards president of the 4th Revolution. by next week, saying such an “I’m a member of the central committee of the National undertaking was impossible Democratic Congress with a position. But let me not confirm and would be a miracle to it now, I will confirm at a later stage. I will be holding a press achieve. conference at some appropriate time . But what I can confirm During the questions for oral for now is that I’m an NDC member," Chanda said. answer session in Parliament "For now, ifyabu president nafipwa. For now, I’m no longer MPS today, Katuba UPND member a president [of the 4th Revolution]. All of us must live to of parliament Patricia support the cause of NDC to put a stop to the Edgar Lungu- led corrupt government." Mwashingwele asked Siliya By Mirriam Chabala And Chanda has already started fighting battles for the newly to explain why she had gone Agriculture minister Dora formed party, while encouraging citizens to join-in. back to Parliament for the Siliya this morning struggled On Wednesday, PF Copperbelt youth chairman Nathan second time to give farmers to explain why government Chanda who is also Luanshya mayor said Kambwili was a deadline for the activation has been making empty practicing childish politics because he kept insulting of e-voucher cards which she promises over the distribution President Lungu; a statement that did not go well with knew would not even be met. -

Zambia Page 1 of 8

Zambia Page 1 of 8 Zambia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Zambia is a republic governed by a president and a unicameral national assembly. Since 1991, multiparty elections have resulted in the victory of the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD). MMD candidate Levy Mwanawasa was elected President in 2001, and the MMD won 69 out of 150 elected seats in the National Assembly. Domestic and international observer groups noted general transparency during the voting; however, they criticized several irregularities. Opposition parties challenged the election results in court, and court proceedings were ongoing at year's end. The anti-corruption campaign launched in 2002 continued during the year and resulted in the removal of Vice President Kavindele and the arrest of former President Chiluba and many of his supporters. The Constitution mandates an independent judiciary, and the Government generally respected this provision; however, the judicial system was hampered by lack of resources, inefficiency, and reports of possible corruption. The police, divided into regular and paramilitary units under the Ministry of Home Affairs, have primary responsibility for maintaining law and order. The Zambia Security and Intelligence Service (ZSIS), under the Office of the President, is responsible for intelligence and internal security. Civilian authorities maintained effective control of the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous serious human rights abuses. Approximately 60 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, although agriculture contributed only 15 percent to the gross domestic product. Economic growth increased to 4 percent for the year. -

Theparliamentarian

100th year of publishing TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2019 | Volume 100 | Issue Two | Price £14 The Commonwealth at 70: PAGES 126-143 ‘A Connected Commonwealth’ PLUS Commonwealth Day Political and Procedural Effective Financial The Scottish Parliament 2019 activities and Challenges of a Post- Oversight in celebrates its 20th events Conflict Parliament Commonwealth anniversary Parliaments PAGES 118-125 PAGE 146 PAGE 150 PAGE 152 64th COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE KAMPALA, UGANDA 22 to 29 SEPTEMBER 2019 (inclusive of arrival and departure dates) For further information visit www.cpc2019.org and www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpc2019 CONFERENCE THEME: ‘ADAPTATION, ENGAGEMENT AND EVOLUTION OF PARLIAMENTS IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING COMMONWEALTH’. Ū One of the largest annual gatherings of Commonwealth Parliamentarians. Hosted by the CPA Uganda Branch and the Parliament of Uganda. Ū Over 500 Parliamentarians, parliamentary staff and decision makers from across the Commonwealth for this unique conference and networking opportunity. Ū CPA’s global membership addressing the critical issues facing today’s modern Parliaments and Legislatures. Ū Benefit from professional development, supportive learning and the sharing of best practice with colleagues from Commonwealth Parliaments together with the participation of leading international organisations. During the 64th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, there will also be a number of additional conferences and meetings including: 37th CPA Small Branches Conference; 6th triennial Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Conference; 64th CPA General Assembly; meetings of the CPA Executive Committee; and the Society of Clerks at the Table (SOCATT) meetings. This year, the conference will hold elections for the Chairperson of the Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP), the CPA Treasurer and the CPA Small Branches Chairperson for new three-year terms. -

Intra-Party Democracy in the Zambian Polity1

John Bwalya, Owen B. Sichone: REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY … REFRACTORY FRONTIER: INTRA-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN THE ZAMBIAN POLITY1 John Bwalya Owen B. Sichone Abstract: Despite the important role that intra-party democracy plays in democratic consolidation, particularly in third-wave democracies, it has not received as much attention as inter-party democracy. Based on the Zambian polity, this article uses the concept of selectocracy to explain why, to a large extent, intra-party democracy has remained a refractory frontier. Two traits of intra-party democracy are examined: leadership transitions at party president-level and the selection of political party members for key leadership positions. The present study of four political parties: United National Independence Party (UNIP), Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), United Party for National Development (UPND) and Patriotic Front (PF) demonstrates that the iron law of oligarchy predominates leadership transitions and selection. Within this milieu, intertwined but fluid factors, inimical to democratic consolidation but underpinning selectocracy, are explained. Keywords: Intra-party Democracy, Leadership Transition, Ethnicity, Selectocracy, Third Wave Democracies Introduction Although there is a general consensus that political parties are essential to liberal democracy (Teorell 1999; Matlosa 2007; Randall 2007; Omotola 2010; Ennser-Jedenastik and Müller 2015), they often failed to live up to the expected democratic values such as sustaining intra-party democracy (Rakner and Svasånd 2013). As a result, some scholars have noted that parties may therefore not necessarily be good for democratic consolidation because they promote private economic interests, which are inimical to democracy and state building (Aaron 1 The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments from the editorial staff and anonymous reviewers. -

CHAPTER 1 the SYSTEM of LAND ALIENATION Introduction Zambia Is

CHAPTER 1 THE SYSTEM OF LAND ALIENATION Introduction Zambia is a landlocked country located in Southern Africa. It covers an area of about 752,614 square kilometres between latitudes 8 and 18 degrees South, and the longitudes 22 and 23 degrees East. A large part of the country is on the Central African plateau between 1000 meters, and 1600 meters above sea level. The system of land tenure in Zambia is based on statutory and customary law. Statutory law comprises rules and regulations which are written down, and codified. Customary law, on the other hand, is not written, but it is assumed that the rules and regulations under this system are well known to members of the community. Statutory law is premised on the English land tenure system, while customary tenure is essentially based on tribal law. Land in Zambia is administered through various statutes by established institutions in the country. 1 Land administration in general is a way and means by which land alienation and utilisation are managed. The process of land administration therefore, includes the regulating of land and property development, the use and conservation of the land, the gathering of revenue from the land through ground rent, consideration fees, survey fees, and registration fees; and the resolving of conflicts concerning the ownership and use of the land. 1 Functions of land administration may be divided into four components, namely: juridical, regulatory, fiscal and information management. 2 The juridical aspect places greatest emphasis on the acquisition and registration of rights in land. It comprises a series of processes concerned with the allocation of land through original grants from the President. -

Zambia's 2001 Elections: the Tyranny of Small Decisions, 'Non-Decisions

Third World Quarterly, Vol 23, No 6, pp 1103–1120, 2002 Zambia’s 2001 elections: the tyranny of small decisions, ‘non-decisions’ and ‘not decisions’ PETER BURNELL ABSTRACT The course of the 1990s witnessed deterioration in the quality of elections held across sub-Saharan Africa. Zambia’s elections for the presidency, parliament and local government held on 27 December 2001 are no exception. They returned the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) to power, but with much reduced popular support and leaving doubts about the legitimacy of the result. A ‘tyranny of small decisions’, ‘non-decisions’ and ‘not decisions’ perpetrated over 12 months or more leading up to these elections combined to influence the outcome. The previous MMD government and the formally autono- mous Electoral Commission were primarily but not wholly responsible. For independent analysts as well as for the political opposition, who secured a majority of parliamentary seats while narrowly failing to capture the presidency, identifying the relevant category of ‘decisions’ to which influences belong and comparing their impact is no straightforward matter. Zambia both illustrates the claim that ‘administrative problems are typically the basis of the flawed elections’ in new democracies and refines it by showing the difficulty of clearly separating the administrative and political factors. In contrast Zimbabwe’s presi- dential election in March 2002, which had the Zambian experience to learn from, appears a more clear-cut case of deliberate political mischief by the ruling party. There is little doubt that in the course of the 1990s the quality of Africa’s elections went into decline. -

Observing the 2001 Zambia Elections

SPECIAL REPORT SERIES THE CARTER CENTER WAGING PEACE ◆ FIGHTING DISEASE ◆ BUILDING HOPE OBSERVING THE 2001 ZAMBIA ELECTIONS THE CARTER CENTER STRIVES TO RELIEVE SUFFERING BY ADVANCING PEACE AND HEALTH WORLDWIDE; IT SEEKS TO PREVENT AND RESOLVE CONFLICTS, ENHANCE FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY, AND PROTECT AND PROMOTE HUMAN RIGHTS WORLDWIDE. THE CARTER CENTER NDINDI OBSERVING THE 2001 ZAMBIA ELECTIONS OBSERVING THE 2001 ZAMBIA ELECTIONS FINAL REPORT THE CARTER CENTER The Democracy Program One Copenhill Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 FAX (404) 420-5196 WWW.CARTERCENTER.ORG OCTOBER 2002 1 THE CARTER CENTER NDI OBSERVING THE 2001 ZAMBIA ELECTIONS 2 THE CARTER CENTER NDINDI OBSERVING THE 2001 ZAMBIA ELECTIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Carter Center Election Observation Delegation and Staff ............................................................... 5 Terms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. 7 Foreword ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 10 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................. 15 Background ...................................................................................................................................... -

Members of the Northern Rhodesia Legislative Council and National Assembly of Zambia, 1924-2021

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA Parliament Buildings P.O Box 31299 Lusaka www.parliament.gov.zm MEMBERS OF THE NORTHERN RHODESIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL AND NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA, 1924-2021 FIRST EDITION, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 3 PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 5 ABBREVIATIONS ...................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 9 PART A: MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1924 - 1964 ............................................... 10 PRIME MINISTERS OF THE FEDERATION OF RHODESIA .......................................................... 12 GOVERNORS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA AND PRESIDING OFFICERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) ............................................................................................... 13 SPEAKERS OF THE LEGISTRATIVE COUNCIL (LEGICO) - 1948 TO 1964 ................................. 16 DEPUTY SPEAKERS OF THE LEGICO 1948 TO 1964 .................................................................... -

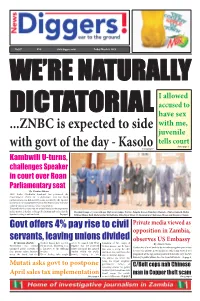

ZNBC Is Expected to Side with Govt of The

No387 K10 www.diggers.news Friday March 8, 2019 WE’RE NATURALLY I allowed accused to DICTATORIAL have sex with me, ...ZNBC is expected to side juvenile tells court Story page 3 with govt of the day - KasoloStory page 7 Kambwili U-turns, challenges Speaker in court over Roan Parliamentary seat By Zondiwe Mbewe NDC leader Chishimba Kambwili has petitioned the Constitutional Court for a declaration that his Roan parliamentary seat did not fall vacant as ruled by the Speaker of the National Assembly Dr Patrick Matibini because the latter violated various provisions of the Constitution. Kambwili who has cited the Attorney General as the respondent in this matter, is further seeking a declaration and order that the President Lungu (c) poses with new High Court judges: Evaristo Pengele, Koreen Etambuyu Mwenda - Zimba, Kenneth Mulife, Speaker’s ruling is null and void. To page 5 Wilfred Muma, Ruth Hachitapika Chibbabbuka, Abha Nayar Patel, SC, Bonaventure Chakwawa Mbewe and Kazimbe Chenda. Govt offers 4% pay rise to civil Private media viewed as opposition in Zambia, servants, leaving unions divided observes US Embassy By Mirriam Chabala workers’ unions have rejected not to be named, told News formation of two camps of By Stuart Lisulo Government has offeredthe proposal, describing it as Diggers! that the proposed workers unions - one for those Zambia has a lot of work to do in embracing divergent views unionised public servants a a disservice to the suffering salary increment has spurred that want to accept the offer because the private news media are still being viewed as a four percent salary increase workers. -

Zambia Law Journal

ISSN 1027-7862 ZAMBIA LAW JOURNAL The Zambia* Constitution and tl Principles of Constitutional Autochthony and Supremacy C. Anyan< The State Security Act Vs Open Society: Does a Democracy Need Secrets? AW.Chandaida Refashioning the Legal Geography of the Quistclose Trust K. Mwenda The Criminal Process in Juvenile Courts in Zambia E. Simaluwani • 3ase Comment DJL RECENT JUDICIAL DECISIONS RECENT LEGISLATION The University of Zambia EDITORIAL BOARD General Editor Ngosa Simbyakula Chief Editor Alfred W.Chanda Associate Editor Larry N. McGill Members Patrick Matibini, John Sangwa, Amelia Pio Young Assistant Editor Christopher Bwalya, UNZA Press Notes to Contributors 1. Manuscripts should be submitted in triplicate, typed, with double spacing on one side of the page only. Contributors should also submit their complete manuscript on diskette, preferably in Microsoft Word 6.0 format. 2. Authors of manuscripts that are published in the Journal receive two copies of the Journal free of charge. 3. Manuscripts should be sent to: The Chief Editor Zambia Law Journal University of Zambia, School of Law P.O. Box 32379 Lusaka, Zambia 4. The Chief Editor can also be contacted by e-mail at: [email protected]. When possible, contributors should provide an e-mail address where they can be reached. Subscriptions Subscribers who are residents outside Zambia should send subscriptions to: Dr A. Milner Law Reports International Trinity College Oxford 1X1 3 BH England e-mail: [email protected] Published by the University of Zambia Press, P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia. Typeset and designed by the University of Zambia Press, Lusaka, Zambia. -

The Politics

AFRIG\ A Complicated War The UNESCO General The Harrowing of Mozambique WILLIAM FINNEGAN History of Africa "A sobering look at one of Africa's most devastating civil "One ot the most ambitious academic projects to wars. ...Vivid reportage, thoughtful analysis, and compre- be undertaken in this century."—West Africa hensive research; a seminal work not only on the war itself but on the conflicts that threaten post-cold-war, post- apartheid Africa."—Kirkus Revieus Volume V $25.00 doih PerslKctives on Southern Africa Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eigh- teenth Century Edited by B. A. OGOT A Democratic This fifth volume covers the history of the conti- nent as two themes emerge: the continuing inter- South Africa? nal evolution ot the states and cultures of Africa; Constitutional Engineering in and the increasing involvement of Africa in exter- a Divided Society nal trade—with consequences for the whole world. DONALD L. HOROWITZ $45.00doth, illustrated New in paper—"A masterful analysis of the current situation in South Africa ... it makes suggestions that New Abridged Paperback Edition— might well shape the outcome of discussions in South Africa regarding the country's future." Volume III —Lcroy Vail, Harvard University Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh SJ3.00 paper Perspectives on Southern Africa Century M. EL FASI, Editor I. Hrbck, Assistant Editor "A welcome contribution to the literature about Africa an important period in African history. ... A Endurance and Change South of the Sahara stimulating and informative guide." CATHERINE COQUERY-VIDROVITCH —African Economic History Translated by David Maisel $12.00 paper, illustrated New in paper—"A first-rate study on the forces and developments that have shaped contemporary Africa." —International journal of African Historical Studies $15.00 paper Winner of the Prix d'Aurnaie of the ActuLhrie des Sciences Morales et Polhiques At hr»Jcst<nvs in- order toll-free I -800-822-6657. -

Zambia Edalina Rodrigues Sanches Zambia Became Increasingly

Zambia Edalina Rodrigues Sanches Zambia became increasingly authoritarian under Patriotic Front (PF) President Edgar Lungu, who had been elected in a tightly contested presidential election in 2016. The runner-up, the United Party for National Development (UPND), engaged in a series of actions to challenge the validity of the results. The UPND saw 48 of its legislators suspended for boycotting Lungu’s state of the nation address and its leader, Hakainde Hichilema, was arrested on charges of treason after his motorcade allegedly blocked Lungu’s convoy. Independent media and civil society organisations were under pressure. A state of emergency was declared after several arson attacks. Lungu announced his intention to run in the 2021 elections and warned judges that blocking this would plunge the country into chaos. The economy performed better, underpinned by global economic recovery and higher demand for copper, the country’s key export. Stronger performance in the agricultural and mining sectors and higher electricity generation also contributed to the recovery. The Zambian kwacha stabilised against the dollar and inflation stood within the target. The cost of living increased. The country’s high risk of debt distress led the IMF to put off a $ 1.3 bn loan deal. China continued to play a pivotal role in Zambia’s economic development trajectory. New bilateral cooperation agreements were signed with Southern African countries. Domestic Politics The controversial results of the August 2016 presidential elections heightened political tensions for most of the year. Hakainde Hichilema, the UPND presidential candidate since 2006, saw the PF incumbent Lungu win the election by a narrow margin and subsequently contested the results, alleging that the vote was rigged.