Money and Leadership: a Study of Theses on Public School Libraries Submitted to the University of the Philippines’ Institute of Library and Information Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Quezon City Public Library

HISTORY OF QUEZON CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY The Quezon City Public Library started as a small unit, a joint venture of the National Library and Quezon City government during the incumbency of the late Mayor Ponciano Bernardo and the first City Superintendent of Libraries, Atty. Felicidad Peralta by virtue of Public Law No. 1935 which provided for the “consolidation of all libraries belonging to any branch of the Philippine Government for the creation of the Philippine Library”, and for the maintenance of the same. Mayor Ponciano Bernardo 1946-1949 June 19, 1949, Republic Act No. 411 otherwise known as the Municipal Libraries Law, authored by then Senator Geronimo T. Pecson, which is an act to “provide for the establishment, operation and Maintenance of Municipal Libraries throughout the Philippines” was approved. Mrs. Felicidad A. Peralta 1948-1978 First City Librarian Side by side with the physical and economic development of Quezon City officials particularly the late Mayor Bernardo envisioned the needs of the people. Realizing that the achievements of the goals of a democratic society depends greatly on enlightened and educated citizenry, the Quezon City Public Library, was formally organized and was inaugurated on August 16, 1948, with Aurora Quezon, as a guest of Honor and who cut the ceremonial ribbon. The Library started with 4, 000 volumes of books donated by the National Library, with only four employees to serve the public. The library was housed next to the Post Office in a one-storey building near of the old City Hall in Edsa. Even at the start, this unit depended on the civic spirited members of the community who donated books, bookshelves and other reading material. -

The Conflict of Political and Economic Pressures in Philippine Economic

This dissertation has been Mic 61-2821 naicrofilmed exactly as received BRAZIL, Harold Edmund. THE CONFLICT OF POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC PRESSURES m PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Political Science, public administration University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE CONFLICT OF POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC PRESSURES IN PHILIPPINE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for tjie Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Harold Edmund Brazil, B, S., M. A» The Ohio S tate U niversity 1961 Approved by Adviser Co-Adviser Department of Political Science PREFACE The purpose of this study is to examine the National Economic Council of the Philippines as a focal point of the contemporary life of that nation. The claim is often made that the Republic of the Philippines, by reason of American tutelage, stands as the one nation in the Orient that has successfully established itself as an American-type democracy. The Philippines is confronted today by serious econcanic problems which may threaten the stability of the nation. From the point of view of purely economic considerations, Philippine national interests would seem to call for one line of policy to cope with these economic problems. Yet, time and again, the Philippine government has been forced by political considerations to foUcw some other line of policy which was patently undesirable from an economic point of view. The National Economic Council, a body of economic experts, has been organized for the purpose of form ulating economic p o licy and recommend ing what is economically most desirable for the nation. -

Proceeding 2018

PROCEEDING 2018 CO OCTOBER 13, 2018 SAT 8:00AM – 5:30PM QUEZON CITY EXPERIENCE, QUEZON MEMORIAL, Q.C. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EDITOR Ernie M. Lopez, MBA Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa, AA MANAGING EDITOR EDITORIAL BOARD Jose F. Peralta, DBA, CPA PRESIDENT, CHIEF ACADEMIC OFFICER & DEAN Antonio M. Magtalas, MBA, CPA VICE PRESIDENT FOR FINANCE & TREASURER Tabassam Raza, MAURP, DBA, Ph.D. P.E. ASSOCIATE DEAN Jose Teodorico V. Molina, LLM, DCI, CPA CHAIR, GSB AD HOC COMMITTEE EDITORIAL STAFF Ernie M. Lopez Susan S. Cruz Ramon Iñigo M. Espinosa Philip Angelo Pandan The PSBA THIRD INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH COLLOQUIUM PROCEEDINGS is an official business publication of the Graduate School of Business of the Philippine School of Business Administration – Manila. It is intended to keep the graduate students well-informed about the latest concepts and trends in business, management and general information with the goal of attaining relevance and academic excellence. PSBA Manila 3IRC Proceedings Volume III October 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Description Page Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................. i Concept Note ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Program of Activities .......................................................................................................................... 6 Resource -

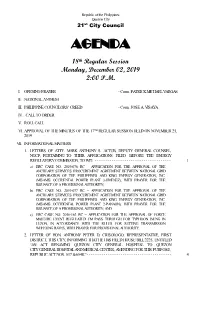

AGENDA (18Th Regular Session)

Republic of the Philippines Quezon City 21st City Council AGENDA 18th Regular Session Monday, December 02, 2019 2:00 P.M. I. OPENING PRAYER - Coun. PATRICK MICHAEL VARGAS II. NATIONAL ANTHEM III. PHILIPPINE COUNCILORS’ CREED - Coun. JOSE A. VISAYA IV. CALL TO ORDER V. ROLL CALL VI. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES OF THE 17TH REGULAR SESSION HELD ON NOVEMBER 25, 2019. VII. INFORMATIONAL MATTERS 1. LETTERS OF ATTY. MARK ANTHONY S. ACTUB, DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL, NGCP, PERTAINING TO THEIR APPLICATIONS FILED BEFORE THE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION, TO WIT: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 a) ERC CASE NO. 2019-076 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 3-JIMENEZ), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; b) ERC CASE NO. 2019-077 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF THE ANCILLARY SERVICES PROCUREMENT AGREEMENT BETWEEN NATIONAL GRID CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES AND KING ENERGY GENERATION, INC. (MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL POWER PLANT 2-PANAON), WITH PRAYER FOR THE ISSUANCE OF A PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY; AND c) ERC CASE NO. 2016-163 RC – APPLICATION FOR THE APPROVAL OF FORCE MAJEURE EVENT REGULATED FM PASS THROUGH FOR TYPHOON INENG IN LUZON, IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE RULES FOR SETTING TRANSMISSION WHEELING RATES, WITH PRAYER FOR PROVISIONAL AUTHORITY. 2. LETTER OF HON. ANTHONY PETER D. CRISOLOGO, REPRESENTATIVE, FIRST DISTRICT, THIS CITY, INFORMING THAT HE HAS FILED HOUSE BILL 2225, ENTITLED “AN ACT RENAMING QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL TO QUEZON CITY GENERAL HOSPITAL AND MEDICAL CENTER, AMENDING FOR THIS PURPOSE, REPUBLIC ACT NOS. -

Masterlist of Private Schools Sy 2011-2012

Legend: P - Preschool E - Elementary S - Secondary MASTERLIST OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 MANILA A D D R E S S LEVEL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL HEAD POSITION TELEPHONE NO. No. / Street Barangay Municipality / City PES 1 4th Watch Maranatha Christian Academy 1700 Ibarra St., cor. Makiling St., Sampaloc 492 Manila Dr. Leticia S. Ferriol Directress 732-40-98 PES 2 Adamson University 900 San Marcelino St., Ermita 660 Manila Dr. Luvimi L. Casihan, Ph.D Principal 524-20-11 loc. 108 ES 3 Aguinaldo International School 1113-1117 San Marcelino St., cor. Gonzales St., Ermita Manila Dr. Jose Paulo A. Campus Administrator 521-27-10 loc 5414 PE 4 Aim Christian Learning Center 507 F.T. Dalupan St., Sampaloc Manila Mr. Frederick M. Dechavez Administrator 736-73-29 P 5 Angels Are We Learning Center 499 Altura St., Sta. Mesa Manila Ms. Eva Aquino Dizon Directress 715-87-38 / 780-34-08 P 6 Angels Home Learning Center 2790 Juan Luna St., Gagalangin, Tondo Manila Ms. Judith M. Gonzales Administrator 255-29-30 / 256-23-10 PE 7 Angels of Hope Academy, Inc. (Angels of Hope School of Knowledge) 2339 E. Rodriguez cor. Nava Sts, Balut, Tondo Manila Mr. Jose Pablo Principal PES 8 Arellano University (Juan Sumulong campus) 2600 Legarda St., Sampaloc 410 Manila Mrs. Victoria D. Triviño Principal 734-73-71 loc. 216 PE 9 Asuncion Learning Center 1018 Asuncion St., Tondo 1 Manila Mr. Herminio C. Sy Administrator 247-28-59 PE 10 Bethel Lutheran School 2308 Almeda St., Tondo 224 Manila Ms. Thelma I. Quilala Principal 254-14-86 / 255-92-62 P 11 Blaze Montessori 2310 Crisolita Street, San Andres Manila Ms. -

CHAPTER 1: the Envisioned City of Quezon

CHAPTER 1: The Envisioned City of Quezon 1.1 THE ENVISIONED CITY OF QUEZON Quezon City was conceived in a vision of a man incomparable - the late President Manuel Luis Quezon – who dreamt of a central place that will house the country’s highest governing body and will provide low-cost and decent housing for the less privileged sector of the society. He envisioned the growth and development of a city where the common man can live with dignity “I dream of a capital city that, politically shall be the seat of the national government; aesthetically the showplace of the nation--- a place that thousands of people will come and visit as the epitome of culture and spirit of the country; socially a dignified concentration of human life, aspirations and endeavors and achievements; and economically as a productive, self-contained community.” --- President Manuel L. Quezon Equally inspired by this noble quest for a new metropolis, the National Assembly moved for the creation of this new city. The first bill was filed by Assemblyman Ramon P. Mitra with the new city proposed to be named as “Balintawak City”. The proposed name was later amended on the motion of Assemblymen Narciso Ramos and Eugenio Perez, both of Pangasinan to “Quezon City”. 1.2 THE CREATION OF QUEZON CITY On September 28, 1939 the National Assembly approved Bill No. 1206 as Commonwealth Act No. 502, otherwise known as the Charter of Quezon City. Signed by President Quezon on October 12, 1939, the law defined the boundaries of the city and gave it an area of 7,000 hectares carved out of the towns of Caloocan, San Juan, Marikina, Pasig, and Mandaluyong, all in Rizal Province. -

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published By

FILIPINOS in HISTORY Published by: NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE T.M. Kalaw St., Ermita, Manila Philippines Research and Publications Division: REGINO P. PAULAR Acting Chief CARMINDA R. AREVALO Publication Officer Cover design by: Teodoro S. Atienza First Printing, 1990 Second Printing, 1996 ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 003 — 4 (Hardbound) ISBN NO. 971 — 538 — 006 — 9 (Softbound) FILIPINOS in HIS TOR Y Volume II NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 Republic of the Philippines Department of Education, Culture and Sports NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE FIDEL V. RAMOS President Republic of the Philippines RICARDO T. GLORIA Secretary of Education, Culture and Sports SERAFIN D. QUIASON Chairman and Executive Director ONOFRE D. CORPUZ MARCELINO A. FORONDA Member Member SAMUEL K. TAN HELEN R. TUBANGUI Member Member GABRIEL S. CASAL Ex-OfficioMember EMELITA V. ALMOSARA Deputy Executive/Director III REGINO P. PAULAR AVELINA M. CASTA/CIEDA Acting Chief, Research and Chief, Historical Publications Division Education Division REYNALDO A. INOVERO NIMFA R. MARAVILLA Chief, Historic Acting Chief, Monuments and Preservation Division Heraldry Division JULIETA M. DIZON RHODORA C. INONCILLO Administrative Officer V Auditor This is the second of the volumes of Filipinos in History, a com- pilation of biographies of noted Filipinos whose lives, works, deeds and contributions to the historical development of our country have left lasting influences and inspirations to the present and future generations of Filipinos. NATIONAL HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1990 MGA ULIRANG PILIPINO TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Lianera, Mariano 1 Llorente, Julio 4 Lopez Jaena, Graciano 5 Lukban, Justo 9 Lukban, Vicente 12 Luna, Antonio 15 Luna, Juan 19 Mabini, Apolinario 23 Magbanua, Pascual 25 Magbanua, Teresa 27 Magsaysay, Ramon 29 Makabulos, Francisco S 31 Malabanan, Valerio 35 Malvar, Miguel 36 Mapa, Victorino M. -

Filipino Star July 2012 Issue

Vol. XXX, No. 7 JULY 2012 http://www.filipinostar.org It's fiesta time for Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. By W. G. Quiambao Mackenzie King park was chock-full of activities last July 15 during the FAMAS Pista sa Nayon, one of the much-anticipated events by many Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. Friends seeing friends they haven’t seen for a while, music lovers listening to Filipino songs, women playing volleyball, kids enjoying pabitin (a rack of items is suspended over a crowd who attempt to grab at the stuff as the wooden rack is lowered and raised several times until everything is gone), revellers enjoying A few games of volleyball, arranged and managed by Mercy Sia Umipig and played by all-girl teams, was part of Pista sa Nayon (Photo: B. Sarmiento) a bounty of delicious foods - these are some of the activities during Pista sa Part of Ambassador Leslie B. bond of unity in a foreign setting." Nayon in the Philippines which are also Gatan's message read, "I wish to The tradition of the Pista sa practiced in Montreal every year. extend my heartfelt and warm Nayon dates back to centuries to the “Today, we celebrate the very congratulations to the Officers and rural areas and town in the Philippines. best of being Filipino," said Au Osdon, members of the Filipino Association of During Pista sa Nayon (called town FAMAS president. "The Bayanihan Montreal & Suburbs for their festival or fiesta), Filipinos would gather spirit is manifested by the support, sponsorship of the annual Pista sa for a fiesta in the middle of town to participation and involvement of so Nayon (town fiesta) with the main celebrate a good harvest. -

REGIONAL DIRECTOR's CORNER January 2020

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President PHILIPPINE DRUG ENFORCEMENT AGENCY REGIONAL OFFICE-NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION PDEA Annex Bldg., NIA Northside Road, National Government Center, Barangay Pinyahan, 1100 Quezon City/Telefax:(02)8351-7433/e-mail address:[email protected]/[email protected] pdea.gov.ph PDEA Top Stories PDEA@PdeaTopStories pdeatopstories REGIONAL DIRECTOR’S CORNER January 2020 On January 6, 2020, Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO- NCR, together with IA V Mary Lyd Arguelles, QC District Officer and other members of QCDO attended the Quezon City Peace and Order Council Conference held at 15th floor high rise Building, Quezon City Hall. The conference was attended by Hon. Ma. Josefina Belmonte, Quezon City Mayor, City Administrator Michael Alimurung, Mr. Ricardo Belmonte, Secretary to the Mayor, PBGen. Ronnie Montejo, QCPD Director, Director Rufino Mendoza, Director, NICA, JTF NCR and DILG. On January 24, 2020, Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO- NCR, together with IA I Berlin Orlanes of Intelligence Division attended conference meeting re Rubita Gracia Murder Case held at the Philippine Cancer Society Bldg., 310 San Rafael Street, Malacanang Complex, City of Manila. The conference was presided by USEC Jose Joel M Sy Egco. On January 28, 2020 Director III JOEL B PLAZA Regional Director of PDEA RO-NCR led the conduct of Regional Oversight Committee on Barangay Drug Clearing Program for the clearing and declaration of the forty (40) applicant barangays that are considered as drug affected from the 6 cities throughout Metro Manila on Tuesday, held at the PDEA Main Conference Room, Brgy. -

Myron Sta. Ana, Cldpt

MSS BUSINESS SOLUTIONS st 1 Floor, Unit A2, Block 8, Lot 8, Buenmar Avenue, Phase 4 Greenland Executive Village, Barangay San Juan, Cainta, Rizal 1900 Tel. (+63)2 959.8492 | (+63)2 919.2734 Mobile (+63)917.658.3534 | (+63)933.232.6149 Website: www.MyronStaAna.net | www.MSSBizSolutions.com Email Address: [email protected] MYRON STA. ANA, CLDPT ✓ Known in the Philippines as #TheCorporateEnterTrainer for his reputation of incorporating literal entertainment and creativity into his approach in public speaking, classroom training, and team building program facilitating. ✓ Also known as the #SoftSkillsGuruofthePhilippines for being one of the most- renowned, unquestionable, and premier experts in Communication (Interpersonal, Intrapersonal, and English Language), Customer Service, Customer Experience, Leadership and Management, Personality Development, Work Attitude and Values Enhancement, Business and Work Career Success, etc. ✓ Formerly a seasoned corporate training generalist and Human Resources practitioner in Organization Development and Talent Acquisition in the BPO Industry (around 7 years) ✓ Frequent Radio and TV Resource Person for topics on Career Success, Work Excellence and Productivity, Personality Development, etc. ✓ One of the Philippines’ finest and multi-awarded advisors, training providers, and program facilitators on Communication Skills, Customer Service Skills, First-line Leadership and Management, Train the Trainer, Teamwork, and other soft skills topics ✓ Cum Laude Graduate in 2006, Bachelor in Business Teacher -

LGU Best Practices

1 Page 1-19 (Intro) 1 1/5/06, 5:50 PM 2 Page 1-19 (Intro) 2 1/5/06, 5:50 PM LOCAL GOVERNMENT FISCAL and FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT Best Practices Juanita D. Amatong Editor 3 Page 1-19 (Intro) 3 1/5/06, 5:50 PM Local Government Fiscal and Financial Management Best Practices Juanita D. Amatong, Editor Copyright © Department of Finance, 2005 DOF Bldg., BSP Complex, Roxas Blvd. 1004 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel: + 632 404-1774 or 76 Fax: + 632 521-9495 Web: http://www.dof.gov.ph Email: [email protected] First Printing, 2005. Cover design by Hoche M. Briones Photos by local governments of Santa Rosa, Malalag, San Jose de Buenavista, Quezon City, Gingoog City, and Rashel Yasmin Z. Pardo (Province of Bohol) and Niño Raymond B. Alvina (Province of Aklan). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without express permission of the copyright owners and the publisher. ISBN 971-93448-0-6 Printed in the Philippines. 4 Page 1-19 (Intro) 4 1/5/06, 5:50 PM CONTENTS About the Project ................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ................................................................................. 9 Message ................................................................................................ 11 Foreword .............................................................................................. 12 Introduction ......................................................................................... 15 Revenue Generation Charging -

Volume 44, Issue 7 (1968)

YOL XIlv July No. 7 tr6a Published monthly by the Cablerow, tnc. in the inloro3l oI tho Grand I'odgc of lho Phil' ippines, Office of Publicafion, 1440 San liarcelino. Manila l0I0I. Ro.€nteted ar cecond mail ,naller al the Manila Posr Oflice on Jun. 16, 1962. a Subscriptron - ?3.00 e year in rhe Philippines. Forcign: US $I.30 Year : coPY. - ? .35 a coPY in the PhiliPPiner. Foreign: US $0.15 STAFF, THE CABTETOW MAGAZINE OFFICERS, THE CABIETOW, INC RAYMOND E. WII'IAARI}I ,liw RAY'TAOND E. WIIMARTH, PGtul Chairman Edilor MACANIO C. NAVIA wB NESTORIO B. I\AELOCOTON, Pl/t Vice-Che irmcn Managrng tditor JUAN C. NABONG, JR. WB JOSE EDRATIN RACETA, PT\A Secretary Advarriring & Circularion Managcr OSCAR T. FUNG Trearurer CONTRTBUTORS: RW MANUEI. M. CRUDO NES'ORTO r l ErocoToN Businesc Manegcr VW AURETIO I.. CORCUERA ANIONIO WB CAIIXTO B. DIRECTORS: WB AGUSIIN t. GAI.ANG WB EUGENIO PADUA MANUEI I'iI. CRUDO JOSE E. RACEIA BRO. PRCSP:RO PAJARITI.AGA EDGAR t. SHEPIEY WIII.IAM C- COUNCETT VW IORENZO N. TATATAIA DAiAASO C. TRIA PEDRO R. TRANCI5CO IN THIS ISSUE Page ,| GRAND MASTER'S MESSAGE EDITORIAL 2 THE ANSWER RW Manu:l M. Crudo 3 SCIENTIFIC PROGRESS CHANGES THE WORTD . WB Eugenio Padua 5 MpSONS ARE ECUMENICAT Jus'o C.rnare, Jr. 7 GOVERN YOURSELVES ACCORDINGLY VW Lorenzo N. Taletala 8 GRAVEL AND SAND OTF/NBM 1] VITAL MASONRY V,'B Apolonio A iibu c o t3 ALL ABOUT ECUMENISM .. NBM l5 THE EASTTRN STAR . Sis. Asuncion T. Salcedo, WM t7 JO.DE RAS SELECTION r9 WHY RAINBOW? 2\ !hIAUGURAL ADDRESS, ,"" .",i., Loas" + r8; .