Sciascia's Art of Detection by Gillian Ania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highway 101 Decision Time: IT’S NOW…OR NEVER!

The BEST things in life are FREE MINEARDS MISCELLANY 19 – 26 April 2012 Vol 18 Issue 16 With GasPods, Bob Evans saves fuel putting the pedal to the metal; Beautiful You’s Megan Simon profiled in The The Voice of the Village SSINCE 1995S New York Times, p. 6 THIS WEEK IN MONTECITO, P. 10 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS, P. 40 • MONTECITO EATERIES, P. 42 Highway 101 Decision Time: IT’S NOW…OR NEVER! Former Montecito Association President J’Amy Brown sounds the alarm over upcoming ten-year highway construction project that could change Montecito forever (story begins on page 21) MUS Carnival Dr. Seuss is the theme again as 43rd annual event – sponsored by Montecito Bank & Trust – takesDr. overSeuss MUS is campusthe theme on Saturday again as April 28, 43rd annual(story event on page – sponsored 12) by Montecito Bank & Trust – takes over MUS campus on Real Estate Four homes priced at just under REAL ESTATE VIEW & $3 million look like Best Buys to 93108 OPEN HOUSE DIRECTORY P.44 Mark Hunt, p. 37 2 MONTECITO JOURNAL • The Voice of the Village • 19 – 26 April 2012 The Premiere Estates of Montecito & Santa Barbara Offered by RANDY SOLAKIAN (805) 565-2208 www.montecitoestates.com License #00622258 Exclusive Representation for Marketing & Acquisition Additional Exceptional Estates Available by Private Consultation 8.4 acres - Ready to Build Montecito - $3,200,000 (additional 28 acres available) 19 – 26 April 2012 MONTECITO JOURNAL 3 INSIDE THIS ISSUE 5 Editorial Bob Hazard urges all to attend Caltrans meeting concerning 101 widening Splish 6 Montecito Miscellany -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

ORGANIZED CRIME: Sect

ORGANIZED CRIME: Sect. 302 SOCIOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ITALIAN MAFIA SOC 260 Fs January Term 2016 Dr. Sandra Cavallucci NOTE on section: once enrolled, students are required to regularly attend the section of the course that they are enrolled in. Switching sections during the course is not allowed. Credit Hours: 3 Contact Hours: 45 Additional Costs: Approx 20 Euro (details in point #10) Teacher contact: available to see students before and after class: [email protected] 1 - DESCRIPTION One of a long list of Italian words adopted in many other languages, “mafia” is now applied to a variety of criminal organizations around the world. This course examines organized crime in Italy in historical, social and cultural perspective, tracing its growth from the nineteenth century to the present. The chief focus is on the Sicilian mafia as the original and primary form. Similar organizations in other Italian regions, as well as the mafia in the United States, an outgrowth of Sicilian mafia, are also considered. The course analyzes sociological aspects of the mafia including language, message systems, the “code of silence,” the role of violence, structures of power, and social relationships. Also examined are the economics of organized crime and its impact on Italian society and politics. 2 - OBJECTIVES, GOALS and OUTCOMES The objective of this course is to give students an accurate and in-depth understanding of the Italian (Sicilian) mafia. Most foreigners tend to look at the mafia through stereotypes, after forming their impressions of the mafia through popular movies but few go beyond these cinematic images to learn the truth about this criminal phenomenon: the course aims to give the student a completely different picture of the mafia. -

Appel À Contribution Édito Appel À Archive

ÉDITO Lettre envoyée par le président de l’association Home Cinéma à toutes les salles de cinéma parisiennes et aux institutions culturelles françaises , ou par mail à Bonjour, Depuis septembre 2019, l’association Home Cinéma que je préside occupe le cinéma [email protected] La Clef pour en empêcher la fermeture. Vous savez toutes et tous, comme moi, l’importance de cette salle et combien elle ne menace aucunement l’écosystème du paysage cinématographique français. Bien au contraire, elle complémente la production dominante sans lui porter préjudice, sans APPEL À ARCHIVE d'un numéro spécial, vue de la préparation En nous sommes à la recherche de tout document ou ou témoignages (photographies d'archives depuis sa du cinéma La Clef sur l'histoire autres) création. par courrier au nous les adresser pouvez Vous 34, rue Daubenton, 75005 Paris suivante : l'adresse de nous préciser leur n'oubliez pas P.S. : auteur•rice•s. et/ou provenance compétition déloyale. Ce cinéma a toujours accueilli des films précarisés et/ou laissé leur chance et du temps à des œuvres que les autres salles ne pouvaient plus garder sur leurs écrans. Nous savons votre soutien et vous en remercions. Mais aujourd’hui, il est urgent The Musketeers of Pig Alley, David Wark Griffith, 1912 que vous fassiez un pas supplémentaire pour prendre part à cette lutte. Son issue ne dépend plus de nous, l’association Home Cinéma, mais bien de vous, et de notre capacité à nous fédérer. La menace que constitue le groupe SOS concerne l’ensemble du secteur culturel parisien et français, et nous devons, collectivement, prendre la mesure de ce que cela signifie. -

Orizzonti © Edizioni Kaplan 2012 Via Saluzzo, 42 Bis - 10125 Torino Tel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Università di Macerata orizzonti © edizioni kaplan 2012 Via Saluzzo, 42 bis - 10125 Torino Tel. e fax 011-7495609 [email protected] www.edizionikaplan.com ISBN 978-88-89908-73-0 Anton Giulio Mancino Schermi d’inchiesta Gli autori del film politico-indiziario italiano k a p l a n Indice Introduzione 7 Capitolo 1 25 Carlo Lizzani: realtà e verità Capitolo 2 46 Francesco Rosi: caso e causalità Capitolo 3 89 Damiano Damiani: diritto e rovescio Capitolo 4 125 Giuseppe Ferrara: strategia dell’attenzione Appendici: Documenti inediti 155 Documento su La terra trema: Indagine su agitazioni operaie e 157 contadine (1947) Primo documento su Salvatore Giuliano: Appunto per il direttore 163 generale (1961) Secondo documento su Salvatore Giuliano: Trama e giudizio della 165 Direzione Generale dello Spettacolo (1961) Terzo documento su Salvatore Giuliano: Appunto per l’onorevole 173 ministro (1961) Cos’è il cinema e perché farlo di Giuseppe Ferrara (2009) 181 Bibliografia 189 Indice dei nomi e dei film citati 199 Introduzione Questo libro nasce dall’esigenza di sviluppare un percorso di ricerca iniziato nel 2008 con Il processo della verità. Le radici del film politico-indiziario ita- liano, dove per l’appunto non si è guardato tanto al contributo specifico dei singoli autori coinvolti, di cui pure sono state esaminate alcune opere o parti importanti di esse, quanto piuttosto – lo ricordiamo – a quella corrente di energia euristica, una preoccupazione per gli eccessivi impe- dimenti alla conoscenza politica della verità, o della verità politica […] che attraversa il film in un particolare punto o momento, chetransita con maggiore o minore intensità da un film all’altro, esattamente come fa il potere con gli individui riducendoli a semplici elementi di raccordo. -

«The Witch Trials»

An unique dramatic evening with one of the most beloved Italian star of all time OORRNNEELLLLAA MMUUTTII on stage play by Silvano Spada. Based on unbelievable true story “This is the real hymn of the women” (Ornella Muti) ««TTHHEE WWIITTCCHH TTRRIIAALLSS»» «Processo alla strega» Directed by Enrico Maria Lamanna WWHHOO DDOOEESS NNOOTT LLOOVVEE HHAATTEESS LLOOVVEERRSS On March 20, 1428, in the square of the Umbrian town of Todi, where the Duomo stands and surrounds the ancient palaces of the Signoria, a tribunal witр accuser of excellence, created by the connivance between religious power and civil authority, condemned Francesco Matteuccia (Ornella Muti) as the first woman to be sent to the stake with the accusation of witchcraft. A faithful reproduction of the climate of a time when it was difficult to be a woman and wondered what God might be so powerful would be forbidding man to fall in love. The story about the time when the world was dominated by power and harassment, where the man has absolute dominion, and where, in the name of evangelical dictates only true on paper, the woman trying to raise her head and go against it must be punished to overthrow the initiatives that Have the feeling of autonomy and independence. Matteuccia becomes a symbol of female independence, and as such should be stopped with the weapon of aridity and antidiabolic crusade. Ornella Muti adds beauty and beauty to a precise and painful act together with the dignity that makes him the representative of all women subjected to injustice. She performing in the extraordinary figure of Matteuccia, a fragile and helpless woman, accused of loving and screaming with pain: "Who does not He hates who he loves." "A desperately beautiful show," says good director Lamanna, "painfully timely and strong. -

History of Modern Italy General

Santa Reparata International School of Art COPYRIGHT © 2010 All rights reserved Course Syllabus Course Title: History of Modern Italy Course Number: EUH 3431 1. COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course will study the history of Modern Italy from the Risorgimento and continue on through the development and decline of the liberal Italian state; Mussolini and Italian Fascism; World War II; and post World War II Italy; up through recent historical events. Introduction to major literary, cinematographic and artistic movements are covered as well as social aspects of Italian life including topics such as the Italian political system; the development of the Italian educational system; the roots and influence of the Italian Mafia; and the changing role of the woman in Italian society. 2. CONTENT INTRODUCTION: This course introduces students to the history and politics of modern Italy from the time of its political Unification to the present. The major topics covered throughout the course include the process of political unification in the mid-late 1800s; the birth and growth of Fascism in Italy (1922-1943); the Second World War (1940-45); the workings of governing institutions in the post-war period (1946-48); the role of the Church; political parties and movements; the process of massive industrialization (1950-60’s); political terrorist events (1960-80’s); as well as political corruption and political conspiracy. There will also be an in-depth analysis of the political crisis and transformation of the Italian democratic system in the early 1990s. 3. COURSE RATIONALE : The course is particularly recommended to all those students that want to gain an in-depth knowledge of the contemporary social and political history of Italy. -

A Socio-Economic Study of the Camorra Through Journalism

A SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY OF THE CAMORRA THROUGH JOURNALISM, RELIGION AND FILM by ROBERT SHELTON BELLEW (under the direction of Thomas E. Peterson) ABSTRACT This dissertation is a socio-economic study of the Camorra as portrayed through Roberto Saviano‘s book Gomorra: Viaggio nell'impero economico e nel sogno di dominio della Camorra and Matteo Garrone‘s film, Gomorra. It is difficult to classify Saviano‘s book. Some scholars have labeled Gomorra a ―docufiction‖, suggesting that Saviano took poetic freedoms with his first-person triune accounts. He employs a prose and news reporting style to narrate the story of the Camorra exposing its territory and business connections. The crime organization is studied through Italian journalism, globalized economics, eschatology and neorealistic film. In addition to igniting a cultural debate, Saviano‘s book has fomented a scholarly consideration on the innovativeness of his narrative style. Wu Ming 1 and Alessandro Dal Lago epitomize the two opposing literary camps. Saviano was not yet a licensed reporter when he wrote the book. Unlike the tradition of news reporting in the United States, Italy does not have an established school for professional journalism instruction. In fact, the majority of Italy‘s leading journalists are writers or politicians by trade who have gravitated into the realm of news reporting. There is a heavy literary influence in Italian journalism that would be viewed as too biased for Anglo- American journalists. Yet, this style of writing has produced excellent material for a rich literary production that can be called engagé or political literature. A study of Gomorra will provide information about the impact of the book on current Italian journalism. -

Yo Soy La Revolución

YO SOY LA REVOLUCIÓN Equipo técnico artístico director Damiano Damiani productor Bianco Manini compañía de producción M.C.M. (Italia) guión Salvatore Laurani adaptación Franco Solinas argumento Salvatore Laurani fotografía Tonio Secchi montaje Renato Cinquini música original Luis Enríquez Bacalov dirección musical Bruno Nicolai supervisor musical Ennio Morricone cancion interpretada "Ya me voy", de L. E. Bacalov, por Ramón Mereles director de producción Ferruccio de Martino decorados Sergio Canevari vestuario Marilù Carteny ayudante producción Ofelia Minaldi Datos técnicos duración: 2 horas 15 minutos versión: en castellano. Technicolor. diálogos idiomas audio: inglés/ italiano, con subtítulos español formato de cine: 35 milímetros. Techniscope. 1: 2.35. formato de imagen: 16:9. DVD-Z2, Zona 2, producción Filmax (Spain / Italy) Audio Dolby Surround Estéreo. año producción cine: 1966, Italia localizaciones exteriores: Almería (España) estreno: 10-10-1969 Bilbao: Olimpia 31-08-1970 Madrid: Roxy A, Carlos III, Princesa, Consulado, Regio 18-01-1971 Barcelona: Regio, Bosque, Palacio Balañá Equipo artístico Intérpretes Personajes Gian Maria Volonté el Chuncho Klaus Kinski el Santo Lou Castel Bill Tate/el gringo Martine Beswick Adelita Carla Gravina Rosaria Andrea Checchi Don Felipe Jaime Fernández Gen. Elias Aldo Sambrell Ten. Sul Treno Spartaco Conversi Eufemio Cirillo Santiago Santos Guapo Joaquín Parra Picaro José Manuel Martín Raimundo Valentino Macchi Pedrito Guy Heron Presentación Aun hoy día es posible encontrarse por la calle a Damiano Damiani. Fue el pasado verano en Torella dei Lombardi, una pequeña ciudad de montaña, apiñada en torno a un imponente castillo-fortaleza, no lejos de Nápoles. Este director italiano es autor de algunas de las mejores películas políticas de los años setenta –prohibidas en España bajo Franco– como: Confesión de un comisario de policía al procurador de la República, y Estamos todos en libertad provisional. -

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Amanda Rose Bush Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso Buscetta Committee: Paola Bonifazio, Supervisor Daniela Bini Circe Sturm Alessandra Montalbano Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso by Amanda Rose Bush Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Dedication I dedicate this disseration to Phoebe, my big sister and biggest supporter. Your fierce intelligence and fearless pursuit of knowledge, adventure, and happiness have inspired me more than you will ever know, as individual and as scholar. Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the sage support of Professor Paola Bonifazio, who was always open to discussing my ideas and provided both encouragement and logistical prowess for my research between Corleone, Rome, Florence, and Bologna, Italy. Likewise, she provided a safe space for meetings at UT and has always framed her questions and critiques in a manner which supported my own analytical development. I also want to acknowledge and thank Professor Daniela Bini whose extensive knowledge of Sicilian literature and film provided many exciting discussions in her office. Her guidance helped me greatly in both the genesis of this project and in understanding its vaster implications in our hypermediated society. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Circe Sturm and Professor Alessandra Montalbano for their very important insights and unique academic backgrounds that helped me to consider points of connection of this project to other larger theories and concepts. -

Ma Questa Piovra Non Colpisce Più EESEEGQÀ GON HAEOEF

L'UNITÀ/DOMENICA 152 7 GENNAIO 1985 MILANO — -Io spero che la ma per intrappolare definiti volte non ammette scusanti. gente non si spaventi. Arrivare •BilSSMSI Parlano gli interpreti del balletto che vamente il principe. Chiaro Nella musica, ma anche in tut a teatro con l'idea di vedere II che un personaggio simile ri te le altre componenti dello lago dei cigni e trovarsi difron' debutta il 31 alla Scala, in una versione «filologica» chiede > molta espressività; spettacolo. Dalla coreografìa te qualcosa di molto diverso adesso mi diverto a interpre firmata da Rosella Hightower, può essere uno shock!-. È l'e tarlo. Ma devo dire che il di la direttrice del balletto della sordio di Maurizio Bellezza, il vertimento è subentrato in un Scala, ai costumi di Anna Anni, ventisettenne danzatore mila secondo • tempo. All'inizio il dalle scene alla regia firmate nese che, abbandonata la Scala mio fisico, sentendo la musica entrambe da Zeffirelli. Ma il peliamoli nel 1981 per il London Festival di Ciaikovski che non è cam balletto italiano, negli ultimi Ballet, è tornato a casa apposi biata, danzava d'istinto i passi anni, ha avuto un battage pub tamente per vestire i panni del tradizionali-. blicitario più invadente... principe Sigfrido nel Lago dei Doppio cigno cigni «rifondato» da Franco Renata Calderini, ventinove • E a ragione, sorride Anna Zeffirelli. Ma rifondato davve anni, transfuga al London Fe Rizzi. -Sulla carta ci sono tutti ro? \ * stival Ballet con Maurizio Bel gli ingredienti per l'avveni lezza, è della stessa opinione: mento d'eccezione. Il cast è di 'Andiamoci piano-, spiega •Per mela difficoltà è stata so primissimo livello. -

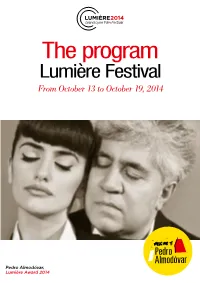

The Program Lumière Festival from October 13 to October 19, 2014

The program Lumière Festival From October 13 to October 19, 2014 Pedro Almodóvar, Lumière Award 2014 RETROSPECTIVES 1964 : A certain Bob Robertson... The Invention of the Italian Western Pedro Almodóvar: Lumière Award 2014 With A Fistful of Dollars, Sergio Leone (alias Bob The filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar will receive the Robertson) made the first Italian western and Lumière Award for his filmography, for his intense its success gave rise to a decade of continuous passion for the cinema that nourishes his work, waves of the genre by the likes of Corbucci and for his generosity, exuberance, and the audacious Sollima. Lumière will screen his most iconic films, vitality he brings to the cinema. populated by individuals who are violent and offbeat, but also generous and funny. Back for the first time in many years on the big screen in Cartes blanches restored prints. to Pedro Almodóvar The Program The director has chosen two A permanent history of women categories of films: the Spanish cinema filmmakers: Ida Lupino and works that have inspired his films. Actress, writer, producer and director of postwar America, Ida Lupino was a trailblazing figure of daring cinema, audacious both in her career choices and her films, which included intriguing The Era de Claude Sautet (1960-1995) titles like The Bigamist, Never Fear, The Hitch- César and Rosalie, The Things of Life... A Hiker, or Not Wanted. rediscovery of realistic and timeless films by a unique director, a sensitive analyst of human Splendors of Restoration 2014 relations (friends, or lovers) who has painted The finest restorations of the year, some to be an intimate portrait of France over several re-released in theaters in the coming months.