Shipping Watermelons on the Coast Line and Se

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semiannual Report to Congress Go Green!

Go Green! Consumes less energy than car or air travel* Semiannual Report to Congress Report #41 H 10/01/09 – 3/31/10 ON THE COVER Amtrak® Empire Builder® Message from the Inspector General am pleased to present the first Semiannual Report We made a series of recommendations to improve to Congress since my appointment as Amtrak the effectiveness and efficiency of training and IInspector General in November 2009. In addition employee development, focusing on developing and to reporting on the Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) implementing a corporate-wide training and employee accomplishments during the six-month period ending development strategy. This would ensure that training March 31, 2010, I am identifying several significant aligns with the overall corporate strategy and provides challenges the OIG faces and the ongoing and planned employees with the skills needed to assume leadership actions we are pursuing to overcome the challenges. roles in the future. Significant Accomplishments Management recently agreed with all of our recommendations and provided a plan to implement During this semi-annual reporting period, the OIG them. It is important, however, for management to continued to identify opportunities to reduce costs, stay focused on making near-term improvements, improve management operations, enhance revenue, and because effective training and development practices institute more efficient and effective business processes. will be a key component of Amtrak’s ability to deliver For example: high quality services. H An OIG audit of the monthly on time performance H The Office of Investigations was instrumental in (OTP) bills and schedules from April 1993 through securing convictions and restitutions in multiple theft April 2004 disclosed that CSX inaccurately billed schemes. -

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

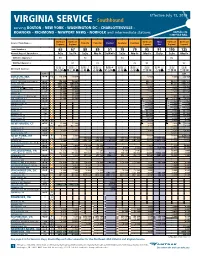

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System > See Page 46 >

THENational Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers CHAMPION July 2013 Hair Microscopy Review Project An Historic Breakthrough For Law Enforcement and A Daunting Challenge For the Defense Bar Eliminating Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System > See page 46 > LAS VEGAS, NV > > SEE PAGE 3 October 3-5, 2013 / NACDL & NCDD’s 17th Annual DWI Means Defend With Ingenuity Conference SAVANNAH, GA > > SEE PAGE 20 October 16-19, 2013 / NACDL’s 2013 Fall Meeting & Seminar WASHINGTON, DC > > SEE BROCHURE October 24-25, 2013 / 9th Annual Defending the White Collar Case LAS VEGAS, NV > > SEE PAGE 29 November 21-22, 2013 / NACDL’s 6th Annual Defending the Modern Drug Case Conference ASPEN, CO > > SEE PAGE 53 January 12-17, 2014 / 34th Annual Advanced Criminal Law Seminar NEW ORLEANS, LA > > SEE PAGE 60 March 5-8, 2014 / NACDL’s 2014 Collateral Consequences Conference & Midwinter Meeting WWW .NACDL .OR G ©Bill Fritsch | Artville Similarly, eliminating racial disparities in the criminal justice system can be achieved by recognizing the power we all possess to get rid of personal biases and structural racism in the criminal justice system. In essence, every police officer, prosecutor, defense attorney, lawyer, judge, juror, and community mem - ber has to do more, care more, and be more under - standing and willingly acknowledge the biases every - one possesses. In October 2012 NACDL and other organizations sponsored a conference entitled Criminal Justice in Racial Disparities the 21st Century: Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System. The people who attended came to the table acknowledging that racial and ethnic disparities in the criminal justice The Answer Lies Within system exist. -

In Loving Memory Alvis Kellam Nicolas Ryan Brian Ryan Abraham Newbold Kenneth Bates Rahsaan Cardin Of

Active Pallbearers In Loving Memory Alvis Kellam Nicolas Ryan Brian Ryan Abraham Newbold Kenneth Bates Rahsaan Cardin of Flower Attendants Family Members and Friends Repass Seasons 52 5096 Big Island Drive 32246 Acknowledgement Our sincere thanks to our family members and friends for every act of kindness, support, sympathy, and your prayers. We appreciate you and the love you give. ~ The Longmire Family ~ James Zell Longmire, Jr. Sunset Sunrise Arrangements in care of: August 25, 1930 July 17, 2021 Service 10:00 AM, Saturday, August 8, 2021 4315 N. Main Street 410 Beech Street Jacksonville, FL 32206 Fernandina Beach, FL 32034 Samuel C. Rogers, Jr. Memorial Chapel 904-765-1234 4315 North Main Street Tyrone S. Warden, FDIC www.tswarden.com Jacksonville, Florida 32206 Rev. Michael Gene Longmire, Officiating Order of Service Pastor Burdette Williams, Sr., Presiding Obituary Pastor Philip Mercer, Musician James Zell Longmire, Jr. (90) went home to be with the Lord on Saturday, July 17, 2021 at Memorial Hospital, Jacksonville, FL of Pneumonia Processional ……………………………….………………. Orlin Lee and other underlying health problems. James, “I Know It Was the Blood” also known as J.Z., Jim, Cap, and Junior was born Scripture ..…………………………… Pastor Burdette Williams, Sr. in Tallahassee, FL on August 25, 1930 to the late Reverend James Zell Longmire, Sr. and Lillie Psalm 145:9-10, 19 Longmire of Alabama. Psalm 30:16 Prayer ……………………………….…………... Rev. D’Metri Burke James, the sixth child out of seven, was an ambitious child and dedicated his life to Christ at an early age. He was a gospel singer Musical Selection ...……………………………………….. Orlin Lee in his father’s group along with his siblings called the “Jolly Junior “His Eye Is on the Sparrow” Jubilee”. -

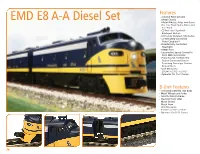

EMD E8 A-A Diesel

2010 volume 2 - part1.qxp 4/9/2010 12:20 PM Page 24 Features - Colorful Paint Scheme EMD E8 A-A Diesel Set - Metal Chassis - Metal Wheels, Axles and Gears - Die-Cast Truck Sides, Pilots and Fuel Tank - (2) Precision Flywheel- Equipped Motors - Intricately Detailed ABS Bodies - (2) Remotely Controlled Proto-Couplers™ - Directionally Controlled Headlight - Metal Horn - Locomotive Speed Control In Scale MPH Increments - Proto-Sound 2.0 With The Digital Command System Featuring Passenger Station Proto-Effects - Unit Measures: 29 3/4” x 2 1/2” x 3 1/2” - Operates On O-31 Curves B-Unit Features - Intricately Detailed ABS Body - Metal Wheels and Axles - Colorful Paint Scheme - Die-Cast Truck Sides - Metal Chassis - Metal Horn - Unit Measures: 13 1/2” x 2 1/2” x 3 1/2” - Operates On O-31 Curves 24 2010 volume 2 - part1.qxp 4/9/2010 12:20 PM Page 25 In the mid-1930's, as the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors was trying to inter- est railroads in diesel passenger power, it experimented a lot with exterior design. Looking at EMD's worm-like yellow and brown Union Pacific M-10000, its gleaming stainless steel Burlington Zephyr, or the boxy, Amtrak - E8 A-A Diesel Engine Set just-plain-ugly early Santa Fe units, it's appar- 30-2996-1 w/Proto-Sound 2.0 $349.95 Add a Matching ent that here was a new function looking for Amtrak - E8 B-Unit Passenger Set 30-2996-3 Non-Powered $119.95 its form. The first generation of road diesels See Page 48 found its form in 1937 when the initial E- units, built for the B&O, inaugurated the clas- sic "covered wagon" cab unit design that would last for decades on both freight and passenger diesels. -

Up North on Vacation: Tourism and Resorts in Wisconsin's North Woods 1900-1945 Author(S): Aaron Shapiro Source: the Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol

Up North on Vacation: Tourism and Resorts in Wisconsin's North Woods 1900-1945 Author(s): Aaron Shapiro Source: The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 89, No. 4 (Summer, 2006), pp. 2-13 Published by: Wisconsin Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4637185 Accessed: 17/08/2010 15:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=whs. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wisconsin Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Wisconsin Magazine of History. http://www.jstor.org This North Shore Line poster evokes the tranquility, scenery, and recreational opportunities of northern Wisconsinthat drew vacationers. -

WU Editorials

volume three, number four a supplement to walthers ho, n&z and big trains reference books Walthers Adds New Suppliers Small Cars Always on the lookout for new and exciting products, Walthers has added three more suppliers to their ranks. JR Miniatures (#346), Raildriver (#560) and Tayden Design (#702) Make A Big each offer their own line of unique products sure to be a benefit to any modeler. Impact JR Miniatures computer. Programmable keys put commands on the controller so you can put the keyboard away. They also have CD-ROM Cyclopedias — a great resource for modelers Tayden Design 490-19110 BMW Z8 Convertible 346-H1305 Rough Stone Bridge Adding structures to nearly any size layout just got easier. Featuring a line of finely detailed, resin-cast buildings, JR Miniatures, has buildings available in N, HO and O 490-19690 Porsche 356B with Camping Scales. Great for rural scenes or small Trailer towns, all items come undecorated allowing Model Power announces its latest modelers to paint them any way they want line of HO Scale vehicles, Model in order to fit their modeling era or overall Power Minis. These diecast town scheme. beauties will make a lot of noise Raildriver 702-13632 Train Trek Automation Station traveling down any highway or Tayden Design features a line of software small road on your layout. Each car that allows modelers to computerize features a diecast metal body, full everything from operations to equipment vehicle interior, rubber tires and maintenance records. Designed especially accurate wheels. They are also fully for model railroading, Tayden Design offers painted, and feature separately modelers a variety of computer programs applied details. -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) New Jersey

Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) for New Jersey By ORF 467 Transportation Systems Analysis, Fall 2004/05 Princeton University Prof. Alain L. Kornhauser Nkonye Okoh Mathe Y. Mosny Shawn Woodruff Rachel M. Blair Jeffery R Jones James H. Cong Jessica Blankshain Mike Daylamani Diana M. Zakem Darius A Craton Michael R Eber Matthew M Lauria Bradford Lyman M Martin-Easton Robert M Bauer Neset I Pirkul Megan L. Bernard Eugene Gokhvat Nike Lawrence Charles Wiggins Table of Contents: Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to Personal Rapid Transit .......................................................................................... 3 New Jersey Coastline Summary .................................................................................................... 5 Burlington County (M. Mosney '06) ..............................................................................................6 Monmouth County (M. Bernard '06 & N. Pirkul '05) .....................................................................9 Hunterdon County (S. Woodruff GS .......................................................................................... 24 Mercer County (M. Martin-Easton '05) ........................................................................................31 Union County (B. Chu '05) ...........................................................................................................37 Cape May County (M. Eber '06) …...............................................................................................42 -

Technical Options to Achieve Additional Emissions and Risk Reductions from California Locomotives and Railyards

Technical Options to Achieve Additional Emissions and Risk Reductions from California Locomotives and Railyards August 2009 This Page Iintentionally Left Blank State of California California Environmental Protection Agency AIR RESOURCES BOARD Stationary Source Division Technical Options to Achieve Additional Emissions and Risk Reductions from California Locomotives and Railyards August 2009 This document has been reviewed by the staff of the Air Resources Board and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Air Resources Board, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. August 2009 i This Page Intentionally Left Blank August 2009 ii Acknowledgments This report was prepared with assistance and support from the other divisions and offices of the Air Resources Board. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the assistance and cooperation that we have received from many individuals and organizations. Principal Author Harold Holmes, Manager, Engineering Evaluation Section Mike Jaczola Contributors Eugene Yang, Ph.D. Hector Castaneda Ambreen Afshan Alexander Mitchell Stephen Cutts Reviewed by: Bob Fletcher, Chief, Stationary Source Division Dean C. Simeroth, Chief, Criteria Pollutants Branch August 2009 iii This Page Intentionally Left Blank August 2009 iv Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 A. Background...................................................................................................................... -

2021 Georgia State Rail Plan

State Rail Plan Georgia State Rail Plan Final Report Master Contract #: TOOIP1900173 PI # 0015886 State Rail Plan Update – FY 2018 4/6/2021 State Rail Plan Contents 1. The Role of Rail in Statewide Transportation ......................................................................................... 1-7 1.1. Purpose and Content ...................................................................................................................... 1-7 1.2. Multimodal Transportation System Goals ...................................................................................... 1-8 1.3. Role of Rail in Georgia’s Transportation Network .......................................................................... 1-8 1.4. Role of Passenger Rail in Georgia Transportation Network ......................................................... 1-16 1.5. Institutional Governance Structure of Rail in Georgia ................................................................. 1-19 1.6. Role of Federal Agencies .............................................................................................................. 1-29 2. Georgia’s Existing Rail System ................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1. Description and Inventory .............................................................................................................. 2-1 2.2. Trends and Forecasts ...................................................................................................................