Editing Sgml Documents with the Emacs Text Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

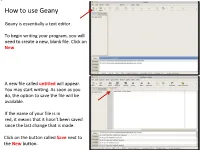

Geany Tutorial

How to use Geany Geany is essentially a text editor. To begin writing your program, you will need to create a new, blank file. Click on New. A new file called untitled will appear. You may start writing. As soon as you do, the option to save the file will be available. If the name of your file is in red, it means that it hasn’t been saved since the last change that is made. Click on the button called Save next to the New button. Save the file in a directory you had previously created before you launched Geany and name it main.cpp. All of the files you will write and submit to will be named specifically main.cpp. Once the .cpp has been specified, Geany will turn on its color coding feature for the C++ template. Next, we will set up our environment and then write a simple program that will print something to the screen Feel free to supply your own name in this small program Before we do anything with it, we will need to configure some options to make your life easier in this class The vertical line to the right marks the ! boundary of your code. You will need to respect this limit in that any line of code you write must not cross this line and therefore be properly, manually broken down to the next line. Your code will be printed out for The line is not where it should be, however, and grading, and if your code crosses the we will now correct it line, it will cause line-wrapping and some points will be deducted. -

Software Tools: a Building Block Approach

SOFTWARE TOOLS: A BUILDING BLOCK APPROACH NBS Special Publication 500-14 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Bureau of Standards ] NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards^ was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to pro- mote public safety. The Bureau consists of the Institute for Basic Standards, the Institute for Materials Research, the Institute for Applied Technology, the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology, the Office for Information Programs, and the ! Office of Experimental Technology Incentives Program. THE INSTITUTE FOR BASIC STANDARDS provides the central basis within the United States of a complete and consist- ent system of physical measurement; coordinates that system with measurement systems of other nations; and furnishes essen- tial services leading to accurate and uniform physical measurements throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce. The Institute consists of the Office of Measurement Services, and the following center and divisions: Applied Mathematics — Electricity — Mechanics — Heat — Optical Physics — Center for Radiation Research — Lab- oratory Astrophysics^ — Cryogenics^ — Electromagnetics^ — Time and Frequency*. THE INSTITUTE FOR MATERIALS RESEARCH conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measure- ment, standards, and data on the properties of well-characterized materials needed by industry, commerce, educational insti- tutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; and develops, produces, and distributes standard reference materials. -

Text Editing in UNIX: an Introduction to Vi and Editing

Text Editing in UNIX A short introduction to vi, pico, and gedit Copyright 20062009 Stewart Weiss About UNIX editors There are two types of text editors in UNIX: those that run in terminal windows, called text mode editors, and those that are graphical, with menus and mouse pointers. The latter require a windowing system, usually X Windows, to run. If you are remotely logged into UNIX, say through SSH, then you should use a text mode editor. It is possible to use a graphical editor, but it will be much slower to use. I will explain more about that later. 2 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl Text mode editors The three text mode editors of choice in UNIX are vi, emacs, and pico (really nano, to be explained later.) vi is the original editor; it is very fast, easy to use, and available on virtually every UNIX system. The vi commands are the same as those of the sed filter as well as several other common UNIX tools. emacs is a very powerful editor, but it takes more effort to learn how to use it. pico is the easiest editor to learn, and the least powerful. pico was part of the Pine email client; nano is a clone of pico. 3 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl What these slides contain These slides concentrate on vi because it is very fast and always available. Although the set of commands is very cryptic, by learning a small subset of the commands, you can edit text very quickly. What follows is an outline of the basic concepts that define vi. -

Basic Guide: Using VIM Introduction: VI and VIM Are In-Terminal Text Editors That Come Standard with Pretty Much Every UNIX Op

Basic Guide: Using VIM Introduction: VI and VIM are in-terminal text editors that come standard with pretty much every UNIX operating system. Our Astro computers have both. These editors are an alternative to using Emacs for editing and writing programs in python. VIM is essentially an extended version of VI, with more features, so for the remainder of this discussion I will be simply referring to VIM. (But if you ever do research and need to ssh onto another campus’s servers and they only have VI, 99% of what you know will still apply). There are advantages and disadvantages to using VIM, just like with any text editors. The main disadvantage of VIM is that it has a very steep learning curve, because it is operated via many keyboard shortcuts with somewhat obscure names like dd, dw, d}, p, u, :q!, etc. In addition, although VIM will do syntax highlighting for Python (ie, color code things based on what type of thing they are), it doesn’t have much intuitive support for writing long, extensive, and complex codes (though if you got comfortable enough you could conceivably do it). On the other hand, the advantage of VIM is once you learn how to use it, it is one of the most efficient ways of editing text. (Because of all the shortcuts, and efficient ways of opening and closing). It is perfectly reasonable to use a dedicated program like emacs, sublime, canopy, etc., for creating your code, and learning VIM as a way to edit your code on the fly as you try to run it. -

Using the Linux Virtual Machine

Using the Linux Virtual Machine Update: On my computer I had problems with screen resolution and the VM didn't resize with the window and take the full width when in fullscreen mode. This was fixed with installation of an additional package. In a console window (see below how to pen that), I gave this command: sudo aptget install virtualboxguestdkms This asks for the password. That is "genomics". After restarting the VM, the screen resize works fine. Some programs are found in the menu at the bottomleft corner. Many programs are commandline only and not in the menu. To use the command line, start the console by clicking the icon in the bottom panel. Execute the following commands to create a new directory in your home folder "~/" for today’s exercises: mkdir ~/session_1 cd ~/session_1 Open the file browser to see what you did. The Shared Folders is under /media. On the file browser you can change to directory view using the pull down menu on the topleft corner: Click then "media" and "sf_evogeno". Using RStudio Click this link: https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B3Cf0QL4k1PTkZ5QVdEQ1psRUU and select to open the file in RStudio. Save the file in the folder "session_1" that you created above. The script requires two R libraries that are not installed. Install them by typing the following commands in the R console window: install.packages("ggplot2") install.packages("reshape") Now you are ready to run the script e.g. by clicking the "Source" button in the topright corner of the file editor window. -

The Kate Handbook

The Kate Handbook Anders Lund Seth Rothberg Dominik Haumann T.C. Hollingsworth The Kate Handbook 2 Contents 1 Introduction 10 2 The Fundamentals 11 2.1 Starting Kate . 11 2.1.1 From the Menu . 11 2.1.2 From the Command Line . 11 2.1.2.1 Command Line Options . 12 2.1.3 Drag and Drop . 13 2.2 Working with Kate . 13 2.2.1 Quick Start . 13 2.2.2 Shortcuts . 13 2.3 Working With the KateMDI . 14 2.3.1 Overview . 14 2.3.1.1 The Main Window . 14 2.3.2 The Editor area . 14 2.4 Using Sessions . 15 2.5 Getting Help . 15 2.5.1 With Kate . 15 2.5.2 With Your Text Files . 16 2.5.3 Articles on Kate . 16 3 Working with the Kate Editor 17 4 Working with Plugins 18 4.1 Kate Application Plugins . 18 4.2 External Tools . 19 4.2.1 Configuring External Tools . 19 4.2.2 Variable Expansion . 20 4.2.3 List of Default Tools . 22 4.3 Backtrace Browser Plugin . 25 4.3.1 Using the Backtrace Browser Plugin . 25 4.3.2 Configuration . 26 4.4 Build Plugin . 26 The Kate Handbook 4.4.1 Introduction . 26 4.4.2 Using the Build Plugin . 26 4.4.2.1 Target Settings tab . 27 4.4.2.2 Output tab . 28 4.4.3 Menu Structure . 28 4.4.4 Thanks and Acknowledgments . 28 4.5 Close Except/Like Plugin . 28 4.5.1 Introduction . 28 4.5.2 Using the Close Except/Like Plugin . -

ENCM 335 Fall 2018: Command-Line C Programming on Macos

page 1 of 4 ENCM 335 Fall 2018: Command-line C programming on macOS Steve Norman Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Calgary September 2018 Introduction This document is intended to help students who would like to do ENCM 335 C pro- gramming on an Apple Mac laptop or desktop computer. A note about software versions The information in this document was prepared using the latest versions of macOS Sierra version 10.12.6 and Xcode 9.2, the latest version of Xcode available for that version of macOS. Things should work for you if you have other but fairly recent versions of macOS and Xcode. If you have versions that are several years old, though you may experience difficulties that I'm not able to help with. Essential Software There are several key applications needed to do command-line C programming on a Mac. Web browser I assume you all know how to use a web browser to find course documents, so I won't say anything more about web browsers here. Finder Finder is the tool built in to macOS for browsing folders and files. It really helps if you're fluent with its features. Terminal You'll need Terminal to enter commands and look at output of commands. To start it up, look in Utilities, which is a folder within the Applications folder. It probably makes sense to drag the icon for Terminal to the macOS Dock, so that you can launch it quickly. macOS Terminal runs the same bash shell that runs in Cygwin Terminal, so commands like cd, ls, mkdir, and so on, are all available on your Mac. -

O'reilly GNU Emacs Pocket Reference.Pdf

Page i GNU Emacs Pocket Reference Debra Cameron Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Page ii GNU Emacs Pocket Reference by Debra Cameron Copyright ã 1999 O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Editor: Gigi Estabrook Production Editor: Claire Cloutier LeBlanc Production Services: Omegatype Typography, Inc. Cover Design: Edie Freedman Printing History: January 1999: First Edition Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O'Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. The association between the image of a gnu and the topic of GNU Emacs is a trademark of O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. This book is printed on acid-free paper with 85% recycled content, 15% post-consumer waste. O'Reilly & Associates is committed to using paper with the highest recycled content available consistent with high quality. ISBN: 1-56592-496-7 [11/99] Page iii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Emacs Commands 1 Conventions 2 1. Emacs Basics 2 2. Editing Files 5 3. Search and Replace Operations 10 4. Using Buffers and Windows 15 5. Emacs as a Work Environment 19 6. -

Command Line Interface (Shell)

Command Line Interface (Shell) 1 Organization of a computer system users applications graphical user shell interface (GUI) operating system hardware (or software acting like hardware: “virtual machine”) 2 Organization of a computer system Easier to use; users applications Not so easy to program with, interactive actions automate (click, drag, tap, …) graphical user shell interface (GUI) system calls operating system hardware (or software acting like hardware: “virtual machine”) 3 Organization of a computer system Easier to program users applications with and automate; Not so convenient to use (maybe) typed commands graphical user shell interface (GUI) system calls operating system hardware (or software acting like hardware: “virtual machine”) 4 Organization of a computer system users applications this class graphical user shell interface (GUI) operating system hardware (or software acting like hardware: “virtual machine”) 5 What is a Command Line Interface? • Interface: Means it is a way to interact with the Operating System. 6 What is a Command Line Interface? • Interface: Means it is a way to interact with the Operating System. • Command Line: Means you interact with it through typing commands at the keyboard. 7 What is a Command Line Interface? • Interface: Means it is a way to interact with the Operating System. • Command Line: Means you interact with it through typing commands at the keyboard. So a Command Line Interface (or a shell) is a program that lets you interact with the Operating System via the keyboard. 8 Why Use a Command Line Interface? A. In the old days, there was no choice 9 Why Use a Command Line Interface? A. -

Learning GNU Emacs Other Resources from O’Reilly

Learning GNU Emacs Other Resources from O’Reilly Related titles Unix in a Nutshell sed and awk Learning the vi Editor Essential CVS GNU Emacs Pocket Reference Version Control with Subversion oreilly.com oreilly.com is more than a complete catalog of O’Reilly books. You’ll also find links to news, events, articles, weblogs, sample chapters, and code examples. oreillynet.com is the essential portal for developers interested in open and emerging technologies, including new platforms, pro- gramming languages, and operating systems. Conferences O’Reilly brings diverse innovators together to nurture the ideas that spark revolutionary industries. We specialize in document- ing the latest tools and systems, translating the innovator’s knowledge into useful skills for those in the trenches. Visit con- ferences.oreilly.com for our upcoming events. Safari Bookshelf (safari.oreilly.com) is the premier online refer- ence library for programmers and IT professionals. Conduct searches across more than 1,000 books. Subscribers can zero in on answers to time-critical questions in a matter of seconds. Read the books on your Bookshelf from cover to cover or sim- ply flip to the page you need. Try it today with a free trial. THIRD EDITION Learning GNU Emacs Debra Cameron, James Elliott, Marc Loy, Eric Raymond, and Bill Rosenblatt Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Learning GNU Emacs, Third Edition by Debra Cameron, James Elliott, Marc Loy, Eric Raymond, and Bill Rosenblatt Copyright © 2005 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. -

Xemacs User's Manual

XEmacs User's Manual July 1994 (General Public License upgraded, January 1991) Richard Stallman Lucid, Inc. and Ben Wing Copyright c 1985, 1986, 1988 Richard M. Stallman. Copyright c 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 Lucid, Inc. Copyright c 1993, 1994 Sun Microsystems, Inc. Copyright c 1995 Amdahl Corporation. Permission is granted to make and distribute verbatim copies of this manual provided the copy- right notice and this permission notice are preserved on all copies. Permission is granted to copy and distribute modified versions of this manual under the con- ditions for verbatim copying, provided also that the sections entitled \The GNU Manifesto", \Distribution" and \GNU General Public License" are included exactly as in the original, and provided that the entire resulting derived work is distributed under the terms of a permission notice identical to this one. Permission is granted to copy and distribute translations of this manual into another language, under the above conditions for modified versions, except that the sections entitled \The GNU Manifesto", \Distribution" and \GNU General Public License" may be included in a translation approved by the author instead of in the original English. i Short Contents Preface ............................................ 1 GNU GENERAL PUBLIC LICENSE ....................... 3 Distribution ......................................... 9 Introduction ........................................ 11 1 The XEmacs Frame ............................... 13 2 Keystrokes, Key Sequences, and Key Bindings ............. 17 -

GNU Emacs As a Front End to LATEX

GNU Emacs as a Front End to LATEX Kresten Krab Thorup Dept. of Mathematics and Computer Science Institute of Electronic Systems Aalborg University DK-9220 Aalborg Ø Denmark [email protected] Abstract As LATEXandTEX are more widely used, the need for high-level front ends becomes urgent. This talk describes AUC TEX, one such high-level front end for LATEX, written for GNU Emacs. AUC TEX does not at all attempt to be wysiwyg; rather, it offers the author of a LATEX document a plain ascii file, together with a number of features to simplify and help the author perform certain tasks such as running (LA)TEX, finding errors, and simply typing in the document. Background — The GNU Emacs Advantages of Structure-Oriented Paradigm Editing GNU Emacs is a powerful text editor which, very AUC TEX is an application for editing (LA)TEXdoc- much like TEX, leaves the sophisticated Emacs user uments, especially LATEX. The most general advan- with the choice of affecting its behavior on demand. tage is that by knowing the general structure of a The extension language of GNU Emacs is a deriva- LATEX document, which is quite simple, AUC TEX tion of lisp called Emacs-lisp. Just as TEX allows can help a user perform certain tasks. The following you to associate functionality to a token, Emacs lets is an outline of the major features of AUC TEX. you bind functionality to the keys of your keyboard. • Insertion of templates for logical-structural When TEX implicitly inserts a \vbox whenever a plain letter is encountered, Emacs implicitly calls compositions such as environments and sec- the function self-insert-command (which simply tions.