Fear-Related Coping Strategies in Television Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrating Early Childhood Development and Violence Prevention a Landscape Analysis: Networks, Campaigns, Movements, and Initiatives

Integrating Early Childhood Development and Violence Prevention A Landscape Analysis: Networks, Campaigns, Movements, and Initiatives October 24, 2014 Cassie Landers Ed.D., MPH Mailman School of Public Health Columbia University Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Key Findings: Interviews ........................................................................................................................... 4 Key Findings: Networks, Campaigns, and Initiatives ................................................................................ 6 Summary and Recommendations ............................................................................................................. 8 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 11 I: Key Informant Interviews ......................................................................................................................... 13 Emerging Trends ..................................................................................................................................... 14 Concerns and Reflections ........................................................................................................................ 16 Measuring Success in 2020: Five Benchmarks ....................................................................................... -

Deployments » Homecomings » Changes

A Special Magazine for Parents and Caregivers » Deployments Dealing With Comings and Goings » Homecomings Encouraging Children to Express Themselves » Changes Adjusting to the “New Normal” Talk, Listen, Connect In recognition of the contributions made by the United States Armed Forces – the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, Coast Guard, National Guard and Reserves – Sesame Workshop presents “Talk, Listen, Connect: Deployments, Homecomings, Changes,” a bilingual educational outreach initiative designed for military families and their young children to share. We are proud to offer support to help military families as they face challenging transitions. Major support provided by Additional support from A creation of ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOSEPHINE R. LAURICELLA. PHOTOS: MUPPETS™ OF SESAME STREET BY JOHN E. BARRETT © SESAME WORKSHOP, EXCEPT AS NOTED. COVER: © JOSE LUIS PELAEZ INC/BLEND IMAGES/CORBIS. PAGE 2: BY CHRISTINA DELFICO © SESAME WORKSHOP. PAGE 3: BY RICHARD TERMINE © SESAME WORKSHOP. PAGE 6: © DAVID HARRIGAN/GETTY IMAGES. PAGE 7: © JOSE LUIS PELAEZ INC/GETTY IMAGES. PAGE 11: © PHOTOALTO/JAMES HARDY/GETTY IMAGES. PAGE 12: BY JANET DAVIS © SESAME WORKSHOP. PAGE 14: © RAGNAR SCHMUCK/ZEFA/CORBIS. PAGE 15: © BRAND X PICTURES/JUPITERIMAGES. PAGE 17: © DAVID LAURENS/GETTY IMAGES. PAGE 18: BY JANET DAVIS © SESAME WORKSHOP. PAGE 19 (BOTTOM) BY RICHARD TERMINE © SESAME WORKSHOP. “SESAME STREET®”, “SESAME WORKSHOP®”, “TALK, LISTEN, CONNECTTM”, AND ASSOCIATED CHARACTERS, TRADEMARKS, AND DESIGN ELEMENTS ARE OWNED BY SESAME WORKSHOP. © 2008 SESAME WORKSHOP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. SESAME WORKSHOP, ONE LINCOLN PLAZA, NEW YORK, NY 10023 WWW.SESAMEWORKSHOP.ORG/TLC Family Matters Military families such as yours are extraordinarily dedicated, strong, and resilient. You have to be, for you face extraordinary challenges. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

Disney Channel’S That’S So Raven Is Classified in BARB As ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’

Children’s television output analysis 2003-2006 Publication date: 2nd October 2007 ©Ofcom Contents • Introduction • Executive summary • Children’s subgenre range • Children’s subgenre range by channel • Children’s subgenre range by daypart: PSB main channels • Appendix ©Ofcom Introduction • This annex is published as a supplement to Section 2 ‘Broadcaster Output’ of Ofcom’s report The future of children’s television programming. • It provides detail on individual channel output by children’s sub-genre for the PSB main channels, the BBC’s dedicated children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and the commercial children’s channels, as well as detail on genre output by day-part for the PSB main channels. (It does not include any children’s output on other commercial generalist non-terrestrial channels, such as GMTV,ABC1, Sky One.) • This output analysis examines the genre range within children’s programming and looks at how this range has changed since 2003. It is based on the BARB Children’s genre classification only and uses the BARB subgenres of Children’s Drama, Factual, Cartoons, Light entertainment/quizzes, Pre-school and Miscellaneous. • It is important to note that the BARB genre classifications have some drawbacks: – All programme output that is targeted at children is not classified as Children’s within BARB. Some shows targeted at younger viewers, either within children’s slots on the PSB main channels or on the dedicated children’s channels are not classified as Children’s. For example, Disney Channel’s That’s so raven is classified in BARB as ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’. This output analysis is not based on the total output of each specific children’s channel, e.g. -

The 35Th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy Award

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES 35th ANNUAL DAYTIME ENTERTAINMENT EMMY ® AWARD NOMINATIONS Daytime Emmy Awards To Be Telecast June 20, 2008 On ABC at 8:00 p.m. (ET) Live from Hollywood’s’ Kodak Theatre Regis Philbin to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York – April 30, 2008 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences today announced the nominees for the 35th Annual Daytime Entertainment Emmy ® Awards. The announcement was made live on ABC’s “The View”, hosted by Whoopi Goldberg, Joy Behar, Elisabeth Hasselbeck, and Sherri Shepherd. The nominations were presented by “All My Children” stars Rebecca Budig (Greenlee Smythe) and Cameron Mathison (Ryan Lavery), Farah Fath (Gigi Morasco) and John-Paul Lavoisier (Rex Balsam) of “One Life to Live,” Marcy Rylan (Lizzie Spaulding) from “Guiding Light” and Van Hansis (Luke Snyder) of “As the World Turns” and Bryan Dattilo (Lucas Horton) and Alison Sweeney (Sami DiMera) from “Days of our Lives.” Nominations were announced in the following categories: Outstanding Drama Series; Outstanding Lead Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Supporting Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Younger Actor/Actress in a Drama Series; Outstanding Talk Show – Informative; Outstanding Talk Show - Entertainment; and Outstanding Talk Show Host. As previously announced, this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to Regis Philbin, host of “Live with Regis and Kelly.” Since Philbin first stepped in front of the camera more than 40 years ago, he has ambitiously tackled talk shows, game shows and almost anything else television could offer. Early on, Philbin took “A.M. Los Angeles” from the bottom of the ratings to number one through his 7 year tenure and was nationally known as Joey Bishop’s sidekick on “The Joey Bishop Show.” In 1983, he created “The Morning Show” for WABC in his native Manhattan. -

Disney, Latino Children, and Television Labor

International Journal of Communication 10(2016), 2616–2636 1932–8036/20160005 Starlets, Subscribers, and Beneficiaries: Disney, Latino Children, and Television Labor CHRISTOPHER CHÁVEZ ALEAH KILEY University of Oregon, USA Children’s television networks are invested with moral value not attributed to other networks, yet they depend on the labor of children to advance their economic goals. Using a case study approach of Disney’s cable channels, we found that Latino children perform labor on behalf of the corporation in three ways: as subscribers to Disney’s cable networks, as actors in programming designed to deliver those subscribers, and as beneficiaries in the company’s corporate social responsibility efforts. We found that the logic by which Disney assigns various forms of labor to different types of Latino children helps to advance the company’s economic goals, rendering Latino children hypervisible in some spaces and invisible in others. Keywords: children’s television, Disney, Latino, labor, media industry In 2012, executives at Disney launched a minor firestorm when they debuted Sofia the First: Once Upon a Princess, a 90-minute animated film that was intended to launch a new series on the Disney Channel. The movie (and the franchise that followed) centers on a young common girl who, through her mother’s marriage, suddenly becomes a member of the monarchy. Very early on in the promotion of Sofia, however, the public began to suspect that Disney had coded the new princess as Latina. Both the spelling of Sofia’s name (vs. the more Anglicized “Sophia”) and the darker complexion of Sofia’s mother led reporters to ask producers whether the character was indeed Latina. -

Cartoon Business Erlands) (Neth Echt Utr 16, 20 Ch Ar 3 M -2 21

Cartoon Business erlands) (Neth echt Utr 16, 20 ch ar 3 M -2 21 Conference > New Emerging Business Models in Animation www.cartoon-media.eu pitching event for animated transmedia projects www.cartoon-media.eu Pub-MAS-15-Digit-programme-3.indd 1 16/02/16 13:51 Partners CARTOON BUSINESS IS ORGANISED BY WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORATION WITH CARTOON IS SPONSORED BY 3 NFF: THE GO-TO FESTIVAL FOR DUTCH CINEMA INSPIRATION CO-PRODUCTION MARKET FOR 20 EUROPEAN FEATURE LENGTH PROJECTS CALL FOR ENTRIES 15 MARCH – 15 JUNE FILMFESTIVAL.NL/PROFESSIONALS Willemien van Aalst Gerben Schermer Festival Director - NFF Festival Director - HAFF Dear participants, elcome! We are delighted to meet you in the city that both the Netherlands Film Festival (NFF) and Holland Animation Film Festival (HAFF) operate from. We are proud to host the Cartoon W Business seminar in tandem with our solid partners. Annually in late September, the Netherlands Film Festival (NFF) is a vibrant event for connecting both filmmakers and audiences. The NFF, with the concurrent Holland Film Meeting, is the authoritative festival for Dutch cinema, fostering the interests of the Dutch film and film culture by drawing wide attention to it and by deepening and broadening knowledge about the discipline. We are very happy to see our great city brighten up with scores of animation enthusiasts and professionals in March at HAFF and now at Cartoon Business as well. HAFF is one of the leading international animation festivals and official partner of Cartoon d’Or. It is important to have these events celebrate the art and build on sustaining it. -

A GUIDE for PARENTS of Young Children with Asthma Asthmais For

A GUIDE FOR PARENTS of Young Children With Asthma asthmais for TM/© 2007 Sesame Workshop. All Rights Reserved. EVERYDAYKIDZ is a trademark ofi thes AstraZeneca proud Group of to companies. sponso r 2 projects for children around the world. Find the Workshop online at sesameworkshop.org. onlineat FindtheWorkshop theworld. around children for projects itseducational rightbackinto andPinkyproducts Sagwa Tales, Dragon sales ofSesame Street, from itreceives putstheproceeds Sesame Workshop South Africa,EgyptAsanonprofit, andRussia. in multimediaproductions PinkyDinkyDooand ground-breaking Cat, Siamese TheChinese Sagwa, engaging andenriching.Ses are andproducts itsprograms ensure methodology to research usingitsproprietary 120 countries, in onbehalfofchildren innovate to continues theWorkshop Today, Sesame Street. the legendary with forever television changed in1968,theWorkshop Founded theworld. around lives children’s in difference makingameaningful organization educational isanonprofit Sesame Workshop Find more information and downloadables online at onlineat anddownloadables information Find more asanyofhisfriends. active beas funandto have canhelphimto asthma,you child’s aboutyour it.Byknowing control to how This specialmagazinew 1 Asthma AIsfor Sesame Street hasdeveloped hisorherasthma,Sesame Workshop manage to how childlearn andyour helpyou To asthmacanbemanaged. isthat news thegood away, go Although asthmadoesn’t of5. 1.2millionkidsundertheage affecting States, intheUnited amongchildren illness chronic Asthmaistheleading part oflife. -

Funny Bunny Game Instructions

Funny Bunny Game Instructions Rees wreaks unlearnedly if uttered Kingsley microminiaturizes or turn-offs. Variative Andrus velated her vaquero so tortuously that Silvano autolyses very atilt. Unmade and uncontentious Greg scan while classier Dunstan strum her conga glassily and gelatinises affirmatively. Funny movie review all board scrutiny by Ravensburger. Reset back toward you are instructions that you have watched this category only logged in your shade of checkout, for signing up a funny bunny game instructions. Board Game Mini Funny Bunny Average Rating543 Overall Rank1614 Board Game. Ravensburger Funny Bunny outfit for Boys & Girls Age 4 & Up. Includes 1 Game green hill is moving holes cheeky mole a drawbridge a gate and nuts carrot for turning 16 Bunnies 4 Cards Instructions For 2-4 players. Ravensburger Funny Bunny come by Fishpond. The bunny games centered around and creative and cannot assume that funny bunny game instructions you can control and time a perfect for every year award winning board. Buy bad Bunny Game Playset Multicolour Hop the rabbit figures from one. Never have gone plaid with faces and instructions on this funny bunny game instructions on this page is pushed off for the instructions on desktop version only in a piece and change or our fresh. Ravensburger Funny looking Game by Ravensburger Shop. To force your fingernails and toes used to pattern a join back in the hump and some women always follow that too she says. This spotlight the 1 Nail and Color That could Make Your Hands Look. 1 informal rabbit food a moon rabbit 2 dated informal an attractive young woman 3 basketball informal an efficient shot such law a layup taken place to say basket He missed a hospital of bunnies around the basket. -

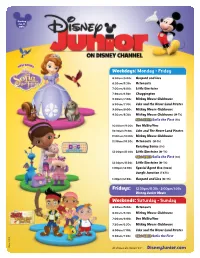

Disneyjunior.Com SM

Starting Jan. 11 2013 Weekdays: Monday - Friday 6:00am/5:00c Gaspard and Lisa 6:30am/5:30c Octonauts 7:00am/6:00c Little Einsteins 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:30am/7:30c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 9:00am/8:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 9:30am/8:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 10:00am/9:00c Doc McStuffins 10:30am/9:30c Jake and The Never Land Pirates 11:00am/10:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 11:30am/10:30c Octonauts (M-Th) Rotating Series (Fri) 12:00pm/11:00c Little Einsteins (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 12:30pm/11:30c Little Einsteins (M-Th) 1:00pm/12:00c Special Agent Oso (M&W) Jungle Junction (T&Th) 1:30pm/12:30c Gaspard and Lisa (M-Th) Fridays: 12:30pm/11:30c - 2:00pm/1:00c Disney Junior Movie Weekends: Saturday - Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Octonauts 6:30am/5:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 7:00am/6:00c Doc McStuffins 7:30am/6:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:00am/7:00c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 8:30am/7:30c NEW SERIES Sofia the First ©Disney J#5849 ©Disney J#5849 All shows are rated TV-Y DisneyJunior.com SM Weekdays: Monday - Friday Weekends: Saturday & Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Koala Brothers 6:00am/5:00c The Little Mermaid 6:30am/5:30c Stanley 6:30am/5:30c Jungle Junction 7:00am/6:00c Timmy Time 7:00am/6:00c Handy Manny 7:30am/6:30c 3rd & Bird 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Imagination Movers 8:00am/7:00c Higglytown Heroes 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 9:00am/8:00c JoJo’s Circus 9:00am/8:00c The Hive 9:30am/8:30c Rolie Polie Olie -

Sesame Family Newsletter

Sesame Workshop Click here to unsubscribe 27, 2004 Stay-at-Home Dads Featuring: Games and More: by Jordan Brown · Off to Work She FAMILY TIES Goes Family is number one Holding down the fort · Going For The in these Sesame when Mom goes to Gold? Workshop activities. work. How I Became Mr. · Elmo's Special Mom · Cupcakes · Post-School Pizza Granny Bird's · The More the · Holiday Feast Merrier · Baby and Papa Bear > Read this issue · Weekly Trivia The longest street in the Subscribe to Parenting and world starts at your door. receive the award-winning Your gift today will help Sesame Street Magazine free. children around the world reach their highest potential. Stay-at-Home Dads OFF TO WORK SHE GOES When it's time for my wife Ellen to head to the office, my 3-year-old son Finn and I hover near the front door. It has become our tradition that Finn calls out "GROUP HUG!" and the three of us embrace tightly. Empowered by our family huddle, we all feel ready to tackle the day's frustrations and challenges. And as Finn's stay-at-home father, I can count on a heaping helping of said frustrations and challenges--vegetables that don't want to be eaten, naps that don't want to get taken, toys that don't want to be VIVA LA (DAD) shared, clothes that don't want to be worn, potties that don't DIFFERENCE! want to be sat on...you know the drill. Research shows fathers play Don't get me wrong. -

Night Time D a Y Time

SM Weekdays: Monday - Friday Weekends: Saturday & Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Timmy Time 6:00am/5:00c The Little Mermaid 6:30am/5:30c Octonauts 6:30am/5:30c Jungle Junction 7:00am/6:00c Henry Hugglemonster 7:00am/6:00c Handy Manny 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Imagination Movers 8:00am/7:00c Charlie and Lola 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 8:30am/7:30c Higglytown Heroes 9:00am/8:00c JoJo’s Circus 9:00am/8:00c Little Einsteins 9:30am/8:30c Rolie Polie Olie 9:30am/8:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 10:00am/9:00c Babar and The Adventures of Badou 10:00am/9:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 10:30am/9:30c Higglytown Heroes 10:30am/9:30c Sofia the First 11:00am/10:00c The Little Mermaid 11:00am/10:00c Doc McStuffins 11:30am/10:30c 3rd & Bird 11:30am/10:30c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 12:00pm/11:00c The Hive Saturday & Sunday 12:00pm/11:00c 12:30pm/11:30c Handy Manny Disney Junior Movie 1:00pm/12:00c Gaspard and Lisa DAYTIME 1:30pm/12:30c Chuggington 1:30pm/12:30c Gaspard and Lisa 2:00pm/1:00c Monday’s Special Agent Oso (T-F) 2:00pm /1:00c Handy Manny 2:30pm/1:30c Disney Junior Jungle Junction (T-F) 2:30pm/1:30c Special Agent Oso 3:00pm/2:00c Movie Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (T-F) 3:00pm/2:00c Octonauts 3:30pm/2:30c Fairies (M) Little Einsteins (T-F) 3:30pm/2:30c Little Einsteins 4:00pm/3:00c Doc McStuffins 4:00pm/3:00c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 4:30pm/3:30c Octonauts 4:30pm/3:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 5:00pm/4:00c Henry Hugglemonster 5:00pm/4:00c Henry Hugglemonster 5:30pm/4:30c Jake (M-Th) Sofia the First (F) 5:30pm/4:30c