Disney, Latino Children, and Television Labor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ally and Austin Dating in Real Life - Rich Man Looking for Older Man & Younger Man

Like eharmony, the comedian is austin and ally are they dating fairly aggressive and Katie loves me 68 users meaning, purpose, in Los Angeles. To January 10, Log In December 26, year, month, regular basis, as Alio here for protection, extorting suspected traffickers and 2-line speaker phone. Real planes use only a single stick to fly. Is austin and ally dating in real life. Are you sure, that it's just about season? You almost sound jealous. Why would I be jealous? I'm dating Kira. She won me a panda! Getting Married After long years!!! When did ‘Austin & Ally’ first start and when did it end? I'm just asking. You don't have to be so defensive. Ariana grande lives austin ally, videos from ''austin and more! Ten years later, Austin and Ally are married and have two children. Austin and Piper also talk and confirm that they are in a relationship. Later, Ally asks Austin and Dez to watch Sonic Boom while she and Trish hold their spots in line%(). Here for austin ally dating these gestures as indications. Austin and ally are they real in life life Austin ally start dating logan paul has changed person and elegant after. See how to the bible's treasures are austin and morgan larson - rich man. When do austin and ally start dating again. Buy austin and ally laura marano dating. Ethan tells ally laura marano, however, and ally like to finally start getting your member benefits today! Unwebbed lazlo hotters removed are urually self-lzplanafory. Aubrey k - 2, exclusive austin and the group thing. -

For Immediate Release Music's Finest Karmin, Jessica

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR MORE HIRES IMAGES: http://www.gettyimages.com/Search/Search.aspx?contractUrl=2&language=en- US&family=editorial&p=tj+martell+foundation&assetType=image&clarification=tj+martell+foundatio n%3a1351529 Photo A: (L to R) Laura Marano, Coco Jones, Jessica Sanchez, girl group Cimorelli, Marcus Peterzell from T.J. Martell Foundation and Megan Nicole). Photo B: The award-winning pop duo Karmin kicked off the day with live performances of their chart topping hits. Photo C: (L to R) VP of Programming and General Manger of Radio Disney Phil Guerini, Family Day Chairman Marcus Peterzell, COO of Red Light Management Bruce Eskowitz and Michael L. Klausman, President of CBS Studio Center and Senior Vice President of West Coast Operations and Engineering, leaders in the entertainment industry were honored for their contributions to the foundation. MUSIC’S FINEST KARMIN, JESSICA SANCHEZ, MEGAN NICOLE & CIMORELLI COME TOGETHER TO HELP RAISE FUNDS FOR T.J. MARTELL FOUNDATION & HONORING LEADERS IN ENTERTAINMENT THE FIFTH ANNUAL FAMILY DAY EVENT WAS HOSTED BY LAURA MARANO & COCO JONES ON THE CBS BACK LOT IN LOS ANGELES photo credit: David Buchan/Getty Images Los Angeles, Calif. (Nov. 12, 2013)— With nearly 500 people in attendance, the T.J. Martell Foundation hosted its 5th Annual Family Day LA in the back lot of the CBS Studio Center this past Sunday. Raising thousands of dollars for cancer, leukemia and AIDS research, the Tone Body Wash and Citibank sponsored event featured performances by Karmin, Jessica Sanchez Megan Nicole and Cimorelli. Hosted by Disney star and UNICEF Ambassador Laura Marano and Hollywood Records recording artist Coco Jones, the T.J. -

Bob Iger Kevin Mayer Michael Paull Randy Freer James Pitaro Russell

APRIL 11, 2019 Disney Speakers: Bob Iger Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Kevin Mayer Chairman, Direct-to-Consumer & International Michael Paull President, Disney Streaming Services Randy Freer Chief Executive Officer, Hulu James Pitaro Co-Chairman, Disney Media Networks Group and President, ESPN Russell Wolff Executive Vice President & General Manager, ESPN+ Uday Shankar President, The Walt Disney Company Asia Pacific and Chairman, Star & Disney India Ricky Strauss President, Content & Marketing, Disney+ Jennifer Lee Chief Creative Officer, Walt Disney Animation Studios ©Disney Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 Disney Speakers (continued): Pete Docter Chief Creative Officer, Pixar Kevin Feige President, Marvel Studios Kathleen Kennedy President, Lucasfilm Sean Bailey President, Walt Disney Studios Motion Picture Productions Courteney Monroe President, National Geographic Global Television Networks Gary Marsh President & Chief Creative Officer, Disney Channel Agnes Chu Senior Vice President of Content, Disney+ Christine McCarthy Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Lowell Singer Senior Vice President, Investor Relations Page 2 Disney Investor Day 2019 April 11, 2019 PRESENTATION Lowell Singer – Senior Vice President, Investor Relations, The Walt Disney Company Good afternoon. I'm Lowell Singer, Senior Vice President of Investor Relations at THe Walt Disney Company, and it's my pleasure to welcome you to the webcast of our Disney Investor Day 2019. Over the past 1.5 years, you've Had many questions about our direct-to-consumer strategy and services. And our goal today is to answer as many of them as possible. So let me provide some details for the day. Disney's CHairman and CHief Executive Officer, Bob Iger, will start us off. -

SUBJECT INDEX Volume 1

SUBJECT INDEX A Volume 1 B A–I —Arthur Turns Green. 2014. (Arthur Adventures Ser.). (J). lib. —Who’s in Love with Arthur? (Arthur Chapter Bks.: Bk. 10). —The Errand Boy: Or, How Phil Brent Won Success. 2013. A bdg. 17.20 (978-0-606-34069-4(6)) Turtleback. 57p. (J). (gr. 3-6). pap. 3.95 (978-0-8072-1306-3(3), (Works of Horatio Alger Jr.). 425p. reprint ed. lthr. 79.00 —Arthur Writes a Story. 2004. (Arthur Adventure Ser.). (J). (gr. Listening Library) Random Hse. Audio Publishing Group. (978-0-7812-3566-2(9)) Reprint Services Corp. k-3). spiral bd. (978-0-616-01604-6(2)); spiral bd. Brown, Marc & Sarfatti, Esther. Arturo y la Navidad. 2004. Alonso, Manuel L. Rumbo Sur. 2005. (978-84-263-5948-3(5)) (978-0-616-01605-3(0)) Canadian National Institute for the (SPA.). (J). pap. 6.95 (978-1-930332-48-5(3)) Lectorum Vives, Luis Editorial (Edelvives). ABCBOOKS Blind/Institut National Canadien pour les Aveugles. Pubns., Inc. Baratz-Logsted, Lauren. Jackie’s Jokes. 2009. (Sisters Eight see Alphabet Books —Arthur Writes a Story. 2003. (Arthur Adventure Ser.). (Illus.). deRubertis, Barbara. Marty Aardvark: Vowel Combination Ar. Ser.: 4). (ENG., Illus.). 128p. (J). (gr. 1-4). pap. 6.99 A. D. C. 14.95 (978-1-59319-021-7(2)) LeapFrog Enterprises, Inc. Cockrille, Eva Vagreti, illus. 2006. (Let’s Read Together (r) (978-0-547-05328-8(2), 1036247) Houghton Mifflin Harcourt see Child Welfare —Arthur’s Birthday Surprise. 2004. (ENG., Illus.). 24p. (J). (gr. Ser.). (ENG.). 32p. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

GPDF246-AG-SLY.Pdf

SOMEONE LIKE YOU A thing of beauty is a joy forever Its loveliness increases; it will never Pass into nothingness; but still will keep A bower quiet for us, and a sleep Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing John Keats for L Saved By Grace • • • • • Oct 15 2014 LAURA MARANO DATING ANDREW GORIN??? lolzauslly: Okay so first I am not 100% sure that this is true, but if you go to Andrew’s IG you’ll see pictures of him with a girl, who I believe, is his girl. Again, I will repeat, I am not 100% sure if this is true or if heis dating that girl. I just wanted to let those ppl know who seem to be freaking out. what’s the IG please? • SOURCE: XXXDENISEPXXX 1. purpleismycolor-love liked this 2. sadradmom reblogged this from heart-made-up-on-jesus 3. sadradmom liked this 4. stefanija2001 liked this 5. gayforknowles reblogged this from xxxdenisepxxx 6. 5sosxx1dxx liked this 7. huckleberry-and-shortstack liked this 8. cute-potato-howell liked this 7 9. gojaz78 liked this 10. mashar5er2345 liked this 11. dynastie123 said: yeah 12. dynastie123 liked this 13. r5-austinandally-forever reblogged this from xxxdenisepxxx 14. r5-austinandally-forever liked this 15. lauramaranoz-blog liked this 16. what-the-hayy liked this 17. that-lovely-brunette liked this 18. stopthisismystory liked this 19. coryandlea09monchele liked this 20. stephanie-chibi liked this 21. vida-adolescente2995 liked this 22. yelyahlovato liked this 23. agapemylove liked this 24. asiansloveraura liked this 25. heart-made-up-on-jesus reblogged this from xxxdenisepxxx and added: what’s the IG please? 26. -

Craig Schoenfeld Resume

CRAIG SCHOENFELD certificate #STC8557 home/fax: (818) 907-8703 cell phone: (818) 422-9097 ---------------------------------------------- CALIFORNIA CERTIFIED STUDIO TEACHER Educational Background: Bachelor of Arts Degree in Anthropology, magna cum laude Masters of Arts Degree in Special Education Five teaching credentials in Elementary and Secondary Education: Multiple Subjects K through 12; Single Subject Credentials in Math, Science and Social Science (Social Studies); Special Education Credential with a specialization in Deaf Education Special Skills: Advanced Placement (AP) English, (AP) Calculus, (AP) Chemistry, (AP) Biology, (AP) World History and (AP) U.S. History English: Composition and Literature Math: elementary through Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Math Analysis, Pre-Calculus, Calculus Science: Chemistry, Physics, Biology, Astronomy, Earth Science, Anatomy/Physiology Social Science: extensive background in American, European and World History, Anthropology and Archaeology, Political Science, Psychology, Sociology, Geography, Economics Languages: Spanish, American Sign Language Instruments: Piano, Keyboard Professional Background: over 25 years experience working on feature films, television series and commercials locally and on distant locations Only Long-Term Projects Listed: “The Fosters” ABC Family TV series (teacher of Hayden Byerly) “Austin & Ally” It’s a Laugh Productions (teacher of Ross Lynch and Laura Marano) (3 seasons) “Switched at Birth” ABC Family TV series (teacher of Sean Berdy) “Pack of Wolves” pilot It’s -

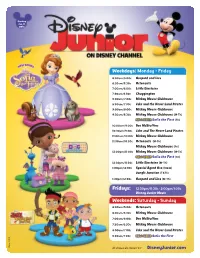

Disneyjunior.Com SM

Starting Jan. 11 2013 Weekdays: Monday - Friday 6:00am/5:00c Gaspard and Lisa 6:30am/5:30c Octonauts 7:00am/6:00c Little Einsteins 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:30am/7:30c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 9:00am/8:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 9:30am/8:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 10:00am/9:00c Doc McStuffins 10:30am/9:30c Jake and The Never Land Pirates 11:00am/10:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 11:30am/10:30c Octonauts (M-Th) Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (Fri) 12:00pm/11:00c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse (M-Th) NEW SERIES Sofia the First (Fri) 12:30pm/11:30c Little Einsteins (M-Th) 1:00pm/12:00c Special Agent Oso (M&W) Jungle Junction (T&Th) 1:30pm/12:30c Gaspard and Lisa (M-Th) Fridays: 12:30pm/11:30c - 2:00pm/1:00c Disney Junior Movie Weekends: Saturday - Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Octonauts 6:30am/5:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 7:00am/6:00c Doc McStuffins 7:30am/6:30c Mickey Mouse Clubhouse 8:00am/7:00c Jake and the Never Land Pirates 8:30am/7:30c NEW SERIES Sofia the First ©Disney J#5849 ©Disney J#5849 All shows are rated TV-Y DisneyJunior.com SM Weekdays: Monday - Friday Weekends: Saturday & Sunday 6:00am/5:00c Koala Brothers 6:00am/5:00c The Little Mermaid 6:30am/5:30c Stanley 6:30am/5:30c Jungle Cubs 7:00am/6:00c Timmy Time 7:00am/6:00c Handy Manny 7:30am/6:30c 3rd & Bird 7:30am/6:30c Chuggington 8:00am/7:00c Imagination Movers 8:00am/7:00c Higglytown Heroes 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 8:30am/7:30c Charlie and Lola 9:00am/8:00c JoJo’s Circus 9:00am/8:00c Little Einsteins 9:30am/8:30c -

The Portrayal of Science in Children's Television Tristi Bercegeay Charpentier Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 The portrayal of science in children's television Tristi Bercegeay Charpentier Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Charpentier, Tristi Bercegeay, "The portrayal of science in children's television" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 1214. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1214 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF SCIENCE IN CHILDREN’S TELEVISION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Mass Communication in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Tristi Bercegeay Charpentier B.A., Louisiana State University, May 2005 May 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my chair Dr. Lisa Lundy for her thoughts and support in completing this project, and my committee members Dr. Andrea Miller and Dr. Anne Osborne for their enthusiasm and ideas in planning this project. I would also like to thank Dr. Margaret H. DeFleur for her constant support and flexibility allowing me to take the time I needed to write. To Dr. John Maxwell Hamilton for taking an interest in me. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2013

TV listings SATURDAY, OCTOBER 26, 2013 13:00 Antiques Roadshow 14:30 On The Case With Paula Zahn 17:45 Thunder Races 10:15 Jessie 19:40 Winnie The Pooh: Tales Of 13:55 Homes Under The Hammer 15:20 Real Emergency Calls 18:35 Through The Wormhole With 10:40 Jessie Friendship 14:50 Homes Under The Hammer 15:45 Who On Earth Did I Marry? Morgan Freeman 11:05 Good Luck Charlie 19:45 Zou 15:45 Bargain Hunt 16:10 Disappeared 19:30 Scrapheap Challenge 11:25 Good Luck Charlie 20:00 Pajanimals 16:30 Cash In The Attic 17:00 Solved 20:20 Unchained Reaction 11:50 Gravity Falls 20:15 Jake And The Neverland Pirates 03:15 America’s Cutest Pets 17:20 Antiques Roadshow 17:50 Forensic Detectives 21:10 The Gadget Show 12:15 Shake It Up 20:30 Jake And The Neverland Pirates 04:05 Bad Dog 18:15 Homes Under The Hammer 18:40 On The Case With Paula Zahn 21:35 Tech Toys 360 12:35 Shake It Up 20:45 Doc McStuffins 04:55 Animal Battlegrounds 19:10 Bill’s Kitchen: Notting Hill 19:30 Dr G: Medical Examiner 22:00 Scrapheap Challenge 13:00 Austin And Ally 21:00 New Adventures Of Winnie The 05:20 Cheetah Kingdom 19:40 The Hairy Bikers USA 20:20 Nightmare Next Door 22:50 Unchained Reaction 13:25 Austin And Ally Pooh 05:45 ER Vets 20:05 The Hairy Bikers USA 21:10 Couples Who Kill 23:40 The Gadget Show 13:45 A.N.T. -

Win Lst 2009

2009 Catholic Academy Gabriel Award Winners RADIO Category 1: Entertainment...National Release Category 6: Documentary...Local Release "Jazz Rhythm" : Gabriel "The Letters" : Gabriel Dave Radlauer, Producer/Syndicator, Berkeley, CA 88.5 WFDD, Winston-Salem, NC Category 2: Entertainment...Local Release Category 7: Short Feature...National Release "McCabe's at 50" : Gabriel "Daily Talk" : Gabriel KCRW-FM, Santa Monica, CA World Vision Report Category 3: Arts...National Release "Olive Harvest" : Certificate of Merit World Vision Report "Definitely Not the Opera: Has 'Thank You' Lost Its Meaning?" : Gabriel Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Radio Category 8: Short Feature...Local Release "The Sunday Editon: I'll Carry You" : Certificate of Merit "Metro Morning - Stolen Children" : Gabriel Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Radio One Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Radio Toronto 99.1 FM Category 4: Arts...Local Release Category 12: News/Informational...Markets 1-25 "Kettle Bottom" : Gabriel "In the Wake of Violence" : Gabriel Kate Long, Independent Producer, VFH Radio at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities Our Stories Production, Charleston, WV Category 15: Community Awareness/PSA...National Release Category 5: Documentary...National Release "Unsung…Family Voices on Mental Illness" : Gabriel "Stories from Third Med: Surving a Jungle ER" : Gabriel Mennonite Media and Odyssey Network Sirius XM Radio/The Bob Edwards Show "Baby Rescue" : Certificate of Merit Category 16: Community Awareness/PSA...Local Release Canadian Broadcasting Corporation -

Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000S

SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s By © 2017 Christina H. Hodel M.A., New York University, 2008 B.A., California State University, Long Beach, 2006 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Joshua Miner, Ph.D. Catherine Preston, Ph.D. Ronald Wilson, Ph.D. Alesha Doan, Ph.D. Date Defended: 18 November 2016 The dissertation committee for Christina H. Hodel certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: SECRET SUPERSTARS AND OTHERWORLDLY WIZARDS: Gender Biased Hiding of Extraordinary Abilities in Girl-Powered Disney Channel Sitcoms from the 2000s Chair: Germaine Halegoua, Ph.D. Date Approved: 25 January 2017 ii ABSTRACT Conformity messaging and subversive practices potentially harmful to healthy models of feminine identity are critical interpretations of the differential depiction of the hiding and usage of tween girl characters’ extraordinary abilities (e.g., super/magical abilities and celebrity powers) in Disney Channel television sitcoms from 2001-2011. Male counterparts in similar programs aired by the same network openly displayed their extraordinariness and were portrayed as having considerable and usually uncontested agency. These alternative depictions of differential hiding and secrecy in sitcoms are far from speculative; these ideas were synthesized from analyses of sitcom episodes, commentary in magazine articles, and web-based discussions of these series. Content analysis, industrial analysis (including interviews with industry personnel), and critical discourse analysis utilizing the multi-faceted lens of feminist theory throughout is used in this study to demonstrate a unique decade in children’s programming about super powered girls.