D-Signed for Girls: Disney Channel and Tween Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

Bloomington(KHS) Overall Score Reports

Bloomington(KHS) Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance Platinum 1st Place 1 797 Funky Y2C - Metro Dance Center - Shoreview, MN 82.9 Alyssa Jacobs Platinum 1st Place 2 157 Amazing Mayzie - Spirit of Dance - Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada P7B 3C1, CN 81.8 Avery Marshall Gold 1st Place 3 161 Hands - Spirit of Dance - Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada P7B 3C1, CN 81.4 Tia Kiiskila Gold 1st Place 4 91 Shake It Up - Nicole's School of Dance - La Crescent, MN 80.2 Riley Wiczek Gold 1st Place 4 159 Footloose - Spirit of Dance - Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada P7B 3C1, CN 80.2 Hannah Donylyk Advanced Platinum 1st Place 1 409 My Boyfriend's Back - The Dance Connection - Rosemount, MN 82.8 Mercedes Lorentz Platinum 1st Place 2 412 Dimples - The Dance Connection - Rosemount, MN 81.9 Kailey Tomzak Gold 1st Place 3 411 True Colors - The Dance Connection - Rosemount, MN 81.5 Sydney McDonald Competitive Crystal Award 1 782 I Just Wanna Dance - Larkin Dance Studio - Maplewood, MN 86.2 Ava Wagner Platinum 1st Place 2 238 It's My Party - Eleve PAC - Bloomington, MN 83.4 Jenna Raymond Platinum 1st Place 3 786 A Star Is Born - Larkin Dance Studio - Maplewood, MN 82.9 Grace Albrecht Platinum 1st Place 4 237 Let's Dance - Eleve PAC - Bloomington, MN 82.8 Olivia DeAngelo Gold 1st Place 5 17 Aisy Waisy - Studio 4 Dancers - Burnsville, MN 81.8 Helaina Dahlhauser Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Duet/Trio Performance Gold 1st Place 1 158 Fourth of July - Spirit of Dance - Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada P7B 3C1, CN 81.4 Lauren McCourt, Emma Petryna Gold 1st Place -

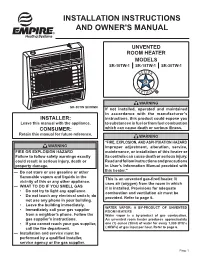

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Nasty Gal Offices to Remain Open in Los Angeles

NEWSPAPER 2ND CLASS $2.99 VOLUME 73, NUMBER 10 MARCH 3–9, 2017 THE VOICE OF THE INDUSTRY FOR 72 YEARS BCBGMaxAzria Files for Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Protection By Deborah Belgum Senior Editor BCBGMaxAzriaGroup, the decades-old Los Angeles apparel company that was one of the first on the contempo- rary fashion scene, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protec- tion in papers submitted Feb. 28 to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. The company’s Canadian affiliate is beginning a sepa- rate filing for voluntary reorganization proceedings under Canada’s Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act. Steps are being taken to close its freestanding stores in Canada and consoli- date its operations in Europe and Japan. The apparel venture, founded in 1989 by Max Azria, has been navigating through some tough financial waters in the past few years. New executives have been unable to turn the company around fast enough and now hope to finish the bankruptcy process in six months. ➥ BCBG page 9 Mitchell & Ness’ booth at the Agenda trade show in Las Vegas TRADE SHOW REPORT Sports Apparel Maker Mitchell & Ness Moving to Irvine Crowded Trade Show By Andrew Asch Retail Editor Schedule Cuts Into LA The North American licensed sportswear business is esti- tive officer. mated to be a multi-billion-dollar market, and Philadelphia- “This facility will house all of our product under one roof Textile Traffic headquartered brand Mitchell & Ness is making a gambit for and modernize our operations with the goal of providing a bigger chunk of it. It is scheduled to open its first West Coast gold-standard customer service. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Taylor Dayne Supermodel Download

Taylor dayne supermodel download Taylor Dayne Supermodel. Now Playing. Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB. Hymn. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor Dayne. MB · Supermodel. Artist: Taylor. Artist: Taylor Dayne. test. ru MB. Supermodel Free Mp3 Download Free RuPaul Supermodel You Better Work mp3. Kbps MB Free Taylor Dayne Supermodel. Taylor Dayne Supermodel mp3 high quality download at MusicEel. Choose from several source of music. Download Supermodel Taylor Dayne mp3 songs in. "Taylor Dayne - Supermodel" Music Lyrics. You better You better work! [covergirl]Work it girl! [give a twirl]Do your thing on the ! Stream Taylor Dayne - Supermodel Jack Smith Edit by Jack Smith from desktop or your mobile device. Listen to songs and albums by Taylor Dayne, including "Tell It to My Heart", of RuPaul's "Supermodel" for The Lizzie McGuire Movie -- acting kept her away. Watch the video, get the download or listen to Taylor Dayne – Supermodel for free. Supermodel appears on the album The Lizzie McGuire Movie. Discover more. Check out RuPaul. SuperModel (You Better Work) ReMixes from RuCo, Inc. on Beatport. Supermodel performed by Taylor Dayne taken from the Lizzie McGuire Motion Picture Soundtrack starring. Tags: Taylor Dayne Supermodel (You Better Work) Fashion Singing lyrics lyric with super model lizzie mcguire movie track hilary duff Full music Song Album. Supermodel - Taylor Dayne. What Dreams Are Made Of - Lizzie McGuire. On An Evening In Roma - Dean Martin. Girl In The Band - Haylie Duff. Floor On Fire written by Taylor Dayne, Niclas Kings, Ivar Lisinski & Tania Download now on iTunes: http. Taylor Dayne, Soundtrack: Win a Date with Tad Hamilton!. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

JULIANNE “JUJU” WATERS Choreographer

JULIANNE “JUJU” WATERS Choreographer COMMERCIAL CHOREOGRAPHY EXPENSIFY // Expensify This // Dir: Andreas Nilsson KLARNA // The Coronation of Smooth Dogg // Dir: Traktor Frontier // Dream Job // Dir: The Perlorian Wish // Amazing Things // Dir: Filip Engstrom Vitamin Water // Drink Outside the Lines // Dir: Traktor Old Navy // Holiyay, Rockstar Jeans // Dir: Joel Kefali Money Supermarket // Bootylicious // Dir: Fredrik Bond LG // Jason Stathum // Dir: Fredrik Bond Dannon // Stayin Alive // Dir: Fredrik Bond Ritz // Putting on the Ritz // Dir: Fredrik Bond FILM Bring It On Cinco // Dir:Billy Woodruff American Carol // Dir: David Zucker Spring Breakdown // Dir: Ryan Shiraki A Cinderella Story// Dir: M. Rosman Bring It On Again // Dir: D. Santostafano TELEVISION Super Bowl XXXVIII // JANET JACKSON feat. JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE Super Bowl XLV // THE BLACK EYED PEAS feat. USHER Fashion Rocks // “Candyman” // CHRISTINA AGUILERA Good Morning America // “Touch my Body” & “That Chick” // MARIAH CAREY Good Morning America // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Soul Train Awards // "I Like The Way You Move" // OUTKAST feat. SLEEPY BROWN Dancing with the Stars // KYLIE MINOGUE Dancing with the Stars // FATIMA ROBINSON TRIBUTE American Music Awards // 2009, 2010, 2011 // THE BLACK EYED PEAS American Music Awards // “Better in Time” // LEONA LEWIS American Music Awards // “Fergalicious” // FERGIE American Music Awards // "Lights, Camera, Action" // P DIDDY feat. MR. CHEEKS & SNOOP DOGG Teen Choice Awards // "Promiscuous" // NELLY FURTATO feat. TIMBERLAND Teen Nick // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Billboard Music Awards // “Fergilicious” // FERGIE VH1 Big in ’06 // “London Bridge & Fergilicious” // FERGIE VIBE Music Awards // “This is How We Do” // THE GAME & 50 CENT Ellen Show // Special Birthday Performance // ELLEN DEGENERES Ellen Show // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Jay Leno // “With Love” // HILARY DUFF Jay Leno // "She Bangs" // WILLIAM HUNG Jimmey Kimmel // “With Love & Stranger” // HILARY DUFF BET Awards // “Come Watch Me” // JILL SCOTT feat. -

THES-Times-Compresse

TRAVIS HEIGHTS GRADE 5 NEWSPAPER December 20, 2016 A1 Headliners Life-Saving Robots THES Student survey T.H.E.S.TIMES Pterosaur Fossil Discovery LITTERING ON CAMPUS A PROBLEM A LITTLE INFO ON TRUMP By: Cosmo Yonnone Donald trump had a T.V. show called “The Apprentice.” He starred in the movie Home Alone. He has 5 children. Trump has 3.7 billon dollars and also refuses to release his taxes. When By: Mireya Gonzalez Trump won, a big percentage of people in the United States wanted to move to a Litter is a big problem for the school. Candy wrappers, paper, chip different country. Trump has claimed bags etc. are found on the campus. Staff member, Mrs. Guerra finds aliens voted for Hillary. it very disrespectful that students are littering. This could possibly mean more work for custodians. Students don’t realize that their actions do affect those around them. If students do their part in keeping the campus clean, they can improve the world a little at a THE CREATION OF THE time. T.H.E.S. SONG By: Yazmin Villanueva Hey, do you know how the Travis TEACHER TREATS TRUMP CLAIMS ALIENS Heights song was made? Well, I do. I By: Thomas Grayson VOTED FOR HILLARY will explain to you how it was made. One day, a 3rd grade teacher named Our purpose was to ask different By: Marissa Rocha Ms. Kyle was teaching her 3rd grade T.H.E.S teachers what their class a little song that Ms. Kyle put favorite treat was, so we asked Hillary won the popular vote in the them and recorded the data in our together. -

Disney Letar Ny Stjärna I Sverige

Disney letar ny stjärna i Sverige I höst är det premiär för ungdomsserien Violetta på Disney Channel i Sverige. Tv-serien har på kort tid etablerat sig som ett ungdomsfenomen på flera internationella marknader där programmets musik spelas flitigt även utanför tv-rutan. Inför premiären i Sverige söker Disney nu tillsammans med Universal MusiC oCh Spinnup en lokal talang för att spela in seriens svenska ledmotiv. Tv-serien Violetta följer huvudpersonen med samma namn i allt det som hör tonårstiden till; kompisar, kärlek, familj och drömmar om framtiden. En stor del av historien utspelar sig på den sång- och dansskola som ’Violetta’ går på och musik är en integrerad del i berättelsen där varje avsnitt innehåller flera specialskrivna låtar. - Det känns fantastiskt roligt att Violetta snart kommer hit. Efter succéerna med Hannah Montana och High School Musical har vi väntat på nästa serie med lika stor potential och att döma av vad vi sett på andra marknader har vi nu det i Violetta. I ett sådant sammanhang känns det extra kul att kunna vidareutveckla vårt samarbete med Universal Music för att hitta rätt sångtalang, säger Anna Glanmark, Marknadsdirektör, The Walt Disney Company Nordic. Arbetet med att identifiera rätt talang för det svenska ledmotivet görs i samarbete med Universal Music genom Spinnup som är en digital distributionstjänst för osignade artister. Det som gör Spinnup unikt är att de osignade artisterna som distribuerar sin musik via tjänsten har tillgång till ett dedikerat team av Spinnup Scouter som söker nya talanger att jobba med, nu även med fokus att hitta Disneys nya stjärna. -

Derrick Harvin Keyboardist/Contemporary Jazz Press Kit

DERRICK HARVIN KEYBOARDIST/CONTEMPORARY JAZZ PRESS KIT Booking: [email protected] VISIT THE OFFICIAL DERRICK HARVIN WEBSITE Email: [email protected] DERRICKHARVIN.COM Contact: 917.830.7653 BIOGRAPHY DERRICK HARVIN Where do we go from here? Living in the present, we ceaselessly search for directions to our future in moments from the past. For Derrick Harvin, the answers of tomorrow may be out of reach, but they can be seen from where he stands. These answers may not always be clear, but Harvin has learned to discover them through hues of color, impressions of imagery, and sounds of emotion. With his debut solo project, From Here, Harvin captures these aspects of the future by creating an artistic journey of self-exploration, sharing a masterpiece that transcends him from a musician to an artist and transforms a past of doubt into a present of hope. Harvin has always found his life’s passion in musical expression, though most of his successes have been achieved behind the scenes. A renowned producer, Harvin has written, produced, and engineered contemporary projects for stars of various genres, including 50 Cent, Hilary Duff, Chaka Khan, Natasha Bedingfield, Betty White, and Kevin Cossom. After graduating from Full Sail University in Orlando, Florida, Harvin produced at Battery Studios in New York, where he gained the attention of Grammy Award-winning producer Vada Nobles and was offered a multi-year publishing deal with Noble’s company, New Ark Entertainment. With this company, Harvin co-wrote and produced Duff’s single, “Stranger,” with American Idol judge Kara DioGuardi, and he also co-produced and engineered additional songs on Duff’s Dignity project.