Competition As Possible Driver of Dietary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paratrechina Longicornis (A) PEST INFORMATION

Paratrechina longicornis Harris, R.; Abbott, K. (A) PEST INFORMATION A1. Classification Family: Formicidae h Subfamily: Formicinae c Tribe: Lasiini esear e R Genus: Paratrechina t , Landcar Species: longicornis of d T har Ric A2. Common names Crazy ant (Smith 1965), long-horned ant, hairy ant (Naumann 1993), higenaga-ameiro-ari (www36), slender crazy ant (Deyrup et al. 2000). A3. Original name Formica longicornis Latreille A4. Synonyms or changes in combination or taxonomy Paratrechina currens Motschoulsky, Formica gracilescens Nylander, Formica vagans Jerdon, Prenolepis longicornis (Latreille) Current subspecies: nominal plus Paratrechina longicornis var. hagemanni Forel A5. General description (worker) Identification Size: monomorphic workers about 2.3–3 mm long. Colour: head, thorax, petiole, and gaster are dark brown to blackish; the body often has faint bluish iridescence. Surface sculpture: head and body mostly with inconspicuous sculpture; appearing smooth and shining. INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT Paratrechina longicornis Whole body has longish setae. Appears quite hairy. Hairs are light in colour grey to whitish. General description: antennae and legs extraordinarily long. Antenna slender, 12-segmented, without a club; scape at least 1.5 times as long as head including closed mandibles. Eyes large, maximum diameter 0.3 times head length; elliptical, strongly convex; placed close to the posterior border of the head. Head elongate; mandibles narrow, each with 5 teeth. Clypeus without longitudinal carinae. Alitrunk slender, dorsum almost straight from anterior portion of pronotum to propodeal dorsum. Metanotal groove slightly incised. Propodeum without spines, posterodorsal border rounded; propodeal spiracles distinct. One node (petiole) present, wedge-shaped, with a broad base, and inclined forward. Dorsal surface of head, alitrunk and gaster with long, coarse, suberect to erect greyish or whitish setae. -

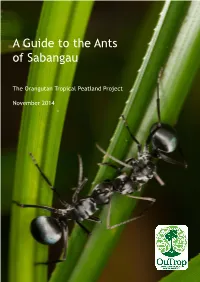

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Digging Deeper Into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning Across Two Continents

diversity Article Digging Deeper into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning across Two Continents Mickal Houadria * and Florian Menzel Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, Hanns-Dieter-Hüsch-Weg 15, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Soil fauna is generally understudied compared to above-ground arthropods, and ants are no exception. Here, we compared a primary and a secondary forest each on two continents using four different sampling methods. Winkler sampling, pitfalls, and four types of above- and below-ground baits (dead, crushed insects; melezitose; living termites; living mealworms/grasshoppers) were applied on four plots (4 × 4 grid points) on each site. Although less diverse than Winkler samples and pitfalls, subterranean baits provided a remarkable ant community. Our baiting system provided a large dataset to systematically quantify strata and dietary specialisation in tropical rainforest ants. Compared to above-ground baits, 10–28% of the species at subterranean baits were overall more common (or unique to) below ground, indicating a fauna that was truly specialised to this stratum. Species turnover was particularly high in the primary forests, both concerning above-ground and subterranean baits and between grid points within a site. This suggests that secondary forests are more impoverished, especially concerning their subterranean fauna. Although subterranean ants rarely displayed specific preferences for a bait type, they were in general more specialised than above-ground ants; this was true for entire communities, but also for the same species if they foraged in both strata. Citation: Houadria, M.; Menzel, F. -

Download PDF File

ISSN 1994-4136 (print) ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Myrmecological News Volume 26 February 2018 Schriftleitung / editors Florian M. STEINER, Herbert ZETTEL & Birgit C. SCHLICK-STEINER Fachredakteure / subject editors Jens DAUBER, Falko P. DRIJFHOUT, Evan ECONOMO, Heike FELDHAAR, Nicholas J. GOTELLI, Heikki O. HELANTERÄ, Daniel J.C. KRONAUER, John S. LAPOLLA, Philip J. LESTER, Timothy A. LINKSVAYER, Alexander S. MIKHEYEV, Ivette PERFECTO, Christian RABELING, Bernhard RONACHER, Helge SCHLÜNS, Chris R. SMITH, Andrew V. SUAREZ Wissenschaftliche Beratung / editorial advisory board Barry BOLTON, Jacobus J. BOOMSMA, Alfred BUSCHINGER, Daniel CHERIX, Jacques H.C. DELABIE, Katsuyuki EGUCHI, Xavier ESPADALER, Bert HÖLLDOBLER, Ajay NARENDRA, Zhanna REZNIKOVA, Michael J. SAMWAYS, Bernhard SEIFERT, Philip S. WARD Eigentümer, Herausgeber, Verleger / publisher © 2018 Österreichische Gesellschaft für Entomofaunistik c/o Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Burgring 7, 1010 Wien, Österreich (Austria) Myrmecological News 26 31-45 Vienna, February 2018 How common is trophobiosis with hoppers (Hemi ptera: Auchenorrhyncha) inside ant nests (Hymeno ptera: Formicidae)? Novel interactions from New Guinea and a worldwide overview Petr KLIMES, Michaela BOROVANSKA, Nichola S. PLOWMAN & Maurice LEPONCE Abstract Trophobiotic interactions between ants and honeydew-providing hemi pterans are widespread and are one of the key mechanisms that maintain ant super-abundance in ecosystems. Many of them occur inside ant nests. However, these cryptic associations are poorly understood, particularly those with hoppers (suborder Auchenorrhyncha). Here, we study tree-dwelling ant and Hemi ptera communities in nests along the Mt. Wilhelm elevational gradient in Papua New Guinea and report a new case of this symbiosis between Pseudolasius EMERY, 1887 ants and planthoppers. Fur- thermore, we provide a worldwide review of other ant-hopper interactions inside ant-built structures and compare their nature (obligate versus facultative) and distribution within the suborder Auchenorrhyncha. -

The Coexistence

Myrmecological News 20 37-42 Vienna, September 2014 Discovery of a second mushroom harvesting ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Malayan tropical rainforests Christoph VON BEEREN, Magdalena M. MAIR & Volker WITTE Abstract Ants have evolved an amazing variety of feeding habits to utilize diverse food sources. However, only one ant species, Euprenolepis procera (EMERY, 1900) (Formicidae: Formicinae), has been described as a specialist harvester of wild- growing mushrooms. Mushrooms are a very abundant food source in certain habitats, but utilizing them is expected to require specific adaptations. Here, we report the discovery of another, sympatric, and widespread mushroom harvesting ant, Euprenolepis wittei LAPOLLA, 2009. The similarity in nutritional niches of both species was expected to be accom- panied by similarities in adaptive behavior and differences due to competitive avoidance. Similarities were found in mush- room acceptance and harvesting behavior: Both species harvested a variety of wild-growing mushrooms and formed characteristic mushroom piles inside the nest that were processed continuously by adult workers. Euprenolepis procera was apparently dominant at mushroom baits displacing the smaller, less numerous E. wittei foragers. However, inter- specific competition for mushrooms is likely relaxed by differences in other niche dimensions, particularly the temporal activity pattern. The discovery of a second, widespread mushroom harvesting ant suggests that this life style is more common than previously thought, at least in Southeast Asia, and has implications for the ecology of tropical rainforests. Exploitation of the reproductive organs of fungi likely impacts spore development and distribution and thus affects the fungal community. Key words: Social insects, ephemeral food, niche differentiation, sporocarp, fungivory, Malaysia, obligate mycophagist, fungal fruit body. -

Crazy Ant (Paratrechina Sp

Midsouth Entomologist 3: 44–47 ISSN: 1936-6019 www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu Report The Invasive Rasberry Crazy Ant, Nylanderia sp. near pubens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), Reported from Mississippi MacGown. J.1* and B. Layton1 Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS, 39762 *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received: 18-XII-2009 Accepted: 23-XII-2009 Introduction The genus Nylanderia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Lasiini) currently includes 134 valid species and subspecies worldwide (LaPolla et al. 2010). Fifteen described species, including nine native and six introduced species, have been collected in the continental United States (Bolton et al. 2006, Trager 1984, Meyers 2008). Formerly, Nylanderia was considered to be a subgenus of Paratrechina and was only recently elevated to the generic level by LaPolla et al. (2010); consequently, it is referred to as Paratrechina in most of the literature. In 2002, large populations of an unknown Nylanderia species were discovered in Houston, Texas. After examination by taxonomic specialists, these ants were determined to be similar to Nylanderia pubens, the hairy crazy ant (Meyers 2008), known to occur in the Neotropical Region and in Florida (Wetterer and Keularts 2008), and similar to N. fulva (Mayr), which is native to South America (Meyers 2008). However, due to taxonomic uncertainty, this species has not been definitively identified as N. pubens, N. fulva or any of its eight subspecies, or even as an undescribed species. Therefore, at this time it is being identified as N. sp. near pubens (Meyers and Gold 2008), but it could also be referred to as N. sp. -

Fossil Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Ancient Diversity and the Rise of Modern Lineages

Myrmecological News 24 1-30 Vienna, March 2017 Fossil ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): ancient diversity and the rise of modern lineages Phillip BARDEN Abstract The ant fossil record is summarized with special reference to the earliest ants, first occurrences of modern lineages, and the utility of paleontological data in reconstructing evolutionary history. During the Cretaceous, from approximately 100 to 78 million years ago, only two species are definitively assignable to extant subfamilies – all putative crown group ants from this period are discussed. Among the earliest ants known are unexpectedly diverse and highly social stem- group lineages, however these stem ants do not persist into the Cenozoic. Following the Cretaceous-Paleogene boun- dary, all well preserved ants are assignable to crown Formicidae; the appearance of crown ants in the fossil record is summarized at the subfamilial and generic level. Generally, the taxonomic composition of Cenozoic ant fossil communi- ties mirrors Recent ecosystems with the "big four" subfamilies Dolichoderinae, Formicinae, Myrmicinae, and Ponerinae comprising most faunal abundance. As reviewed by other authors, ants increase in abundance dramatically from the Eocene through the Miocene. Proximate drivers relating to the "rise of the ants" are discussed, as the majority of this increase is due to a handful of highly dominant species. In addition, instances of congruence and conflict with molecular- based divergence estimates are noted, and distinct "ghost" lineages are interpreted. The ant fossil record is a valuable resource comparable to other groups with extensive fossil species: There are approximately as many described fossil ant species as there are fossil dinosaurs. The incorporation of paleontological data into neontological inquiries can only seek to improve the accuracy and scale of generated hypotheses. -

Ants of the Genus Formica in the Tropics by Willam Morton Wheeler

174 Psyche [August ANTS OF THE GENUS FORMICA IN THE TROPICS BY WILLAM MORTON WHEELER. The genus Formica belongs to the northern hemisphere and is best represented in the north temperate or subboreal zone, from which the number of species dimishes rapidly towards the pole and towards the equator. One species, Formica fusca, is so eurythermal that it and its many varieties may be said to be nearly coextensive in range with all the remaining species of the genus. Certain data recently accumulated show that through commerce a few of the species have succeeded in establishing themselves in the tropics. These data and the original distri- bution of the genus are briefly considered in the following paragraphs. A map of the distribution of the genus Formica shows that it covers nearly the whole of Europe as far north as North Cape, where Sparre-Schneider (1909) has taken it between latitude 69 to 70 N., that ls.within the arctic circle. In Asia the range is even wider, since it probably reaches the same high latitude and extends as far south as Soochow, China and the Himalayas (28 to 30 N.). A corresponding southward distribution in Europe is, of course, precluded by the Mediterranean. In the New World Formica covers most of the Nearctic Realm. I have shown (1913) that in Alaska F. fusca and its varieties marcida Wheeler and neorufibarbis Emery range at least as far north as 64 to 67 that is up to Fort Yukon, on the arctic circle. Eastward F, fusca occurs on the coast of Labrador, but no Formicidee are known to exist in Greenland and Iceland, according to Pjetum and Lundhein, cited by Forel (1910). -

Description of a New Genus of Primitive Ants from Canadian Amber

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 8-11-2017 Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Leonid H. Borysenko Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Borysenko, Leonid H., "Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" (2017). Insecta Mundi. 1067. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/1067 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0570 Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Leonid H. Borysenko Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes AAFC, K.W. Neatby Building 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, K1A 0C6, Canada Date of Issue: August 11, 2017 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Leonid H. Borysenko Description of a new genus of primitive ants from Canadian amber, with the study of relationships between stem- and crown-group ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Insecta Mundi 0570: 1–57 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C6CCDDD5-9D09-4E8B-B056-A8095AA1367D Published in 2017 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. -

Title Evolutionary History of a Global Invasive Ant, Paratrechina

Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina Title longicornis( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Tseng, Shu-Ping Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2020-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k22480 許諾条件により本文は2021-02-01に公開; 1. Tseng, Shu- Ping, et al. "Genetic diversity and Wolbachia infection patterns in a globally distributed invasive ant." Frontiers in genetics 10 (2019): 838. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00838 (The final publication is available at Frontier in genetics via https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2019.00838/f ull) 2. Tseng, Shu-Ping, et al. "Isolation and characterization of novel microsatellite markers for a globally distributed invasive Right ant Paratrechina longicornis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." European Journal of Entomology 116 (2019): 253-257. doi: 10.14411/eje.2019.029 (The final publication is available at European Journal of Entomology via https://www.eje.cz/artkey/eje-201901- 0029_isolation_and_characterization_of_novel_microsatellite_ markers_for_a_globally_distributed_invasive_ant_paratrec.php ) Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina longicornis Shu-Ping Tseng 2020 Contents Chapter 1 General introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Invasion history of Paratrechina longicornis is largely unknown ............... 1 1.2 Wolbachia infection in Paratrechina longicornis ......................................... 2 1.3 Unique reproduction mode in Paratrechina -

Of Sri Lanka: a Taxonomic Research Summary and Updated Checklist

ZooKeys 967: 1–142 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 CHECKLIST https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist Ratnayake Kaluarachchige Sriyani Dias1, Benoit Guénard2, Shahid Ali Akbar3, Evan P. Economo4, Warnakulasuriyage Sudesh Udayakantha1, Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo5 1 Department of Zoology and Environmental Management, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China3 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, 191132, India 4 Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Onna, Okinawa, Japan 5 Department of Zoology, Government Degree College, Shopian, Jammu and Kashmir, 190006, India Corresponding author: Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo ([email protected]) Academic editor: Marek Borowiec | Received 18 May 2020 | Accepted 16 July 2020 | Published 14 September 2020 http://zoobank.org/61FBCC3D-10F3-496E-B26E-2483F5A508CD Citation: Dias RKS, Guénard B, Akbar SA, Economo EP, Udayakantha WS, Wachkoo AA (2020) The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist. ZooKeys 967: 1–142. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 Abstract An updated checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Sri Lanka is presented. These include representatives of eleven of the 17 known extant subfamilies with 341 valid ant species in 79 genera. Lio- ponera longitarsus Mayr, 1879 is reported as a new species country record for Sri Lanka. Notes about type localities, depositories, and relevant references to each species record are given. -

Zootaxa, Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus

Zootaxa 2046: 1–25 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus Euprenolepis JOHN S. LAPOLLA Department of Biological Sciences, Towson University. 8000 York Road, Towson, Maryland 21252 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The taxonomy of Euprenolepis has been in a muddled state since it was recognized as a separate formicine ant genus. This study represents the first species-level taxonomic revision of the genus. Eight species are recognized of which six are described as new. The new species are E. echinata, E. maschwitzi, E. thrix, E. variegata, E. wittei, and E. zeta. Euprenolepis antespectans is synonymized with E. procera. Three species are excluded from the genus and transferred to Paratrechina as new combinations: P. helleri, P. steeli, and P. stigmatica. A morphologically based definition and diagnosis for the genus and an identification key to the worker caste are provided. Key words: fungivory, Lasiini, Paratrechina, Prenolepis, Pseudolasius Introduction Until recently, virtually nothing was known about the biology of Euprenolepis ants. Then, in a groundbreaking study by Witte and Maschwitz (2008), it was shown that E. procera are nomadic mushroom- harvesters, a previously unknown lifestyle among ants. In fact, fungivory is rare among animals in general (Witte and Maschwitz, 2008), making its discovery in Euprenolepis all the more spectacular. Whether or not this lifestyle is common to all Euprenolepis is unknown at this time (it is known from at least one other species [V. Witte, pers. comm.]), but a major impediment to the study of this fascinating behavior has been the inaccessibility of Euprenolepis taxonomy.