Paratrechina Longicornis (A) PEST INFORMATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

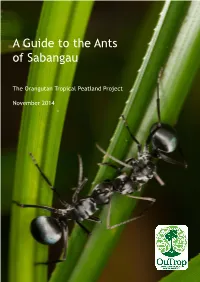

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Download PDF File (155KB)

Myrmecological News 16 35-38 Vienna, January 2012 The westernmost locations of Lasius jensi SEIFERT, 1982 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): first records in the Iberian Peninsula David CUESTA-SEGURA, Federico GARCÍA & Xavier ESPADALER Abstract Three populations of Lasius jensi SEIFERT, 1982, a temporary social parasite, from two separate regions in Spain were detected. These locations represent the westernmost populations of the species. Lasius jensi is a new record for the Iberian Peninsula, bringing the total number of native ant species to 285. Dealate queens were captured with pitfall traps from mid July to mid August. Taking into account the other species present in the three populations, the host species could be Lasius alienus (FÖRSTER, 1850), Lasius grandis FOREL, 1909 or Lasius piliferus SEIFERT, 1992. The zoogeographical significance of those populations, probably a relict from glacial refuge, is briefly discussed. Key words: Ants, Formicidae, Lasius jensi, Chthonolasius, Spain, Iberian Peninsula, new record. Myrmecol. News 16: 35-38 (online 30 June 2011) ISSN 1994-4136 (print), ISSN 1997-3500 (online) Received 21 January 2011; revision received 26 April 2011; accepted 29 April 2011 Subject Editor: Florian M. Steiner David Cuesta-Segura (contact author), Department of Biodiversity and Environmental Management, Area of Zoology, University of León, E-24071 León, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] Federico García, C/ Sant Fructuós 113, 3º 3ª, E-08004 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] Xavier Espadaler, Animal Biodiversity Group, Ecology Unit and CREAF, Autonomous University of Barcelona, E-08193 Bellaterra, Spain. Introduction Lasius jensi SEIFERT, 1982 belongs to the subgenus Chtho- tribution data. A fortiori, a distinctive situation occurs at nolasius RUZSKY, 1912, whose species are temporary so- the description of any new species. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Trevor Manendo University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2008 A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Trevor Manendo University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Manendo, Trevor, "A Phylogenetic Analysis of North American Lasius Ants Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA" (2008). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 146. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A phylogenetic analysis of North American Lasius ants based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. A Thesis Presented by Trevor Manendo to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Biology May, 2008 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science specializing in Biology. Thesis Examination Committee: ice President for Research and Dean of Graduate Studies Date: March 19,2008 ABSTRACT The ant genus Lasius (Formicinae) arose during the early Tertiary approximately 65 million years ago. Lasius is one of the most abundant and widely distributed ant genera in the Holarctic region, with 95 described species placed in six subgenera: Acanthomyops, Austrolasius, Cautolasius, Chthonolasius, Dendrolasius and Lasius. -

Crazy Ant (Paratrechina Sp

Midsouth Entomologist 3: 44–47 ISSN: 1936-6019 www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu Report The Invasive Rasberry Crazy Ant, Nylanderia sp. near pubens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), Reported from Mississippi MacGown. J.1* and B. Layton1 Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS, 39762 *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Received: 18-XII-2009 Accepted: 23-XII-2009 Introduction The genus Nylanderia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Lasiini) currently includes 134 valid species and subspecies worldwide (LaPolla et al. 2010). Fifteen described species, including nine native and six introduced species, have been collected in the continental United States (Bolton et al. 2006, Trager 1984, Meyers 2008). Formerly, Nylanderia was considered to be a subgenus of Paratrechina and was only recently elevated to the generic level by LaPolla et al. (2010); consequently, it is referred to as Paratrechina in most of the literature. In 2002, large populations of an unknown Nylanderia species were discovered in Houston, Texas. After examination by taxonomic specialists, these ants were determined to be similar to Nylanderia pubens, the hairy crazy ant (Meyers 2008), known to occur in the Neotropical Region and in Florida (Wetterer and Keularts 2008), and similar to N. fulva (Mayr), which is native to South America (Meyers 2008). However, due to taxonomic uncertainty, this species has not been definitively identified as N. pubens, N. fulva or any of its eight subspecies, or even as an undescribed species. Therefore, at this time it is being identified as N. sp. near pubens (Meyers and Gold 2008), but it could also be referred to as N. sp. -

Genus Myrmecocystus) Estimated from Mitochondrial DNA Sequences

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32 (2004) 416–421 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short communication Phylogenetics of the new world honey ants (genus Myrmecocystus) estimated from mitochondrial DNA sequences D.J.C. Kronauer,* B. Holldobler,€ and J. Gadau University of Wu€rzburg, Institute of Behavioral Physiology and Sociobiology, Biozentrum, Am Hubland, 97074 Wu€rzburg, Germany Received 8 January 2004; revised 9 March 2004 Available online 6 May 2004 1. Introduction tes. The nominate subgenus contains all the light colored, strictly nocturnal species, the subgenus Eremnocystus Honey pot workers that store immense amounts of contains small, uniformly dark colored species, and the food in the crop and are nearly immobilized due to their subgenus Endiodioctes contains species with a ferrugi- highly expanded gasters are known from a variety of ant nous head and thorax and darker gaster. Snelling (1976) species in different parts of the world, presumably as proposed that the earliest division within the genus was adaptations to regular food scarcity in arid habitats that between the line leading to the subgenus Myrmec- (Holldobler€ and Wilson, 1990). Although these so called ocystus and that leading to Eremnocystus plus Endiodi- repletes are taxonomically fairly widespread, the phe- octes (maybe based on diurnal versus nocturnal habits) nomenon is most commonly associated with species of and that the second schism occurred when the Eremno- the New World honey ant genus Myrmecocystus, whose cystus line diverged from that of Endiodioctes. repletes have a long lasting reputation as a delicacy with Based on external morphology and data from both indigenous people. -

Comprehensive Phylogeny of Myrmecocystus Honey Ants Highlights Cryptic Diversity and Infers Evolution During Aridification of the American Southwest

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 155 (2021) 107036 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Comprehensive phylogeny of Myrmecocystus honey ants highlights cryptic diversity and infers evolution during aridification of the American Southwest Tobias van Elst a,b,*, Ti H. Eriksson c,d, Jürgen Gadau a, Robert A. Johnson c, Christian Rabeling c, Jesse E. Taylor c, Marek L. Borowiec c,e,f,* a Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity, University of Münster, Hüfferstraße 1, 48149 Münster, Germany b Institute of Zoology, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Bünteweg 17, 30559 Hannover, Germany c School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, 427 E Tyler Mall, Tempe, AZ 85287-1501, USA d Beta Hatch Inc., 200 Titchenal Road, Cashmere, WA 98815, USA e Department of Entomology, Plant Pathology and Nematology, University of Idaho, 875 Perimeter Drive, Moscow, ID 83844-2329, USA f Institute for Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Studies (IBEST), University of Idaho, 875 Perimeter Drive, Moscow, ID 83844-2329, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The New World ant genus Myrmecocystus Wesmael, 1838 (Formicidae: Formicinae: Lasiini) is endemic to arid Cryptic diversity and semi-arid habitats of the western United States and Mexico. Several intriguing life history traits have been Formicidae described for the genus, the best-known of which are replete workers, that store liquified food in their largely Molecular Systematics expanded crops and are colloquially referred to as “honeypots”. Despite their interesting biology and ecological Myrmecocystus importance for arid ecosystems, the evolutionary history of Myrmecocystus ants is largely unknown and the Phylogenomics Ultraconserved elements current taxonomy presents an unsatisfactory systematic framework. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FORAGING STRATEGIES AND AGGRESSION PATTERNS OF NYLANDERIA FULVA (Mayr) (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE) IN NORTH CENTRAL FLORIDA By STEPHANIE KAY HILL A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Stephanie Kay Hill 2 To my family and friends that shared in this journey with me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express my deepest appreciation to all the folks who helped and guided me through my graduate studies. My many thanks and gratitude to my major professor, Dr. Phil Koehler, for all of his encouragement, dedication, patience, and guidance. I would especially like the thank Dr. Roberto Pereira for his time and patience as we went through statistical processes and editing. I gratefully thank Dr. Grady Roberts for mentoring me through my agricultural education minor. Thanks to Dr. David Williams for all of his support and keeping me on the ball. Dr. Rebecca Baldwin, thank you for being my mentor and allowing me to have so many teaching experiences. A huge thank you and my upmost respect to Mark Mitola. I was lucky to have you assist me. We have many memories that I hope we can reminisce over years down the road. Thank you to the ever wonderful Liz Pereira and Tiny Willis. Without the two of you, the Urban Lab would fall apart. Thank you to my closest and dearest lab mates: Jodi Scott, Bennett Jordan, Joe DiClaro, Anda Chaskopoulou, Margie Lehnert, and Ricky Vazquez In particular, Jodi provided me with support and comic relief. -

Formicidae: Catalogue of Family-Group Taxa

FORMICIDAE: CATALOGUE OF FAMILY-GROUP TAXA [Note (i): the standard suffixes of names in the family-group, -oidea for superfamily, –idae for family, -inae for subfamily, –ini for tribe, and –ina for subtribe, did not become standard until about 1905, or even much later in some instances. Forms of names used by authors before standardisation was adopted are given in square brackets […] following the appropriate reference.] [Note (ii): Brown, 1952g:10 (footnote), Brown, 1957i: 193, and Brown, 1976a: 71 (footnote), suggested the suffix –iti for names of subtribal rank. These were used only very rarely (e.g. in Brandão, 1991), and never gained general acceptance. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ed. 4, 1999), now specifies the suffix –ina for subtribal names.] [Note (iii): initial entries for each of the family-group names are rendered with the most familiar standard suffix, not necessarily the original spelling; hence Acanthostichini, Cerapachyini, Cryptocerini, Leptogenyini, Odontomachini, etc., rather than Acanthostichii, Cerapachysii, Cryptoceridae, Leptogenysii, Odontomachidae, etc. The original spelling appears in bold on the next line, where the original description is cited.] ACANTHOMYOPSINI [junior synonym of Lasiini] Acanthomyopsini Donisthorpe, 1943f: 618. Type-genus: Acanthomyops Mayr, 1862: 699. Taxonomic history Acanthomyopsini as tribe of Formicinae: Donisthorpe, 1943f: 618; Donisthorpe, 1947c: 593; Donisthorpe, 1947d: 192; Donisthorpe, 1948d: 604; Donisthorpe, 1949c: 756; Donisthorpe, 1950e: 1063. Acanthomyopsini as junior synonym of Lasiini: Bolton, 1994: 50; Bolton, 1995b: 8; Bolton, 2003: 21, 94; Ward, Blaimer & Fisher, 2016: 347. ACANTHOSTICHINI [junior synonym of Dorylinae] Acanthostichii Emery, 1901a: 34. Type-genus: Acanthostichus Mayr, 1887: 549. Taxonomic history Acanthostichini as tribe of Dorylinae: Emery, 1901a: 34 [Dorylinae, group Cerapachinae, tribe Acanthostichii]; Emery, 1904a: 116 [Acanthostichii]; Smith, D.R. -

Title Evolutionary History of a Global Invasive Ant, Paratrechina

Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina Title longicornis( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Tseng, Shu-Ping Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2020-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k22480 許諾条件により本文は2021-02-01に公開; 1. Tseng, Shu- Ping, et al. "Genetic diversity and Wolbachia infection patterns in a globally distributed invasive ant." Frontiers in genetics 10 (2019): 838. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00838 (The final publication is available at Frontier in genetics via https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2019.00838/f ull) 2. Tseng, Shu-Ping, et al. "Isolation and characterization of novel microsatellite markers for a globally distributed invasive Right ant Paratrechina longicornis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." European Journal of Entomology 116 (2019): 253-257. doi: 10.14411/eje.2019.029 (The final publication is available at European Journal of Entomology via https://www.eje.cz/artkey/eje-201901- 0029_isolation_and_characterization_of_novel_microsatellite_ markers_for_a_globally_distributed_invasive_ant_paratrec.php ) Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Evolutionary history of a global invasive ant, Paratrechina longicornis Shu-Ping Tseng 2020 Contents Chapter 1 General introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Invasion history of Paratrechina longicornis is largely unknown ............... 1 1.2 Wolbachia infection in Paratrechina longicornis ......................................... 2 1.3 Unique reproduction mode in Paratrechina -

A Review of Myrmecophily in Ant Nest Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Paussinae): Linking Early Observations with Recent Findings

Naturwissenschaften (2007) 94:871–894 DOI 10.1007/s00114-007-0271-x REVIEW A review of myrmecophily in ant nest beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae: Paussinae): linking early observations with recent findings Stefanie F. Geiselhardt & Klaus Peschke & Peter Nagel Received: 15 November 2005 /Revised: 28 February 2007 /Accepted: 9 May 2007 / Published online: 12 June 2007 # Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Myrmecophily provides various examples of as “bombardier beetles” is not used in contact with host how social structures can be overcome to exploit vast and ants. We attempt to trace the evolution of myrmecophily in well-protected resources. Ant nest beetles (Paussinae) are paussines by reviewing important aspects of the association particularly well suited for ecological and evolutionary between paussine beetles and ants, i.e. morphological and considerations in the context of association with ants potential chemical adaptations, life cycle, host specificity, because life habits within the subfamily range from free- alimentation, parasitism and sound production. living and predatory in basal taxa to obligatory myrme- cophily in derived Paussini. Adult Paussini are accepted in Keywords Evolution of myrmecophily. Paussinae . the ant society, although parasitising the colony by preying Mimicry. Ant parasites . Defensive secretion . on ant brood. Host species mainly belong to the ant families Host specificity Myrmicinae and Formicinae, but at least several paussine genera are not host-specific. Morphological adaptations, such as special glands and associated tufts of hair Introduction (trichomes), characterise Paussini as typical myrmecophiles and lead to two different strategical types of body shape: A great diversity of arthropods live together with ants and while certain Paussini rely on the protective type with less profit from ant societies being well-protected habitats with exposed extremities, other genera access ant colonies using stable microclimate (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990; Wasmann glandular secretions and trichomes (symphile type). -

Zootaxa, Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus

Zootaxa 2046: 1–25 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Taxonomic Revision of the Southeast Asian Ant Genus Euprenolepis JOHN S. LAPOLLA Department of Biological Sciences, Towson University. 8000 York Road, Towson, Maryland 21252 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The taxonomy of Euprenolepis has been in a muddled state since it was recognized as a separate formicine ant genus. This study represents the first species-level taxonomic revision of the genus. Eight species are recognized of which six are described as new. The new species are E. echinata, E. maschwitzi, E. thrix, E. variegata, E. wittei, and E. zeta. Euprenolepis antespectans is synonymized with E. procera. Three species are excluded from the genus and transferred to Paratrechina as new combinations: P. helleri, P. steeli, and P. stigmatica. A morphologically based definition and diagnosis for the genus and an identification key to the worker caste are provided. Key words: fungivory, Lasiini, Paratrechina, Prenolepis, Pseudolasius Introduction Until recently, virtually nothing was known about the biology of Euprenolepis ants. Then, in a groundbreaking study by Witte and Maschwitz (2008), it was shown that E. procera are nomadic mushroom- harvesters, a previously unknown lifestyle among ants. In fact, fungivory is rare among animals in general (Witte and Maschwitz, 2008), making its discovery in Euprenolepis all the more spectacular. Whether or not this lifestyle is common to all Euprenolepis is unknown at this time (it is known from at least one other species [V. Witte, pers. comm.]), but a major impediment to the study of this fascinating behavior has been the inaccessibility of Euprenolepis taxonomy. -

Identification, Distribution and Control of an Invasive

IDENTIFICATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONTROL OF AN INVASIVE PEST ANT, Paratrechina SP. (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE), IN TEXAS A Dissertation by JASON MICHAEL MEYERS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2008 Major Subject: Entomology IDENTIFICATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONTROL OF AN INVASIVE PEST ANT, Paratrechina SP. (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE), IN TEXAS A Dissertation by JASON MICHAEL MEYERS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Committee Chair, Roger Gold Committee Members, Jerry Cook Albert Mulenga Leon Russell Jr. Jim Woolley Head of Department, Kevin Heinz August 2008 Major Subject: Entomology iii ABSTRACT Identification, Distribution and Control of an Invasive Pest Ant, Paratrechina sp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in Texas. (August 2008) Jason Michael Meyers, B.S., Southwest Missouri State University; M.S., University of Arkansas Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Roger Gold Invasive species are capable of causing considerable damage to natural ecosystems, agricultures and economies throughout the world. These invasive species must be identified and adequate control measures should be investigated to prevent and reduce the negative effects associated with exotic species. A recent introduction of an exotic ant, Paratrechina sp. nr. pubens, has caused tremendous economic and ecological damage to southern Texas. Morphometric and phylogenetic procedures were used to identify this pest ant, P. sp. nr. pubens, to Southern Texas. The populations in Texas were found to be slightly different but not discriminating from P. pubens populations described in previous literature.