Large Print Exhibition Text America's Presidents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

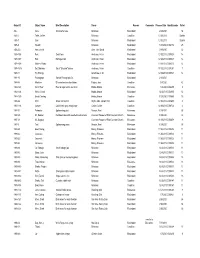

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy Commencement Address

Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy Commencement Address May 19, 2013 Bob Lang Thank you for inviting me to be a part of the celebration of your commencement -- graduation from the University of Wisconsin's Robert M. La Follette School of Public Policy. I have had the privilege of serving in Wisconsin's Legislative Fiscal Bureau with many La Follette graduates, including the 10 who are currently colleagues of mine at the Bureau. I am honored to be with you today. ____________________________ I have two favorite commencement speeches. The first, written 410 years ago, was not delivered to a graduating class, but rather, to an individual. It was, however, a commencement address in the true meaning of the word -- that is to recognize a beginning -- a transition from the present to the future. And, in the traditional sense of commencement speeches, was filled with advice. The speech was given by a father to his son, in Shakespeare's Hamlet. Polonius, chief councilor to Denmark's King Claudius, gives his son Laertes sage advice as the young man patiently waits for his talkative father to complete his lengthy speech and bid him farewell before the son sets sail for France to Page 1 continue his studies. "Those friends thou hast, grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel." "Give every man thine ear, but few thy voice." "Neither a borrower nor a lender be." "This above all, to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man." The second of my favorite commencement addresses was delivered to a graduating college class by Thornton Mellen. -

Download File

The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Anne Claire Diebel All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Outward Turn: Personality, Blankness, and Allure in American Modernism Anne Claire Diebel The history of personality in American literature has surprisingly little to do with the differentiating individuality we now tend to associate with the term. Scholars of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American culture have defined personality either as the morally vacuous successor to the Protestant ideal of character or as the equivalent of mass-media celebrity. In both accounts, personality is deliberately constructed and displayed. However, hiding in American writings of the long modernist period (1880s–1940s) is a conception of personality as the innate capacity, possessed by few, to attract attention and elicit projection. Skeptical of the great American myth of self-making, such writers as Henry James, Theodore Dreiser, Gertrude Stein, Nathanael West, and Langston Hughes invented ways of representing individuals not by stable inner qualities but by their fascinating—and, often, gendered and racialized—blankness. For these writers, this sense of personality was not only an important theme and formal principle of their fiction and non-fiction writing; it was also a professional concern made especially salient by the rise of authorial celebrity. This dissertation both offers an alternative history of personality in American literature and culture and challenges the common critical assumption that modernist writers took the interior life to be their primary site of exploration and representation. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

Nixon Pardon Hungate Subcommittee – Ford Testimony, 1974/10/17 (3)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 34, folder “Nixon Pardon Hungate Subcommittee – Ford Testimony, 1974/10/17 (3)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Exact duplicates within this folder were not digitized. Digitized from Box 34 of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library \( ~,- STATEt·1EIH OF PRESIDENT GERALD FORD HOUSE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY Subcommittee on Criminal Justice October 17, 1974 We meet here today to review the facts and circumstances that were the basis for my pardon of .former President Nixon on September 8, 1974. · I \'/ant very much to have those facts and circumstances known. The American people want to know them. And members of the Congress want to know them. The two Congressional resolutions of inquiry now before this Committee serve those purposes. That is why I have volunteered to appear before you this morning, and I welcome and thank you for this opportunity to speak to the questions raised by the resolutions. -

James Knox Polk Collection, 1815-1949

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 POLK, JAMES KNOX (1795-1849) COLLECTION 1815-1949 Processed by: Harriet Chapell Owsley Archival Technical Services Accession Numbers: 12, 146, 527, 664, 966, 1112, 1113, 1140 Date Completed: April 21, 1964 Location: I-B-1, 6, 7 Microfilm Accession Number: 754 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection of James Knox Polk (1795-1849) papers, member of Tennessee Senate, 1821-1823; member of Tennessee House of Representatives, 1823-1825; member of Congress, 1825-1839; Governor of Tennessee, 1839-1841; President of United States, 1844-1849, were obtained for the Manuscripts Section by Mr. and Mrs. John Trotwood Moore. Two items were given by Mr. Gilbert Govan, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and nine letters were transferred from the Governor’s Papers. The materials in this collection measure .42 cubic feet and consist of approximately 125 items. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the James Knox Polk Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT The James Knox Polk Collection, composed of approximately 125 items and two volumes for the years 1832-1848, consist of correspondence, newspaper clippings, sketches, letter book indexes and a few miscellaneous items. Correspondence includes letters by James K. Polk to Dr. Isaac Thomas, March 14, 1832, to General William Moore, September 24, 1841, and typescripts of ten letters to Major John P. Heiss, 1844; letters by Sarah Polk, 1832 and 1891; Joanna Rucker, 1845- 1847; H. Biles to James K. Polk, 1833; William H. -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

Time Line of the Progressive Era from the Idea of America™

Time Line of The Progressive Era From The Idea of America™ Date Event Description March 3, Pennsylvania Mine Following an 1869 fire in an Avondale mine that kills 110 1870 Safety Act of 1870 workers, Pennsylvania passes the country's first coal mine safety passed law, mandating that mines have an emergency exit and ventilation. November Woman’s Christian Barred from traditional politics, groups such as the Woman’s 1874 Temperance Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) allow women a public Union founded platform to participate in issues of the day. Under the leadership of Frances Willard, the WCTU supports a national Prohibition political party and, by 1890, counts 150,000 members. February 4, Interstate The Interstate Commerce Act creates the Interstate Commerce 1887 Commerce act Commission to address price-fixing in the railroad industry. The passed Act is amended over the years to monitor new forms of interstate transportation, such as buses and trucks. September Hull House opens Jane Addams establishes Hull House in Chicago as a 1889 in Chicago “settlement house” for the needy. Addams and her colleagues, such as Florence Kelley, dedicate themselves to safe housing in the inner city, and call on lawmakers to bring about reforms: ending child labor, instituting better factory working conditions, and compulsory education. In 1931, Addams is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. November “White Caps” Led by Juan Jose Herrerra, the “White Caps” (Las Gorras 1889 released from Blancas) protest big business’s monopolization of land and prison resources in the New Mexico territory by destroying cattlemen’s fences. The group’s leaders gain popular support upon their release from prison in 1889. -

APUSH 3 Marking Period Plan of Study WEEK 1: PROGRESSIVISM

APUSH 3rd Marking Period Plan of Study Weekly Assignments: One pagers covering assigned reading from the text, reading quiz or essay covering week‘s topics WEEK 1: PROGRESSIVISM TIME LINE OF EVENTS: 1890 National Women Suffrage Association 1901 McKinley Assassinated T.R. becomes President Robert LaFollette, Gov. Wisconsin Tom Johnson, Mayor of Cleveland Tenement House Bill passed NY 1902 Newlands Act Anthracite Coal Strike 1903 Women‘s Trade Union founded Elkin‘s Act passed 1904 Northern Securities vs. U.S. Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty Roosevelt Corollary Lincoln Steffens, Shame of Cities 1905 Lochner vs. New York 1906 Upton Sinclair, The Jungle Hepburn Act Meat Inspection Act Pure Food and Drugs Act 1908 Muller vs. Oregon 1909 Croly publishes, The Promises of American Life NAACP founded 1910 Ballinger-Pinchot controversy Mann-Elkins Act 1912 Progressive Party founded by T. R. Woodrow Wilson elected president Department of Labor established 1913 Sixteenth Amendment ratified Seventeenth Amendment ratified Underwood Tariff 1914 Clayton Act legislated Federal Reserve Act Federal Trade Commission established LECTURE OBJECTIVES: This discussion will cover the main features of progressivism and the domestic policies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. It seeks to trace the triumph of democratic principles established in earlier history. A systematic attempt to evaluate progressive era will be made. I. Elements of Progressivism and Reform A. Paradoxes in progressivism 1. A more respectable ―populism‖ 2. Elements of conservatism B. Antecedents to progressivism 1. Populism 2. The Mugwumps 3. Socialism C. The Muckrakers 1. Ida Tarbell 2. Lincoln Stephens - Shame of the Cities 3. David Phillips - Treasure of the Senate 4.