Open 1-Mingyuan Chen Master-Thesis Final Submission.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. Huangjindui

产品总称 委托方名称(英) 申请地址(英) Huangjindui Industrial Park, Shanggao County, Yichun City, Jiangxi Province, Cereal Series/Protein Series Jiangxi Cowin Food Co., Ltd. China Folic acid/D-calcium Pantothenate/Thiamine Mononitrate/Thiamine East of Huangdian Village (West of Tongxingfengan), Kenli Town, Kenli County, Hydrochloride/Riboflavin/Beta Alanine/Pyridoxine Xinfa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Dongying City, Shandong Province, 257500, China Hydrochloride/Sucralose/Dexpanthenol LMZ Herbal Toothpaste Liuzhou LMZ Co.,Ltd. No.282 Donghuan Road,Liuzhou City,Guangxi,China Flavor/Seasoning Hubei Handyware Food Biotech Co.,Ltd. 6 Dongdi Road, Xiantao City, Hubei Province, China SODIUM CARBOXYMETHYL CELLULOSE(CMC) ANQIU EAGLE CELLULOSE CO., LTD Xinbingmaying Village, Linghe Town, Anqiu City, Weifang City, Shandong Province No. 569, Yingerle Road, Economic Development Zone, Qingyun County, Dezhou, biscuit Shandong Yingerle Hwa Tai Food Industry Co., Ltd Shandong, China (Mainland) Maltose, Malt Extract, Dry Malt Extract, Barley Extract Guangzhou Heliyuan Foodstuff Co.,LTD Mache Village, Shitan Town, Zengcheng, Guangzhou,Guangdong,China No.3, Xinxing Road, Wuqing Development Area, Tianjin Hi-tech Industrial Park, Non-Dairy Whip Topping\PREMIX Rich Bakery Products(Tianjin)Co.,Ltd. Tianjin, China. Edible oils and fats / Filling of foods/Milk Beverages TIANJIN YOSHIYOSHI FOOD CO., LTD. No. 52 Bohai Road, TEDA, Tianjin, China Solid beverage/Milk tea mate(Non dairy creamer)/Flavored 2nd phase of Diqiuhuanpo, Economic Development Zone, Deqing County, Huzhou Zhejiang Qiyiniao Biological Technology Co., Ltd. concentrated beverage/ Fruit jam/Bubble jam City, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China Solid beverage/Flavored concentrated beverage/Concentrated juice/ Hangzhou Jiahe Food Co.,Ltd No.5 Yaojia Road Gouzhuang Liangzhu Street Yuhang District Hangzhou Fruit Jam Production of Hydrolyzed Vegetable Protein Powder/Caramel Color/Red Fermented Rice Powder/Monascus Red Color/Monascus Yellow Shandong Zhonghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd. -

Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage the Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China

review of Religion and chinese society 3 (2016) 189-222 Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage The Network of Pilgrimage Routes in Nineteenth-Century China Marcus Bingenheimer Temple University [email protected] Abstract In the early nineteenth century the monk Ruhai Xiancheng 如海顯承 traveled through China and wrote a route book recording China’s most famous pilgrimage routes. Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage (Canxue zhijin 參學知津) describes, station by station, fifty-six pilgrimage routes, many converging on famous mountains and urban centers. It is the only known route book that was authored by a monk and, besides the descriptions of the routes themselves, Knowing the Paths contains information about why and how Buddhists went on pilgrimage in late imperial China. Knowing the Paths was published without maps, but by geo-referencing the main stations for each route we are now able to map an extensive network of monastic pilgrimage routes in the nineteenth century. Though most of the places mentioned are Buddhist sites, Knowing the Paths also guides travelers to the five marchmounts, popular Daoist sites such as Mount Wudang, Confucian places of worship such as Qufu, and other famous places. The routes in Knowing the Paths traverse not only the whole of the country’s geogra- phy, but also the whole spectrum of sacred places in China. Keywords Knowing the Paths of Pilgrimage – pilgrimage route book – Qing Buddhism – Ruhai Xiancheng – “Ten Essentials of Pilgrimage” 初探«參學知津»的19世紀行腳僧人路線網絡 摘要 十九世紀早期,如海顯承和尚在遊歷中國後寫了一本關於中國一些最著名 的朝聖之路的路線紀錄。這本「參學知津」(朝聖之路指引)一站一站地 -

INTG20140310 Minutes (371)), a Second Document Is Attached to This Message: the List of the 108 Auspicious Signs Found in Buddha's Footprints

Informal Northern Thai Group Bulletin March 09, 2014 ATTENTION! TWO TALKS IN MARCH: 11 AND 25 MARCH 1. MINUTES OF THE 371TH INTG MEETING. FEBRUARY 18, 2014: “FOLLOWING BUDDHA’S FOOTPRINTS (BUDDHAPĀDA)”. A TALK BY JACQUES DE GUERNY. 2. NEXT MEETING: TUESDAY, MARCH 11, 2014, 7:30 PM: “THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF STAND-ALONE MOVIE THEATERS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: A VISUAL NARRATIVE”. A TALK BY PHILIP JABLON. 3. 2ND MARCH MEETING: TUESDAY, MARCH 25, 2014, 7:30 PM: “ETHNIC DIVERSITY OF LAOS: A MUSEUM PERSPECTIVE”. A TALK BY TARA GUJADHUR 3. FUTURE INTG MEETINGS. 4. INTG CONTACTS: CONVENOR, SECRETARY, WEBSITE. 1. MINUTES OF THE 371TH INTG MEETING, FEBRUARY 18, 2014 “FOLLOWING BUDDHA’S FOOTPRINTS (BUDDHAPĀDA)” A TALK BY JACQUES DE GUERNY 1.1. PRESENT : Hans Bänziger, Saengdao Bänziger, Dianne Barber-Riley, Mark Barber-Riley, Frederic Bourdier, Kay M. Calavan, Michael M. Calavan, Roger Casas, Peter Daxy, Hilary Disch, Ron Emmons, Louis Gabaude, Anne Marie Garretta, Michel Garretta, Pierre-Antoine Garetta, Trevor Gibson, Ivan Hall, Sjon Hauser, Frédéric Hurteau, Anthony Irwin, Jiraporn Klasson, Brenda Joyce, Mahajirasak Jiraddhammo, George Olson, Mony Pen, Poonsouk na Chiengmai, Surya Smutkupt, Edward van Tryll, Meyer Walter, Rebecca Weldon, Spencer Wood, Layle Wood, a total of 32 at least. 1.2. The 371th Talk : “FOLLOWING BUDDHA'S FOOTPRINTS (BUDDHAPĀDA). A TALK BY JACQUES DE GUERNY. You are invited to read this sketch of Jacques de Guerny's talk with an eye on the PowerPoint presentation by the speaker: Buddhapada-deGuerny.pptx. However, due to its "weight", I cannot send this PowerPoint presentation as an attachment. -

Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde Chuadeng

The Hokun Trust is pleased to support the fifth volume of a complete translation of this classic of Chan (Zen) Buddhism by Randolph S. Whitfield. The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp is a religious classic of the first importance for the practice and study of Zen which it is hoped will appeal both to students of Buddhism and to a wider public interested in religion as a whole. Contents Foreword by Albert Welter Preface Acknowledgements Introduction Appendix to the Introduction Abbreviations Book Eighteen Book Nineteen Book Twenty Book Twenty-one Finding List Bibliography Index Foreword The translation of the Jingde chuandeng lu (Jingde era Record of the Transmission of the Lamp) is a major accomplishment. Many have reveled in the wonders of this text. It has inspired countless numbers of East Asians, especially in China, Japan and Korea, where Chan inspired traditions – Chan, Zen, and Son – have taken root and flourished for many centuries. Indeed, the influence has been so profound and pervasive it is hard to imagine Japanese and Korean cultures without it. In the twentieth century, Western audiences also became enthralled with stories of illustrious Zen masters, many of which are rooted in the Jingde chuandeng lu. I remember meeting Alan Ginsburg, intrepid Beat poet and inveterate Buddhist aspirant, in Shanghai in 1985. He had been invited as part of a literary cultural exchange between China and the U. S., to perform a series of lectures for students at Fudan University, where I was a visiting student. Eager to meet people who he could discuss Chinese Buddhism with, I found myself ushered into his company to converse on the subject. -

Gongan Collections I 公案集公案集 Gongangongan Collectionscollections I I Juhn Y

7-1 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 7-1 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I COLLECTIONS GONGAN 公案集公案集 GONGANGONGAN COLLECTIONSCOLLECTIONS I I JUHN Y. AHN JUHN Y. (EDITOR) JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 7-1 公案集 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 7-1 Gongan Collections I Edited by John Jorgensen Translated by Juhn Y. Ahn Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-10-2 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 7-1 公案集 GONGAN COLLECTIONS I EDITED BY JOHN JORGENSEN TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY JUHN Y. AHN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. -

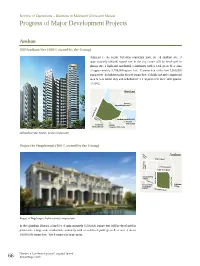

Progress of Major Development Projects

Review of Operations – Business in Mainland China and Macau Progress of Major Development Projects Anshan Old Stadium Site (100% owned by the Group) Adjacent to the scenic Yufoshan municipal park, an old stadium site of approximately 600,000 square feet in the city centre will be developed in phases into a high-end residential community with a total gross floor area of approximately 3,700,000 square feet. Construction of the first 1,200,000 square feet of residences plus 60,000 square feet of clubhouse and commercial area is now under way and scheduled for completion in the fourth quarter of 2013. Anshan Anshan International Hotel YuanlinHuaixiang Road Road Anshan Gateball Field Anshan Yufo Court Anshanshi Anshan Justice Bureau Laoganbu University Old Stadium Site, Anshan (artist’s impression) Project in Yingchengzi (100% owned by the Group) Hunan Street Anshan Yingcui Road Huihuayuan Road Yingcheng Cuijia North Road Gaoguanling Village Anxia Line Cuijia West Road West Cuijia Gaoguanling Cuijiatun Elementary Road Guihua Village School Kuanggong Road Project in Yingchengzi, Anshan (artist’s impression) In the Qianshan District, a land lot of approximately 5,500,000 square feet will be developed in phases into a large scale residential community with a total developable gross floor area of about 14,000,000 square feet. Site formation is in progress. Henderson Land Development Company Limited 66 Annual Report 2011 Review of Operations – Business in Mainland China and Macau • Progress of Major Development Projects Changsha The Arch of Triumph -

Documentation and Information Centers

• . I Advances in Biopharmaceutical Technology in China September 2006 Editor: Eric S. Langer BioPlan Associates, Inc. Rockville, MD SOCIETY FOR INDUSTRIAL MICROBIOLOGY Arlington, VA BioPlan Associates, Inc. 15200 Shady Grove Road, Suite 202 Rockville MD 20850 USA 301-921-9074 www.bioplanassociates.com and Society for Industrial Microbiology 3929 Old Lee Highway Suite 92A Fairfax, VA 22030-2421 703-691-3357 Copyright © 2006 by Eric S. Langer All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. For information on special discounts or permissions contact BioPlan Associates, Inc. at 301- 921-9074, or [email protected] Editor: Eric S. Langer Project Directors: Yibing Eliza Zhou Gloria Jacobovitz Production: ES Illustation and Design, Inc. Text and Cover Design: Esperance Shatarah ISBN 1-934106-00-3 ii Acknowledgment This project would not have been possible without the exceptional efforts of the many people involved. In particular, we would like to thank: Yibing Eliza Zhou, Project Director Gloria Jacobovitz, Project Director, US ES Illustration and Design, Inc., Design/Production Manager, Cover Graphics. Colleen Foti, Production Benjamin J. Kemp, Data Management and Acquisition We would also especially like to thank our reviewers, whose expertise ensured this volume -

Environmental Impact Assessment Report Form

E1717 v1 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment Report Public Disclosure Authorized Project Description: Biogas Engineering Project for Excrement & Sewage Treatment and Resource Utilization Public Disclosure Authorized Implementation Agency (Official Seal): Shandong Minhe Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. Public Disclosure Authorized EIA Agency: Shandong Academy of Environmental Science Legal Representative: Bian Xingyu Project Description: Biogas Engineering Project for Excrement & Sewage Treatment and Resource Utilization of Shandong Minhe Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. Type of Document: Environmental Impact Assessment Report Form Add.: 50 Lishan Rd. Jinan Tel.: 0531-85870051 0531-85870004 Fax : 0531-85870050 0531-85870015 Postal Code: 250013 - 1 Shandong Minhe Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. Biogas Engineering Project for Excrement & Sewage Treatment and Resource Utilization Environmental Impact Assessment Report Form Director in Charge (Signature): Department Chief (Signature): Responsibilities and Duties of Assessment & Review Personnel Technical EIA Certificate Duty Signature Specialty Task Title No. Project management Senior Environmental Certificate No. Preparation & Engineer Engineering -A24020014 assessment Internal Senior Environmental Certificate No. Review review Engineer Engineering -A24020033 Academic Environmental Certificate No. committee Engineer Review Engineering -A24020032 review Audit & Research Environmental Certificate No. Review issuance Fellow Engineering -A24020031 - 2 Project Profile Project Biogas Engineering -

Records of the Transmission of the Lamp: Volume 2

The Hokun Trust is pleased to support the second volume of a complete translation of this classic of Chan (Zen) Buddhism by Randolph S. Whitfield. The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp is a religious classic of the first importance for the practice and study of Zen which it is hoped will appeal both to students of Buddhism and to a wider public interested in religion as a whole. Contents Preface Acknowledgements Introduction Abbreviations Book Four Book Five Book Six Book Seven Book Eight Book Nine Finding List Bibliography Index Reden ist übersetzen – aus einer Engelsprache in eine Menschensprache, das heist, Gedanken in Worte, – Sachen in Namen, – Bilder in Zeichen. Johann Georg Hamann, Aesthetica in nuce. Eine Rhapsodie in kabbalistischer Prosa. 1762. Preface The doyen of Buddhism in England, Christmas Humphreys (1901- 1983), once wrote in his book, Zen Buddhism, published in 1947, that ‘The “transmission” of Zen is a matter of prime difficulty…Zen… is ex hypothesi beyond the intellect…’1 Ten years later the Japanese Zen priest Sohaku Ogata (1901-1973) from Chotoko-in, in the Shokufuji Temple compound in Kyoto came to visit the London Buddhist Society that Humphreys had founded in the 1920s. The two men had met in Kyoto just after the Second World War. Sohaku Ogata’s ambition was to translate the whole of the Song dynasty Chan (Zen) text Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (hereafter CDL), which has never been fully translated into any language (except modern Chinese), into English. Before his death Sohaku Ogata managed to translate the first ten books of this mammoth work.2 The importance of this compendium had not gone unnoticed. -

Wfrs Triennial Report 2012

WFRS TRIENNIAL REPORT 2012 WFRS TRIENNIAL REPORT 2012 WFRS TRIENNIAL REPORT 2012 Published for the World Federation of Rose Societies By the Federation of Rose Societies of South Africa EDITOR Sheenagh Harris Assisted by Di Girdwood WORLD FEDERATION OF ROSE SOCIETIES Founded 1968 www.worldrose.org The World Federation of Rose Societies is registered in Great Britain as a company limited by guarantee and as a charity under the number 1063582. The objectives of the Society, as stated in the constitution, are: To encourage and facilitate the interchange of information about and knowledge of the rose between national rose societies. To coordinate the holding of international conventions and exhibitions. To encourage, and where appropriate, sponsor research into problems concerning the rose. To establish common standards for judging new rose seedlings. To assist in coordinating the registration of new rose names. To establish a uniform system of rose classification. To grant international honours and/or awards. To encourage and advance international cooperation in all other matters concerning the rose. Gérald Meylan - Immediate Past President, Sheenagh Harris - President, Helga Brichet - Past President, Ken Grapes - Past President in attendance at the 60th Anniversary of the Baden Baden Rose Trials - 2012 1 CONTENTS 2 Foreword – Ken Grapes 3 Preface – Helga Brichet 4 President’s Report 7 Official Visits of the President 10 Immediate Past President’s Message 15 WFRS Vice Presidents Reports 34 WFRS Officers 36 WFRS Standing Committees -

China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project

China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project Strengthening Leadership Capacity for Effective Management of China’s Protected Areas YEAR II A partnership of the China State Forestry Administration The Nature Conservancy China Program East-West Center 4-31 May 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………….…..…1 Map of China Model National Nature Reserves ………………………………………………………...…5 Descriptions of China’s 51 Model National Nature Reserves…………………………………..….………6 Training Needs for Protected Area Managers……………………………………………………….…….19 Year II Participants……………….……………………………………………………………….……….21 Participant Contact Information………………………………………………..…………….…….……...29 Classroom Training Schedule, Beijing Forestry University ….……………………………………...……31 Overview of Field Study and Collaborative Learning Component………......……………….…….…..…33 U.S. Field Study Agenda………………………………………………………………………...….……..36 U.S. Field Study Organizations…………………………………………………………….………..…….52 U.S. Field Study Speakers…………………………...……………………………………………….……60 U.S. Field Study Speaker Contact Information……………………………………………………………74 Project Staff ……………………………………….……………………………………………………....80 Project Staff Contact Information………………………………………………………………………....83 China Protected Areas Leadership Alliance Project Strengthening Leadership Capacity for Effective Management of China’s Protected Areas Executive Summary Protection of the natural and cultural heritage of China depends on the effective management of the nation’s protected areas. The Government of China has set aside fifteen -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 264 5th International Conference on Education, Management, Arts, Economics and Social Science (ICEMAESS 2018) Research on Protection and Development of Xi’an Historical and Cultural Blocks Shule Wei Department of Architecture, School of Architecture and Art Design, Xi’an Peihua University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China, 710125 Keywords: historical and cultural blocks; protection and development; Sanxue Street; tourism Abstract: The historical value and important status of historical blocks makes it irreplaceable in cities. In terms of historical and cultural blocks depending on tourism industry, this paper puts forward multi-layered protection strategy of point (individual building), line (traditional lanes) and plane (activity space), and dynamic mode of “small scale, gradualism and microcirculation” to adapt to the requirement of changes, further explore characteristics of historical and cultural blocks, inspire its vitality, and better inherit history and culture of Xi’an. 1. Introduction 1.1 Research Background At present, a large number of historical buildings in China are on the verge of destruction. The pattern of traditional lanes is contradicted with the need of modern people. The flourishing tourism industry causes overexploitation. Without unique characteristics in cities and clear local industrial features, the situation of “stereotyped scenes” in different areas is severer. How to protect and continuously develop historical blocks to adapt to the requirement of the new era becomes an important project. 1.2 Research Objectives This paper, with reference to domestic and foreign protection and development modes of historical blocks, aims to discuss how to develop historical and cultural blocks from the perspective of tourism, put forward comprehensive basic theory frame with reference value, taking Sanxue Street blocks in Xi’an as a specific case, and provide solutions with a certain regularity.