Phd Dissertation, Stanford University, 1967), 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUMBA-MENU-WEBSITE-AUGUST.Pdf

Open Hours 12PM TO 1AM Club Vista Mare, Unit 6, Palm Jumeirah 12PM TO 3AM(THURSDAY- FRIDAY) SALUDSALUD MIMI FAMILIAFAMILIA About BITES LALA TRADICIONTRADICION Empanadas de Ropa Vieja 4pcs (G)(D) 60 RUMBARUMBA Homemade pastry, shredded beef, bone marrow aioli CUBANACUBANA Tostones y Enchilados 4pcs (S)(D) 55 Crispy green plantain, shrimps, diabla sauce Daiquiri 45 White rum, fresh lemon juice, fresh CUBANCUBAN Croquetas 5pcs (D)(G) 65 sugarcane juice, maraschino Veal brisket, turkey ham, cheese, jalapeño aioli Mojito 48 BARBAR && Camarones Rellenos 5pcs (G)(S)(D) 70 White rum, fresh lemon juice, Prawns, veal bacon, cream cheese, panko, coriander, chipotle mayo mint leaves, fresh sugarcane juice, soda water KITCHENKITCHEN Picada Cubana (V)(G)(D) 98 Tostones, yuca frita, potato croquettes, black beans empanada, Cuba Libre 45 sweet potato flautas Rumba is not just a White rum, coca-cola, fresh lemon dance rhythm, it’s a juice, spices way of life. A lifestyle concept that OROORO VERDEVERDE embodies many shapes. From Guacamole Habanero 65 dining and bar experiences Smoked habanero chili, red onion, coriander, to lounge, cigar, terrace and lime, mix chips beach, Rumba erupts in a Guacamole Tradicional 59 spontaneous gathering of White onion, tomato, coriander, lime, mix chips lively colors, traditional Cuban cuisine and the syncopated Guacamole Rumba (D) 89 rhythms of music and dance. Skirt steak, manchego cheeese, green tomatillo, roasted zucchini seed, red onion, coriander, lime, mix chips CONVERT ANAKENA WHITE OR RED WINE TO SANGRIA 1 LITRE -

Proud Activist Kirsten Ussery Is Detroit Dynamo

FREE | SEPT. 29, 2011 | VOL. 1939 2011 | VOL. 29, | SEPT. EXCLUSIVE CHAT WITH FIrst OPENLY GAY BISHOP AIDS WALK MICHIGAN RAISES MORE THAN $100K GlorIA EstefAN TALKS TARGET GAFFE, NEW CD PROUD ACTIVIst COME OUT, KIrsteN USSERY IS DETROIT DYNAMO step UP PRIDESOURCE.COM 2 Between The Lines • September 29, 2011 9.29.2011 10 15 19 Cover story Life 6 | From closeted activist to Detroit dynamo 15 | Gloria Reaches Out to the Gays Kirsten Ussery urges people of In this exclusive chat, the Queen of Latin color to come out and step up Pop talks conservative upbringing, gay BTL photo: Andrew Potter marriage and Target controversy News 18 | ‘Ordinary’ gays in ‘extraordinary’ musical Relationships examined in new 5 | Speak Out Kalamazoo musical Progress is possible 19 | Hear Me Out 7 | First openly gay bishop talks death threats, Erasure succeeds with new sound. Plus: 9/11 Tori Amos’ best album in years 9 | Partner benefits for state employees 20 | Happenings Featured: Vienna Teng on Oct. 7 at could cost $600K The Power Center in Ann Arbor 11 | AIDS Walk Michigan raises more than 21 | Curtain Calls $100K Reviews of “Unlocking Desire” and “A Day in Hollywood/A Night in Ukraine” 12 | Police probe bullying after 14-year-old commits suicide 13 | State Equality Dinner award winners Rear View announced 22 | Dear Jody 23 | Horoscopes Opinions 24 | Puzzle 8 | BTL Editorial GOP’s argument against partner benefits is cheap 25 | Classifieds 8 | Thinking Out Loud Who are you calling a hater? 27 | Deep Inside Hollywood 10 | S/he said Politics, discrimination 10 | Heard on Facebook We’re sad to report that a New York teen who made an “It Gets Better” video committed suicide. -

The 1970S: Pluralization, Radicalization, and Homeland

ch4.qxd 10/11/1999 10:10 AM Page 84 CHAPTER 4 The 1970s: Pluralization, Radicalization, and Homeland As hopes of returning to Cuba faded, Cuban exiles became more con- cerned with life in the United States. Exile-related struggles were put on the back burner as more immediate immigrant issues emerged, such as the search for better jobs, education, and housing. Class divisions sharpened, and advocacy groups seeking improved social services emerged, including, for example, the Cuban National Planning Council, a group of Miami social workers and businesspeople formed in the early 1970s. As an orga- nization that provided services to needy exiles, this group de‹ed the pre- vailing notion that all exiles had made it in the United States. Life in the United States created new needs and interests that could only be resolved, at least in part, by entering the domestic political arena. Although there had always been ideological diversity within the Cuban émigré community, it was not until the 1970s that the political spec- trum ‹nally began to re›ect this outwardly.1 Two sharply divided camps emerged: exile oriented (focused on overthrowing the Cuban revolution- ary government) and immigrant oriented (focused on improving life in the United States). Those groups that were not preoccupied with the Cuban revolution met with hostility from those that were. Exile leaders felt threat- ened by organized activities that could be interpreted as an abandonment of the exile cause. For example, in 1974 a group of Cuban exile researchers conducted an extensive needs assessment of Cubans in the United States and concluded that particular sectors, such as the elderly and newly arrived immigrants, were in need of special intervention.2 When their ‹ndings were publicized, they were accused of betraying the community because of their concern with immigrant problems rather than the over- throw of the revolution. -

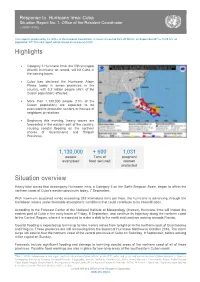

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

Documenting Cuban Exiles and the Cuban American Experience in South Florida Esperanza B

Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists Volume 17 | Number 1 Article 6 January 1999 Documenting Cuban Exiles and the Cuban American Experience in South Florida Esperanza B. de Varona University of Miami Diana Gonzalez Kirby University of Miami Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation de Varona, Esperanza B. and Kirby, Diana Gonzalez, "Documenting Cuban Exiles and the Cuban American Experience in South Florida," Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists 17 no. 1 (1999) . Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 85 Documenting Cuban Exiles and the Cuban Ameri can Experience in South Florida Esperanza B. de Varona and Diana Gonzalez Kirby When Fidel Castro rose to power on 1January1959, Cu bans left their Caribbean island in a mass exodus with hopes of returning in the near future. Miami, Florida's geographic loca tion made it the logical point of entry into the United States. Today, forty-two years after the triumph of the Cuban revolution, Miami-Dade County contains the largest concentration of Cu bans living in exile, approximately seven hundred thousand. With Hispanics comprising 49 percent of Miami-Dade County's popu lation, Cubans by far outnumber all other Hispanics and are a majority across more than half the county's residential areas.' Along with demographic growth and occupational mobility, many members of the Cuban American community made the Hispanic presence evident in local politics. -

The Cuban Exodus: Growing Complexity & Diversity

The Cuban Exodus: Growing Complexity & Diversity Jorge Duany Cuban Research Institute Florida International University Main Objectives Trace historical development of Cuban exodus Describe socioeconomic profile of each migrant stage Examine similarities & differences among “vintages” Analyze diverse views about U.S. policy toward Cuba Cuban Migration to the U.S., by Decade (Thousands) 400 300 200 100 0 Five Main Migrant Waves Post- Balsero Soviet Crisis Exodus Mariel (1995– ) Exodus (1994) Freedom • 549,013 Flights (1980) • 30,879 Golden persons persons Exiles (1965–73) • 124,779 persons (1959–62) • 260,561 • 248,070 persons persons The “Golden Exiles,” 1959–1962 Occupation of Cuban Refugees, 1959–62, & Cuban Population, 1953 (%) Professional, technical, & managerial Clerical & sales Skilled, semi-skilled, & unskilled Service Farm 0 15 30 45 Cuban refugees Cuban population Transforming Miami Operation Pedro Pan, 1960–62 The “Freedom Flights,” 1965–1973 Comparing the First & Second Waves of Cuban Refugees 1959–62 1965–73 Median age at arrival 40.4 40.2 (years) Female (%) 53.9 57.6 White (%) 98 96.9 Born in Havana (%) 62 63.2 High school graduates (%) 36 22 Professional & managerial 37 21 (%) “El Refugio,” 1967 Resettled Cuban Refugees, 1961–72 Elsewhere Pennsylvania Connecticut New York Texas Massachusett s Louisiana New Jersey Florida Illinois California The Mariel Exodus, 1980 A Marielito in a Refugee Camp Comparing 1980 & 1973 Cuban Refugees 1980 1973 Median age at arrival (years) 34 40.3 Single (%) 42.6 17.1 Black or mulatto (%) 12.6 3.1 Born in Havana (%) 48.4 41.1 Mean number of relatives at arrival 3.1 10.2 Average years of education in Cuba 9.1 8.6 No knowledge of English (%) 57.4 44.8 Professional & managerial in Cuba (%) 14 10 Current median earnings per month ($) 523 765 Cuban Migration to the U.S. -

Gloria Estefan the Standards Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gloria Estefan The Standards mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Pop Album: The Standards Country: Canada Released: 2013 Style: Vocal, Easy Listening MP3 version RAR size: 1279 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1579 mb WMA version RAR size: 1927 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 266 Other Formats: VQF MP2 AA MIDI AC3 DTS MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Good Morning Heartache 1 4:22 Music By, Lyrics By – Dan Fisher, Erwin Drake*, Irene Higginbotham They Can't Take That Away From Me 2 4:04 Music By, Lyrics By – Ira Gershwin And George Gershwin* What A Difference A Day Makes 3 3:42 Music By, Lyrics By – Maria Grever, Stanley Adams I've Grown Accustomed To His Face 4 4:11 Music By, Lyrics By – Frederick Loewe And Adam Jay Lerner* Eu Sei Que Vou Te Amar 5 3:37 Music By, Lyrics By – Antonio Carlos Jobim, Vinicius De Moraes The Day You Say You Love Me 6 Music By, Lyrics By – Alfredo Le Pera, Carlos GardelTranslated By [English Lyrics] – Gloria 4:55 Estefan Embraceable You 7 3:59 Music By, Lyrics By – Ira Gershwin And George Gershwin* What A Wonderful World 8 4:10 Music By, Lyrics By – Bob Thiele, George David Weiss How Long Has This Been Going On 9 4:15 Music By, Lyrics By – Ira Gershwin And George Gershwin* Sonríe (Duet With Laura Pausini) 10 Adapted By [Spanish Lyrics] – Gloria EstefanLyrics By – Geoffrey Parsons, John Turner 3:56 Music By – Charles Chaplin*Vocals [Duet With] – Laura Pausini The Way You Look Tonight 11 4:10 Lyrics By – Dorothy FieldsMusic By – Jerome Kern You Made Me Love You 12 4:02 Music By, Lyrics By – James V. -

Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms with Dreams and Dogmas Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected]

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 2003 Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms With Dreams and Dogmas Francisco Valdes University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Francisco Valdes, Diaspora and Deadlock, Miami and Havana: Coming to Terms With Dreams and Dogmas, 55 Fla.L.Rev. 283 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIASPORA AND DEADLOCK, MIAMI AND HAVANA: COMING TO TERMS WITH DREAMS AND DOGMAS Francisco Valdes* I. INTRODUCTION ............................. 283 A. Division and Corruption:Dueling Elites, the Battle of the Straits ...................................... 287 B. Arrogation and Class Distinctions: The Politics of Tyranny and Money ................................. 297 C. Global Circus, Domestic Division: Cubans as Sport and Spectacle ...................................... 300 D. Time and Imagination: Toward the Denied .............. 305 E. Broken Promisesand Bottom Lines: Human Rights, Cuban Rights ...................................... 310 F. Reconciliationand Reconstruction: Five LatCrit Exhortations ...................................... 313 II. CONCLUSION .......................................... 317 I. INTRODUCTION The low-key arrival of Elian Gonzalez in Miami on Thanksgiving Day 1999,1 and the custody-immigration controversy that then ensued shortly afterward,2 transfixed not only Miami and Havana but also the entire * Professor of Law and Co-Director, Center for Hispanic & Caribbean Legal Studies, University of Miami. -

Portal Del Periódico La Demajagua, Diario Digital De La Provincia De Granma. Portal of Newspaper La Demajagua, Digital Journal of Granma Province

Portal del periódico La Demajagua, Diario digital de la provincia de Granma. Portal of Newspaper La Demajagua, Digital Journal of Granma Province. Ing Leover Armando González Rodríguez Facultad Regional de Granma de la Universidad de las Ciencias Informáticas, Ave Camilo Cienfuegos, sin número, Manzanillo, Granma, Cuba. Ministerio de la Informática y las Comunicaciones Departamento de la Especialidad "Ing Leover Armando González Rodríguez" <[email protected]> Manzanillo, Granma, Cuba Junio de 2011 “Año 53 de la Revolución” Contenido Resumen: ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Abstract:................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introducción: ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Tipos de Prensa. ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Principales tecnologías utilizadas en el desarrollo del sistema. .............................................................................. 9 Lenguajes de programación: ............................................................................................................................. 9 Herramientas utilizadas ................................................................................................................................... -

Latino Louisiana Laź Aro Lima University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Faculty Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Publications 2008 Latino Louisiana Laź aro Lima University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lalis-faculty-publications Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Lima, Lazá ro. "Latino Louisiana." In Latino America: A State-by-State Encyclopedia, Volume 1: Alabama-Missouri, edited by Mark Overmyer-Velázquez, 347-61. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC., 2008. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American, Latino and Iberian Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19 LOUISIANA Lazaro Lima CHRONOLOGY 1814 After the British invade Louisiana, residents of the state from the Canary Islands, called Islenos, organize and establish three regiments. The Is/enos had very few weapons, and some served unarmed as the state provided no firearms. By the time the British were defeated, the Islenos had sustained the brunt of life and property loss resulting from the British invasion of Louisiana. 1838 The first. Mardi Gras parade takes place in New Orleans on Shrove Tuesday with the help and participation of native-born Latin Americans and Islenos. 1840s The Spanish-language press in New Orleans supersedes the state's French-language press in reach and distribution. 1846-1848 Louisiana-born Eusebio Juan Gomez, editor of the eminent Spanish language press newspaper La Patria, is nominated as General Winfield Scott's field interpreter during the Mexican-American War. -

Reporte Anual 2007

Annual Report 2007 5 years 2 Annual Report 2007 · Presentation he present report includes a summary of the main activities by the Center for the Opening and Development of Latin America (CADAL) organized during 2007: the events organized in Buenos Aires, Montevideo and TSantiago de Chile; Documents and Research Reports published during this period; the articles reproduced in diferent media outlets; and a selection of the most important Institutional News; and finally, some of the comments of the participants in the Seminar “Economic Information”. Regarding publications, CADAL edited 17 Documents, 9 Research Reports, 1 book and 21 interviews were done, 13 of which were published in a double page of the Sunday suplement El Observador of Perfil newspaper and one of them and the Sunday Suplement Séptimo Día of El Nuevo Herald newspaper. The complete version of the publications is available of the website of CADAL and many of them are also in English. Besides, during 2007 CADAL organized 32 events; 24 in Buenos Aires, 7 in Montevideo and 1 in Santiago de Chile, and 9 training meetings. A total of 77 different speakers took part, in the events and training meeting, . During last year CADAL registered over a hundred media mentions, the most important of which are: CNN en español in two opportunities (United States), Newsweek Magazine (United States), La Nación newspaper (Argentina), El Mercurio newspaper (Chile), SBTV (Brazil), Perfil newspaper (Argentina), El País newspaper (Uruguay), El Nuevo Herald newspaper (United States), Galería magazine -

HALL MEMORIAL LIBRARY ■ Monday, April 8 NH Native, Fred Johnson, Elizabeth Strout Chess Club, 4-7 P.M

THURSDAY, APRIL 4, 2013 SERVING TILTON, NORTHFIELD, BELMONT & SANBORNTON, N.H. FREE Downtown merchants air concerns with Tilton selectmen BY DONNA RHODES close at 5 p.m. and don’t open pick-up would be feasible. [email protected] again until 10 a.m., this cre- “I’d be skeptical of a mid- ates a hardship since Best- day pick-up with all the traf- TILTON — “This is about way Disposal Service picks fic along Main Street,” Allen anything and everything,” up trash on Main Street ear- said. said Tilton Select Board ly in the morning. Consentino presented the Chair Pat Consentino as she “The garbage is a big con- idea of consolidating trash opened a public hearing cern for us,” said Steve from the stores by designat- with business owners along Beaulieu, one of the owners ing a few collections sites Main Street last Thursday of Blooming Iris. “I’ve been along the street. That, she evening. bringing it home with me in- said, might make it easier After receiving an invita- stead, and that’s really not for businesses to comply tion to meet with the board, fair to the town I live in.” and collections to be made a handful of the merchants Selectmen agreed that in a quick and safe manner came to discuss issues business hours and traffic during the day. Business unique to their locations in on the busy street make owners who were present the busy downtown section trash collection a tough is- agreed that could be a viable of Tilton. sue to resolve.