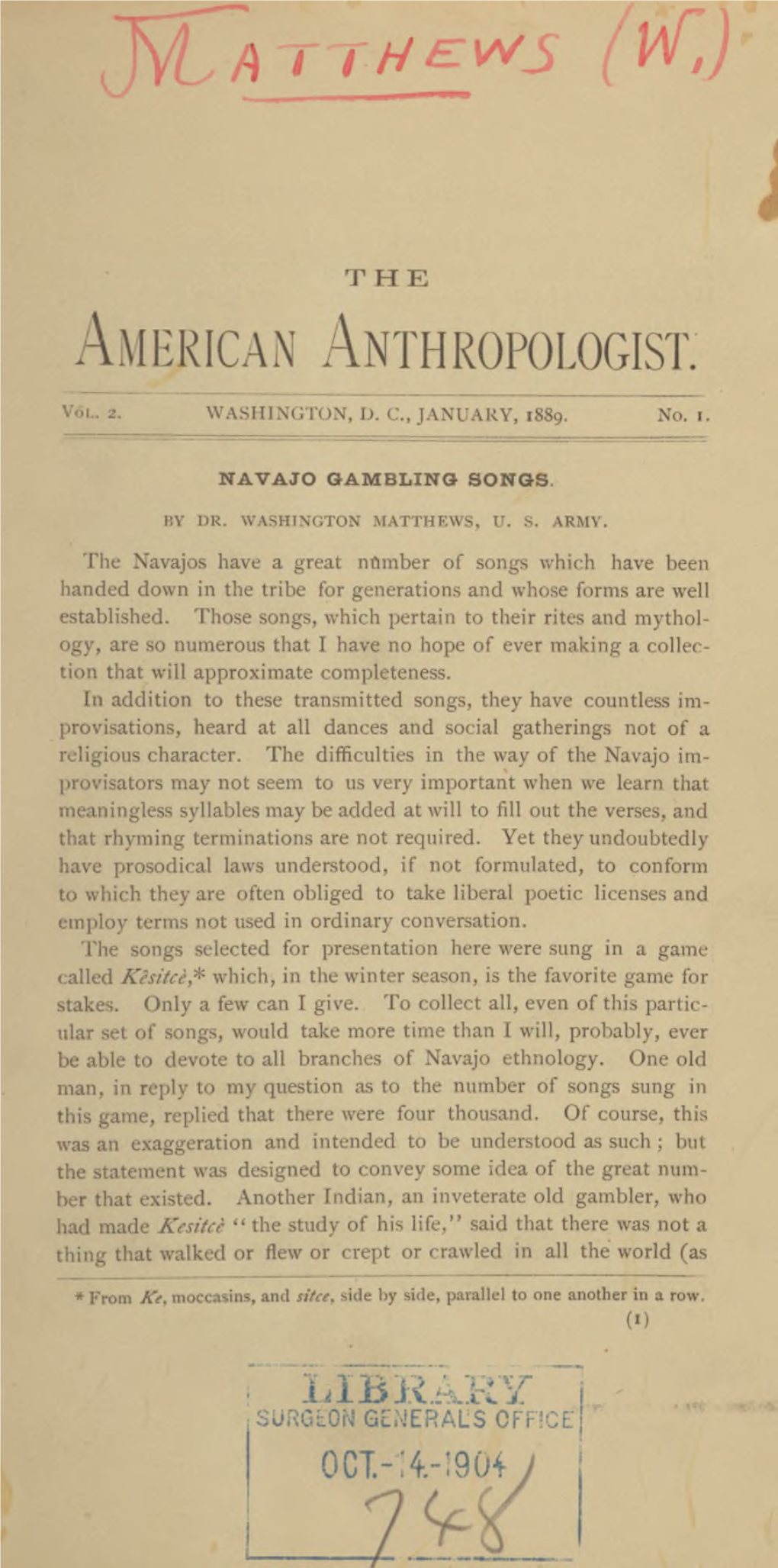

Navajo Gambling Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

“Who's Calling, Please?”

“Who's calling, please?” January 17, 2021, 10 a.m. ALL ARE WELCOME! Pilgrim Congregational UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST 2118 South Third Avenue Bozeman, Montana 59715 [email protected] http//www.uccbozeman.org (406) 587-3690 MISSION STATEMENT We come together to celebrate the seasons of Christian life and to welcome diverse people into community. We welcome all to share in the life and leadership, ministry, and fellowship, worship, sacraments, responsibilities and blessings of participation in our congregation. We covenant as God’s instruments to study and practice wisdom and compassion, to encourage the spiritual work of each individual for the sake of the world, and to perform joyfully and humbly acts of kindness and justice. We, Pilgrim Congregational United Church of Christ, declare ourselves to be open and affirming. With God’s grace, we seek to be a congregation that includes all persons, embracing differences of gender, marital status, sexual orientation, age, mental and physical ability, and racial, ethnic, or socio-economic backgrounds. Order of Service January 17, 2021 PRELUDE: “Contentment” by G. Ad. Thomas — Denny and Ilse-Mari Lee, piano duet ANNOUNCEMENTS AND GREETINGS: Wendy Morical, Moderator OPENING BELL CALL TO WORSHIP: (from Psalm 139) Leader: O God, you have searched me and known me. You know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from far away. PEOPLE: YOU SEARCH OUT MY PATH AND MY LYING DOWN, AND ARE ACQUAINTED WITH ALL MY WAYS. Leader: Even before a word is on my tongue, O LORD, you know it completely. PEOPLE: YOU HEM ME IN, BEHIND AND BEFORE, AND LAY YOUR HAND UPON ME. -

Driver's Licensing Handbook

DRIVER’SDRIVER’S LICENSING HANDBOOK STATE OF WEST VIRGINIA Revised 02/2021 DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES PO Box 17010 5707 MacCorkle Avenue, SE Charleston, WV 25317 Before you call, please have your license plate number, driver’s license number, and/or your file number ready so that we can assist you as quickly as possible. For Vehicle Title, License Plate, Driver’s License issues, or for General Information (304) 926‑3499 / (800) 642‑9066 | Hearing‑Impaired ‑ (800) 742‑6991 Other Important Telephone Numbers (Area Code 304) Driver’s License ................................................................................................. 926‑3801 Point System .................................................................................................... 926‑2505 Student Attendance ......................................................................................... 926‑2505 Unpaid Tickets .................................................................................................. 926‑2505 Driving Records ................................................................................................ 926‑3952 Compulsory Insurance ...................................................................................... 926‑3802 Driving Under the Influence .............................................................................. 926‑2506 Driving Under the Influence “Interlock” ............................................................ 926‑2507 Visit us on the web at dmv.wv.gov. Need help with reading -

THE SONG of the BIRD Anthony De Mello S

THE SONG OF THE BIRD Anthony de Mello S. J. This book has been written for people of every persuasion religious and non religious, I cannot, however, hide from my readers the fact that I am a priest of the Catholic Church. I have wandered free-ly in mystical traditions that are not Christian and not religious and I have been profoundly influenced by them. It is to my Church, however, that I keep returning, for she is my spiritual home; and while I am acutely, sometimes embarrassingly, conscious of her limitations and narrowness, I also know that it is she who has formed me and made me what I am today. So it is to her that I gratefully dedicate this book. Everyone loves stories and you will find plenty of them in this book: Stories that are Buddhist, Christian, Zen, Hasidic, Russian, Chinese, Hindu, Sufi; stories ancient and contemporary. And they all have a special quality: if read in a cer-tain kind of way, they will produce spiritual growth. HOW TO READ THEM There are three ways: 1. Read a story once. Then move on to another. This manner of reading will give you entertainment. 2. Read a story twice. Reflect on it. Apply it to your life. That will give you a taste of theology. This sort of thing can be fruitfully done in a group where the members share their reflections on the story. You then have a theological circle. 3. Read the story again, after you have reflected on it. Create a silence within you and let the story reveal to you its inner depth and meaning: something beyond words and reflections. -

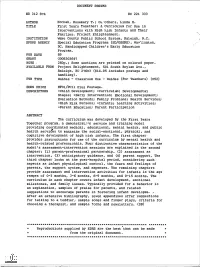

ED312874.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 312 874 EC 221 333 AUTHOR Hornak, Rosemary T.; CE-others, Linda H. TITLE First Years Together: A Curriculum for Use in Interventions with High Lisk Infants and Their Families. Project Enlightenment. INSTITUTION Wake County Public School System, Raleigh, N.C. SPONS AGENCY Special Education Programs (ED/OSERS), Was%ington, DC. Handicapped Children's Early Education Program. PUB DATE 89 GRANT 3008303647 NOTE. 260p.; Some sections are printed on colored paper. AVAILABLE FROM Project Enlightenment, 501 South Boylan Ave., Raleigh, NC 27603 ($14.95 includes postage and handling). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Child Development; *Curriculum; Developmental Stages; *Early Intervention; Emotional Development; Evaluation Methods; Family Problems; Health Services; *High Risk Persons; *Infants; Learning Activities; *Parent Education; Parent Participation ABSTRACT The curriculum was developed by the First Years Together program, a demonstrat!'ln service and training model providing coordinated medical, educational, mental health, and public health servicres to maximize the social-emotional, physical, and cognitive development of high risk infants. The first chapter provides instructions for use of the curriculum by mental health and health-related professionals. Four distinctive characteristics of the model's assessment-intervention sessions are explained in the second chapter: (1) parent-professional partnership, (2) assessment as intervention, (3) anticipatory guidance, and (4) parent support. The third chapter looks at the post-hospital period, considering such aspects as infant physiological control, the fears and feelings of parents, the support system, and expenses. The remaining chapters provide assessment and intervention activities for infants in the age ranges of 0-3 months, 3-6 months, 6-9 months, and 9-15 months. -

Preview Sound Generation (PDF)

SOUND GENERATION 5IF3FTPOBOU7PJDFTPG5FFO(JSMT A WriteGirl Publication ALSO FROM WRITEGIRL PUBLICATIONS Emotional Map of Los Angeles: Creative Voices from WriteGirl You Are Here: The WriteGirl Journey No Character Limit: Truth & Fiction from WriteGirl Intensity: The 10th Anniversary Anthology from WriteGirl Beyond Words: The Creative Voices of WriteGirl Silhouette: Bold Lines & Voices from WriteGirl Lines of Velocity: Words that Move from WriteGirl Untangled: Stories & Poetry from the Women and Girls of WriteGirl Nothing Held Back: Truth & Fiction from WriteGirl Pieces of Me: The Voices of WriteGirl Bold Ink: Collected Voices of Women and Girls Threads Pens on Fire: Creative Writing Experiments for Teens from WriteGirl (Curriculum Guide) IN-SCHOOLS PROGRAM ANTHOLOGIES Unstoppable: Creative Voices of the WriteGirl & Bold Ink Writers In-Schools Programs These Moments: The Creative Voices of the WriteGirl In-Schools Program Ocean of Words: Bold Voices from the WriteGirl In-Schools Program Words & Curiosity: Creative Voices of the WriteGirl In-Schools Program This Is My World: Creative Voices of the WriteGirl In-Schools Program Ready for the Next Chapter: Creative Voices of the WriteGirl In-Schools Program No Matter What: Creative Voices from the WriteGirl In-Schools Program So Much to Say: The Creative Voices of the WriteGirl In-Schools Program Sound of My Voice: Bold Words from the WriteGirl In-Schools Program This Is Our Space: Bold Words from the WriteGirl In-Schools Program Ocean of Words: Bold Voices from the WriteGirl In-Schools Program -

Celine Dion in Concert

Celine Dion in Concert UK and Ireland Tour – 11 – 27 April 2021 TOUR DATES 2021 UK & Ireland Dates: 11 April - Dublin 12 April - Dublin 15 April - Manchester 16 April - Manchester 19 April - Birmingham 20 April - Birmingham Celine Dion is an international popstar selling more 22 April - London than 100 million albums worldwide. Her career has spanned years of superstardom during the 1990s, as 23 April - London well as several multi-year residencies at Caesars 26 April - Glasgow Palace in Las Vegas. 27 April - Glasgow Dion won the 1988 Eurovision Song Contest, representing Switzerland, and her hits include Think More dates/venues Twice, Because You Loved Me and the timeless My available. Get in touch for Heart Will Go On, the Academy Award-winning song more information: [email protected] from the movie, Titanic. Her Courage World Tour supports Dion’s first English album in six years and will see the global megastar return following her phenomenal headline slot at British Summer Time, Hyde Park. Tracks such as Imperfections, Lying Down and Courage represent an exciting new creative direction for her and fans will have a chance to hear songs from the new album on her tour. Buy Tickets & VIP Hospitality now. Now is an ideal time to book your tickets and/or VIP Hospitality Packages to see this year's tour live at your favourite venues. CONTACT US With over 40 years’ experience in the hospitality and live events industries, we regularly make arrangement on behalf of our clients in For further information, providing VIP Corporate Hospitality -

View Spiritual Verses and Prayers

Spiritual Verses and Prayers Psalm 23 – Oxford Version Christian Psalm 23 Christian The Lord is my shepherd; there is nothing I shall want. The LORD is my shepherd, Fresh and green are the pastures I shall not want. where he gives me repose, He makes me lie down in green pastures; Near restful waters he leads me He leads me beside quiet waters. to revive my drooping spirit. He restores my soul; He guides me in the paths He guides me along the right path; of righteousness For His name's sake. he is true to his name. Even though I walk through If I should walk in the valley of darkness the valley of the shadow of death, no evil would I fear. I fear no evil, for You are with me; You are there with your crook and your staff; Your rod and Your staff, with these you give me comfort. they comfort me. You prepare a table before me You have prepared a banquet for me in the presence of my enemies; in the sight of my foes. You have anointed my head with oil; My head you have anointed with oil; My cup overflows. my cup is overflowing. Surely goodness and loving Surely goodness and kindness shall follow me kindness will follow me all the all the days of my life. days of my life, In the Lord’s own house shall I dwell And I will dwell in the house for ever and ever. of the LORD forever. Psalm 34:1-10 Christian Psalm 23 - A Psalm of David I will thank the LORD at all times. -

Afro-American Folk Music from Tate and Panola Counties, Mississippi

Folk Music of the United States Music Division Recording Laboratory AFS L67 Afro-American Folk Music from Tate and Panola Counties, Mississippi From the Archive of Folk Song Edited by David Evans ' I' : : '7' .. - ~ -' -. Library of Congress Washington De Soto Co. Arkabutla Lake Marshall r---tt__----!.!!~_--lindepe Co. Sardis Lake Quitman Lafayette Co. Co. Tallahatchie Yalobusha Co. Co. SCALE OF MILES o 5 10 15 I I I I Preface TATE AND PANOLA COUNTIES are in the northwestern part of the state The economy of the area is heavily agricultural, especially for the of Mississippi, due south of Memphis, Tennessee. Coldwater, the northern black population. In former times the main crop was cotton, and much most town in Tate County, is thirty miles from downtown Memphis, and of the land was worked by black sharecroppers. This pattern has changed from there it is another thirty-five miles to the southern edge of Panola considerably since cotton prices went down and agriculture became mecha County. Running north and south, U .S. Highway 51 bisects the two nized. Now much of the land is planted with corn and soybeans, although counties and was formerly the main artery of travel. Along it are the main cotton is still an important crop. Some large landowners have turned to towns, Coldwater and Senatobia in Tate, and Como, Sardis, Batesville, cattle grazing. The few black workers left on the large farms are living Courtland, and Pope in Panola. Senatobia is the Tate county seat, and there because of the indulgence of the owners, because the house rent is Sardis and Batesville are the joint seats of Panola County. -

The Song School

The Song School August 1-5, 2021 • Lyons, CO Schedule and Course Descriptions Sunday, August 1 st TO DO LIST: ● Sign up for the open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime on Monday in the Blue Heron Tent. (Registration Tent) ● Check master roster information at the registration desk for accuracy. 1:00 Campgrounds Opens 3:00 - 5:00 Student Registration Visit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, Song School laminate, hat and other goodies. 5:30 - 6:00 New Student Meet and Greet - Wildflower Pavilion First timer? Meet up with Song School veterans, an instructor or two, ask that burning question, and get some sage advice on how to make your week enjoyable. Monday, August 2 nd TO DO LIST: ● Sign up by 9:15am for the open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime today in the Blue Heron Tent. ● Check master roster information at the registration desk for accuracy. ● Mentoring sheets will go out at 9am each morning for that day’s mentoring sessions. 7:30 - 8:15 Qi Gong Qi Gong is a 4,000 year old practice that cultivates energy and vitality. Practice gentle movements with certified instructor Carli Zug that strengthen the body, increase flexibility and relieve stress. No prior experience necessary, just comfortable clothes. (Trout Tent) Monday p. 2 8:00 - 9:15 Student Registration V isit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, Song School laminate, hat and other goodies. Help yourself to tea or coffee and fruit and muffins next door at the beverage area. -

Titanique Captions

>> SIT BACK, RELAX. YOUR STELLAR STREAM IS ABOUT TO BEGIN. [MUSIC] >> YOU'RE WATCHING STELLAR. WELCOME TO TITANIQUE: THE MAIDEN VOYAGE CONCERT AT LE POISSON ROUGE! I’M KYLE FREEMAN AND I’LL BE YOUR TOUR GUIDE. AS YOU ALL KNOW, THE PAST YEAR AND A HALF HAS BEEN AN UTTER SHIT SHOW. SO WE THOUGHT, WHY NOT MAKE IT A MUSICAL SHIT SHOW. WHILE THE PANDEMIC MAY HAVE RE-CHARTED TITANIQUE’S COURSE, IT HAS NOT SUNK OUR SHIP OF DREAMS. SO TONIGHT, WE ARE LIVE, HONEY! [APPLAUSE] OUR AUDIENCE HERE IS SMALL AS HELL BUT THEY'RE MIGHTY. FOR THOSE OF YOU WATCHING AT HOME, CHAT WITH US ON THE STELLAR APP, DRINK LIKE SAILORS, AND SHOWER US WITH APPLAUSE FROM NEAR, FAR...WHEREVER YOU ARE. ANYWAY, I GOTTA GET TO THE SHOW - HAVE FUN GIRLFRIENDS! [APPLAUSE] [MUSIC] [PIANO] [MUSIC]. >> A NEW DAY, AHH. >> A NEW DAY, AHH. WELCOME TO THE TITANIC MUSEUM. PLEASE, HAVE A LOOK AROUND. YOU'LL SEE ARTIFACTS FROM ONE OF THE GREATEST TRAGEDIES IN AMERICAN HISTORY. >> AH! >> AH! MMM... >> OVER HERE YOU'LL FIND A VINTAGE MONOCLE WORN BY THE SHIP'S CAPTAIN. HE HAD LIKE...REALLY BAD EYESIGHT. >> AH! AH! MMM.... >> AND HERE YOU'LL FIND AN ACRYLIC PORTRAIT OF A CHILD HOLDING A DAISY IN ONE HAND AND A MACHETE IN THE OTHER. >> AH! AH! MMM…. >> AND OVER HERE YOU'LL FIND MY EX BOYFRIEND, BRIAN. BRIAN, WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU DOING HERE? YOU LOOK DAMN FINE THOUGH. MMMM. I WANT TO TAKE A BITE OUT OF THAT. [LAUGHTER] I LOVE YOU, BRIAN. -

SONG of SONGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza

SONG OF SONGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza Editorial Board Mary Ann Beavis Carol J. Dempsey Amy-Jill Levine Linda M. Maloney Ahida Pilarski Sarah Tanzer Lauress Wilkins Lawrence Seung Ai Yang WISDOM COMMENTARY Volume 25 Song of Songs F. Scott Spencer Lauress Wilkins Lawrence Volume Editor Barbara E. Reid, OP General Editor A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Ann Blattner. Chapter Letter ‘W’, Acts of the Apostles, Chapter 4, Donald Jackson, Copyright 2002, The Saint John’s Bible, Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. © 2017 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Spencer, F. Scott (Franklin Scott), author. Title: Song of Songs / F. Scott Spencer ; Lauress Wilkins Lawrence, volume editor ; Barbara E. Reid, OP, general editor. Description: Collegeville, Minnesota : Liturgical Press, 2016.