PDF (Volume 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DANCING DAY MUSIC FORCHRISTMAS FIFTH AVENUE,NEWYORK JOHN SCOTT CONDUCTOR Matthew Martin (B

DANCING DAY MUSIC FOR CHRISTMAS SAINT THOMAS CHOIR OF MEN & BOYS, FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK JOHN SCOTT CONDUCTOR RES10158 Matthew Martin (b. 1976) John Rutter (b. 1945) Dancing Day 1. Novo profusi gaudio [3:36] Dancing Day Part 1 Music for Christmas Patrick Hadley (1899-1973) 17. Prelude [3:35] 2. I sing of a maiden [2:55] 18. Angelus ad virginem [1:55] 19. A virgin most pure [5:04] Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) 20. Personent hodie [1:57] A Ceremony of Carols, Op. 28 Part 2 Saint Thomas Choir of Men & Boys, Fifth Avenue, New York 3. Procession [1:32] 21. Interlude [4:05] 4. Wolcum Yole! [1:24] 22. There is no rose [1:53] 3-15 & 17-24 5. There is no Rose [2:26] 23. Coventry Carol [3:54] Sara Cutler harp [1:46] 1 & 16 6. That yonge child 24. Tomorrow shall be my Stephen Buzard organ 7. Balulalow [1:21] dancing day [3:03] Benjamin Sheen organ 2 & 25-26 8. As dew in Aprille [1:02] 9. This little babe [1:30] Traditional English 10. Interlude [3:32] arr. Philip Ledger (1937-2012) John Scott conductor 11. In Freezing Winter Night [3:50] 25. On Christmas Night [2:00] 12. Spring Carol [1:14] (Sussex Carol) 13. Adam lay i-bounden [1:12] 14. Recession [1:37] William Mathias (1934-1992) [1:41] 26. Wassail Carol Benjamin Britten 15. A New Year Carol [2:19] Total playing time [63:58] Traditional Dutch arr. John Scott (b. 1956) About the Saint Thomas Choir of Men & Boys: 16. -

Paul Lewis in Recital a Feast of Piano Masterpieces

PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL A FEAST OF PIANO MASTERPIECES SAT 14 SEP 2019 QUEENSLAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA STUDIO PROGRAM | PAUL LEWIS IN RECITAL I WELCOME Welcome to this evening’s recital. I have been honoured to join Queensland Symphony Orchestra this year as their Artist-in- Residence, and am delighted to perform for you tonight. This intimate studio is a perfect setting for a recital, and I very much hope you will enjoy it. The first work on the program is Haydn’s Piano Sonata in E minor. Haydn is well known for his string quartets but he also wrote a great number of piano sonatas, and this one is a particular gem. It showcases the composer’s skill of creating interesting variations of simple musical material. The Three Intermezzi Op.117 are some of Brahms’s saddest and most heartfelt piano pieces. The first Intermezzo was influenced by a Scottish lullaby,Lady Anne Bothwell’s Lament, and was described by Brahms as a ‘lullaby to my sorrows’. This is Brahms in his most introspective mood, with quietly anguished harmonies and dynamic markings that rarely rise above mezzo piano. Finally, tonight’s recital concludes with one of the great peaks of the piano repertoire. The 33 Variations in C on a Waltz by Diabelli is one of Beethoven’s most extreme and all- encompassing works – an unforgettable journey for the listener as much as the performer. Thank you for your attendance this evening and I hope you enjoy the performance. Paul Lewis 2019 Artist-in-Residence IN THIS CONCERT PROGRAM Piano Paul Lewis Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, Hob XVI:34 Brahms Three Intermezzi, Op.117 INTERVAL Approx. -

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No

'Koanga' and Its Libretto William Randel Music & Letters, Vol. 52, No. 2. (Apr., 1971), pp. 141-156. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0027-4224%28197104%2952%3A2%3C141%3A%27AIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-B Music & Letters is currently published by Oxford University Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/oup.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 22 12:08:38 2007 'KOANGA' AND ITS LIBRETTO FREDERICKDELIUS arrived in the United States in 1884, four years after 'The Grandissimes' was issued as a book, following its serial run in Scribner's Monthh. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Mellon Grand Classics Season April 23, 2017 MANFRED MARIA HONECK, CONDUCTOR TILL FELLNER, PIANO FRANZ SCHUBERT Selections from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 I. Overture II. Ballet Music No. 2 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra in C minor, Opus 37 I. Allegro con brio II. Largo III. Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner Intermission WOLFGANG AMADEUS Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, “Jupiter” MOZART I. Allegro vivace II. Andante cantabile III. Allegretto IV. Molto allegro PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA FRANZ SCHUBERT Overture and Ballet Music No. 2 from the Incidental Music to Rosamunde, D. 644 (1820 and 1823) Franz Schubert was born in Vienna on January 31, 1797, and died there on November 19, 1828. He composed the music for Rosamunde during the years 1820 and 1823. The ballet was premiered in Vienna on December 20, 1823 at the Theater-an-der-Wein, with the composer conducting. The Incidental Music to Rosamunde was first performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony on November 9, 1906, conducted by Emil Paur at Carnegie Music Hall. Most recently, Lorin Maazel conducted the Overture to Rosamunde on March 14, 1986. The score calls for pairs of woodwinds, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings. Performance tine: approximately 17 minutes Schubert wrote more for the stage than is commonly realized. His output contains over a dozen works for the theater, including eight complete operas and operettas. Every one flopped. Still, he doggedly followed each new theatrical opportunity that came his way. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Kalendár Výročí

Č KALENDÁR VÝROČÍ 2010 H U D B A Zostavila Mgr. Dana Drličková Bratislava 2009 Pouţité skratky: n. = narodil sa u. = umrel výr.n. = výročie narodenia výr.ú. = výročie úmrtia 3 Ú v o d 6.9.2007 oznámili svetové agentúry, ţe zomrel Luciano Pavarotti. A hudobný svet stŕpol… Muţ, ktorý sa narodil ako syn pekára a zomrel ako hudobná superstar. Muţ, ktorého svetová popularita nepramenila len z jeho výnimočného tenoru, za ktorý si vyslúţil označenie „kráľ vysokého cé“. Jeho zásluhou sa opera ako okrajový ţáner predrala do povedomia miliónov poslucháčov. Exkluzívny svet klasickej hudby priblíţil širokému publiku vystúpeniami v športových halách, účinkovaním s osobnosťami popmusik, či rocku a charitatívnymi koncertami. Spieval takmer výhradne taliansky repertoár, debutoval roku 1961 v úlohe Rudolfa v Pucciniho Bohéme na scéne Teatro Municipal v Reggio Emilia. Jeho ľudská tvár otvárala srdcia poslucháčov: bol milovníkom dobrého jedla, futbalu, koní, pekného oblečenia a tieţ obstojný maliar. Bol poverčivý – musel mať na vystú- peniach vţdy bielu vreckovku v ruke a zahnutý klinec vo vrecku. V nastupujúcom roku by sa bol doţil 75. narodenín. Luciano Pavarotti patrí medzi najväčších tenoristov všetkých čias a je jednou z mnohých osobností, ktorých výročia si budeme v roku 2010 pripomínať. Nedá sa v úvode venovať detailnejšie ţiadnemu z nich, to ani nie je cieľom tejto publikácie. Ţivoty mnohých pripomínajú román, ľudské vlastnosti snúbiace sa s géniom talentu, nie vţdy v ideálnom pomere. Ale to je uţ úlohou muzikológov, či licenciou spisovateľov, spracovať osudy osobností hudby aj z tých, zdanlivo odvrátených stránok pohľadu ... V predkladanom Kalendári výročí uţ tradične upozorňujeme na výročia narodenia či úmrtia hudobných osobností : hudobných skladateľov, dirigentov, interprétov, teoretikov, pedagógov, muzikológov, nástrojárov, folkloristov a ďalších. -

Music This Table Outlines What Can Be Found Within Musical Archival Collections in Edinburgh Which Are Relevant to Either Jewish

Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers as well as linking to a variety of additional subject matters. Repository Date Title Relevance Scope Reference National Library of 1781 Scottish Tragic Ballads Jewish literary Printed collection of Glen collection Scotland representation within musical ballad lyrics Shelfmark: Glen 140 a ballad in the collection entitled ‘the Jew’ National Library of 1806 Oliver’s collection of Ballad entitled ‘The Printed collection of Glen.5(1-4) Scotland comic songs’ Jew Peddler’ musical ballad lyrics Edinburgh University 1890-1900 Correspondence between Musician: Professional GB 237 Coll-411/1/L85 Archives Joseph Joachim and Sir Joseph Joachim correspondence; music Donald F. Tovey, Francis composition discussion; John Henry Jenkins, Sir concert dates; social Hubert Parry and Sophie niceties Weisse Edinburgh University 1892 and 1940 Letters between Sophie Musicians: One letter which GB 237 Coll 411/1/L2041 Archives Weisse, Sir Donald Tovey Fanny Behrens mentions Fanny Behrens and Fanny Behrens (wife Gustav Behrens between Tovey and of Gustav Behrens) Sophie Weisse; Second Letter from Behrens to Weisse alerting Miss. Weisse to an article about Tovey's 'absolute ear', news of Behrens recovery and of her sons Music This table outlines what can be found within musical archival collections in Edinburgh which are relevant to either Jewish representation, Jewish musicians or composers -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Willow-Wood the Sons of Light Toward the Unknown Region Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus

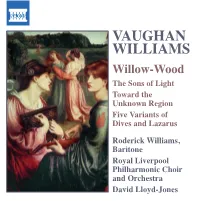

557798bk VW US 14/9/05 3:51 pm Page 12 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Willow-Wood The Sons of Light Toward the Unknown Region Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Roderick Williams, Baritone Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra David Lloyd-Jones 557798bk VW US 14/9/05 3:51 pm Page 2 Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) from the deep thought wherein he slept Light shall be light for ever and the darkness night, Willow-Wood • Toward the Unknown Region • The Sons of Light still two days younger than the morning star. Man shall awake and speak their names aloud This is the morning of the sons of light, and set a name on fire and wind and cloud The poems of the American Walt Whitman (1819-1892) into his score when he looks to the psalm tune Sine rejoice because they start upon their way; from whence all living creatures take delight. were published in Leaves of Grass, a collected works Nomine ‘and reaches a blazing climax in the final bars, singing they go, each clothed in his own day, Rejoice, man .stands among the sons of light. which in successive editions over 35 years from 1855 emblematic of the ultimate triumph of the soul’s destiny’. their orbits span the terrors of the height, added new poems at each appearance. Vaughan Williams The cantata Willow-Wood for baritone, women’s swifter than wind, as swift as thought, their flight. may have been first introduced to Whitman by his teacher voices and orchestra first appeared as a scena for baritone Stanford, who in his pioneering Elegiac Ode of 1884 had and piano in March 1903 when it was sung by Campbell Sing and rejoice, vast darkness, that you share been the first significant British composer to respond to McInnes in a concert at St James’s Hall, Piccadilly. -

Frederic Hymen Cowen (B

Frederic Hymen Cowen (b. Kingston, Jamaica, 29 January 1852; d. 6 October 1935, London) Concertstück for piano and orchestra Preface Frederic Cowen was born at Kingston, Jamaica, moving to London when his father became treasurer of Her Majesty’s Opera and subsequently of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Frederic showed an early aptitude for music, being encoura- ged by Sir Henry Bishop, taking lessons with John Goss and Julius Benedict, before eventually studying at Leipzig and Berlin with Ignaz Moscheles, Carl Reinecke, Louis Plaidy and Friedrich Kiel. His career was to be mainly as a conductor, notably of the Royal Philharmonic Society, the Halle, Liverpool Philharmonic and Scottish orchestras, and of the Handel Triennial Festival. It was through his conducting that Cowen became acquainted with Liszt, Rubinstein, Brahms, Grieg, Dvořák and many other contemporary musicians. As a composer, he achieved most success with his songs (more than 300 of them) and choral works, but he regarded his six symphonies as the pinnacle of his output. The Third Symphony (“The Scandanavian”) was his most successful (MPH score 749) and all six show a comfort with large structures, as well as a genuine flair for orchestration. That said, none could be said to be ‘forward looking’, and each is a good example of a post-Mendelssohn, post-Schumann European symphony. Cowen was a good enough pianist to play the Mendelssohn’s D minor Piano Concerto in public at the age of twelve. Following his studies in Leipzig and Berlin, he began a career as a pianist, touring the UK, Europe, and the USA. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1953-54

Contemporary Art Society Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, Millbank, S.W.I Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Executive Committee Raymond Mortimer, Chairman Sir Colin Anderson, Hon. Treasurer E. C. Gregory, Hon. Secretary Edward Le Bas, R.A. Sir Philip Hendy W. A. Evill Eardley Knollys Hugo Pitman Howard Bliss Mrs. Cazalet Keir Loraine Conran Sir John Rothenstein, C.B.E. Eric Newton Peter Meyer Assistant Secretary Denis Mathews Hon. Assistant Secretary Pauline Vogelpoel Annual Report 19534 Contents The Chairman's Report Acquisitions, Loans and Presentations The Hon. Treasurer's Report Auditor's Accounts Future Occasions Bankers Orders and Deeds of Covenant 10 Oft sJT CD -a CD as r— ««? _s= CO CO "ecd CO CO CD eds tcS_ O CO as. ••w •+-» ed bT CD ss_ O SE -o o S ed cc es ed E i Gha e th y b h Speec This year the Society can boast of having been more active than privileged to visit the private collections of Captain Ernest ever before in its history. We have, alas, not received by donation Duveen, Mrs. Edward Hulton, Mrs. Oliver Parker and Mrs. Lucy or legacy any great coliection of pictures or a nice, fat sum of Wertheim. We have been guests also at a number of parties, for money. Sixty members have definitely abandoned us, and a good which we have to thank the Marlborough Fine Art Ltd., (who many others, you will be surprised to hear, have without resigning, have entertained us twice), the Redfern Gallery, Messrs. omitted to pay their subscription. -

British Orchestral Music

BRITISH ORCHESTRAL MUSIC (Including Orchestral Poems, Suites, Serenades, Variations, Rhapsodies, Concerto Overtures etc) Written by Composers Born Between 1800 & 1910 A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers C-G WALTER CARROLL (1869-1955) Born in Manchester. He got his musical degrees at the Universities of Durham and Manchester and went on to an acdemic career at the University of Manchester and at the Royal Manchester College of Music. He became Music Dvisor to the City of Manchester and devoted himself to reforming and improving art education in the schools. With this goal in mind he composed piano music for children as well as instructional books. His enormous academic load precluded much time for other composing. Festive Overture (c. 1900) Gavin Sutherland/Royal Ballet Sinfonia ( + Blezard: Caramba, Black: Overture to a Costume Comedy, Langley: Overture and Beginners , Dunhill: Tantivy Towers, Chappel: Boy Wizard, Hurd: Overture to an Unwritten Comedy, Monckton: The Arcadians. Lane: A Spa Overture, Pitfield: Concert Overture and Lewis: Sussex Symphony Overture) WHITELINE CD WHL 2133 (2002) ADAM CARSE (1878-1958) Born in Newcastle-on-Tyne. He studied under Frederick Corder at the Royal Academy and later went on to teach at that school. He composed in various genres and his orchestral output includes 2 Symphonies, the symphonic poems "The Death of Tintagiles" and "In a Balcony," a Concert Overture and Variations for Orchestra. He also wrote musical textbooks that kept his name in print long after his compositions were forgotten. The Willow Suite for String Orchestra (1933) Gavin Sutherland/Royal Ballet Sinfonia ( +Purcell/Britten: Chacony, Lewis: Rosa Mundi, Warlock/Lane: Bethlehem Down, Holst: Moorside Suite, Carr: A Very English Music, W.