Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware of False Shepherds, Warhs Hem. Cardinal

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Principals in Pallium Ceremony i * BEWARE OF FALSE SHEPHERDS, % WARHS HEM. CARDINAL STRITCH Contonto Copjrrighted by the Catholic Preas Society, Inc. 1946— Pemiosion to reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marke^ given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Traces Catastrophes DENVER OONOLIC Of Modern Society To Godless Leaders I ^ G I S T E R Sermon al Pallium Ceremony in Denver Cathe The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We dral Shows How Archbishop Shares in Have Also the International Nows Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) True Pastoral Office VOL. XU. No. 35. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, A PR IL 25, 1946. $1 PER YEAR Beware of false shepherds who scoff at God, call morality a mere human convention, and use tyranny and persecution as their staff. There is more than a mere state ment of truth in the words of Christ: “I am the Good Shep Official Translation of Bulls herd.” There is a challenge. Other shepherds offer to lead men through life but lead men astray. Christ is the only shepherd. Faithfully He leads men to God. This striking comparison of shepherds is the theme Erecting Archdiocese Is Given of the sermon by H. Em. Cardinal Samuel A. Stritch of Chicago in the Solemn Pon + ' + + tifical Mass in the Deliver Ca An official translation of the PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE rate, first of all, the Diocese of thedral this Thursday morning, Papal Bulls setting up the Arch EVENT Denver, together with its clergy April 25, at which the sacred pal diocese of Denver in 1941 was The things that seem to be more and people, from the Province of lium is being conferred upon Arch Bishop Lauds released this week by the Most helpful in procuring the greater Santa Fe. -

Cardinal Cajetan Renaissance Man

CARDINAL CAJETAN RENAISSANCE MAN William Seaver, O.P. {)T WAS A PORTENT of things to come that St. Thomas J Aquinas' principal achievement-a brilliant synthesis of faith and reason-aroused feelings of irritation and confusion in most of his contemporaries. But whatever their personal sentiments, it was altogether too imposing, too massive, to be ignored. Those committed to established ways of thought were startled by the revolutionary character of his theological entente. William of la Mare, a representa tive of the Augustinian tradition, is typical of those who instinctively attacked St. Thomas because of the novel sound of his ideas without taking time out to understand him. And the Dominicans who rushed to the ramparts to vindicate a distinguished brother were, as often as not, too busy fighting to be able even to attempt a stone by stone ex amination of the citadel they were defending. Inevitably, it has taken many centuries and many great minds to measure off the height and depth of his theological and philosophical productions-but men were ill-disposed to wait. Older loyalities, even in Thomas' own Order, yielded but slowly, if at all, and in the midst of the confusion and hesitation new minds were fashioning the via moderna. Tempier and Kilwardby's official condemnation in 1277 of philosophy's real or supposed efforts to usurp theology's function made men diffident of proving too much by sheer reason. Scotism now tended to replace demonstrative proofs with dialectical ones, and with Ockham logic and a spirit of analysis de cisively supplant metaphysics and all attempts at an organic fusion between the two disciplines. -

Father William Peter Macdonald, a Scottish Defender of the Catholic Faith in Upper Canada Stewart D

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 01:41 Sessions d'étude - Société canadienne d'histoire de l'Église catholique "The Sword in the Bishop's Hand": Father William Peter MacDonald, A Scottish Defender of the Catholic Faith in Upper Canada Stewart D. Gill Bilan de l’histoire religieuse au Canada Canadian Catholic History: A survey Volume 50, numéro 2, 1983 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1007215ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1007215ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Les Éditions Historia Ecclesiæ Catholicæ Canadensis Inc. ISSN 0318-6172 (imprimé) 1927-7067 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Gill, S. D. (1983). "The Sword in the Bishop's Hand": Father William Peter MacDonald, A Scottish Defender of the Catholic Faith in Upper Canada. Sessions d'étude - Société canadienne d'histoire de l'Église catholique, 50(2), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.7202/1007215ar Tous droits réservés © Les Éditions Historia Ecclesiæ Catholicæ Canadensis Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des Inc., 1983 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ CCHA. Study Sessions, 50, 1983, pp. 437-452 "The Sword in the Bishop's Hand": Father William Peter MacDonald, A Scottish Defender of the Catholic Faith in Upper Canada * by Stewart D. -

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome

The Hospital and Church of the Schiavoni / Illyrian Confraternity in Early Modern Rome Jasenka Gudelj* Summary: Slavic people from South-Eastern Europe immigrated to Italy throughout the Early Modern period and organized them- selves into confraternities based on common origin and language. This article analyses the role of the images and architecture of the “national” church and hospital of the Schiavoni or Illyrian com- munity in Rome in the fashioning and management of their con- fraternity, which played a pivotal role in the self-definition of the Schiavoni in Italy and also served as an expression of papal for- eign policy in the Balkans. Schiavoni / Illyrians in Early Modern Italy and their confraternities People from the area broadly coinciding with present-day Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and coastal Montenegro, sharing a com- mon Slavonic language and the Catholic faith, migrated in a steady flux to Italy throughout the Early Modern period.1 The reasons behind the move varied, spanning from often-quoted Ottoman conquests in the Balkans or plague epidemics and famines to the formation of merchant and diplo- matic networks, as well as ecclesiastic or other professional career moves.2 Moreover, a common form of short-term travel to Italy on the part of so- called Schiavoni or Illyrians was the pilgrimage to Loreto or Rome, while the universities of Padua and Bologna, as well as monastery schools, at- tracted Schiavoni / Illyrian students of different social extractions. The first known organized groups described as Schiavoni are mentioned in Italy from the fifteenth century. Through the Early Modern period, Schiavoni / Illyrian confraternities existed in Rome, Venice, throughout the Marche region (Ancona, Ascoli, Recanati, Camerano, Loreto) and in Udine. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

A Jacobite Exile

SIR ANDREW HAY OF RANNES A JACOBITE EXILE By ALISTAIR and HENRIETTA TAYLER LONDON ALEXANDER MACLEHOSE & CO. 1937 A JACOBITE EXILE ERRATUM On jacket and frontispiece, for “Sir Andrew Hay”, read “Andrew Hay” FOREWORD THE material from which the following story is drawn consists principally of the correspondence of Andrew Hay of Rannes down to the year 1763. This is the property of Charles Leith-Hay of Leith Hall, Aberdeenshire, who kindly gave permission for its publication. His Majesty has also graciously allowed certain extracts from the Stuart papers at Windsor to be included. All letters subsequent to 1763, with the exception of one (on page 204) from the Duff House papers, are in the possession of the Editors. They have to thank the Publisher (Heinemann & Co.) for allowing them to reprint passages from their book Lord Fife and his Factor. CONTENTS PART I ......................................................................... 6 1713-1752 ................................................................ 6 PART II ...................................................................... 29 1752-1763 ............................................................. 29 I THE EXILE IN HOLLAND AND FRANCE 29 II THE EXILE IN BELGIUM AND FRANCE 62 III THE EXILE YEARNS FOR HOME ........... 93 IV THE EXILE URGED TO RETURN .......... 135 PART III ................................................................... 156 1763-1789 ............................................................ 156 I THE EXILE LANDS IN ENGLAND ........... 156 APPENDIX I ............................................................ -

The Life of Philip Thomas Howard, OP, Cardinal of Norfolk

lllifa Ex Lrauis 3liiralw* (furnlu* (JlnrWrrp THE LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CARDINAL OF NORFOLK. [The Copyright is reserved.] HMif -ft/ tutorvmjuiei. ifway ROMA Pa && Urtts.etOrl,,* awarzK ^n/^^-hi fofmmatafttrpureisJPTUS oJeffe Chori quo lufas mane<tt Ifouigionis THE LIFE OP PHILIP THOMAS HOWAKD, O.P. CARDINAL OF NORFOLK, GRAND ALMONER TO CATHERINE OF BRAGANZA QUEEN-CONSORT OF KING CHARLES II., AND RESTORER OF THE ENGLISH PROVINCE OF FRIAR-PREACHERS OR DOMINICANS. COMPILED FROM ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS. WITH A SKETCH OF THE EISE, MISSIONS, AND INFLUENCE OF THE DOMINICAN OEDEE, AND OF ITS EARLY HISTORY IN ENGLAND, BY FE. C. F, EAYMUND PALMEE, O.P. LONDON: THOMAS KICHAKDSON AND SON; DUBLIN ; AND DERBY. MDCCCLXVII. TO HENRY, DUKE OF NORFOLK, THIS LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CAEDINAL OF NOEFOLK, is AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED IN MEMORY OF THE FAITH AND VIRTUES OF HIS FATHEE, Dominican Priory, Woodchester, Gloucestershire. PREFACE. The following Life has been compiled mainly from original records and documents still preserved in the Archives of the English Province of Friar-Preachers. The work has at least this recommendation, that the matter is entirely new, as the MSS. from which it is taken have hitherto lain in complete obscurity. It is hoped that it will form an interesting addition to the Ecclesiastical History of Eng land. In the acknowledging of great assist ance from several friends, especial thanks are due to Philip H. Howard, Esq., of Corby Castle, who kindly supplied or directed atten tion to much valuable matter, and contributed a short but graphic sketch of the Life of the Cardinal of Norfolk taken by his father the late Henry Howard, Esq., from a MS. -

The Augustinian Vol VII

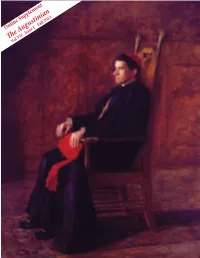

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

Pluscarden Benedictines No

Pluscarden Benedictines No. 186 News and Notes for our Friends Pentecost 2019 Contents Fr Abbot’s Letter 2 From the Annals 4 News from St Mary’s 10 Holy Week Experience 13 Bishop George Hay 14 A Classic Revisited 19 Books Received 22 Tempus per Annum CD Review 31 Why I am a Catholic – G.K. Chesterton 32 Cover: The Paschal Fire 1 FR ABBOT’S LETTER Dear Friends, During Eastertide in the readings at Mass we listen to the Acts of the Apostles, retracing the steps of the Apostles and the first generation of Christians as they go out into the world bearing the Gospel of Jesus. A theme that emerges constantly in this story is “boldness”. What makes the apostles, after they were overcome by fear during the Lord’s trial and death, so bold now? Obviously, it is that they have seen Jesus risen from the dead. So, for them, against any fear of death they have the certainty that death is not the last word and Jesus will fulfil his promise to give eternal life to all who believe in him. But there is more to the apostles’ boldness than the overcoming of fear. In the face of death and suffering, which they must still experience, they are more than defiant and their boldness has no trace of contempt for those at whose hands they suffer. Their confidence is serene and loving. To understand this result of their faith in the Resurrection, we might look at what Jesus says to Nicodemus in John 3:15-16. -

Archive Catalogue Content

Archive catalogue content - http://archive.catholic-heritage.net/ Institution Archon code Number of catalogue entries page England, London Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales GB 3280 1107 4 Society of Jesus, British Province GB 1093 293 17 Westminster Diocesan Archives GB 0122 9156 3 Italy, Rome Pontifical Scots College GB 1568 112 18 Scotland, Edinburgh Scottish Catholic Archives GB 0240 19341 7 Spain, Salamanca Royal Scots College GB 3128 421 5 Spain, Valladolid Royal English College GB 2320 4948 6 Total 35378 1 | P a g e 02 M a y 2 0 1 2 Archive catalogue content - http://archive.catholic-heritage.net/ Repository Reference(s) Collections included Date(s) Number Cataloguing Last update of entries status Westminster Diocesan Archives AAW AAW/DOW Diocese of Westminster [17th cent-present] Ongoing 2012.01.01 2 | P a g e 02 M a y 2 0 1 2 Archive catalogue content - http://archive.catholic-heritage.net/ Repository Reference(s) Collections included Date(s) Number Cataloguing Last update of entries status Catholic Bishops’ Conference of CBCEW England and Wales CBCEW/CONFP Conference Plenary meetings [19th cent-20th cent] Ongoing 2012.01.01 CBCEW/CONFS Conference Secretariat [19th cent-20th cent] Ongoing 2012.01.01 CBCEW/CaTEW Catholic Trust for England and Wales [19th cent-20th cent] Ongoing 2012.01.01 CBCEW/STAN Standing Committee [19th cent-20th cent] Ongoing 2012.01.01 3 | P a g e 02 M a y 2 0 1 2 Archive catalogue content - http://archive.catholic-heritage.net/ Repository Reference(s) Collections included Date(s) Number Cataloguing -

The History of the Augustinians As a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1965 The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province Joseph Anthony Linehan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Linehan, Joseph Anthony, "The History of the Augustinians as a Teaching Order in the Midwestern Province" (1965). Dissertations. 776. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/776 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 1965 Joseph Anthony Linehan THF' RISTORI OF Tl[F, AUOUSTINIANS AS A Tt'ACHINO ormm IN THE JlIDWlmERN PlOVIlCR A nt. ..ertat.1on Submi toted to the Facul\7 ot the Gra.da1&te School of ~1a Un! wnd.ty in Partial PUlt1l.l.aent ot the Requirements tor the Degree of Docrtor of Fdnoation I would 11ke to thank the Reverend Daniel lI&rt1gan, O.S.A., who christened. th1s etud7. Reverend lf10bael Ibgan, D.S.A., who put it on ita feet, Dr. Jobn V.roz!'l1a.k, who taught it to walk. and Dr. Paul t1nieJ7, wm guided 1t. ThanlaI to st. Joseph Oupert1no who nlWer fails. How can one adequate~ thank his parente tor their sacrlf'loee, their 10... and their guidanoe. Is thank JOt! suttlc1ent tor a nil! who encourages when night school beoomea intolerable' 1bw do ,ou repay two 11 ttle glrls liM mat not 'bo'ther daddy in h1s "Portent- 1"OGIIl? Tou CIDIOt appreoiate tbe exoeUent teachers who .Mope )'Our future until you a~ an adult. -

January - March 2021

January - March 2021 JANUARY - MARCH 2010 Journal of Franciscan Culture Issued by the Franciscan Friars (OFM Malta) 135 Editorial EDITORIAL THE DEMOCRATIC DIMENSION OF AUTHORITY The Catholic Church is considered to be a kind of theocratic monarchy by the mass media. There is no such thing as a democratically elected government in the Church. On the universal level the Church is governed by the Pope. As a political figure the Pope is the head of state of the Vatican City, which functions as a mini-state with all the complexities of government Quarterly journal of and diplomatic bureaucracy, with the Secretariat of State, Franciscan culture published since April 1986. Congregations, Offices and the esteemed service of its diplomatic corps made up of Apostolic Nuncios in so many countries. On Layout: the local level the Church is governed by the Bishop and all the John Abela ofm Computer Setting: government structures of a Diocese. There is, of course, place for Raymond Camilleri ofm consultation and elections within the ecclesiastical structure, but the ultimate decisions rest with the men at the top. The same can Available at: be said of religious Orders, having their international, national http://www.i-tau.com and local organs of government. The Franciscan Order is also structured in this way, with the minister general, the ministers All original material is Copyright © TAU Franciscan provincial, custodes and local guardians and superiors. Communications 2021 Indeed, Saint Francis envisaged a kind of fraternity based on mutual co-responsibility. He did not accept the title of abbot or prior for the superiors of the Order, but wanted them to be “ministers and servants” of the brotherhood.