Arthur D. Beard III Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alshire Records Discography

Alshire Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Alshire International Records Discography Alshire was located at P.O. Box 7107, Burbank, CA 91505 (Street address: 2818 West Pico Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90006). Founded by Al Sherman in 1964, who bought the Somerset catalog from Dick L. Miller. Arlen, Grit and Oscar were subsidiaries. Alshire was a grocery store rack budget label whose main staple was the “101 Strings Orchestra,” which was several different orchestras over the years, more of a franchise than a single organization. Alshire M/S 3000 Series: M/S 3001 –“Oh Yeah!” A Polka Party – Coal Diggers with Happy Tony [1967] Reissue of Somerset SF 30100. Oh Yeah!/Don't Throw Beer Bottles At The Band/Yak To Na Wojence (Fortunes Of War)/Piwo Polka (Beer Polka)/Wanda And Stash/Moja Marish (My Mary)/Zosia (Sophie)/Ragman Polka/From Ungvara/Disc Jocky Polka/Nie Puki Jashiu (Don't Knock Johnny) Alshire M/ST 5000 Series M/ST 5000 - Stephen Foster - 101 Strings [1964] Beautiful Dreamer/Camptown Races/Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair/Oh Susanna/Old Folks At Home/Steamboat 'Round The Bend/My Old Kentucky Home/Ring Ring De Bango/Come, Where My Love Lies Dreaming/Tribute To Foster Medley/Old Black Joe M/ST 5001 - Victor Herbert - 101 Strings [1964] Ah! Sweet Mystery Of Life/Kiss Me Again/March Of The Toys, Toyland/Indian Summer/Gypsy Love Song/Red Mill Overture/Because You're You/Moonbeams/Every Day Is Ladies' Day To Me/In Old New York/Isle Of Our Dreams M/S 5002 - John Philip Sousa, George M. -

Disability Awareness

DISABILITY AWARENESS MUSIC & WORSHIP RESOURCES Sunday, October 18, 2009 Marcus D. Smith, Guest Lectionary Liturgist Minister of Music, Ark Church, Baltimore, MD and W. Patrick Alston, Sr., Lectionary Team Liturgist Worship Planning Notes The Church has failed to adequately accommodate and include its members who have disabilities. Beyond singing ministries offered by a few churches and wheelchair ramps in a few churches, little evidence can be found of our purposeful attempts to include all in the worship and activities of the Church. This must change! Technology now makes so much possible if we have willing hearts and minds. Many congregations now have within their ranks numerous persons who have Down syndrome or autism, who are blind or deaf, who use wheelchairs, or have other disabilities. Most of these persons are more than able to participate in the life of the Church if we assist them. Many of your church members have disabilities, as statistically one in five individuals has a disability. Present to the congregation a survey that includes questions about each member’s abilities, needs, and desires to be part of your church’s activities. Many people have disabilities that are not immediately apparent, such as vision difficulties, physical challenges, or mental illness, so it is important to ask everyone if his or her needs are being met. Do a thorough assessment of your programs and policies to determine if you have faithfully done all that you can do to include persons with disabilities and those who are differently-abled in the life of the church. This assessment should take no more than two months to complete and should include a plan for implementation, a budget, and timelines for each act that is to be implemented. -

Book Review: the Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.Com

Book Review: The Fan Who Knew Too Much - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB1000142405270230390150457... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now BOOKSHELF Updated June 29, 2012, 5:30 p.m. ET The Queen of Soul's Long Reign By EDDIE DEAN One of the more indelible moments from the Obama inauguration was the spectacle of Aretha Franklin singing her gospel rendition of "My Country, 'Tis of Thee," as poignant to watch as it was painful to hear. Bundled in an overcoat, gloves and a Sunday-go-to-meeting hat with a jumbo ribbon bow, she struggled in the raw winter cold to kindle her time-ravaged voice, once one of the wonders of the modern world. The performance was less about hitting the high notes than striking a chord with the flock: Here was America's Church Lady come to bless her children. It's a role that the 70-year-old Ms. Franklin plays quite well at ceremonies of state and funerals and whenever the occasion demands. But she also enjoys a Saturday night out as the reigning Queen of Soul, as when she regaled a stadium crowd at WrestleMania 23 in 2007 in her hometown of Detroit. Such cameos run the risk of making her a kind of caricature—someone who has overstayed her welcome on the pop-culture stage and become, like Orson Welles in his later years, the honorary emblem of antiquated if revered Americana. -

Oh Happy Day

PART 4: Activities & Resources: Music in Honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Meet the Sounds of Blackness, 2015 WITNESS Guest Artists One: Meet the Artists . 81 Two: Listen and Respond to Music by Sounds of Blackness . 82 Student Reading: Meet the Sounds of Blackness . 85 Graphic Organizer: A Bio Wheel for Sounds of Blackness . 87 Musical Roots of Spirituals, Gospel and Rhythm & Blues (R&B) One: Listen and “Respond to Ubuntu” . 89 Two: African Roots of American Music . 93 Student Reading: “The Roots of African American Music” . 96 Reading for Teachers and Older Students: “Characteristics of West African Music” . 98 Poem: “Origins” by Toyomi Igus from I See the Rhythm . 99 78 Three: Spirituals . 100 Reading for Teachers & Older Students: “About Spirituals” . 102 Listening Log for Oh, Freedom . 104 Sheet Music: Oh, Freedom . 105 Four: Becoming Aware of Gospel Music . 106 Student Reading: Gospel Music in the U .S .A . 108 Student Handout: Listening Map for March Song Medley . 109 Five: Gospel Music . 110 Student Handout: Lyrics for Oh Happy Day . 109 Six: Rhythm & Blues . 114 Student Reading: Rhythm & Blues . 117 WITNESS 79 Sound of Blackness: Guest Artists for the 2015 WITNESS Young People’s Concert Introduction The guest artists for the 2015 WITNESS the theme and focus of the 2015 WITNESS Young People’s Concert is the Minnesota- Young People’s Concert, and hearing the music based ensemble, Sounds of Blackness. The will ignite their interest in hearing the live activities in this lesson will introduce students performance. to the ensemble and their music. Students will If this is your first WITNESS lesson, provide read a biography, view a PowerPoint, and listen folders for each student to collect handouts, to a piece from the WITNESS Companion materials, and their own work related to the CD. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

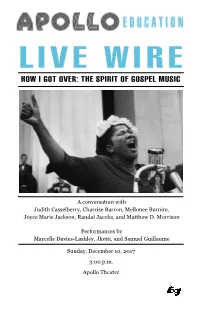

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

James M. Black and Friends, Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music

James M. Black and Friends Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music by Milton W. Loyer, 2004 Three distinctives separate Wesleyan Methodism from other religious denominations and movements: (1) emphasis on the heart-warming salvation experience and the call to personal piety, (2) concern for social justice and persons of all stations of life, and (3) using hymns to bring the gospel message to people in a meaningful way. All three of these distinctives came together around 1900 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in the person of James M. Black and the congregation at the Pine Street Methodist Episcopal Church. Because there were other local persons and companies associated with bands, instruments and secular music during this time, the period is often referred to as “Williamsport’s Golden Age of Music.” While papers have been written on other aspects of this musical phenomenon, its evangelical religious component has generally been ignored. We seek to correct that oversight. James Milton Black (1856-1938) is widely known as the author of the words and music to the popular gospel song When the Roll is Called Up Yonder . He was, however, a very private person whose failure to leave much documentation about his work has frustrated musicologists for decades. No photograph of him suitable for large-size reproduction in gospel song histories, for example, is known to exist. Every year the United Methodist Archives at Lycoming College expects to get at least one inquiry that begins, “I just discovered that James M. Black was a Methodist layperson from Williamsport, could you please tell me…” We now attempt to bring together all that is known about the elusive James M. -

The Lubbock Texas Quartet and Odis 'Pop' Echols

24 TheThe LubbockLubbock TexasTexas QuartetQuartet andand OdisOdis “Pop”“Pop” Echols:Echols: Promoting Southern Gospel Music on the High Plains of Texas Curtis L. Peoples The Original Stamps Quartet: Palmer Wheeler, Roy Wheeler, Dwight Brock, Odis Echols, and Frank Stamps. Courtesy of Crossroads of Music Archive, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, Echols Family Collection, A Diverse forms of religious music have always been important to the cultural fabric of the Lone Star State. In both black and white communities, gospel music has been an influential genre in which many musicians received some of their earliest musical training. Likewise, many Texans have played a significant role in shaping the national and international gospel music scenes. Despite the importance of gospel music in Texas, little scholarly attention has been devoted to this popular genre. Through the years, gospel has seen stylistic changes and the 25 development of subgenres. This article focuses on the subgenre of Southern gospel music, also commonly known as quartet music. While it is primarily an Anglo style of music, Southern gospel influences are multicultural. Southern gospel is performed over a wide geographic area, especially in the American South and Southwest, although this study looks specifically at developments in Northwest Texas during the early twentieth century. Organized efforts to promote Southern gospel began in 1910 when James D. Vaughn established a traveling quartet to help sell his songbooks.1 The songbooks were written with shape-notes, part of a religious singing method based on symbols rather than traditional musical notation. In addition to performing, gospel quartets often taught music in peripatetic singing schools using the shape-note method. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in Twentieth-Century African American Literature

“UP ABOVE MY HEAD”: GOSPEL MUSIC AND THE SONIC FICTIONS OF BLACK WOMANHOOD IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE Kimberly Gibbs Burnett A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature in the Graduate School. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Danielle Christmas Florence Dore GerShun Avilez Glenn Hinson Candace Epps-Robertson ©2020 Kimberly Gibbs Burnett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kimberly Burnett: “Up Above My Head”: Gospel Music and the Sonic Fictions of Black Womanhood in TWentieth-Century African American Literature (Under the direction of Dr. Danielle Christmas) DraWing from DuBois’s Souls of Black Folk (1903), which highlighted the Negro spirituals as a means of documenting the existence of a soul for an African American community culturally reduced to their bodily functions, gospel music figures as a reminder of the narrative of black women’s struggle for humanity and of the literary markers of a black feminist ontology. As the attention to gospel music in texts about black women demonstrates, the material conditions of poverty and oppression did not exclude the existence of their spiritual value—of their claim to humanity that was not based on conduct or social decorum. At root, this project seeks to further the scholarship in sound and black feminist studies— applying concepts, such as saturation, break, and technology to the interpretation of black womanhood in the vernacular and cultural recordings of gospel in literature. Further, this dissertation seeks to offer neW historiography of black female development in tWentieth century literature—one which is shaped by a sounding culture that took place in choir stands, on radios in cramped kitchens, and on stages all across the nation. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

The Production of Gospel Music: an Ethnographic Study of Studio-Recorded Music in Bellville, Cape Town

The production of gospel music: An ethnographic study of studio-recorded music in Bellville, Cape Town A mini thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Robin L. Thompson Department of Anthropology and Sociology University of the Western Cape November 2015 Supervisor: Professor Heike Becker Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................ ......................................................... i Declaration ................................................................ ................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1: Introduction ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 The prevalence of Pentecostalism and music in Christian households, churches and media in Cape Town .............................................................................................................................................................4 1.2 Rethinking the idea of genre through ‘Pentecospel’ music ....................................................................8 1.3 Going forth ............................................................................................................................................10 1.4 Chapter Outline