Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows John Constable Contents Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable

return to list of Publications and Lectures Changes in the Appearance of Paintings by John Constable Charles S. Rhyne Professor, Art History Reed College published in Appearance, Opinion, Change: Evaluating the Look of Paintings Papers given at a conference held jointly by the United Kingdom institute for Conservation and the Association of Art Historians, June 1990. London: United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 1990, p.72-84. Abstract This paper reviews the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by one artist, John Constable. The intention is not simply to describe changes in the work of Constable but to suggest a framework for the study of changes in the work of any artist and to facilitate discussion among conservators, conservation scientists, curators, and art historians. The paper considers, first, examples of physical changes in the paintings themselves; second, changes in the physical conditions under which Constable's paintings have been viewed. These same examples serve to consider changes in the cultural and psychological contexts in which Constable's paintings have been understood and interpreted Introduction The purpose of this paper is to review the remarkable diversity of changes in the appearance of paintings by a single artist to see what questions these raise and how the varying answers we give to them might affect our work as conservators, scientists, curators, and historians. [1] My intention is not simply to describe changes in the appearance of paintings by John Constable but to suggest a framework that I hope will be helpful in considering changes in the paintings of any artist and to facilitate comparisons among artists. -

Centenary Celebration Report

Celebrating 100 years CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2018 Front cover photograph: Choristers representing CSA’s three founding member schools, with lay clerks and girl choristers from Salisbury Cathedral, join together to celebrate a Centenary Evensong in St Paul’s Cathedral 2018 CONFERENCE REPORT ........................................................................ s the Choir Schools’ Association (CSA) prepares to enter its second century, A it would be difficult to imagine a better location for its annual conference than New Change, London EC4, where most of this year’s sessions took place in the light-filled 21st-century surroundings of the K&L Gates law firm’s new conference rooms, with their stunning views of St Paul’s Cathedral and its Choir School over the road. One hundred years ago, the then headmaster of St Paul’s Cathedral Choir School, Reverend R H Couchman, joined his colleagues from King’s College School, Cambridge and Westminster Abbey Choir School to consider the sustainability of choir schools in the light of rigorous inspections of independent schools and regulations governing the employment of children being introduced under the terms of the Fisher Education Act. Although cathedral choristers were quickly exempted from the new employment legislation, the meeting led to the formation of the CSA, and Couchman was its honorary secretary until his retirement in 1937. He, more than anyone, ensured that it developed strongly, wrote Alan Mould, former headmaster of St John’s College School, Cambridge, in The English -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral & John Fisher

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral & John Fisher On the 10th February 1829, John Constable finally realised his dream of becoming an Academician and later in the month he exhibited what is for many, his most ‘Sublime’ painting, Hadleigh Castle, that is the one that most eloquently expressed the emotional turmoil attendant to his wife’s death just a few months earlier. In this painting, the three aspects of ‘Chiaroscuro’, as a natural phenomenon, a pictorial device and as a metaphor for the range of human emotions, were so instinctively combined by Constable, that for him, to an unprecedented degree, the act of painting became an instrument of self- confession. Indeed, Constable may have been the first painter, to apply the term Chiaroscuro, hitherto used in relation to art, to the appearance of Nature, highlighted by this remark to Fisher: ‘I live by shadows; to me shadows are realities.’ Hadleigh Castle, oil on canvas, 48x64 inches, Yale Centre for British Art Constable visited Hadleigh in 1814 at which time he made several sketches of the coastline of the Thames estuary. The picture was painted at Hampstead and before bringing it to the exhibition, he confessed his anxieties to Leslie, his friend and biographer, as he was still smarting after his election and Sir Thomas Lawrence’s insensitive remarks on his admission to the Academy as an Academician, where he only defeated Francis Danby by one vote. When Constable made his official call upon Lawrence, the President of the Academy, Lawrence, ‘Did not conceal from his visitor that he considered him peculiarly fortunate in being chosen as an Academician at a time when there were historical painters of great merit on the list of candidates.’ Coming at this time, the event was, as he said, ‘devoid of all satisfaction’. -

William Kay Phd Thesis

LIVING STONES: THE PRACTICE OF REMEMBRANCE AT LINCOLN CATHEDRAL, (1092-1235) William Kay A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2013 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/4463 This item is protected by original copyright LIVING STONES THE PRACTICE OF REMEMBRANCE AT LINCOLN CATHEDRAL (1092-1235) William Kay This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 1 August 2013 I, William Kay, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in September, 2005; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2013. Date ………. signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date ………. signature of supervisor ……………… In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL Timeline and Significant Events. Post Conquest

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL Timeline and significant events. Post Conquest 1075-92 At the Council of London it was decreed that bishoprics should not be continued in small towns or villages where clergy could be exposed to violence from local (English) residents. The King urged the Bishops to move to towns where defensive structures could be built with a garrison to protect the Norman settlers and the clergy. The dioceses of Sherborne and Ramsbury were merged at Old Sarum in Wiltshire, a castle built within a walled precinct and a new abbey next to it, consecrated 1092. Bishop Osmund supervised the building of this large Norman cathedral. 1200-20 The resident canons were unhappy with the exposed site at Old Sarum, and there were conflicts of interest between the castle and the abbey which lead Bishop Herbert Poore to seek a Papal Bull to relocate the Cathedral 2 miles away on land (80 acres) owned by his brother Richard Poore, who was planning a new town by the River Avon, large enough for the proposed cathedral complex. This was the beginning of Salisbury. 1220-58 Richard Poore succeeded his brother as Bishop in 2017 and he laid out the foundations for the new cathedral starting at the east end chapels, then the presbytery and eastern transepts, followed by the crossing, choir and western transepts c.1240. The master mason was Nicholas of Ely, working under the direction of canon Elias of Dereham. Their combined efforts produced one of the most stately cathedrals in England, praised for its consistency of style (mostly Early English) and restrained use of decorative ornament . -

Friends of Bruton Tour of Historic Cathedrals and Churches Of

Friends of Bruton Tour of Historic Cathedrals and Churches of England May 16-25, 2014 Join Father John Maxwell Kerr, Episcopal Chaplain to the faculty, staff and students at The College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia for a very special tour and pilgrimage to many of the most historic cathedrals and churches of England. Sponsored by Friends of Bruton: Our Worldwide Congregation Bruton Parish Church Williamsburg, Virginia The May 2014 tour of historic cathedrals of England sponsored by Friends of Bruton is open to everyone, you don't even have to be an Episcopalian! A message from Father Kerr I rather hope you will not think of our journey together as mere ‘religious tourism.’ There would be little point in having a priest and scholar accompanying anything other than a pilgrimage, for that is how I do see Bruton’s visit to Britain next May. Look closely at our itinerary: we plan to attend Divine Offices of the Church of England at cathedrals, churches and other holy places we shall visit (alas, an exception must be made for Stonehenge!) My own knowledge of people and places came not as a tourist but as a priest of thirty-five years’ standing in the Church of England. I loved to worship in these ancestral homes of our Anglican faith. Beauty, ancient and modern, of architecture; beauty, ancient and modern, of the great musical tradition we inherit (and to which we Episcopalians contribute to this day); the beauty of holiness - prayer in words ancient and modern, sung and spoken through so many lifetimes - the long history of the Church of England’s inheritance is ours too. -

Sixth Sunday of Easter

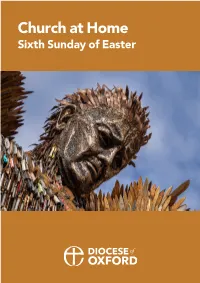

Church at Home Sixth Sunday of Easter 1 Before the Service Love one another Welcome to Church at Home for the sixth Sunday of Easter. In our service we will be exploring the theme of providing love and hospitality, especially to those who are viewed by mainstream society as not deserving God’s love. We are delighted to have as our president today the Right Revd Olivia Graham, Bishop of Reading, and that our reflection is given by the Venerable Canon Stephen Pullin, the Archdeacon of Berkshire. Huge thanks to everyone from across the diocese who has contributed ideas, prayers and action to this week’s Church at Home. You have made this service possible. In ancient times, on or Just before this (Rogation) Sunday, days of prayer and fasting were observed in Western Christianity. Ironically, one of the ancient customs also marked at this time is ‘beating the bounds’, during which parishes would go on a procession to protect public right of way from agricultural or other expansion. However, as someone said, if the Christian faith is instead compared to a dance, then our mission is for a constant expansion of the dancefloor, to include those on the margins. Our gospel reading calls us to a fruitful love of the other like Jesus does us - a love that’s in it for the long haul. The Jesus of the gospels lived at the edges of polite society. He was out in the wild untamed places of the community, as if in perpetual search for the ‘other’, the one who didn’t ‘belong.’ The Jewish leaders of his day, who considered his self-sacrificial vocation absurd, could not get their heads around such love. -

Marriage, Sin and the Community in the Register of John Chandler

Marriage, Sin and the Community in the Register of John Chandler, Dean of Salisbury 1404-17 by Byron J. Hartsfield A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: David R. Carr, Ph.D. Gregory B. Milton, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 16, 2007 Keywords: medieval England, social history, church courts, disputed marriage, self- divorce, domestic violence © Copyright 2007, Byron J. Hartsfield To Mom and Carine. Table of Contents List of Figures ii Abstract iii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Historiography 18 Legal Historians, Canon-Law Courts, and Social Control 18 Social Historians and the History of the Medieval English Family 32 Chapter Three: Adultery 55 Compurgation 64 Sentences of Fustigation 72 Fines Paid in Lieu of Fustigation 79 Abjuration 85 Chapter Four: Fornication 91 Compurgation 95 Sentences of Fustigation 100 Fines Paid in Lieu of Fustigation 104 Abjuration 106 Chapter Five: Disputed Marriages 113 Chapter Six: Abandonment and “Self-Divorce” 137 Chapter Seven: Marital Abuse 158 Chapter Eight: Conclusion 170 List of References 175 Appendices 179 Appendix A: Sins Reported in Dean Chandler’s Register 180 Appendix B: Adultery in Dean Chandler’s Register 182 Appendix C: Fornication in Dean Chandler’s Register 184 i List of Figures Figure 1. Adultery and Compurgation in Dean Chandler’s Register 66 Figure 2. Fines Associated with Abjuration of Adultery 88 Figure 3. Fornication and Compurgation in Dean Chandler’s Register 97 Figure 4. Penalties Associated with Abjuration of Fornication 109 ii Marriage, Sin and the Community in the Register of John Chandler, Dean of Salisbury 1404-17 Byron J. -

ORDER EXPLANATORY DOCUMENT Annex B Full Li

GS 2128X THE ARCHBISHOPS’ COUNCIL DRAFT LEGISLATIVE REFORM (PATRONAGE OF BENEFICES) ORDER EXPLANATORY DOCUMENT Annex B Full list of respondents: Agnes Cape, parishioner Andrew Bell, Church warden and Synod Member, Oxford Andrew Robinson, Diocesan Secretary, Winchester Andy Sharp, Lay Co-chair of the PCC of St Stephen with St Julian, St Albans Angus Deas, Pastoral and Closed Churches Officer, Diocese of York Anne Stunt, Secretary to the Board of Patronage, Portsmouth Diocese Anthony Jennings on behalf of the English Clergy Association, the Patrons Group and Save Our Parsonages Archdeacon of Berkshire, Olivia Graham Archdeacon of Bodmin, Audrey Elkington Archdeacon of Lewisham & Greenwich, Alastair Cutting Archdeacon of Norfolk, Steven Betts Archdeacon of Southwark, Jane Steen Archdeacon of Sudbury, David Jenkins Archdeacon of West Cumberland, Richard Pratt on behalf of all Carlisle diocese archdeacons Archdeacons of Ludlow and Hereford Archdeacons of Winchester and Bournemouth Ashley Wilson, Patronage Secretary, St Chad’s College Bishop of Leicester and the Bishop’s Leadership Team Bishop of Selby, John Thomson Bishop of Whitby, Paul Ferguson Bishop of Willesden, Pete Broadbent Caroline Mockford, Registrar of the Province & Diocese of York, for and on behalf of Lupton Fawcett LLP Chapter of Durham Cathedral Chapter of York Cathedral Chris Gill, Lay Chair of Deanery Synod, Lichfield Christopher Whitmey, PCC Member, Hereford City of London Corporation Clare Spooner, Diocesan Pastoral Officer, Lichfield Clive Scowen, Lay Synod Member, London