Exploring Contemporary United Kingdom Trade Unions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DECEMBER 2015 Page 1 Editorial: Handcarts in Convoy

NEWSLETTER Editorial – 2 General practice on the brink – 4 Junior doctors: the wider view– 5 Barts merger nightmare – 7 Manslaughter and beyond – 8 AGM and Conference 2015 – 11-21 AGM: Reports – 12 AGM: General practice – 14 AGM: New politics – 16 AGM: Devo-Manc – 17 Git et qui nonAGM: et ommollesFYFV – 18 corempo AGM: Devolution – 19 AGM: Paul Noone Memorial Lecture – 20 Mental health: What lies ahead – 22 Executive Committee 2015-16 – 24 Page 1 DECEMBER 2015 Page 1 Editorial: Handcarts in convoy Despite 70 years of continual old- and (as someone else pointed out testament-worthy predictions of when they highlighted the high-risk terminal melt-down, the NHS government strategy of targeting the arrives, join our happy team” – the won’t do that, just as it hasn’t juniors) very definitely neither on usual depressing PR-speak. since 1948. We’d do well not to the golf course nor seeing private Interestingly, many of the trusts were proclaim its demise – a ritual patients. I spoke to a couple of – though you’d never know it looking pronouncement every winter. foundation year doctors. They told at the pictures of happy-clappy But its foundations continue me of their concerns for patient healthcare professionals – in special to be eroded in ways that safety, their insecurity about their measures or otherwise engaged only intermittently make the long-term futures, and the instability with the CQC, so were obeying the headlines. Without seeking out of their organisations. By the time management-consultant mantra of trouble – or even information, for this is in print, they will either have smiling especially broadly when you’re that matter – in the past couple become the 2015 equivalents of in your death throes, and hoping of weeks several of the demons the miners under Mrs Thatcher, or that some people might not notice gave me a good nip. -

Bio Testimony Combined

TABLE OF CONTENTS Thursday, May 14, 2020 William “Bill” Johnson Biography ................................................................................... 2 William “Bill” Johnson Testimony ................................................................................ 3-7 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment .......................................................................... 8-157 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 158-169 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 170-178 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ....................................................................... 179-193 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ....................................................................... 194-201 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ...................................................................... 202-203 William “Bill” Johnson Attachment ............................................................................. 204 Mark Napier Biography ................................................................................................ 205 Mark Napier Testimony ......................................................................................... 206-210 Mark Napier Attachment ...................................................................................... 211-235 Michael Harrison Biography ......................................................................................... 236 Michael -

Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 586 HE 032 364 AUTHOR Farnham, David, Ed. TITLE Managing Academic Staff in Changing University Systems: International Trends and Comparisons. INSTITUTION Society for Research into Higher Education, Ltd., London (England). ISBN ISBN-0-335-19961-5 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 376p. AVAILABLE FROM Open University Press, 325 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106. Web site: <http://www.openup.co.uk>. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC16 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College Faculty; Cross Cultural Studies; *Educational Administration; *Educational Policy; Foreign Countries; *Higher Education; Human Resources; Legislation; Public Policy; Teacher Salaries; Teaching (Occupation); Universities ABSTRACT This collection of 17 essays focuses on how faculty are employed, rewarded, and managed at universities in developed and developing nations. The essays, which include an introduction, 10 essays discussing European practices, two that focus on Canada and the United States, three which focus on Australia, Japan, and Malaysia, and a concluding chapter are: (1)"Managing Universities and Regulating Academic Labour Markets" (David Farnham); (2) "Belgium: Diverging Professions in Twin Communities" (Jef C. Verhoeven and Ilse Beuselinck); (3) "Finland: Searching for Performance and Flexibility" (Turo Virtanen); (4) "France: A Centrally-Driven Profession" (June Burnham); (5) "Germany: A Dual Academy" (Tassilo Herrschel); (6) "Ireland: A Two-Tier Structure" (Thomas N. Garavan, Patrick Gunnigle, and Michael Morley); (7) "Italy: A Corporation Controlling a System in Collapse" (William Brierley); (8) "The Netherlands: Reshaping the Employment Relationship" (Egbert de Weert); (9) "Spain: Old Elite or New Meritocracy?" (Salavador Parrado-Diez); (10) "Sweden: Professional Diversity in an Egalitarian System" (Berit Askling); (11) "The United Kingdom: End of the Donnish Dominion?" (David Farnham); (12) "Canada: Neo-Conservative Challenges to Faculty and Their Unions" (Donald C. -

Annual Report of the Certification Officer | 2013-2014

Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 www.certoffice.org CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2013-2014 www.certoffice.org © Crown Copyright 2014 First published 2014 ii The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Sir Brendan Barber Chair of ACAS Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service Euston Tower 286 Euston Road London NW1 3JJ I am required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 to submit to you both a report on my activities as the Certification Officer during the previous reporting period. I have pleasure in submitting such a report for the period 1 April 2013 to 31 March 2014. DAVID COCKBURN The Certification Officer 24 June 2014 iii Contents Page Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Lists of Trade Unions and Employers’ Associations 5 Entry in the lists and its significance 5 Unions and employers’ associations formed by an amalgamation 6 Trade unions and employers’ associations not on the lists (scheduled bodies) 6 Removal from the lists and schedules 6 Additions to the lists and schedules 8 The lists and schedules at 31 March 2014 8 Special register bodies 9 Changes of name of listed trade unions and employers’ associations 10 Definition of a trade union 11 Definition of an employers’ association 11 2 Trade Union Independence 13 The statutory provisions 13 Criteria 14 Applications, decisions, reviews and appeals 14 3 Annual Returns, Financial Irregularities -

For Unions the Future

the future for unions Tom Wilson This publication has been produced with the kind support of Russell Jones & Walker Solicitors. © No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing from Unions 21. Registered offi ce Unions 21 Swinton House 324 Gray’s Inn Road London WC1X 8DD Contents Foreword – Debate 4 Biography – Tom Wilson 5 Summary 5 Introduction 6 A 9-point plan for growth 7 Union membership 12 Like recruits like: the importance of occupation 13 Public versus private 16 Equality and gender: the feminisation of the unions 18 Education 20 The changing shape of the union movement 21 Vulnerable workers 22 Students and young workers 24 The unions themselves 25 Size: to merge or not to merge? 30 What makes a successful union? 33 Appendix 34 Debate Unions 21 exists to provide an ‘open space’ for discussion on the future of the trade union movement and help build tomorrow’s unions in the UK. We are mainly resourced by contributions from trade unions and others who work with trade unions that recognise we need to keep the movement evolving in an ever changing world. We encourage discussion on tomorrow’s unions through publications, conferences, seminars and similar activities. The Debate series of publications present opinions upon the challenges trade unions are facing, solutions they may consider and best practice they may adopt. These opinions are not endorsed by Unions 21, but are published by us to encourage the much needed, sensible and realistic debate that is required if the trade union movement is going to prosper. -

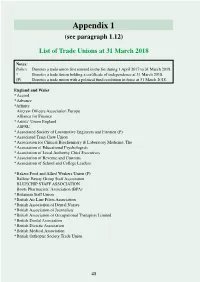

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Taxpayer Funding of Trade Unions 2012-13

Research Note 140 | 10 September 2014 Taxpayer funding of trade unions 2012-13 Last year Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude announced plans to reduce the amount of facility time taken by Civil Servants on Whitehall. This will cut the subsidy that unions receive at taxpayers’ expense. There is still be a substantial subsidy however, and the reforms do not yet apply to the broader public sector. As of April 2013, the Cabinet Office has been publishing facility time figures for central government departments online, an encouraging step towards transparency. Earlier TaxPayers’ Alliance research in this area revealed the extent of trade union subsidies across the public sector for the first time. This research updates that evidence of the huge amounts of taxpayers’ money given to trade unions through direct funding or paid staff time from public sector bodies. It contains information about the number of public sector bodies automatically deducting trade union subscriptions in the payroll process, often without charging the unions for that additional administrative support. The key findings of this research are: . Trade unions received a subsidy of at least £108 million at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. This is made up of an estimated £85 million in paid staff time, plus £23 million in direct payments. At least 2,841 full-time equivalent (FTE) public sector staff worked on trade union duties at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. The number of full-time equivalent staff provided to trade unions is 2.5 times as large as the workforce of HM Treasury.1 . 344 public sector organisations (out of the 1,074 surveyed) either did not fully record facility time or did not record it at all in 2012-13. -

RESEARCH REPORT 070 HSE Health & Safety Executive

HSE Health & Safety Executive Analysis of compensation claims related to health and safety issues Prepared by System Concepts for the Health and Safety Executive 2003 RESEARCH REPORT 070 HSE Health & Safety Executive Analysis of compensation claims related to health and safety issues Laura Peebles, Tanya Heasman and Vivienne Robertson System Concepts 2 Savoy Court London WC2R 0EZ United Kingdom This report details the findings of a research project to collect and analyse health and safety (accident and injury-related) compensation claims conducted via trade unions and law firms. Specific objectives of the study were to answer the following questions: What are the main types of claim? What are the main injuries sustained? What are the industry sectors which attract the highest proportion of claims? What are the work activities which give rise to the most claims? What breaches of the Regulations are most likely to attract claims? How long does it take for claims to be settled? What are the average costs of claims? This report and the work it describes were funded by the HSE. Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect HSE policy. HSE BOOKS © Crown copyright 2003 First published 2003 ISBN 0 7176 2612 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to: Licensing Division, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ or by e-mail to [email protected] ii CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY VII 1. -

NMC); a Public Consultation on Post Registration Standards

Unite the Union (in Health) Professional Team 128 Theobald’s Road, Holborn, London, WC1X 8TN T: 020 7611 2500 | E: [email protected] Unite the Union Response to: The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC); a public consultation on post registration standards. This response is submitted by Unite in Health. Unite is one of the UK’s largest trade union with 1.5 million members across the private and public sectors. The union’s members work in a range of industries including manufacturing, financial services, print, media, construction, transport, local government, education, health and not for profit sectors. Unite represents in excess of 100,000 health sector workers. This includes eight professional associations - British Veterinary Union (BVU), College of Health Care Chaplains (CHCC), Community Practitioners and Health Visitors’ Association (CPHVA), Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists (GHP), Hospital Physicists Association (HPA), Doctors in Unite (formerly MPU), Mental Health Nurses Association (MHNA), Society of Sexual Health Advisors (SSHA). Unite also represents members in occupations such as nursing, allied health professions, healthcare science, applied psychology, counselling and psychotherapy, dental professions, audiology, optometry, building trades, estates, craft and maintenance, administration, ICT, support services and ambulance services. Len McCluskey www.unitetheunion.org General Secretary 2 Executive Summary Introduction Unite CPHVA welcomes the opportunity to respond to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) consultation; a public consultation on post registration standards. Unite CPHVA has been involved in this work from its inception and has had representatives on the Programme Board and Standards Development Group. This has been a positive experience and has been welcomed as Unite CPHVA has been calling for a review of the out dated Specialist Community Public Health Nursing (SCPHN) standards for over ten years. -

Leading the Dragon Lessons for Wales from the Basque Mondragon Co- Operative

Leading the dragon Lessons for Wales from the Basque Mondragon co- operative Edited by John Osmond Supported by The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well being of Wales. The IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals, including the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, the Waterloo Foundation and PricewaterhouseCoopers. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ Tel 029 2066 0820 Fax 029 2023 3741 Email [email protected] Web www.iwa.org.uk www.clickonwales.org ISBN 978 1 904773 64 1 July 2012 CONTENTS chapter 1 Learning from Mondragon ............................................................. 1 JOHN OSMOND chapter 2 A 21st century approach to economic development ......................... 6 ASHLEY DRAKE chapter 3 The Mondragon business development system ............................ 12 ALEX BIRD chapter 4 A new entrepreneurial role for the Wales Co-operative Centre .... 17 DEREK WALKER chapter 5 Extending the co-operative model to public services .......................................................................... 22 MARK DRAKEFORD chapter 6 The -

Download South West TUC Directory

South West TUC Directory The Conservatives want to hand over money meant for injury victims to their fat cat mates in the insurance industry. Millions of workers could lose their right to free or affordable representation if the Tories get their way. Oppose them and tell them to stop Visit www.feedingfatcats.co.uk to take action #FeedingFatCats @feedingfatcats #FeedingFatCats is a campaign run by Thompsons Solicitors. Thompsons is proud to stand up for the injured and mistreated. The Conservatives want to hand over money meant for injury SOUTHWESTTUCDIRECTORY victims to their fat cat mates in Welcome to the South West guide. the insurance industry. TUC Directory. The unions listed Millions of workers could lose their right to free or here represent around half a South West TUC affordable representation if the Tories get their way. million members in the South Church House, Church Road, West, covering every aspect of Filton, Bristol BS34 7BD Oppose them and tell them to stop working life. The agreements t 0117 947 0521 unions reach with employers e [email protected] benefit many thousands more. www.tuc.org.uk/southwest twitter: @swtuc Unions provide a powerful voice Regional Secretary at work, a wide range of services Nigel Costley and a movement for change in e [email protected] these hard times of austerity and cut backs. Southern, Eastern and South West Education Officer Unions champion equal Marie Hughes opportunities, promote learning e [email protected] and engage with partners to Secretary develop a sustainable economy Tanya Parker for the South West. -

Transforming Children and Young People's Mental Health Provision

Unite the Union (in Health) 128 Theobald’s Road, Holborn, London, WC1X 8TN T: 020 7611 2500 | E: [email protected] Unite the union response to: Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper This response is submitted by Unite in Health. Unite is the UK’s largest trade union with 1.5 million members across the private and public sectors. The union’s members work in a range of industries including manufacturing, financial services, print, media, construction, transport, local government, education, health and not for profit sectors. Unite represents in excess of 100,000 health sector workers. This includes eight professional associations - British Veterinary Union (BVU), College of Health Care Chaplains (CHCC), Community Practitioners’ and Health Visitors’ Association (CPHVA), Guild of Healthcare Pharmacists (GHP), Hospital Physicists Association (HPA), Doctors in Unite (formerly MPU), Mental Health Nurses Association (MNHA), Society of Sexual Health Advisors (SSHA). Unite also represents members in occupations such as nursing, allied health professions, healthcare science, applied psychology, counselling and psychotherapy, dental professions, audiology, optometry, building trades, estates, craft and maintenance, administration, ICT, support services and ambulance services. Len McCluskey www.unitetheunion.org General Secretary 2 1. Some key points contained in our response 1.1. The Green Paper is nowhere near bold enough to address the burning injustice of children and young people’s mental ill health (2.3) 1.2. The Green Paper consultation process is totally inadequate (2.4) 1.3. A revised Green Paper should commit to initiating a School Nurse Implementation Plan, similar to the previous ‘Health Visitor Implementation Plan’ (4.3) 1.4.