Spain and Peace-Building in Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Hoax” That Wasn't: the July 23 Qana Ambulance Attack

December 2006 number 1 The “Hoax” That Wasn’t: The July 23 Qana Ambulance Attack Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Claims of a Hoax ......................................................................................................2 The Hoax that wasn’t: Human Rights Watch’s in-depth investigation.......................7 Anatomy of an Attack .............................................................................................. 8 Refuting ‘Evidence’ of the ‘Hoax’ ............................................................................21 Introduction During the Israel-Hezbollah war, Israel was accused by Human Rights Watch and numerous local and international media outlets of attacking two Lebanese Red Cross ambulances in Qana on July 23, 2006. Following these accusations, some websites claimed that the attack on the ambulances “never happened” and was a Hezbollah- orchestrated “hoax,” a charge picked up by conservative commentators such as Oliver North. These claims attracted renewed attention when the Australian foreign minister stated that “it is beyond serious dispute that this episode has all the makings of a hoax.” In response, Human Rights Watch researchers carried out a more in-depth investigation of the Qana ambulance attacks. Our investigation involved detailed interviews with four of the six ambulance staff and the three wounded people in the ambulance, on-site visits to the Tibnine and Tyre Red Cross offices from which the -

3Ws Mapping: January - December 2018

Livelihoods Sector 3Ws Mapping: January - December 2018 MSME/Cooperatives Support Job creation through investment in and Value Chains infrastructures and assets Number of Partners: 1 - 2 3 - 4 5 - 6 Aabboudiye Tall Bire Cheikhlar Aamayer Tall Meaayan Tall Kiri Kouachra 7 - 9 Baghdadi Tall Aabbas Ech-Charqi Ghazayle Tleil Biret Aakkar Qleiaat Aakkar Hayssa Khirbet Daoud Aakkar Tall Aabbas El-Gharbi Rihaniyet Aakkar Khirbet Char Rmoul Berbara Aakkar Qaabrine Khreibet Ej-Jindi Knisse 10 - 11 Mqaiteaa HalbaKroum El-AarabSouaisset Aakkar Machha Jdidet Ej-Joumeh Qoubber Chamra Cheikh Taba Aamaret Aakkar Zouarib Deir Dalloum Qantarat Aakkar Aain Yaaqoub Zouq El Hosniye Tikrit Ouadi El-Jamous Bezbina Bqerzla Mhammaret Bebnine Majdala Hmaire Aakkar Zouq Bhannine berqayel Minie Merkebta Fnaydeq Nabi Youcheaa Jdeidet El-Qaitaa Hrar Mina N 3 Beddaoui Mina N 2 Mina Jardin Trablous Et-Tell Michmich Aakkar TrablousTrablous El-Haddadine, jardins El-Hadid, El-Mharta Btermaz Hermel Miriata Trablous Ez-Zeitoun Bakhaaoun tarane Zgharta Qalamoun Bkeftine Sir Ed-Danniye Dedde Enfe Bqaa Sefrine Ras Baalbek El Gharbi Dar Chmizzine Batroun Bcharre Fekehe Aain Baalbek Aaynata Baalbek Laboue Aarsal -

U.S. Department of State

1998 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices -- Lebanon Page 1 of 10 The State Department web site below is a permanent electro information released prior to January 20, 2001. Please see w material released since President George W. Bush took offic This site is not updated so external links may no longer func us with any questions about finding information. NOTE: External links to other Internet sites should not be co endorsement of the views contained therein. U.S. Department of State Lebanon Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 1998 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, February 26, 1999. LEBANON Lebanon is a parliamentary republic in which the President is by tradition a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, and the Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies a Shiâa Muslim. The Parliament consists of 128 deputies, equally divided between Christian and Muslim representatives. In October Parliament chose a new president, Emile Lahoud, in an election heavily influenced by Syria. He took office in November. The judiciary is independent in principle but is subject to political pressure. Non-Lebanese military forces control much of the country. These include about 25,000 Syrian troops, a contingent of approximately 2,000 Israeli army regulars and 1,500 Israeli-supported militia in the south, and several armed Palestinian factions located in camps and subject to restrictions on their movements. All undermine the authority of the central Government and prevent the application of law in the patchwork of areas not under the Governmentâs control. In 1991 the governments of Syria and Lebanon concluded a security agreement that provided a framework for security cooperation between their armed forces. -

Interim Report on Humanitarian Response

INTERIM REPORT Humanitarian Response in Lebanon 12 July to 30 August 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. THE LEBANON CRISIS AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE ............................................... 1 2.1 NATURE OF THE CRISIS...................................................................................................... 1 2.2 THE INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE DURING THE WAR............................................................. 1 2.3 THE RESPONSE AFTER THE CESSATION OF HOSTILITIES ..................................................... 3 2.4 ORGANISATION OF THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE ............................................................. 3 2.5 EARLY RECOVERY ............................................................................................................. 5 2.6 OBSTACLES TO RECOVERY ................................................................................................ 5 3. HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE IN NUMBERS (12 JULY – 30 AUGUST) ................................... 6 3.1 FOOD ................................................................................................................................6 3.2 SHELTER AND NON FOOD ITEMS......................................................................................... 6 3.3 HEALTH............................................................................................................................. 7 3.4 WATER AND -

MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES in LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon

Inter-Agency MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES IN LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon Calculation of the Most Vulnerable Localities is based on 251 Most Vulnerable Cadastres the following datasets: 87% Refugees 67% Deprived Lebanese 1 - Multi-Deprivation Index (MDI) The MDI is a composite index, based on deprivation level scoring of households in five critical dimensions: i - Access to Health services; Qleiaat Aakkar Kouachra ii - Income levels; Tall Meaayan Tall Kiri Khirbet Daoud Aakkar iii - Access to Education services; Tall Aabbas El-Gharbi Biret Aakkar Minyara Aakkar El-Aatiqa Halba iv - Access to Water and Sanitation services; Dayret Nahr El-Kabir Chir Hmairine ! v - Housing conditions; Cheikh Taba Machta Hammoud Deir Dalloum Khreibet Ej-Jindi ! Aamayer Qoubber Chamra ! ! MDI is from CAS, UNDP and MoSA Living Conditions and House- ! Mazraat En-Nahriyé Ouadi El-Jamous ! ! ! ! ! hold Budget Survey conducted in 2004. Bebnine ! Akkar Mhammaret ! ! ! ! Zouq Bhannine ! Aandqet ! ! ! Machha 2 - Lebanese population dataset Deir Aammar Minie ! ! Mazareaa Jabal Akroum ! Beddaoui ! ! Tikrit Qbaiyat Aakkar ! Rahbé Mejdlaiya Zgharta ! Lebanese population data is based on CDR 2002 Trablous Ez-Zeitoun berqayel ! Fnaydeq ! Jdeidet El-Qaitaa Hrar ! Michmich Aakkar ! ! Miriata Hermel Mina Jardin ! Qaa Baalbek Trablous jardins Kfar Habou Bakhaaoun ! Zgharta Aassoun ! Ras Masqa ! Izal Sir Ed-Danniyé The refugee population includes all registered Syrian refugees, PRL Qalamoun Deddé Enfé ! and PRS. Syrian refugee data is based on UNHCR registration Miziara -

Preliminary Assessment Waste Management

Executive Summary 1 The purpose of this report is to make a preliminary assessment of green jobs potentials in the waste management sector in Lebanon, including solid waste management, hazardous waste management and wastewater treatment. This report provides an overview of waste management in Lebanon, considers potentials for greening the sector, and estimates current and future green jobs in waste management. The current state of the waste management sector in Lebanon is far from ideal. Collection activities are fairly advanced when it comes to municipal solid waste, but insufficient for wastewater, and totally lacking for hazardous waste. Currently only two-thirds of the total generated solid waste undergoes some form of treatment, while the remainder is discarded in open dumpsites or directly into nature. Moreover, wastewater treatment is insufficient and Lebanon currently lacks any effective strategy or system for dealing with most hazardous waste. Incrementally, the sector is nonetheless changing. In recent years green activities such as sorting, composting and recycling have become more common, advanced medical waste treatment is being developed, and several international organisations, NGOs and private enterprises have launched initiatives to green the sector and reduce its environmental impact. Also large-scale governmental initiatives to close down and rehabilitate dumpsites and construct new waste management facilities and wastewater treatment plants are currently being planned or implemented, which will have a considerable impact in greening the waste management sector in Lebanon. In this report, green jobs in waste management are defined as jobs providing decent work that seek to decrease waste loads and the use of virgin resources through reuse, recycling and recovery, and reduce the environmental impact of the waste sector by containing or treating substances that are harmful to the natural environment and public health. -

Short Paper ART GOLD#35B141

ART GOLD LEBANON PROGRAMME PRESENTATION Over 80% of the Lebanese population currently lives in urbanized areas of the country, out of its estimated population of four million people. Lebanon enjoys a diverse and multi cultural society; but is a country characterized by marginalization of its peripheral areas, mainly Akkar in the North, Bekaa in the East, and South Lebanon. The South Lebanon marginalization was often exacerbated by the long-lasting occupations and wars. UNDP ART GOLD Lebanon is being implemented in the four neediest areas where the scores of poverty rates mount high, the socio-economic problems are enormous, and the convergence between deprivation and the effects of the July 2006 war took place. The ART GOLD Lebanon main aim however is to support the Lebanese national government and local communities in achieving the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon utilizes the Local Development methodology, which relies upon the territorial networks and partnerships, which are extremely poor in the Lebanese target areas. To this end, the first steps of the programme aimed at building and strengthening the Relational and Social Capitals of the target territories. Establishing 297 Municipal, 4 Regional Working Groups (RWGs) and 22 Regional Thematic Working Groups. At the same time, regional planning exercises started in the selected sectors. The RWG requested trainings on participatory Strategic Planning, and UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon will provide it within the forthcoming months. Governance, Local Economic Development, Social Welfare, Health, Environment, Gender Equity and Education are the UNDP ART GOLD main fields of interventions at local and national levels. To support the Regional Working Groups efforts, UNDP ARTGOLD Lebanon facilitated the set-up of a number of decentralized cooperation partnerships between Lebanese and European communities. -

A/62/883–S/2008/399 General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/62/883–S/2008/399 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 June 2008 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-second session Sixty-third year Agenda item 17 The situation in the Middle East Identical letters dated 17 June 2008 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to forward herewith the Lebanese Government’s position paper on the implementation of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) (see annex). Also forwarded herewith are the lists of Israeli air, maritime and land violations of the blue line as compiled by the Lebanese armed forces and covering the period between 11 February and 29 May 2008 (see enclosure). I kindly request that the present letter and its annex be circulated as a document of the sixty-second session of the General Assembly under agenda item 17 and as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Caroline Ziade Chargé d’affaires, a.i. 08-39392 (E) 250608 *0839392* A/62/883 S/2008/399 Annex to the identical letters dated 17 June 2008 from the Chargé d’affaires a.i. of the Permanent Mission of Lebanon to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Lebanese Government position paper on the implementation of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006) 17 June 2008 On the eve of the second anniversary of the adoption of Security Council resolution 1701 (2006), and in anticipation of the periodic review of the Secretary-General’s report on the implementation of the resolution, the Lebanese position on the outstanding key elements is as follows: 1. -

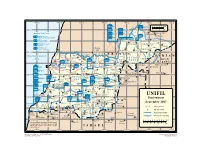

Naqoura, 3 August 2006 PRESS RELEASE Heavy Exchanges of Fire

UNITED NATIONS INTERIM FORCE IN LEBANON (UNIFIL) Naqoura, 3 August 2006 PRESS RELEASE Heavy exchanges of fire continued unabated throughout the UNIFIL area of operation in the past 24 hours. Hezbollah fired the largest number of rockets within a 24-hour period since the outbreak of hostilities from various locations. The IDF continued intensive shelling and aerial bombardment all across the south. It was reported that the IDF made two new ground incursions, entering Lebanese territory in two locations. Yesterday afternoon, they entered again the general area of Marwahin and Ramyah in the western sector. Additional reinforcements were brought in during the night. Heavy shelling and intensive exchanges on the ground are reported this morning from the area of Al Duhayra, west of Marwahin. Last night, the IDF entered Lebanese territory in the general area of Sarda in the eastern sector. Heavy shelling is reported this morning in the area, but no fighting on the ground. The IDF has maintained their presence in five other locations on Lebanese territory, in the general areas of Ayta Ash Shab in the western sector, and Marun Al Ras, Mays Al Jabal, Hula/Markaba, and Kafr Kila/Tayyabah/Addaisseh in the central sector. Intensive shelling is reported in all these areas, except in Marun Al Ras. Sporadic exchanges on the ground were reported in the general area of Tayyabah, Dier Mimess, Hula, and Ayta Ash Shab. The IDF reinforced their presence in the area of Marun Al Ras last night. One rocket from the Hezbollah side impacted directly on a UNIFIL position in the general area of Hula yesterday evening, causing extensive material damage, but no casualties. -

The Hydropolitical Baseline of the Upper Jordan River

"# ! #$"%!&# '& %!!&! !"#$ %& ' ( ) *$ +,-*.+ / %&0 ! "# " ! "# "" $%%&!' "# "( %! ") "* !"+ "# ! ", ( %%&! "- (" %&!"- (( . -

4144R18E UNIFIL Sep07.Ai

700000E 710000E 720000E 730000E 740000E 750000E 760000E HQ East 0 1 2 3 4 5 km ni MALAYSIA ta 3700000N HQ SPAIN IRELAND i 7-4 0 1 2 3 mi 3700000N L 4-23 Harat al Hart Maritime Task Force POLAND FINLAND Hasbayya GERMANY - 5 vessels 7-3 4-2 HQ INDIA Shwayya (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats, 2 auxiliaries) CHINA 4-23 GREECE - 2 vessels Marjayoun 7-2 Hebbariye (1 frigate, 1 patrol boat) Ibil 4-1 4-7A NETHERLANDS - 1 vessel as Saqy Kafr Hammam 4-7 ( ) 1 frigate 4-14 Shaba 4-14 4-13 TURKEY - 3 vessels Zawtar 4-7C (1 frigate, 2 patrol boats) Kafr Shuba ash Al Qulayah 4-30 3690000N Sharqiyat Al Khiyam Halta 3690000N tan LEBANON KHIAM Tayr Li i (OGL) 4-31 Mediterranean 9-66 4-34 SYRIAN l Falsayh SECTOR a s Bastra s Arab Sea Shabriha Shhur QRF (+) Kafr A Tura HQ HQ INDONESIA EAST l- Mine Action a HQ KOREA Kila 4-28 i Republic Coordination d 2-5 Frun a Cell (MACC) Barish 7-1 9-15 Metulla Marrakah 9-10 Al Ghajar W Majdal Shams HQ ITALY-1 At Tayyabah 9-64 HQ UNIFIL Mughr Shaba Sur 2-1 9-1 Qabrikha (Tyre) Yahun Addaisseh Misgav Am LOG POLAND Tayr Tulin 9-63 Dan Jwayya Zibna 8-18 Khirbat Markaba Kefar Gil'adi Mas'adah 3680000N COMP FRANCE Ar Rashidiyah 3680000N Ayn Bal Kafr Silm Majdal MAR HaGosherim Dafna TURKEY SECTOR Dunin BELGIUM & Silm Margaliyyot MP TANZANIA Qana HQ LUXEMBURG 2-4 Dayr WEST HQ NEPAL 8-33 Qanun HQ West BELGIUM Qiryat Shemona INDIA Houla 8-32 Shaqra 8-31 Manara Al Qulaylah CHINA 6-43 Tibnin 8-32A ITALY HQ ITALY-2 Al Hinniyah 6-5 6-16 8-30 5-10 6-40 Brashit HQ OGL Kafra Haris Mays al Jabal Al Mansuri 2-2 1-26 Haddathah HQ FRANCE 8-34 2-31 -

Syria Refugee Response ±

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON South and El Nabatieh Governorates D i s t ri b u t i o n o f t h e R e g i s t e r e d S y r i a n R e f u g e e s a t C a d a s t r a l L e v e l As of 30 June 2017 Baabda SOUTH AND EL NABATIEH Total No. of Household Registered 26,414 Total No. of Individuals Registered 119,808 Aley Mount Lebanon Chouf West Bekaa Midane Jezzine 15 Bhannine Harf Jezzine Ghabbatiye 7 Saida El-Oustani Mazraat El-MathaneBisri 8 Benouati Jezzine Bramiye Bqosta 12 143 Taaid 37 198 573 Qtale Jezzine 9 AAbra Saida Anane 3 Btedine El-Leqch Aaray Hlaliye Saida Karkha Anane Bebé 67 Saida El-Qadimeh 1,215 Salhiyet Saida 74 Aazour 19 748 64 74 11,217 121 67 SabbahBkassine Bekaa Haret Saida Majdelyoun 23 23 Choualiq Jezzine Kfar Falous Sfaray 1,158 354 6 29 Homsiye Wadi Jezzine Saida Ed-Dekermane 49 Lebaa Kfar Jarra Mrah El-Hbasse Roum 27 11 3 Aain Ed-Delb 275 122 12 89 Qabaa Jezzine Miye ou Miyé 334 Qaytoule 2,345 Qraiyet Saida Jensnaya A'ain El-Mir (El Establ) 5 Darb Es-Sim 192 89 67 397 Rimat Deir El Qattine Zaghdraiya Mharbiye Jezzine 83 Ouadi El-Laymoun Maknounet Jezzine 702 Rachaya Maghdouche Dahr Ed-Deir Hidab Tanbourit Mjaydel Jezzine Hassaniye Haytoule Berti Haytoura 651 Saydoun 104 25 13 4 4 Mtayriye Sanaya Zhilta Sfenta Ghaziye Kfar Hatta Saida Roummanet 4,232 Qennarit Zeita 619 Kfar Melki Saida Bouslaya Jabal Toura 126 56 Aanqoun 724 618 Kfar Beit 26 Jezzine Mazraat El-Houssainiye Aaqtanit Kfar Chellal Jbaa En-NabatiyehMazraat Er-Rouhbane 184 Aarab Tabbaya 404 Maamriye 6 Kfar Houne Bnaafoul 4 Jernaya 133 93 Najjariye 187